Medicolegal Issues in Obstetric Anesthesia

Mark S. Williams MD, MBA, JD, Joanna M. Davies MBBS, FRCA

Chapter Outline

DISCLOSURE OF UNANTICIPATED OUTCOMES AND MEDICAL ERRORS

CONTEMPORARY RISK MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES

LIABILITY PROFILES IN OBSTETRIC ANESTHESIA: THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF ANESTHESIOLOGISTS CLOSED-CLAIMS PROJECT

PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE STANDARDS

Childbirth is a natural process in which unexpected and potentially severe adverse events can occur. Responses to such events require timely and collaborative efforts among all caregivers. Obstetric anesthesia providers have a challenging role. Some women have high expectations about the availability and effectiveness of anesthesia services for labor and vaginal or cesarean delivery; these expectations may be influenced by the experiences and biases of family members and friends. By contrast, other women may view anesthesia for labor as an intrusion upon the natural labor process; yet, some of these women may ultimately need or request anesthesia services. The informed consent and decision-making process is fundamental to securing a woman’s understanding and support. The effectiveness of this process is subject to cultural and socioeconomic influences as well as the pain of labor.

The degree to which patients and their families possess a realistic understanding of the benefits and risks associated with childbirth and obstetric anesthesia may influence the decision to pursue legal remedies in the event of a real or perceived adverse outcome. Adverse outcomes may profoundly affect families and health care providers. Patients and their families must adjust to the reality of an unanticipated adverse outcome as well as potentially overwhelming and long-term financial costs. Physicians and other caregivers also may be profoundly affected emotionally by an adverse outcome. Medicolegal claims associated with such events (regardless of the merit of the claim) may compound such emotions, raise the costs of liability coverage, and ultimately impact the availability and overall cost of health care services.

Anesthesia providers should possess an understanding of basic medicolegal issues and should proactively embrace risk management strategies that support optimal patient care and minimize both patient dissatisfaction and the legal consequences of an unanticipated adverse outcome. Insights and opportunities for promoting safer and more effective anesthesia and obstetric care are rapidly evolving and are gaining support among payers, governmental agencies, and others.

Lawsuits Involving Claims Against Health Care Providers

Importance of Effective Communication

The ability to effectively communicate information in a manner that is understood by the patient is fundamental to securing patient understanding and cooperation. Lapses in communication may preclude obtaining truly informed consent and may lead to patient dissatisfaction, lapses in patient safety, and inadequate explanation of an unanticipated adverse outcome.

Communication failures are frequent elements in malpractice claims; these failures include lack of informed consent, poor patient rapport, language barriers, and inadequate discharge instructions, among others.1 There is an increasing recognition that limited health literacy interferes with effective communication.2 Health literacy is defined as the “degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.”3 Providers should strive to adopt methods and approaches that encourage patient engagement, reduce risk, and improve treatment compliance.4

Theories of Liability

Every physician has a duty to provide professional services that are consistent with a minimum level of competence. This is an objective standard based on the physician’s qualifications, level of expertise, and the circumstances of the particular case.5 The failure to meet this objective standard of care may give rise to a cause of action for medical negligence. The standard of care for medical practice is dynamic and changes as the profession adopts new treatments and approaches for patient care. Therefore, changes in accepted medical practice may create additional professional obligations and, in turn, additional legal responsibilities for physicians.

Although the specific medical malpractice laws vary from state to state, several different causes of action may be brought against a physician. Patients may sue for injuries resulting from the provision of health care by using one or more of three different theories (or causes of action): (1) medical malpractice, (2) breach of contractual promise that injury would not occur, and (3) lack of informed consent.6 Plaintiffs (patients) commonly file lawsuits that allege improper care on the basis of more than one of these theories (e.g., alleging both a violation of the standard of care and a lack of informed consent for the medical treatment rendered). Medical malpractice may involve failure to make the diagnosis, failure to obtain informed consent, surgical errors, drug prescription and administration errors, and other mistakes. For a plaintiff to prevail with regard to a medical malpractice claim, he or she must prove that the injury resulted from the failure of the health care provider to follow the accepted standard of care. The standard of care may be defined as “that degree of care, skill, and learning expected of a reasonably prudent health care provider at that time in the profession or class to which he belongs…acting in the same or similar circumstances.”7 This objective standard is applied to the particular facts of the plaintiff’s situation in a malpractice action.

A mistake or a bad result does not necessarily denote negligence. Similarly, unless a physician contracts otherwise with the patient (i.e., makes a promise of a specific outcome), the provision of medical care alone does not warrant or guarantee that an illness or disease will be cured. A physician is liable for a misjudgment or mistake only when it is proved to have occurred through a failure to act in accordance with the care and skill of a reasonably prudent practitioner.

