Chapter 154 Miscellaneous Uveal Tumors

Epithelial tumors of the ciliary body: congenital

Medulloepithelioma

Medulloepithelioma (diktyoma, teratoneuroma) is a congenital tumor that is generally believed to arise from the epithelium of the medullary tube. This tumor usually arises from the ciliary body epithelium, but medulloepitheliomas of the retina and the optic nerve also occur. The first detailed histologic description of the tumor was by Verhoeff,1 who called it a teratoneuroma, despite the absence of teratomatous features. Fuchs2 reported his observations of a medulloepithelioma and coined the term diktyoma because of the netlike appearance of cells composing the tumor. Grinker3 was the first to use the term “medulloepithelioma,” which has become the preferred name because it refers to the correct cell of origin.

Three large series of medulloepitheliomas have been reported4–6 and provide the bulk of our knowledge of the clinical features of this tumor. In Broughton and Zimmerman’s series,5 the median age at occurrence of initial symptoms was 3.8 years, with a range of 6 months to 41 years. Andersen4 reported that the average age at the time of enucleation was 4.5 years for benign medulloepitheliomas and 7 years for malignant tumors. In the series of Canning et al.6 the median age at diagnosis was 3 years. In all three series, all tumors were unilateral and single, and there was no racial or hereditary predisposition.

The signs and symptoms of the 56 patients reported on by Broughton and Zimmerman5 are summarized in Tables 154.1 and 154.2.

| Clinical finding | Cases (n) |

|---|---|

| Poor vision (or blindness) | 22 |

| Pain | 17 |

| Mass in iris or ciliary body | 10 |

| Leukocoria | 10 |

| Other pupillary abnormality | 2 |

| Exophthalmos (or orbital mass) | 4 |

| Enlarging globe | 4 |

| Strabismus | 3 |

| Epiphora | 2 |

| Change in color of eye | 2 |

| Hyphema | 1 |

(Reproduced with permission from Broughton WL, Zimmerman LE. A clinicopathologic study of 56 cases of intraocular medulloepitheliomas. Am J Ophthalmol 1978;85:407–18.)

Table 154.2 Medulloepithelioma – clinical findings on initial examination

| Clinical finding | Cases (n) |

|---|---|

| Cyst or mass in iris, anterior chamber, or ciliary body | 30 |

| Proptosis or orbital mass | 8 |

| Retinal mass | 2 |

| Glaucoma | 26 |

| Cataract | 14 |

| Buphthalmos | 6 |

| Iritis | 4 |

| Rubeosis | 3 |

| Retinal detachment | 3 |

| Strabismus | 3 |

| Vitreous hemorrhage | 1 |

| Hyphema | 1 |

(Reproduced with permission from Broughton WL, Zimmerman LE. A clinicopathologic study of 56 cases of intraocular medulloepitheliomas. Am J Ophthalmol 1978;85:407–18.)

