Meningiomas

MENINGIOMAS

Meningiomas arise from meningothelial (arachnoid) cells in the leptomeninges. These cells have both epithelial and mesenchymal characteristics, which are shown by meningiomas in a spectrum of diverse histologic appearances. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification recognizes several variants of meningioma (Table 43.1). Differentiation towards the epithelial end of the histologic spectrum is represented by the meningothelial and secretory variants. Differentiation towards the mesenchymal end of the spectrum is represented by the fibrous and metaplastic variants.

Table 43.1

WHO classification (2007) of meningiomas

WHO grade 1

Meningothelial

Fibrous (fibroblastic)

Transitional (mixed)

Psammomatous

Angiomatous

Microcystic

Secretory

Lymphoplasmacyte-rich

Metaplastic

WHO grade 2

Atypical

Chordoid

Clear cell

WHO grade 3

Anaplastic

Papillary

Rhabdoid

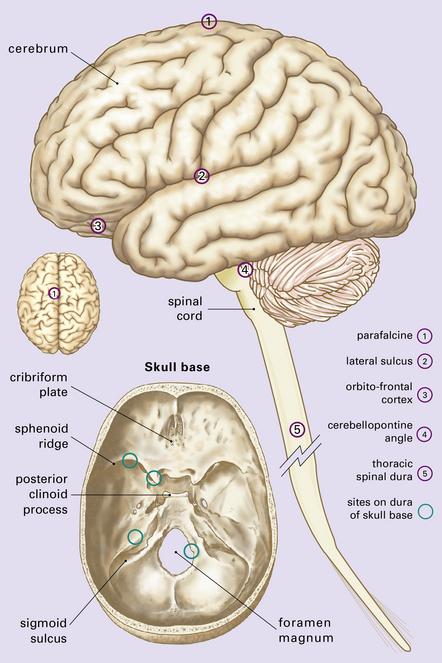

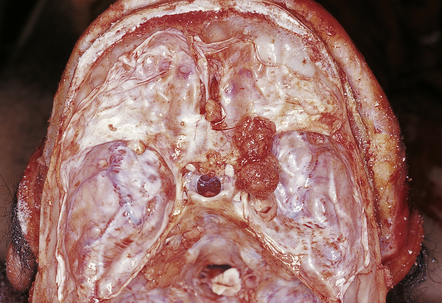

Meningiomas occur throughout the central nervous system (CNS), but have a predilection for certain sites (Fig. 43.1). Unusual sites include the ventricles and the epidural space. Depending on its location, a meningioma can grow for a prolonged period and to a considerable size before producing symptoms and signs. It may lead to increased intracranial pressure, loss of CNS function, or epilepsy. Some meningiomas are incidental post-mortem findings (Fig. 43.2).

43.2 Meningiomas on the sphenoid ridge and olfactory groove.

These meningiomas were an incidental postmortem finding.

Not all meningeal neoplasms are meningiomas. Metastatic neoplasms (see Chapter 46); hemangiopericytomas, hemangioblastomas, melanocytic neoplasms, and various mesenchymal neoplasms (see all in Chapter 45), may be located in the meninges. The term angioblastic meningioma, previously used for angiomatous meningiomas, hemangiopericytomas, and hemangioblastomas, is obsolete. Meningeal hemangiopericytomas/solitary fibrous tumors and hemangioblastomas are morphologically, immunophenotypically, and genetically distinct from meningiomas.

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

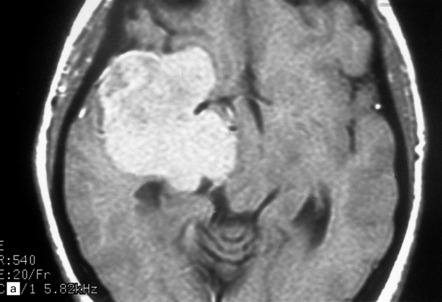

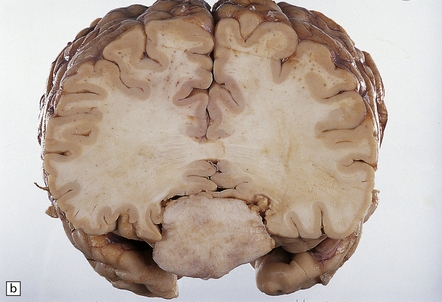

Meningiomas arising around the cerebral convexities are generally spherical because they can displace underlying brain (Fig. 43.3). The shape of other meningiomas is constrained by their location, e.g. optic nerve meningiomas are fusiform. Meningiomas occasionally envelop rather than displace adjacent CNS structures (Fig. 43.4). Some meningiomas, particularly those on the sphenoid ridge, grow as plaques within the dura (en plaque meningioma).

43.3 Meningioma.

(a) A contrast-enhanced MR scan showing a large sphenoid wing meningioma. The even enhancement is typical. (Courtesy of Dr J S Millar, Wessex Neurological Center.) (b) A midline tumor has compressed the inferior part of the frontal lobes.

Most meningiomas have a smooth or slightly lobulated surface and a rubbery consistency (Fig. 43.5). They are usually solid on sectioning, but may have a soft, granular texture, and there may be obvious interlacing bands of fibrous tissue. Rarer variants may have specific macroscopic features, e.g. the microcystic meningioma has a gelatinous texture and the psammomatous meningioma feels gritty.

43.5 Formalin-fixed meningiomas.

(a) The tumor has a lobular appearance. Note the entrapped dura. (b) In this pediatric case, meningioma encircles optic nerve.

