Mitral regurgitation

Pathophysiology of mitral regurgitation

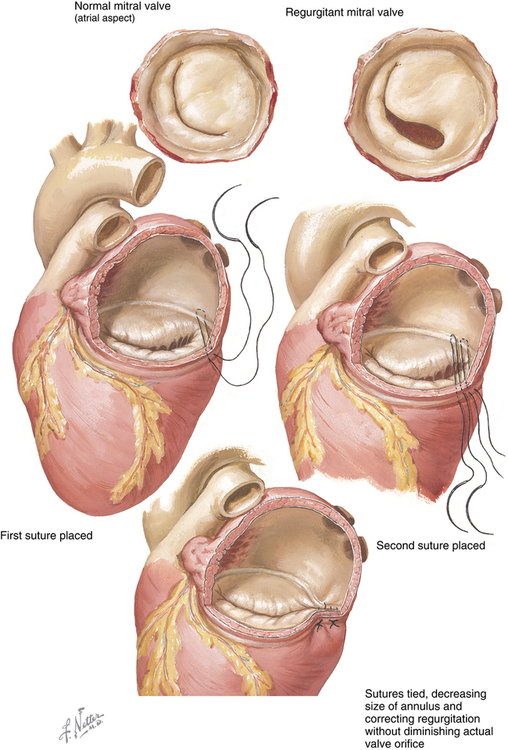

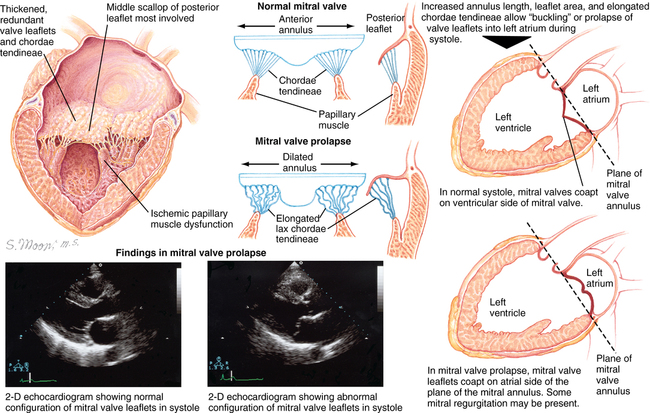

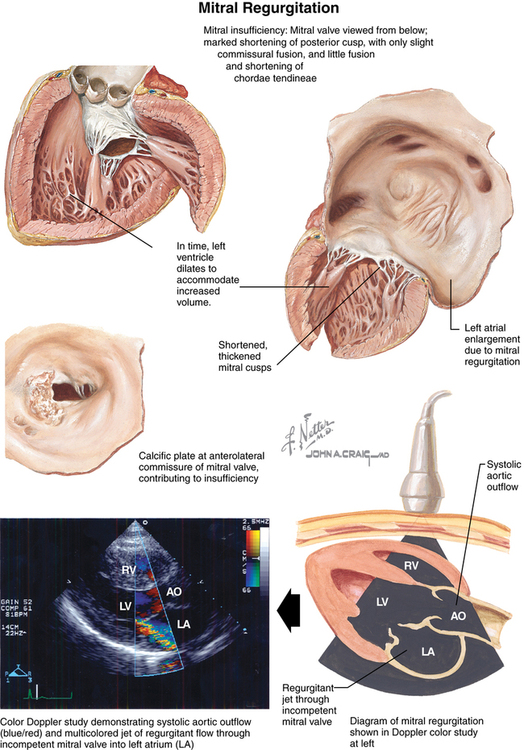

Incompetence of the mitral valve with regurgitation of blood from the left ventricle (LV) into the left atrium (LA) during systole is common (Figure 150-1). Although MR has a number of different causes, in most cases, MR occurs as a result of senescence of the mitral leaflets, and its prevalence increases with age. Degenerative MR is second only to calcific aortic stenosis as the most common valvular cardiac disorder in high-income countries. Mitral valve incompetence usually develops over many years, but incompetence of the valve can develop acutely for reasons other than degenerative disease (e.g., rupture of chordae tendineae from ischemic heart disease). Furthermore, acute MR can superimpose on chronic mitral insufficiency. Barlow disease of the mitral valve is another common condition resulting in MR, characterized by myxoid degeneration of the leaflets leading to thickened and redundant leaflets, mitral annular dilation, and chordal elongation.

