Miscellaneous Infections Caused by Fungi and Pneumocystis

For many other fungi and for Pneumocystis, the normal host is essentially protected from the organism. Disease occurs almost exclusively as a consequence of an underlying illness or a breakdown of normal defense mechanisms. Aspergillus is perhaps the most important fungus of this sort and is the main one considered in this chapter. Pneumocystis, which has a debatable taxonomic status, is considered both in this chapter and in the discussion of AIDS in Chapter 26. The less common fungi (e.g., Mucor and Candida) and protozoa (e.g., Toxoplasma) affecting the immunosuppressed host are not considered in detail here, but further information can be obtained from the references at the end of this chapter.

Fungal Infections

Aspergillosis

Aspergilloma

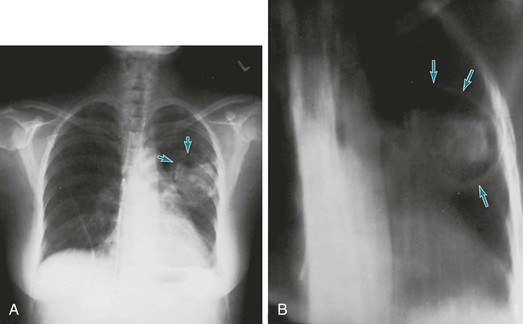

Clinically, patients with an aspergilloma present either with hemoptysis or with no symptoms but suggestive findings on chest radiograph. Classically the radiograph demonstrates an apparent mass in the upper lobes surrounded by a lucent rim, representing air in the cavity around the fungus ball (Fig. 25-1). When the patient changes position, the fungus ball often changes position within the cavity, owing to the effects of gravity.

Pneumocystis Infection

Pneumocystis appears to be widely distributed in nature. It normally can be found in the lungs of a variety of animals as well as in humans. Yet the organisms do not cause disease in normal hosts, only in individuals with significant impairment in host defenses, specifically cellular immunity. The key cell appears to be the helper T lymphocyte CD4+, whose numbers, function, or both can be diminished by specific diseases or immunosuppressive drugs. Before the recognition of AIDS, P. jiroveci pneumonia was seen most commonly in patients with severe malnutrition, malignancy, organ transplantation, or other diseases requiring treatment with corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive agents. However, after the identification of AIDS and before the introduction of ART, the majority of cases were seen in patients with AIDS and greatly reduced numbers of CD4+ lymphocytes. The problem of Pneumocystis pneumonia as it occurs in AIDS is discussed in more detail in Chapter 26.

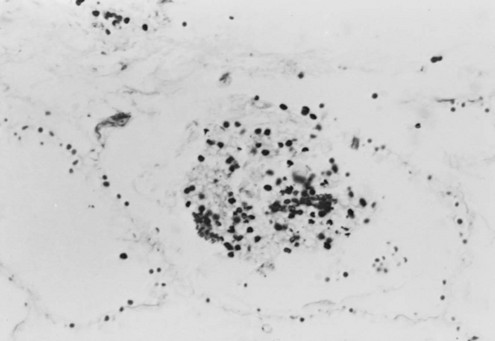

Pneumocystis cysts, which are seen in the lung tissue of infected patients, appear on light-microscopic examination as round or cup-shaped structures. They do not stain well with routine hematoxylin and eosin stain; instead they require special stains such as methenamine silver (Fig. 25-2). The tissue response to the organism seen on microscopic examination of lung tissue includes infiltration of mononuclear cells within the pulmonary interstitium and exudation of foamy fluid (containing cysts) into alveolar spaces. An exuberant host inflammatory response to the organism contributes to the pulmonary injury. As a result, many patients with Pneumocystis pneumonia are treated with corticosteroids in addition to antimicrobial therapy against Pneumocystis early in the course of the disease to suppress this response.

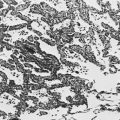

Clinically, Pneumocystis pneumonia usually manifests with dyspnea and fever in immunocompromised patients. Interestingly, in patients for whom treatment with corticosteroids was the risk factor for developing Pneumocystis pneumonia, symptoms frequently develop (and the infection is recognized) as the dose of corticosteroids is being tapered. This observation further supports the concept that the host inflammatory reaction to the organism, which is suppressed by corticosteroids and blossoms only as the steroid dose is being tapered, is responsible for much of the clinical presentation. The chest radiograph commonly shows diffuse bilateral infiltrates, which can have the appearance of either an interstitial or an alveolar filling pattern (Fig. 25-3). Alveolar filling and resultant areas of shunting often make hypoxemia a particularly prominent clinical feature in these patients. Although the disease is often insidious in onset in AIDS patients, it commonly manifests in other immunocompromised patients as a relatively acute-onset pneumonia that, if untreated, can rapidly progress to respiratory failure and death within days.

Fungal Infections (General References)

Chong, S, Lee, KS, Yi, CA, et al. Pulmonary fungal infection: imaging findings in immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients. Eur J Radiol. 2006;59:371–383.

Dismukes, WE. Introduction to antifungal drugs. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:653–657.