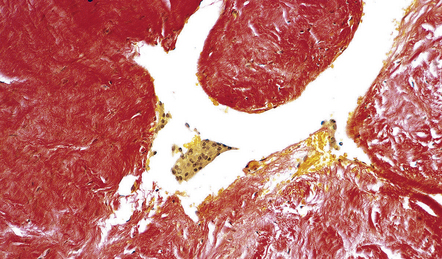

The attached dura should be inspected for separate nodules of tumor, and the relationship between dura and tumor should be examined histologically (Fig. 43.6). Invasion of adjacent bone may be evident at operation, and pieces of bone may be submitted for examination (Fig. 43.7). The infiltrated bone often shows hyperostosis, a feature that can, however, occur adjacent to meningiomas even in the absence of bony invasion.

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

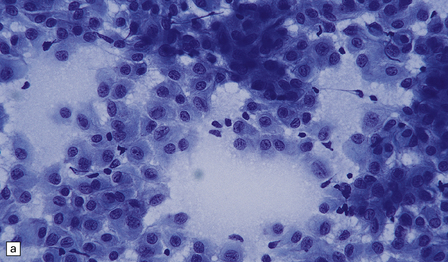

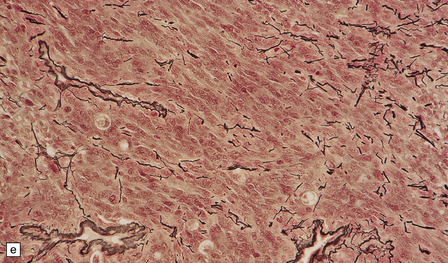

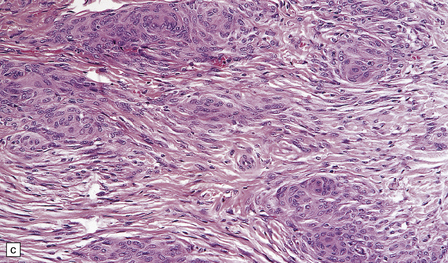

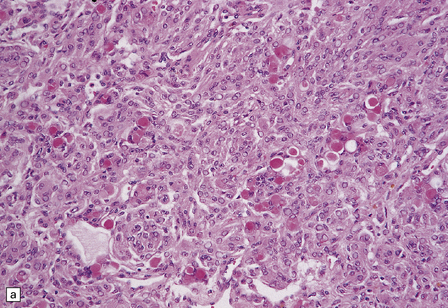

Meningothelial meningiomas consist of sheets or lobules of oval cells that form rudimentary meningothelial whorls in a few places. Cytologic borders are indistinct. Single small nucleoli and nuclear pseudoinclusions formed by invaginations of the nuclear membrane are common (Fig. 43.8).

43.8 Meningothelial meningioma.

(a) Oval cells with prominent small nucleoli characterize the cytology of this meningothelial meningioma in a smear preparation. (b) Typical meningothelial meningioma containing a sheet of cells with indistinct borders and nuclear pseudo-inclusions. (c) Rudimentary whorls in a meningothelial meningioma. (d) This tumor has infiltrated the fibrous capsule of the optic nerve. (e) Meningothelial meningioma with sparse reticulin.

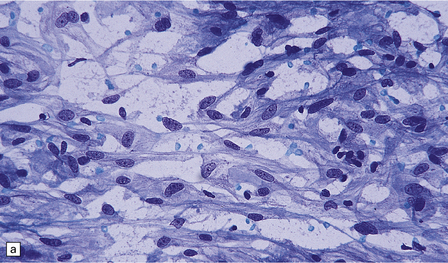

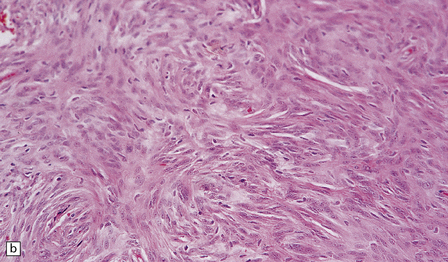

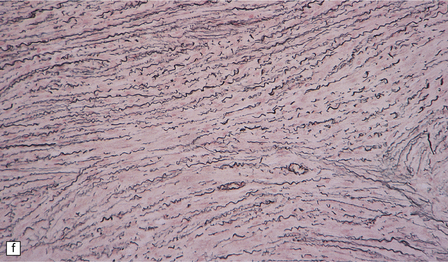

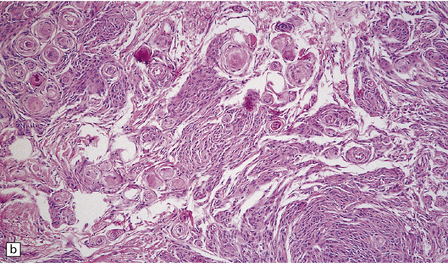

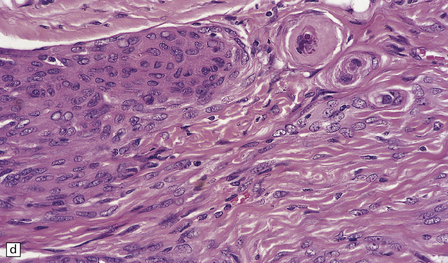

Fibrous meningiomas consist of spindle-shaped cells associated with variable amounts of pericellular collagen (Fig. 43.9).