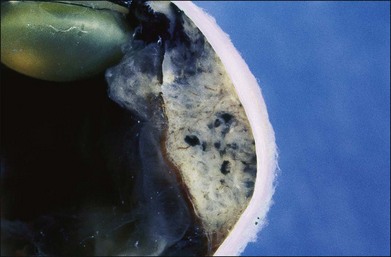

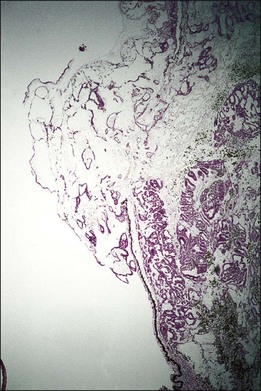

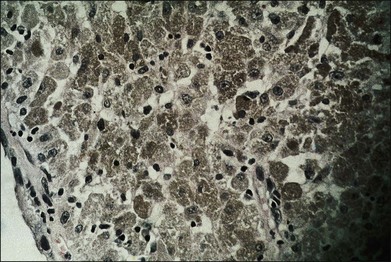

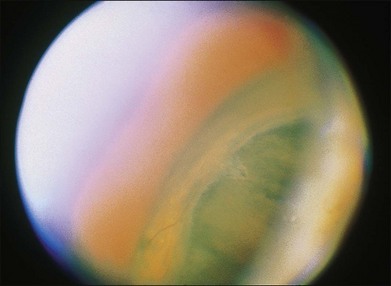

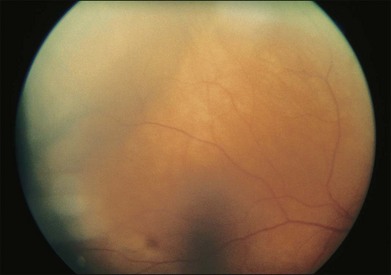

One remarkable feature of medulloepitheliomas is the frequent presence of cysts, which are formed by the production of mucopolysaccharide by the epithelial cells. These cysts can be present within the body of the tumor but also may be free-floating in the anterior or posterior chamber and vitreous (Figs 154.1–154.4). The presence of vitreous or anterior chamber cysts should alert the clinician to consider the possibility of a diagnosis of medulloepithelioma, although vitreous cysts have also been described with malignant melanoma.7

Fig. 154.1 External photograph showing ciliary body mass.

(Case presented by Milton Boniuk, Verhoeff Society, 1997.)

Fig. 154.4 Histopathology demonstrating cystic spaces overlying ciliary body epithelium. (H&E; ×400.)

Another noteworthy feature of medulloepithelioma is that the intraocular pressure is frequently elevated at the time of diagnosis (see Table 154.2). This may result from secondary angle closure by the ciliary body mass, iris neovascularization, or growth of tumor cells across the trabecular meshwork.

Medulloepitheliomas may be benign or malignant. Broughton and Zimmerman5 considered 66% of the tumors in their series to be malignant. Andersen,4 using more stringent criteria, classified 26% of the tumors in his series as malignant. From a practical point of view, even cytologically benign medulloepitheliomas can be locally invasive, extending into the iris, cornea, sclera, or orbit. For that reason all medulloepitheliomas should be considered as potentially malignant tumors, as recommended by Andersen.4

The initial treatment in all reported cases has been surgical – iridectomy, iridocyclectomy, or enucleation – and with total excision, the prognosis is excellent. Canning et al.6 have stressed the importance of attempting local resection (i.e., iridocyclectomy) only in patients with very small tumors. Of the four patients in their series who were treated by iridocyclectomy, all subsequently required enucleation. A total of 45 (80%) of the patients in Broughton and Zimmerman’s series5 treated by iridocyclectomy subsequently required enucleation.

In both Broughton and Zimmerman’s5 and Anderson’s4 series of patients, the most important prognostic factor appeared to be extension of tumor into the orbit. In Broughton and Zimmerman’s series,5 11 patients had extraocular extension; of this group, four died of tumor-related causes. Intracranial spread of tumor was the usual cause of death, although one patient died of lymphatic spread to the mediastinum. The effectiveness of exenteration, radiation therapy, or chemotherapy – used individually or in combination – in managing extraocular extension is not established at this time. Such methods should be considered in cases with extrascleral extension because of the high tumor-related morbidity and mortality in this group of patients.

Glioneuroma

Glioneuromas are choristomatous malformations that arise from the medullary epithelium of the anterior portion of the optic cup. They are extremely rare, and only a few cases have been reported.8–12

These tumors are composed of well-differentiated neural tissue, including neurons and astrocytes. All the reported cases8–12 have eventually required enucleation because of complications of the enlarging tumor or suspected malignancy. Because this is a benign tumor, it could conceivably be managed by local resection.

Astrocytoma

Only two cases of astrocytoma of the ciliary body have been reported.13,14 One patient was 24 years old, and the other was 52 years old. At presentation, both had solid tumors of the ciliary body, and in one patient the astrocytoma was associated with neovascular glaucoma. Growth of the tumor was not documented in either case. These tumors were probably choristomas of the anterior portion of the optic cup. Both lesions consisted of pilocytic astrocytes. Both tumors were treated by iridocyclectomy. Interestingly, in the patient with neovascular glaucoma, the rubeosis was observed to diminish after removal of the tumor.