Lewis, RE. Current concepts in antifungal pharmacology. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86:805–817.

Limper, AH, Knox, KS, Sarosi, GA, et al. An official American Thoracic Society Statement: treatment of fungal infections in adult pulmonary and critical care patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;183:96–128.

Pagano, L, Caira, M, Fianchi, L. Pulmonary fungal infections with yeasts and Pneumocystis in patients with hematological malignancy. Ann Med. 2005;37:259–269.

Pagano, L, Fianchi, L, Leone, G. Fungal pneumonia due to molds in patients with hematological malignancies. J Chemother. 2006;18:339–352.

Sanchez, A, Larsen, R. Emerging fungal pathogens in pulmonary disease. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2007;13:199–204.

Saubolle, MA. Fungal pneumonias. Semin Respir Infect. 2000;15:162–177.

Yao, Z, Liao, W. Fungal respiratory disease. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2006;12:222–227.

Buck, BE, Malinin, TI, Davis, JH. Transmission of histoplasmosis by organ transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:310.

McLeod, DS, Mortimer, RH, Perry-Keene, DA, et al. Histoplasmosis in Australia: report of 16 cases and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2011;90:61–68.

Wheat, LJ, Freifeld, AG, Kleiman, MB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:807–825.

Wheat, J, Sarosi, G, McKinsey, D, et al. Practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:688–695.

Wood, KL, Hage, CA, Knox, KS, et al. Histoplasmosis after treatment with anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1279–1282.

Galgiani, JN. Coccidioidomycosis: a regional disease of national importance. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:293–300.

Galgiani, JN, Ampel, NM, Blair, JE, et al. Coccidioidomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1217–1223.

Galgiani, JN, Ampel, NM, Catanzaro, A, et al. Practice guidelines for the treatment of coccidioidomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:658–661.

Parish, JM, Blair, JE. Coccidioidomycosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:343–348.

Ruddy, BE, Mayer, AP, Ko, MG, et al. Coccidioidomycosis in African Americans. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86:63–69.

Saubolle, MA, McKellar, PP, Sussland, D. Epidemiologic, clinical and diagnostic aspects of coccidioidomycosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:26–30.

Spinello, IM, Johnson, RH, Baqu, S. Coccidioidomycosis and pregnancy: A review. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2007;1111:358–364.

Chapman, SW, Bradsher, RW Jr, Campbell, GD, Jr., et al. Practice guidelines for the management of patients with blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:679–683.

Chapman, SW, Dismukes, WE, Proia, LA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1801–1812.

Sarosi, GA, Davies, SF. Blastomycosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1979;120:911–938.

Agarwal, R. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Chest. 2009;135:805–826.

Almyroudis, NG, Holland, SM, Segal, BH. Invasive aspergillosis in primary immunodeficiencies. Med Mycol. 2005;43(Suppl 1):S247–S259.

Cockrill, BA, Hales, CA. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Annu Rev Med. 1999;50:303–316.

Herbrecht, R, Denning, DW, Patterson, TF, Invasive Fungal Infections Group of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the Global Aspergillus Study Group. voriconazole versus amphotericin B for primary therapy of invasive aspergillosis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:408–415.

Shibuya, K, Ando, T, Hasegawa, C, et al. Pathophysiology of pulmonary aspergillosis. J Infect Chemother. 2004;10:138–145.

Paterson, DL, Singh, N. Invasive aspergillosis in transplant recipients. Medicine. 1999;78:123–138.

Reichenberger, F, Habicht, JM, Gratwohl, A, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in neutropenic patients. Eur Respir J. 2002;19:743–755.

Segal, BH. Medical progress: aspergillosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1870–1884.

Sharma, OP, Chwogule, R. Many faces of pulmonary aspergillosis. Eur Respir J. 1998;12:705–715.

Soubani, AO, Chandrasekar, PH. The clinical spectrum of pulmonary aspergillosis. Chest. 2002;121:1988–1999.

Stevens, DA, Kan, VL, Judson, MA, et al. Practice guidelines for diseases caused by Aspergillus. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:696–709.

Walsh, TJ, Anaissie, EJ, Denning, DW, et al. Treatment of aspergillosis: clinical practice guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:327–360.

Hughes, WT, Rivera, GK, Schell, MJ, et al. Successful intermittent chemoprophylaxis for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonitis. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1627–1632.

Kovacs, JA, Gill, VJ, Meshnick, S, et al. New insights into transmission, diagnosis, and drug treatment of Pneumocystis carinii/jiroveci pneumonia. JAMA. 2001;286:2450–2460.

Kovacs, JA, Masur, H. Evolving health effects of Pneumocystis: one hundred years of progress in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2009;301:2578–2585.

Pop, SM, Kolls, JK, Steele, C. Pneumocystis: immune recognition and evasion. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:17–22.

Russian, DA, Levine, SJ. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients without HIV infection. Am J Med Sci. 2001;321:56–65.

Thomas, CF, Limper, AH. Current insights into the biology and pathogenesis of Pneumocystis pneumonia. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:298–308.