43.9 Fibrous meningioma.

(a) A smear preparation of this meningioma consists of elongated cells, many of which contain a single nucleolus. (b) This is the tumor from which the smear in (a) was prepared. (c) Spindle cells in a fibrous meningioma. (d) Abundant collagen in one region of a fibrous meningioma. (e) This tumor is characterized by fibrous nodules. (f) Fibrous meningiomas contain more reticulin than do other variants, but not around every cell.

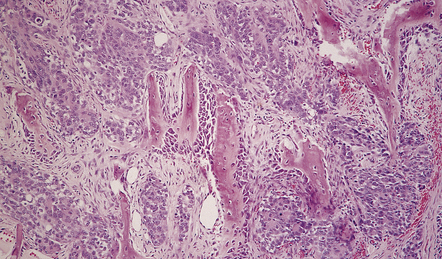

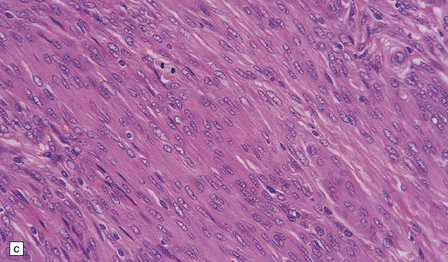

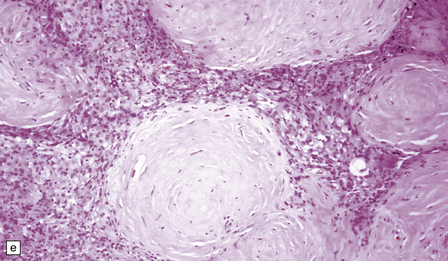

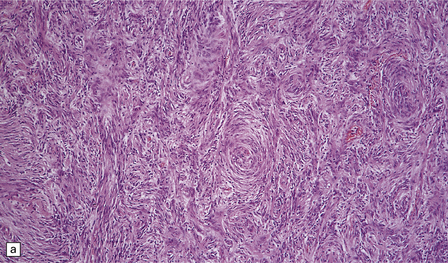

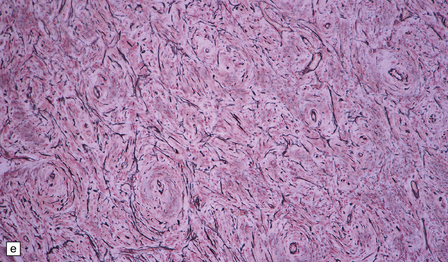

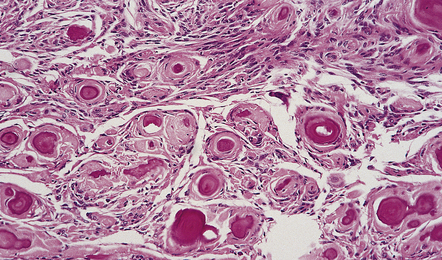

Meningothelial and fibrous areas are combined in transitional meningiomas, which also contain widespread whorls and scattered psammoma bodies (Fig. 43.10).

43.10 Transitional meningioma.

(a) This typical example is composed of whorls and cords of neoplastic cells. (b) This contains prominent whorls and psammoma bodies. (c) Note the combination of whorling and fascicular patterns. (d) This field also shows a juxtaposition of meningothelial and fibrous areas. (e) Strands of reticulin in a transitional meningioma.

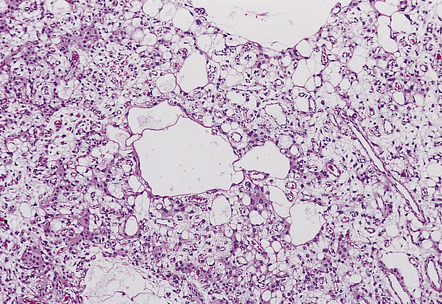

Foci of foamy (xanthomatous) cells are frequently found in meningiomas (Fig. 43.11), and should not be mistaken for micronecrosis.

Other variants of meningioma (Table 43.2) have distinctive architectural and cytologic features which are usually combined with the prototypical histology described above (Figs 43.12–43.17).

Table 43.2

Characteristics of variants of classic (WHO grade 1) meningiomas

Psammomatous

A transitional meningioma with many psammoma bodies

Intraspinal, orbital, and olfactory groove meningiomas are often psammomatous

Angiomatous

Multiple blood vessels of varying size among groups of meningothelial cells

Vessels tend to have thickened, hyaline walls

Intervening neoplastic cells show moderate nuclear pleomorphism

Microcystic

Cytoplasmic processes separated by extracellular fluid to produce a lacy meshwork of microcysts

Groups of thick-walled blood vessels and foamy cells

Moderate nuclear pleomorphism

Sparse whorls and psammoma bodies

Secretory

PAS-positive globular inclusions within intracytoplasmic lumina lined by microvilli The microvilli are not usually discernible except by electron microscopy

Surrounding cells are immunoreactive for cytokeratins

Lymphoplasmacyte-rich

Abundant lymphocytes and plasma cells appear as an inflammatory infiltrate

May show germinal centers

May occupy a spectrum with chordoid variant

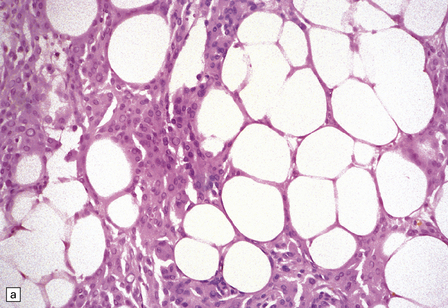

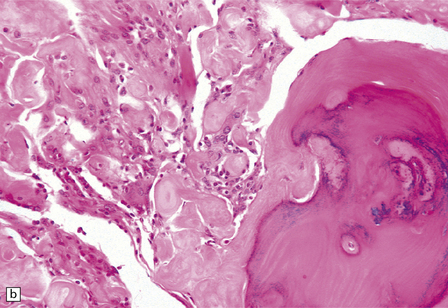

Metaplastic

Mesenchymal differentiation (i.e. lipomatous, cartilaginous, osseous)

43.12 Psammomatous meningioma.

This consists of numerous compact whorls that contain psammoma bodies.