Epithelial tumors of the ciliary body: acquired

Senile hyperplasia

Senile hyperplasia (Fuchs adenoma) is a benign tumor. The frequency with which it is seen increases with age; this tumor may be observed in approximately 20% of postmortem eyes. Because these tumors are almost always <2 mm in size, they are usually of no clinical significance. However, they may cause a sectorial cataract15 and have been removed because of clinical suspicion of malignancy.15,16

Adenomas and adenocarcinomas

Adenomas and adenocarcinomas have been described by various names, including benign and malignant epitheliomas and adult medulloepitheliomas. Adenomas and adenocarcinomas of the ciliary epithelium appear as solid tumors of the ciliary body. In Andersen’s review of 30 of these cases, the presenting symptom was an observed mass in nine cases and decreased visual acuity in eight cases.4 Other manifestations included glaucoma, cataract, pain, and proptosis. The average age of the patients with adenomas at the time of enucleation was 43 years. For the patients with adenocarcinomas, the average age at the time of enucleation was 55 years. It is noteworthy that several of the reported adenocarcinomas were present in blind eyes involving a previous history of trauma, suggesting that the adenocarcinomas may have represented malignant transformation of reactive hyperplasia of the ciliary epithelium.

The pathologic basis of these tumors has been more thoroughly described elsewhere.7 Briefly, the adenomas consist of cuboidal or columnar cells resembling the nonpigmented or pigmented ciliary epithelium. These cells may have a tubular or papillary arrangement and may be closely packed or enmeshed in a mucoid material.

Because these lesions cannot be reliably differentiated from melanomas, they are usually treated by enucleation or brachytherapy. It is evident that extraocular extension is an important factor in prognosis. Andersen reported two cases of adenocarcinoma that had extended outside the globe at the time of enucleation.4 Both of the patients developed intracranial extension of the tumor. In another series of 21 cases of adenocarcinoma of the ciliary epithelium, follow-up information was available for 16 patients.17 Of those 16 patients, five died of tumor extension into the central nervous system or of widespread metastatic disease; four of the five patients had extraocular extension at the time of initial surgery. The role of exenteration, radiation therapy, or chemotherapy in extraocular extension has not been defined.

Melanocytic tumors

Melanocytoma

The term melanocytoma was first used by Zimmerman and Garron18 to describe a benign pigmented tumor of the optic nerve. Other names that have been used to designate this same lesion include magnocellular nevus and benign melanoma. Melanocytomas of the optic nerve and peripapillary choroid are described in Chapter 136 (Congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium). Therefore only melanocytomas limited to the uvea are discussed here.

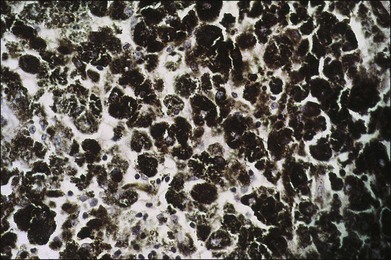

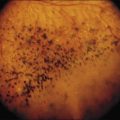

Uveal melanocytomas appear as very darkly pigmented tumors of the choroid, ciliary body, or iris (Fig. 154.5). Although they are probably congenital lesions, the age range at the time of presentation is not sufficiently different from that of malignant melanomas to be useful in differential diagnosis. In a review of ciliary body melanocytomas, Frangieh et al.19 found that most of the reported cases have been in whites. Therefore, unlike optic nerve melanocytomas, uveal melanocytomas do not occur predominantly in blacks. Distinguishing this benign tumor from malignant melanoma is further complicated by the ability of melanocytomas to undergo slow growth. Such slow growth may result in extension of the tumor through the sclera to the episclera. Also, melanocytomas may undergo necrosis, resulting in pigment dispersion, uveitis, and melanomalytic glaucoma. Kathil et al. have described the clinical features of anterior uveal melanocytomas that may be useful in distinguishing melanocytomas in the anterior segment from melanoma.20

Melanocytomas are composed of plump, polyhedral, densely pigmented cells, with small eccentrically placed nuclei that lack prominent nucleoli (Figs 154.6, 154.7). These cells are indistinguishable from the plump, polyhedral cells described by Naumann et al.21 as the exclusive component in approximately 10% of choroidal nevi. Evidence that malignant melanomas may develop from uveal melanocytomas has been provided by cases in which melanomas were present and adjacent to lesions that were indistinguishable from melanocytomas.22–24

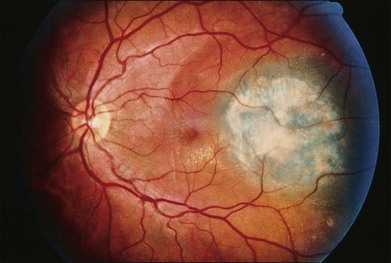

Bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation associated with systemic malignant neoplasms