Claims of medical malpractice must be filed within a certain period after the alleged incident of medical malpractice. Most jurisdictions in the United States have enacted statutes of limitations that are specifically applicable to malpractice claims. Recognizing that a significant time may elapse before symptoms or injury manifest, many states have established discovery rules that apply to situations in which the patient has no way of knowing that the injury was caused by wrongdoing or negligence. One example of an unknown injury is sterility that is discovered only when the patient attempts to conceive. Another example is the Rh-negative mother who delivers an Rh-positive child and does not receive Rho(D) immune globulin (RhoGAM). Such an injury would be apparent only when the mother has another child with Rh-positive blood. Other exceptions to—or extensions of—the statutes of limitations might involve situations of fraudulent concealment, an undiscovered foreign object, situations involving long-term continuous treatment, and issues involving infants or minors.

Establishing Medical Malpractice

In most malpractice cases, the following four elements are required for proving medical negligence:

3. Injury. It must be shown that the patient experienced an injury that resulted in damages.

4. Proximate cause. It must be shown that the negligence of the health care provider proximately caused the patient’s injury (i.e., there must be a sufficiently direct connection between the negligence of the health care provider and the injury experienced by the patient).7

If any one of these elements is missing, the plaintiff cannot establish medical malpractice. The plaintiff has the burden of proof to establish each of these elements by a “preponderance of the evidence.” This quantum of proof means that a proposition is more probably true than not true (i.e., > 50% certainty).

If the malpractice claim involves the issue of whether a physician used a proper method of treatment, the plaintiff must use expert testimony to establish that the defendant physician violated the standard of care and that such violation probably caused the plaintiff’s injury.7 Expert testimony to establish how a reasonably prudent health care practitioner would act under similar circumstances typically must be provided by an expert with the same educational background and training as the defendant physician.

In certain cases, the plaintiff may not be required to present expert testimony to prove negligence, and the burden of proof may shift to the defendant. This represents the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur (i.e., the thing speaks for itself). This doctrine has the following three conditions: (1) the injury ordinarily does not occur in the absence of negligence, (2) the injury must be caused by an agency or instrumentality within the exclusive control of the defendant, and (3) the injury must not have been a result of any voluntary action or contribution on the part of the plaintiff.5 Claims involving injuries sustained during administration of anesthesia have been made under this doctrine. In one case, a patient complained of pain that he described as a “strong electric shock” after a spinal block was administered. The patient subsequently lost all sensation below that spinal level and became incontinent. Because one would not ordinarily expect a permanent sensory loss from a spinal anesthetic, the verdict was upheld at the appellate level.8

Establishing Lack of Informed Consent

Lack of informed consent is a common cause of action in medical malpractice claims. Within the context of the physician-patient relationship, the doctrine of informed consent is based in English common law, by which doctors could be charged with the tort of battery if they had not gained the consent of their patient before the performance of surgery or another procedure. In the United States, the New York Court of Appeals established the legal principle of informed consent in 1914.9 In this case, the plaintiff, Mary Schloendorff, was admitted to a New York hospital and consented to examination under ether anesthesia to determine whether a fibroid tumor was malignant, but she withheld consent for its removal. The physician examined the tumor, found it to be malignant, and removed it—in disregard of the patient’s wishes. The Court found that this operation constituted medical battery. Writing on behalf of the Court, Justice Benjamin Cardozo wrote, “Every human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what shall be done with his own body; and a surgeon who performs an operation without his patient’s consent commits an assault for which he is liable in damages. This is true except in cases of emergency where the patient is unconscious and where it is necessary to operate before consent can be obtained.”9

This principle remains embedded in modern medical ethics and has been adopted by most state legislatures in the form of informed consent statutes. To establish negligence for failure to obtain informed consent, a plaintiff must prove (1) the existence of a material and reasonably foreseeable risk unknown to the patient, (2) a failure of the physician to inform the plaintiff of that risk, (3) that disclosure of the risk would have led a reasonable patient in the plaintiff’s position to reject the medical procedure or choose a different course of treatment, and (4) a causal connection between the failure to inform the plaintiff of the risk and the injury resulting from the occurrence of the nondisclosed risk.10

Expert testimony is typically required to establish at least some of the elements of an informed consent claim, especially the materiality of the risk. However, expert testimony is not essential if an issue falls within the general knowledge of lay persons or if the doctor failed to give the patient any information about the risks involved, because a lay person can conclude that in the absence of any information, informed consent is not possible.

The obligation to obtain informed consent lies with the physician.11 Ordinarily, the hospital or other organization has no independent duty to obtain a patient’s informed consent. Likewise, a consultant physician who advises the treating physician has no such duty. A referring physician is not required to obtain informed consent unless he or she actually participates in or controls the subsequent treatment by the other physician.12

There are differences of opinion as to the perspective to be embraced when a physician is disclosing the nature and likelihood of a given risk. Specifically, should it arise from the patient’s or the physician’s point of view? Theoretically, both would desire the same scope of disclosure. Often, the pivotal issue is the determination of which party’s viewpoint should dictate the standard for judging the physician’s conduct.13 Most jurisdictions use a “reasonable person” or “prudent patient” standard. Under this rule, a physician is expected to disclose to the patient in lay terms all material information that a prudent or reasonable patient would consider significant to making his or her decision.14 This approach concerns itself with the patient’s needs, rather than the physician’s judgment; this approach follows the rationale that the physician should neither impose his or her values on the patient nor substitute his or her level of risk aversion for that of the patient.15 Under this standard, the jury determines whether a reasonable person in the plaintiff’s position would have considered the risk significant in making his or her decision. The issue is not what a particular patient would want to know but rather what a reasonable person in the patient’s condition would want to know, taking into account factors such as the individual’s medical condition, age, and risk factors.16 This objective standard protects physicians from potentially self-serving testimony of plaintiffs, who inevitably assert that they would have refused a given procedure if they had been properly informed of the risk.