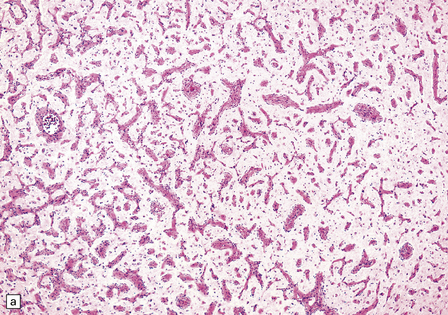

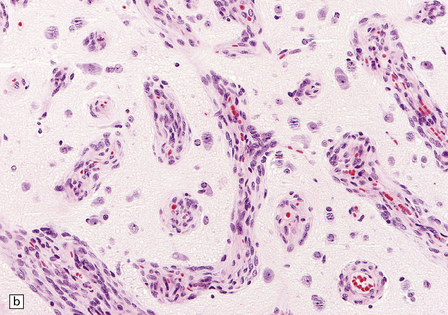

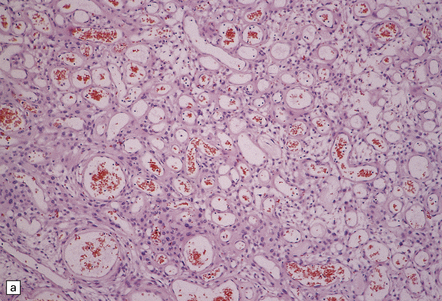

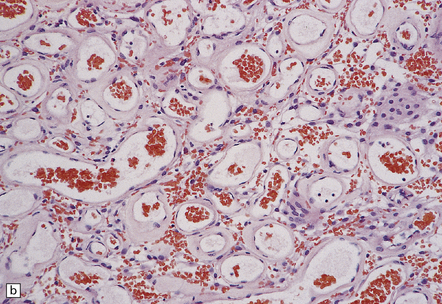

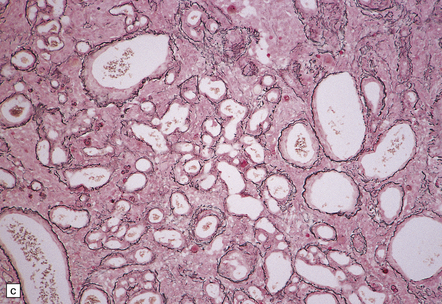

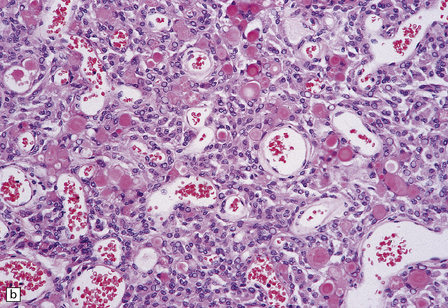

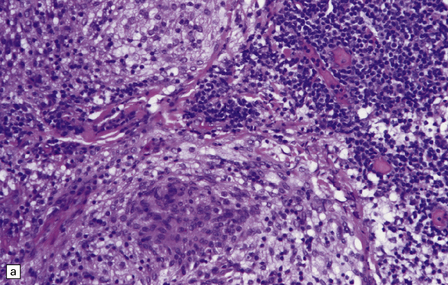

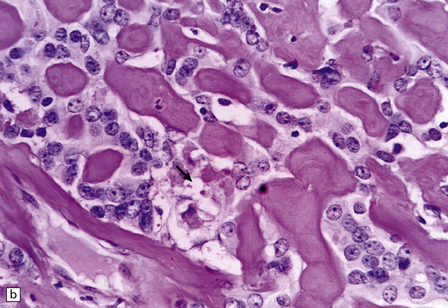

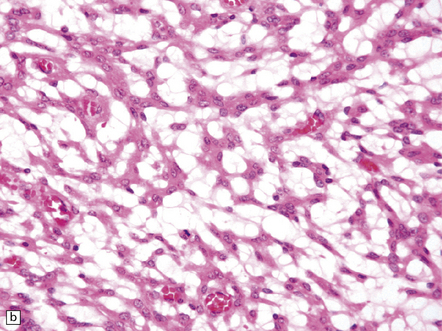

43.13 Angiomatous meningioma.

(a) Blood vessels are strikingly prominent. (b) Groups of neoplastic cells lie between thick-walled vessels. (c) A reticulin preparation highlights the numerous blood vessels.