In 1982 Barr et al.25 described a syndrome characterized by bilateral diffuse melanocytic tumors of the uvea in patients with nonocular malignancy. This condition was originally reported by Machemer26 and has been recently reviewed by Satio et al.27 Gass et al.28 summarized the clinical features of this syndrome, which are: (1) multiple, round or oval, red-to-brown patches at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium in the posterior fundus; (2) a striking fluorescein angiographic pattern of early hyperfluorescence corresponding with these patches; (3) development of multiple, elevated, variably pigmented uveal melanocytic tumors and diffuse thickening of the uveal tract; (4) exudative retinal detachment; and (5) rapid progression of cataract.

Histopathologic study of the uvea in patients with this syndrome has disclosed uveal melanocytic tumors. The cytologic features of the tumors are variable, with most of the cells having benign cytologic features. However, cytologic features of malignancy have been present in several cases,25,29 although no metastatic disease has been documented.

Neurogenic tumors

Neurilemmoma (schwannomas)

Shields et al.30 have reviewed the reported cases of choroidal and ciliary body neurilemmomas. The mean age at the time of diagnosis in the reported cases was 38 years, with a range from 4 to 68 years. Unlike neurofibromas, uveal neurilemmomas are not usually associated with neurofibromatosis. The clinical presentation of these tumors is that of a solid ciliary body or choroidal tumor. Although cytologically benign, they may progressively enlarge at a rate similar to, or greater than, that of choroidal melanomas. In the case studied by Shields et al.30 preoperative ultrasound demonstrated acoustic hollowness, choroidal excavation, and low internal reflectivity. These findings are identical to those of choroidal melanoma. In two subsequently reported cases of anterior uveal neurilemmomas, the tumors were noted to transilluminate brightly.31,32 This may be a helpful clinical finding because it is unusual for anterior uveal melanomas to transilluminate in this way. With increased suspicion, fine needle biopsy and local resection may be considered.

In the case studied by Shields et al.30 there was no clinical or histologic evidence that the tumor was responsive to radiation therapy.

Neurofibroma

Unlike neurilemmomas, uveal neurofibromas are associated with neurofibromatosis. Choroidal neurofibromas are diffuse lesions and appear as diffuse thickening of the choroid, sometimes with an overlying sensory retinal detachment.33

Neurofibromas are nonencapsulated lesions composed of Schwann cells, axons, and fibroblasts. An increase in the number of dendritic uveal melanocytes may be present, simulating congenital melanosis oculi. No treatment is required except to manage vision-threatening complications. (Additional material on neurofibromas may be found in Chapter 134, Remote effects of cancer of the retina.)

Granular cell tumor

The cell type from which granular cell tumors originate is not definitely known; these tumors have features suggestive of a myogenic or neuroectodermal origin. A single case of granular cell tumor, involving the iris and ciliary body of a 24-year-old woman, has been reported.34 The tumor was partially excised, but 1 year after treatment no enlargement of the remaining tumor was reported. Other cases of intraocular granular cell tumor have not been reported.

Myogenic tumors

Leiomyoma

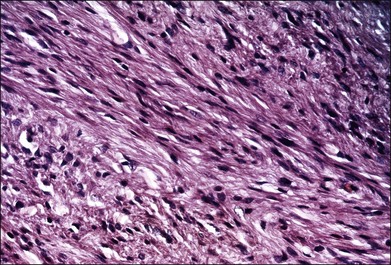

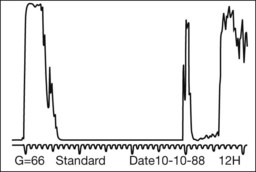

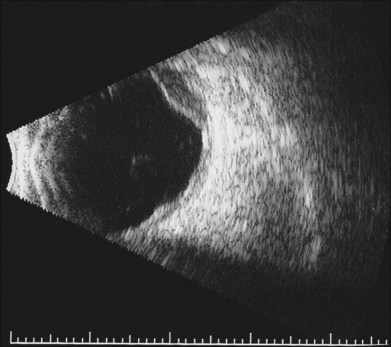

Leiomyomas are rare intraocular tumors that appear as a solid mass of the ciliary body or choroid (Fig. 154.8). As with other solid tumors in these locations, they may cause secondary cataract, glaucoma, and retinal detachment. Leiomyomas arise from the smooth muscle of the ciliary body. In the choroid they probably arise from the smooth muscle or pericytes of the choroidal vessels. They are composed of densely packed, nonpigmented, spindle-shaped cells with oval nuclei (Fig. 154.9). This histologic feature correlates with the very low internal reflectivity seen on A-scan echography of these lesions (Fig. 154.10). It is difficult to differentiate these tumors from amelanotic spindle melanomas solely on the basis of light microscopic features. Immunohistochemical stains and ultrastructural evaluation (Fig. 154.10) are essential in making this distinction.