Acute MR is usually quite symptomatic (Figure 150-2) and requires surgical intervention. However, the management of chronic regurgitation of the mitral valve is controversial; patients who are symptomatic or who have a decreased ejection fraction are at increased risk of developing complications and are usually considered candidates for surgery. Surgical repair or replacement of the valve not only relieves symptoms, but has increasingly been shown to improve long-term outcome, with reductions in morbidity and mortality rates. Patients who have MR and who have a decreased ejection fraction, an increased LV end-diastolic volume (LVEDV; i.e., dilated LV), chronic atrial fibrillation, or pulmonary hypertension have better long-term outcomes when the valve incompetence is surgically corrected earlier in the course of the disease. Increasing evidence indicates that life expectancy is improved in patients with MR who have surgery before the previously mentioned morbidities develop. Fortunately, the success of valve repair (compared with replacement) and the low morbidity and mortality rates associated with surgical intervention favor early elective surgery. In an effort to prevent progression to worsening disease and subsequent increase in morbidity and mortality rates, current efforts focus on identifying patients with asymptomatic mitral valve disease whose long-term outcome may be favorably impacted if their MR is corrected at an early stage.

Natural history of mitral regurgitation

Chronic compensated MR transitions to decompensated chronic MR when the LV begins to dilate to accommodate the LVEDV necessary to accommodate both the LA regurgitant fraction and the stroke volume ejected to the aorta (i.e., the total volume ejected from the LV). As the LV dilates, the myocardiocytes are no longer able to contract adequately to compensate for the volume overload, and stroke volume begins to decrease. The reduced stroke volume decreases cardiac output, and LV end-systolic volume subsequently increases. A vicious cycle ensues: an increase in end-systolic volume in the LV increases LVEDV, LA pressure, and PAOP. As the PAOP increases, alveoli begin to fill with fluid, leading to the symptoms and signs of pulmonary edema and congestive heart failure. Mild MR is associated with few, if any, complications. However, severe MR may lead to the development of a variety of sequelae (Box 150-1).

Surgical correction of mitral regurgitation

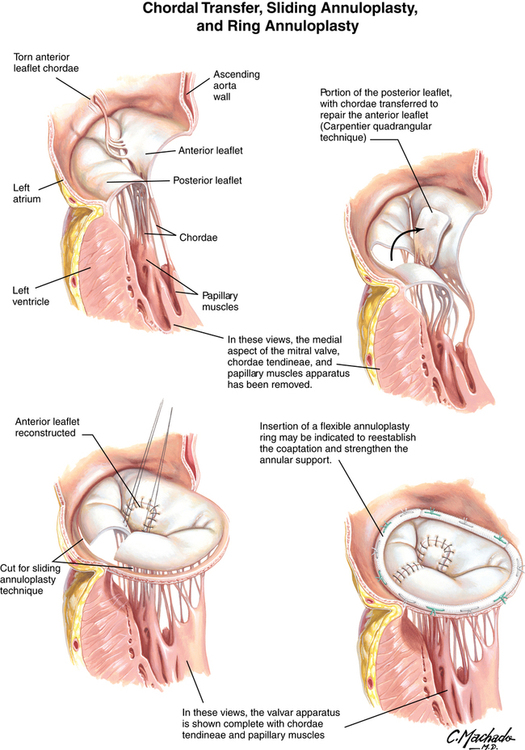

Carpentier revolutionized the treatment of MR when, more than 30 years ago, he published his experience with repairing the mitral valve as opposed to replacing it. His findings, as well as those of others, have led to mitral valve repair being the preferred technique for correcting MR. Approximately 50,000 patients have mitral valve repair annually in the United States. The most common technique to repair the valve is annuloplasty, with or without surgical correction of any defects in the leaflets themselves, or repair of dysfunctional chordae tendineae or reattachment of a ruptured chorda tendinea (Figures 150-3 and 150-4).