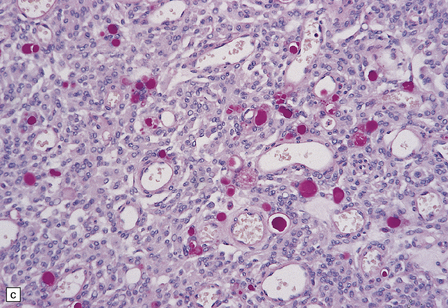

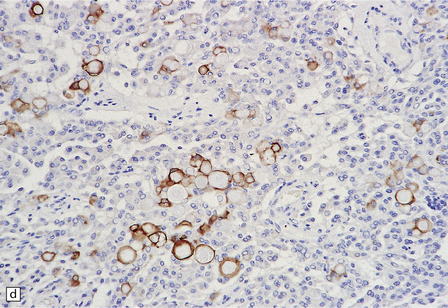

43.15 Secretory meningioma.

(a,b) This has a meningothelial or transitional pattern, but some of the cells contain eosinophilic globules. (c) The globules are PAS-positive. (d) The cells that secrete and enclose the globules show cytokeratin immunoreactivity.

43.16 Lymphoplasmacyte-rich meningioma.

(a) This variant combines dense aggregates of lymphocytes with a meningioma of transitional pattern. (b) Immunoreactivity for EMA picks out tumor cells among a sea of lymphoid cells.

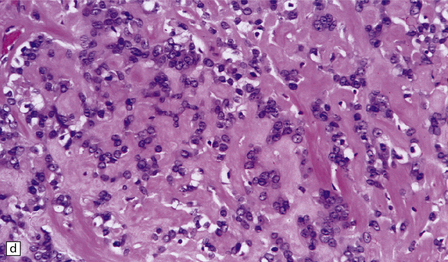

It is clear that some histologic variants have a more aggressive behavior than others, even when a meningioma’s site and the completeness of its resection have been taken into account. This variation is reflected in three levels of WHO grade (see Table 43.1). WHO grade 2 is assigned to atypical, clear cell and chordoid meningiomas (Table 43.3, Figs 43.18–43.20), which show an increased frequency of recurrence, as do grade 3 anaplastic, papillary and rhabdoid meningiomas (Figs 43.21–43.23), which are also more likely to exhibit malignant behavior, such as invasion of local structures or metastasis. Atypical and anaplastic meningiomas lie on a histologic continuum, but in the current WHO classification have been divided mainly on the basis of mitotic count (see Table 43.3). This nomenclature does not apply to meningeal sarcomas (see Chapter 45); while anaplastic meningiomas may contain sarcomatoid areas, they retain histologic features that identify them as meningiomas. The term ‘meningosarcoma’ is obsolete.

Table 43.3

Characteristics of WHO grade 2/3 meningiomas

WHO grade 2

Atypical

Increased mitotic count: ≥4/10 hpfs

With or without:

Scattered small areas of spontaneous necrosis (i.e. not related to embolization or radiotherapy)

Patternless growth

High nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio

Cells with prominent nucleoli

Chordoid

Lobulated or meningothelial architecture

Columns of vacuolated cells in a mucoid stroma plus scattered lymphoplasmacytoid infiltrates

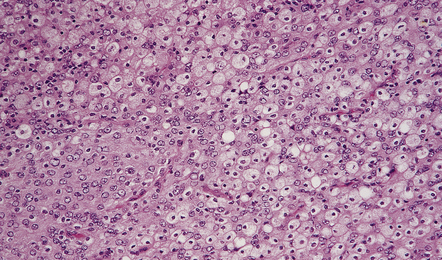

Clear cell

Sheets/lobules of oval or elongated cells with abundant intracytoplasmic glycogen

Fibrous bands/hyalinization

Sparse whorl formation

WHO grade 3

Anaplastic

Increased mitotic count: ≥ 20/10 hpfs

Usually with:

Patternless growth

Foci of marked cytological pleomorphism

Multiple large foci of spontaneous necrosis

Papillary

Found particularly in young patients

Focal perivascular (pseudo)-papillary architecture in conjunction with classic patterns

High mitotic count

Tendency to invade local structures

Rhabdoid

Groups of rhabdoid cells are found in the setting of anaplastic features

High mitotic count

Tendency to occur in recurrent tumors

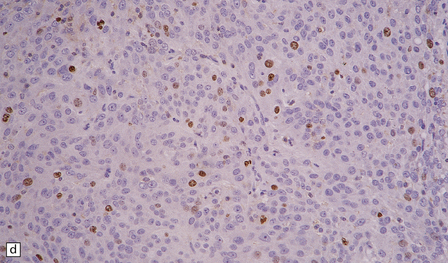

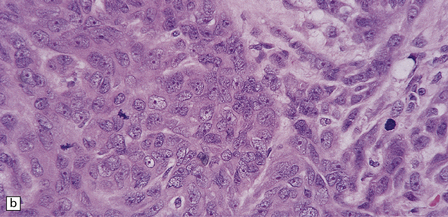

43.18 Atypical meningioma.

(a) This example contains foci of micronecrosis and lacks whorls or well-defined lobules. (b) Foci of cytological pleomorphism may be found. (c) Areas of micronecrosis are characteristic. (d) Many nuclei label with a Ki-67 antibody, and the mitotic count is ≥ 4/10 high powered fields (hpfs).

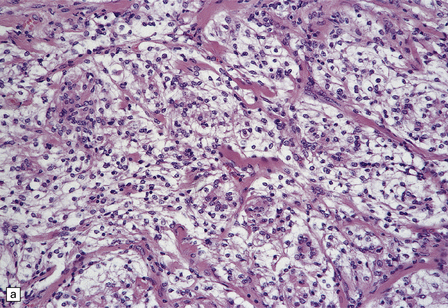

43.19 Clear cell meningioma.

(a) Groups of clear cells are divided by fibrous septa, which were particularly prominent in some areas of this neoplasm. (b) In another area from the same tumor, fibrous strands of collagen divide small groups of tumor cells, only some of which (arrow) actually show cytoplasmic clearing.