Clinically, it is very difficult to differentiate leiomyomas from malignant melanomas. As a result, leiomyomas are usually clinically diagnosed and treated as malignant melanomas. A recent report by Shields et al.35 emphasized that leiomyomas of the ciliary body demonstrate increased transillumination. This feature may allow clinical distinction of this tumor from ciliary body melanomas, which generally do not transilluminate in this way. If the diagnosis is established clinically (e.g., by fine-needle biopsy), treatment should consist of managing the secondary complications of this benign tumor.

Mesectodermal leiomyoma

Mesectodermal leiomyoma has been used to describe a benign tumor of the ciliary body that has histologic and ultrastructural features of both smooth muscle and neural tissue (Fig. 154.11).35–37 The peculiar combination of features in this tumor may be explained by the embryologic origin of the ciliary body smooth muscle from the neural crest. The designation mesectodermal leiomyoma should be reserved for tumors that have light or electron microscopic evidence of neurogenic tumors.

Miscellaneous

Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia and lymphoma

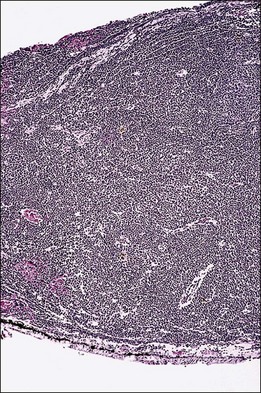

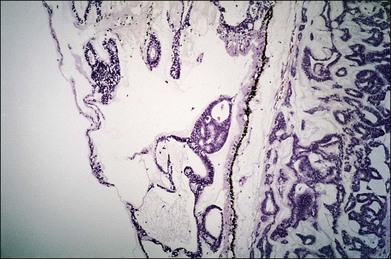

Lymphocytic tumors may involve the eye in a myriad of ways. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia and lymphoma may both present as choroidal tumors (Figs 154.12, 154.13). Choroidal tumors due to lymphocytic infiltration tend to have a more irregular contour to the base of the tumor, and often extend in a more circumferential fashion than is typical of melanocytic or neurogenic tumors of the choroid. In some cases, there will be simultaneous involvement of the orbit or ocular adnexa. Lymphocytic tumors presenting in this fashion can represent isolated extranodal lymphoma (primary uveal lymphoma) or may be present in association with lymphoma at other sites (secondary lymphoma). The diagnosis can be made by incisional biopsy (Fig. 154.14). Patients with lymphoma should undergo staging and treatment appropriate to the type and extent of lymphoma.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma

The iris and ciliary body are usually the sites of intraocular involvement with juvenile xanthogranuloma. However, prominent involvement of the peripapillary choroid, retina, and optic nerve led to enucleation in one case because of the clinical suspicion of a malignant lesion.38

Langerhans cell histiocytosis

Rarely, Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH)39 may present as a choroidal mass lesion without other orbital or systemic involvement.40 LCH is the result of a clonal expansion of Langerhans cells. This monocytic cell type is an antigen presenting cell, and it is unclear why a clonal expansion of this cell type might occur in the choroid. Involvement of the orbit, bones or lungs is much more common.

Hemangiopericytoma

Uveal hemangiopericytoma is an extremely rare neoplasm41–43 The clinical features of these tumors are similar to those of uveal melanomas, including the frequent presence of a sentinel vessel in cases of ciliary body hemangiopericytomas. In one of the reported cases of hemangiopericytoma the magnetic resonance (MR) signal characteristics of the tumor were different from those of choroidal melanomas.15 The authors suggested that MR imaging may provide a mechanism for distinction of this rare tumor from uveal melanoma.