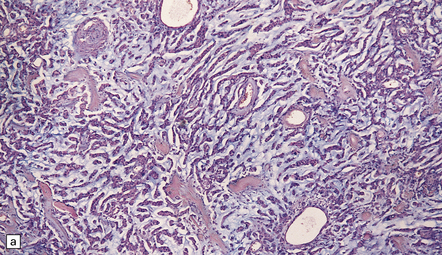

43.20 Chordoid meningioma.

(a) An abundant alcianophilic myxoid matrix surrounds small strands of meningothelial cells. The appearance mimics the histology of a chordoma, but this neoplasm can be distinguished from a meningioma by widespread immunoreactivities for S-100 and cytokeratins and its tendency to permeate bone. Also, other features of meningioma (whorls, etc.) are usually present elsewhere in the chordoid meningioma. (b) Discohesive cells are set against a myxoid matrix, and cytoplasmic vacuolation is evident in a few cells.

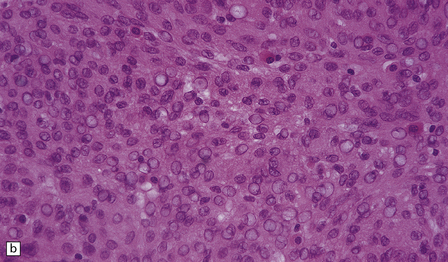

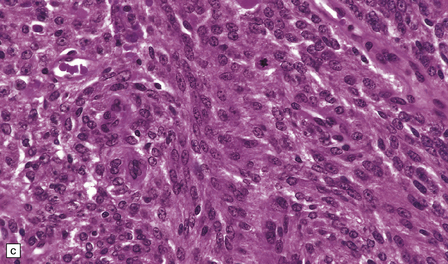

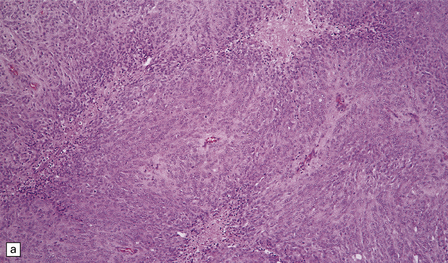

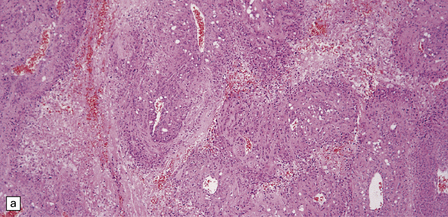

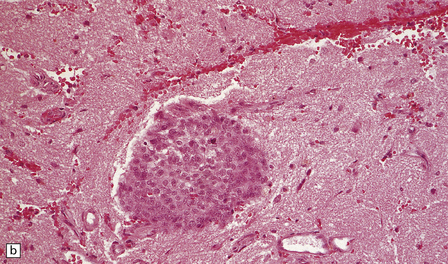

43.21 Anaplastic meningioma.

(a) This example has large areas of necrosis and marked cellular pleomorphism. (b) Note the nuclear pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, and high nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio. (c)The mitotic count exceeds 20/10 high powered fields (hpfs).

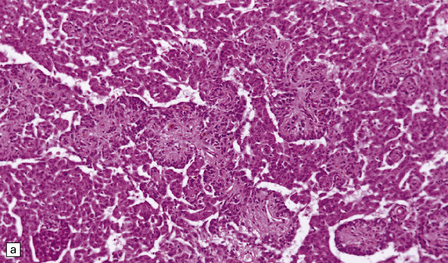

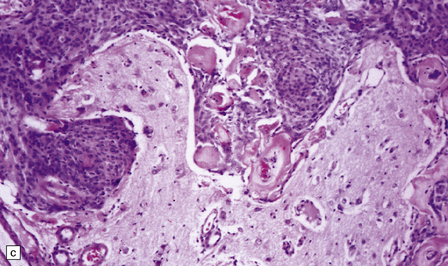

43.22 Papillary meningioma.

(a) This example consists of rather ill-defined papillary structures with perivascular clusters of meningioma cells. (b) Cells form a pseudorosette around a capillary.