Rhabdomyosarcoma

A remarkable case of rhabdomyosarcoma of the ciliary body in a 12-year-old boy has been reported.44 It is possible that this case represents the one-sided or complete differentiation of a teratoid medulloepithelioma along the line of a rhabdomyosarcoma. At the last reported follow-up examination (2 years after enucleation), the child was alive without evidence of metastasis or local recurrence. Three additional cases of primary rhabdomyosarcoma of the iris have been reported.44–47

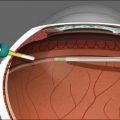

Choroidal biopsy

Given the variety of rare lesions that occur in the uvea, often masquerading as more common clinical entities, it is useful to consider when a biopsy might be considered. The techniques and indications for biopsy have been reported by Lim et al.48 Briefly, biopsy might be considered in anterior uveal tumors, particularly if they fail to block transillumination. Patients with current or past history of systemic diseases that are associated with choroidal tumors should also be considered for biopsy. Ciliary body and/or choroidal biopsy may be performed from an external approach, and choroidal lesions may also be biopsied using vitsectomy techniques. Such biopsies can generally be obtained with minimal morbidity.

1 Verhoeff FH. A rare tumor arising from the pars ciliaris retinae (teratoneuroma) of a nature hitherto unrecognized and its relation to the so-called glioma retinae. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1904;10:351–377.

2 Fuchs E. Wucherungen und Geschwulste des Ziliarepithels. Albrecht von Graefes Arch Klin Exp Ophthalmol. 1908;68:534–558.

3 Grinker RR. Gliomas of the retina, including the results of studies with silver impregnations. Arch Ophthalmol. 1931;5:920–935.

4 Andersen SR. Medulloepithelioma of the retina. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1962;2:483–506.

5 Broughton WL, Zimmerman LE. A clinicopathologic study of 56 cases of intraocular medulloepitheliomas. Am J Ophthalmol. 1978;85:407–418.

6 Canning CR, McCartney AC, Hungerford J. Medulloepithelioma (diktyoma). Br J Ophthalmol. 1988;72:764–767.

7 Green WR. Neuroepithelial tumors of the ciliary body. Ophthalmic pathology: an atlas and textbook. Spencer WH, ed. Ophthalmic pathology: an atlas and textbook. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1985;vol 2.

8 Addison DJ. Glioneuroma of the ciliary body and iris in a 2-year-old girl. Seventh biennial meeting of the Association of Ophthalmic Alumni, Washington, DC, June 1977. Washington DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1977.

9 Kivela T, Kauniskangas L, Miettinen P, et al. Glioneuroma associated with colobomatous dysplasia of the anterior uvea and retina: a case simulating medulloepithelioma. Ophthalmology. 1989;96:1799–1808.

10 Kuhlenbeck H, Haymaker W. Neuroectodermal tumors containing neoplastic neuronal elements: ganglioneuroma, spongioneuroblastoma, and glioneuroma. Mil Surg. 1946;99:273–304.

11 Manz HJ, Rosen DA, Macklin RD, et al. Neuroectodermal tumor of anterior lip of the optic cup: glioneuroma transitional to teratoid medullo-epithelioma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1973;89:382–386.

12 Spencer WH, Jesberg DO. Glioneuroma (choristomatous malformation of the optic cup margin): a report of two cases. Arch Ophthalmol. 1973;89:387–391.

13 Farber MG, Smith ME, Gans LA. Astrocytoma of the ciliary body. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987;105:536–537.

14 Naeser P, Moller P. Astrocytoma of the ciliary body: a clinico-pathological case report. Acta Ophthalmol. 1985;63:28–30.

15 Bateman JB, Foos RY. Coronal adenomas. Arch Ophthalmol. 1979;97:2379–2384.

16 Iliff WJ, Green WR. The incidence and histology of Fuchs’ adenoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1972;88:249–254.

17 Croxatto JO, Zimmerman LE. Malignant nonpigment intraocular tumors of neuroectodermal origin in adults: a review of 21 cases. Pers. comm., April 1981.

18 Zimmerman LE, Garron LK. Melanocytoma of the optic disc. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1962;2:431–440.

19 Frangieh GT, El Baba F, Traboulsi EL, et al. Melanocytoma of the ciliary body: presentation of four cases and review of nineteen reports. Surv Ophthalmol. 1985;29:328–334.

20 Kathil P, Milman T, Finger PT. Characteristics of anterior uveal melanocytomas in 17 cases. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:1874–1880.