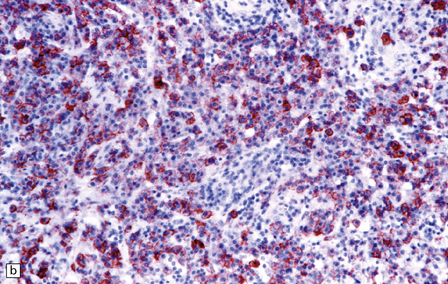

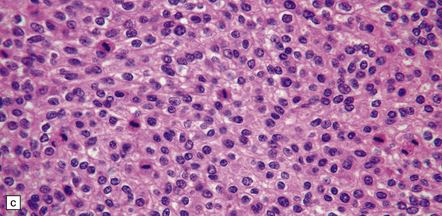

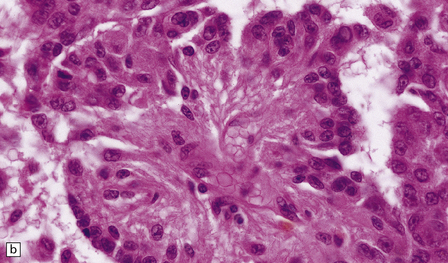

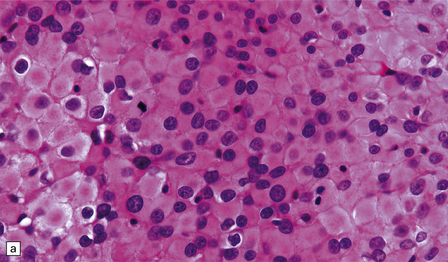

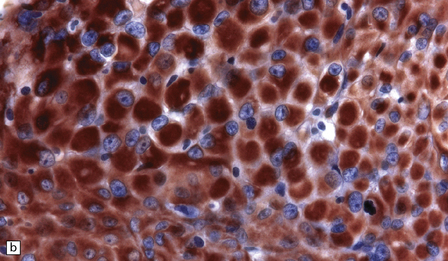

43.23 Rhabdoid meningioma.

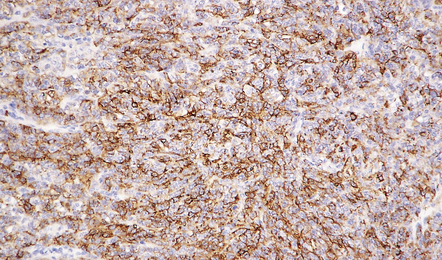

(a) Typical rhabdoid cells with eccentrically placed nuclei and a deeply eosinophilic cytoplasm are evident. Some cells contain mitotic figures. (b) The cells are very strongly immunopositive for vimentin.

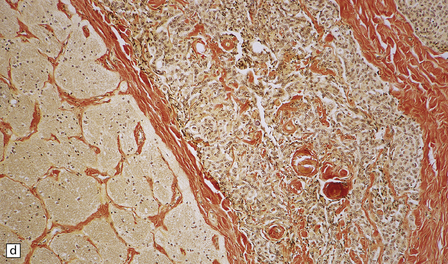

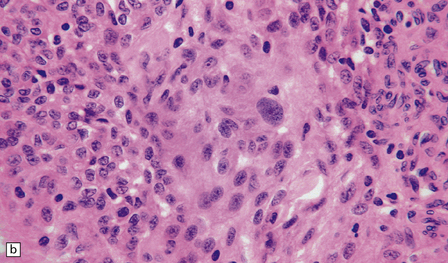

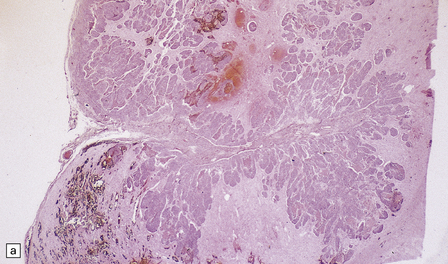

Invasion of the brain is an adverse prognostic feature (Fig. 43.24), but should be diagnosed with care. Tumor cells must breach the pia, invading brain parenchyma and eliciting reactive changes, such as astrocytosis. Superficial invasion along the subarachnoid space is not considered to be brain invasion. Brain invasion can be a feature of meningiomas that, on the basis of their cytological features, would be classified as WHO grade I, II, or III. However, when present in a meningioma with grade 1 cytological features, brain invasion is associated with an increased rate of recurrence, and such a tumor is classified as WHO grade II.

43.24 Invasion of brain by meningioma.

(a) This neoplasm extensively infiltrates the brain where (b) groups of cells have elicited a surrounding reactive astrocytosis. (c) Here the tumor has encircled part of the cerebral cortex.

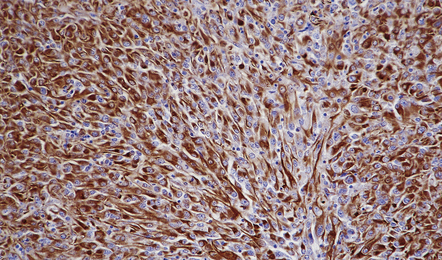

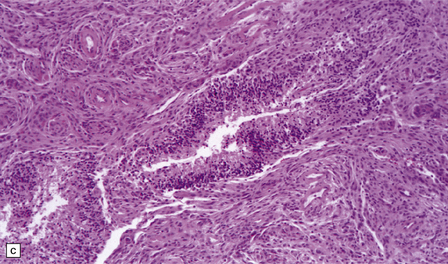

Meningiomas are immunoreactive for vimentin (Fig. 43.25), and most meningiomas, particularly those with epithelial qualities, immunolabel with antibodies to epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) (Fig. 43.26). Fibrous meningiomas tend to show only focal labeling for EMA. Approximately 25% of meningiomas show focal immunoreactivity for cytokeratins. The neoplastic cells surrounding

43.26 Meningioma immunostained for EMA.

This pattern is evident in most meningothelial neoplasms, but can be more focal in some variants.

the characteristic globules in secretory meningiomas label strongly with antibodies to cytokeratin (see Fig. 43.15d). Some meningiomas contain scattered cells that are immunoreactive for S-100 protein. There is no immunoreactivity for GFAP, except in some rhabdoid tumors.

REFERENCES

Bondy, M., Ligoni, B.L. Epidemiology and etiology of intracranial meningiomas: a review. J Neurooncol.. 1996;29:197–205.

Boström, J., Meyer-Puttlitz, B., Wolter, M., et al. Alterations of the tumor suppressor genes CDKN2A (p16(INK4a)), p14(ARF), CDKN2B (p15(INK4b)), and CDKN2C (p18(INK4c)) in atypical and anaplastic meningiomas. Am J Pathol.. 2001;159:661–669.