21 Naumann G, Yanoff M, Zimmerman LE. Histogenesis of malignant melanomas of the uvea. I. Histopathologic characteristics of nevi of the choroid and ciliary body. Arch Ophthalmol. 1966;76:784–796.

22 Baker-Griffith AE, McDonald PR, Green WR. Malignant melanoma arising in a choroidal magnacellular nevus (melanocytoma). Can J Ophthalmol. 1976;11:140–146.

23 Heitman KF, Kincaid MC, Steahly L. Diffuse malignant change in a ciliochoroidal melanocytoma in a patient of mixed racial background. Retina. 1988;8:67–72.

24 Thomas CI, Purnell EW. Ocular melanocytoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1969;67:79–86.

25 Barr CC, Zimmerman LE, Curtin VT, et al. Bilateral diffuse uveal tumors associated with systemic malignant neoplasms: a recently recognized syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100:249–255.

26 Machemer R. Zur Pathogenese des flachenhaften malignen Melanomas. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 1966;148:641–652.

27 Saito W, Kase S, Yoshida K, et al. Bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation in a patient with cancer-associated retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:942–945.

28 Gass JDM, Gieser RG, Wilkinson CP, et al. Bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation in patients with occult carcinoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108:527–533.

29 Margo CE, Pavan PR, Gendelman D, et al. Bilateral melanocytic uveal tumors associated with systemic nonocular malignancy. Retina. 1987;7:137–141.

30 Shields JA, Sanborn GE, Kurz GH, et al. Benign peripheral nerve tumor of the choroid: a clinicopathologic correlation and review of the literature. Ophthalmology. 1981;88:1322–1329.

31 Hufnagel TJ, Sears ML, Shapiro M, et al. Ciliary body neurilemoma recurring after 15 years. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1988;226:443–446.

32 Smith PA, Damato BE, Ko MK, et al. Anterior uveal neurilemmoma: a rare neoplasm simulating malignant melanoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1987;71:34–40.

33 Shields JA. Diagnosis and management of intraocular tumors. St Louis: Mosby; 1983.

34 Cunha SL, Lobo FG. Granular-cell myoblastoma of the anterior uvea. Br J Ophthalmol. 1966;50:99–101.

35 Shields JA, Shields CL, Eagle RC, Jr. Mesectodermal leiomyoma of the ciliary body managed by partial lamellar iridocyclochoroidectomy. Ophthalmology. 1989;96:1369–1376.

36 Jakobiec FA, Font RL, Tso MOM, et al. Mesectodermal leiomyoma of the ciliary body: a tumor of presumed neural crest origin. Cancer. 1977;39:2102–2113.

37 White V, Stevenson K, Garner A, et al. Mesectodermal leiomyoma of the ciliary body: case report. Br J Ophthalmol. 1989;73:12–18.

38 Wertz FD, Zimmerman LE, McKeown CA, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma of the optic nerve, disc, retina, and choroid. Ophthalmology. 1982;89:1331–1335.

39 Margo CE, Goldman DR. Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53:332–358.

40 Kim Taek, Lee SangMin. Choroidal Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2000;78:97–100.

41 Brown HH, Brodsky MC, Hembree K, et al. Supraciliary hemangiopericytoma. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:378–382.

42 Gieser SC, Hufnagel TJ, Jaros PA, et al. Hemangiopericytoma of the ciliary body. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988;106:1269–1272.

43 Papale JJ, Frederick AR, Albert DM. Intraocular hemangiopericytoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983;101:1409–1411.

44 Wilson ME, McClatchey SK, Zimmerman LE. Rhabdomyosarcoma of the ciliary body. Ophthalmology. 1990;97:1484–1488.

45 Elsas FJ, Mroczek EC, Kelly DR, et al. Primary rhabdomyosarcoma of the iris. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109:982–984.

46 Naumann G, Font RL, Zimmerman LE. Electron microscopic verification of primary rhabdomyosarcoma of the iris. Am J Ophthalmol. 1972;74:110–117.

47 Woyke S, Chwirot R. Rhabdomyosarcoma of the iris. Br J Ophthalmol. 1972;56:60–64.

48 Lim LL, Suhler EB, Rosenbaum JT, et al. The role of choroidal and retinal biopsies in the diagnosis and management of atypical presentations of uveitis. Trans Ann Ophthalmol Soc. 2005;103:84–95.