Epari, S., Sharma, M.C., Sarkar, C., et al. Chordoid meningioma, an uncommon variant of meningioma: a clinicopathologic study of 12 cases. J Neurooncol.. 2006;78:263–269.

Germano, I.M., Edwards, M.S., Davis, R.L., et al. Intracranial meningiomas of the first two decades of life. J Neurosurg.. 1994;80:447–453.

Haberler, C., Jarius, C., Lang, S., et al. Fibrous meningeal tumours with extensive non-calcifying collagenous whorls and glial fibrillary acidic protein expression: the whorling-sclerosing variant of meningioma. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol.. 2002;28:42–47.

Kepes, J.J. Presidential address: the histopathology of meningiomas. A reflection of origins and expected behavior? J Neuropathol Exp Neurol.. 1986;45:95–107.

Lamszus, K., Kluwe, L., Matschke, J., et al. Allelic losses at 1p, 9q, 10q, 14q, and 22q in the progression of aggressive meningiomas and undifferentiated meningeal sarcomas. Cancer Genet Cytogenet.. 1999;110:103–110.

Larson, J.J., Tew, J.M., Jr., Simon, M., et al. Evidence for clonal spread in the development of multiple meningiomas. J Neurosurg.. 1995;83:705–709.

Leone, P.E., Bello, M.J., de Campos, J.M., et al. NF2 gene mutations and allelic status of 1p, 14q and 22q in sporadic meningiomas. Oncogene.. 1999;18:2231–2239.

Longstreth, W.T., Jr., Dennis, L.K., McGuire, V.M., et al. Epidemiology of intracranial meningioma. Cancer.. 1993;72:639–648.

Ludwin, S.K., Rubinstein, L.J., Russell, D.S. Papillary meningioma: a malignant variant of meningioma. Cancer.. 1975;36:1363–1373.

Mahmood, A., Caccamo, D.V., Tomecek, F.J., et al. Atypical and malignant meningiomas: a clinicopathological review. Neurosurgery.. 1993;33:955–963.

Maier, H., Ofner, D., Hittmair, A., et al. Classic, atypical, and anaplastic meningioma: three histopathological subtypes of clinical relevance. J Neurosurg.. 1992;77:616–623.

Menon, A.G., Rutter, J.L., von Sattel, J.P., et al. Frequent loss of chromosome 14 in atypical and malignant meningioma: identification of a putative ’tumor progression’ locus. Oncogene.. 1997;14:611–616.

Olivero, W.C., Lister, J.R., Elwood, P.W. The natural history and growth rate of asymptomatic meningiomas: a review of 60 patients. J Neurosurg.. 1995;83:222–224.

Pasquier, B., Gasnier, F., Pasquier, D., et al. Papillary meningioma. Clinicopathologic study of seven cases and review of the literature. Cancer.. 1986;58:299–305.

Perry, A., Fuller, C.E., Judkins, A.R., et al. INI1 expression is retained in composite rhabdoid tumors, including rhabdoid meningiomas. Mod Pathol.. 2005;18:951–958.

Perry, A., Giannini, C., Raghavan, R., et al. Aggressive phenotypic and genotypic features in pediatric and NF2-associated meningiomas: a clinicopathologic study of 53 cases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol.. 2001;60:994–1003.

Perry, A., Scheithauer, B.W., Stafford, S.L., et al. “Rhabdoid” meningioma: an aggressive variant. Am J Surg Pathol.. 1998;22:1482–1490.

Perry, A., Scheithauer, B.W., Stafford, S.L., et al. “Malignancy” in meningiomas: a clinicopathologic study of 116 patients, with grading implications. Cancer.. 1999;85:2046–2056.

Perry, A., Stafford, S.L., Scheithauer, B.W., et al. Meningioma grading: an analysis of histologic parameters. Am J Surg Pathol.. 1997;21:1455–1465.

Rajaram, V., Brat, D.J., Perry, A. Anaplastic meningioma versus meningeal hemangiopericytoma: immunohistochemical and genetic markers. Hum Pathol.. 2004;35:1413–1418.

Riemenschneider, M.J., Perry, A., Reifenberger, G. Histological classification and molecular genetics of meningiomas. Lancet Neurol.. 2006;5:1045–1054.

Simon, M., von Deimling, A., Larson, J.J., et al. Allelic losses on chromosomes 14, 10, and 1 in atypical and malignant meningiomas: a genetic model of meningioma progression. Cancer Res.. 1995;55:4696–4701.

Stafford, S.L., Perry, A., Suman, V.J., et al. Primarily resected meningiomas: outcome and prognostic factors in 581 Mayo Clinic patients, 1978 through 1988. Mayo Clin Proc.. 1998;73:936–942.

Weber, R.G., Boström, J., Wolter, M., et al. Analysis of genomic alterations in benign, atypical, and anaplastic meningiomas: toward a genetic model of meningioma progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.. 1997;94:14719–14724.

Wellenreuther, R., Kraus, J.A., Lenartz, D., et al. Analysis of the neurofibromatosis 2 gene reveals molecular variants of meningioma. Am J Pathol.. 1995;146:827–832.

Wolfsberger, S., Doostkam, S., Boecher-Schwarz, H.G., et al. Progesterone-receptor index in meningiomas: correlation with clinico-pathological parameters and review of the literature. Neurosurg Rev.. 2004;27:238–245.