The materiality of risk is an issue under this “reasonable” or “prudent” patient standard. It is generally accepted that a physician is not required to present every possible risk of a proposed treatment. If the probability of its occurrence is practically nonexistent, then the risk, no matter how severe, is not material. Conversely, even a small risk for occurrence may be significant to a patient’s decision if the potential consequences could be severe.17 Disputes concerning the proper scope of disclosure tend to center on whether the risk was foreseeable or remote.

Some jurisdictions still adhere to the professional standard of disclosure. This approach assumes the perspective of the physician and is concerned with what information a reasonable practitioner would share with a patient under the same or similar circumstances.18

Even in circumstances in which the health care providers acknowledge their failure to provide important information to the patient or the patient’s legally authorized surrogate decision-maker, the jury is still asked to decide whether the patient or the patient’s decision-maker would have consented to such a course of treatment despite the risk. For example, in Barth v. Rock, a 5-year-old patient suffered a cardiac arrest (and eventual death) after receiving general anesthesia by mask with sodium thiopental, nitrous oxide, and a succinylcholine infusion for open reduction of an arm fracture. Both the surgeon and the nurse anesthetist admitted that they failed to inform the minor patient’s parents about the risks of general anesthesia. The appellate court held that the jury should have been instructed that, as a matter of law, there was no informed consent; the jury then should have decided whether the parents would have consented to the anesthesia had they been adequately informed of the risks.19

If a plaintiff establishes the four elements for a cause of action based on lack of informed consent, the burden shifts to the physician to establish a defense that justifies why the material information was not provided (e.g., the insignificant nature of the risk) or why disclosure would not have altered the chosen course of treatment. In addition, the health care providers may claim that the case was a medical emergency. State laws generally supply a defense of “implied consent” for provision of necessary emergency treatment when the patient is unable to provide his or her own consent and no legally authorized surrogate decision-maker is immediately available.20 If the health care providers’ treatment was authorized under a medical emergency, the providers should carefully document their determination of same. The documentation in the patient’s medical record should contain a description of the patient’s presenting condition, its immediacy, its magnitude, and the nature of the immediate threat of harm to the patient. It is advisable for at least two health care providers to document this information, because the documentation would support their actions if a lack-of-informed-consent lawsuit were filed. The “emergency treatment” rule is limited in two respects. First, the patient must require immediate care to preserve life or health. Second, the physician may provide only the care that is reasonable in light of the patient’s condition.

The Litigation Process

It is helpful for health care providers to have a basic understanding of sources of law, how lawsuits are initiated, and typical steps in the litigation process.

Sources of Law

Legal authority has multiple sources, including federal and state constitutions, federal and state statutes, federal and state regulations, and federal and state case law. Constitutions are the fundamental laws of a nation or state, which establish the role of government in relation to the governed. Constitutions act as philosophical touchstones for the society, from which other ideas may be drawn. One example is the “right to privacy” established in case law, which flows from the constitutional recognition of individual liberty.21 Statutes are the laws written and enacted by elected officials in legislative bodies. Regulations are written by government agencies as permitted by statutory delegation. Although regulations have the force and effect of law, they must be consistent with their enabling legislation. Case law refers to written opinions or decisions of judges that arise from individual lawsuits. Case law that may be cited as legal authority (precedent) is limited to cases at the appellate court level (i.e., cases appealed from trial court decisions). The vast majority of lawsuits settle before trial, and only a small percentage of trial court decisions result in appeal; thus, case law reflects a very small portion of actual litigation. Like medicine, the practice of law is dynamic and changes as new legislation and regulations are adopted or new case law is created. In addition, any one or several of these sources of law may be relevant to a particular case.

When creating new laws or applying the law in deciding the proper result for a particular case, a legislative body or a court may also consider other information about standards for health care providers’ conduct. For example, the court may give strong weight to The Joint Commission standards and find that a provider acting in accordance with The Joint Commission requirements was adhering to his or her professional obligations.22 In writing legislation or court decisions, lawmakers also may defer to standards and practice guidelines adopted by professional organizations, such as the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA). The adoption of professional standards and practice guidelines strengthens the influence of professional organizations in the lawmaking process because lawmakers often are willing to defer to professional organizations’ statements on standards of care and professional ethics.

Some experts have suggested that the value of “evidence-based” guidelines within the venue of medical malpractice has been disappointing, primarily because of a lack of scientific evidence supporting the guidelines.23 A 2009 analysis of guidelines issued by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association determined that “the significant increase in the quantity of scientific literature concerning cardiovascular disease published in recent years (along with the number of technical and medical advances)—if aimed to address unresolved issues confronting guideline writers—should have resulted in guideline recommendations with more certainty and supporting evidence.”24 Recent federal regulation dictates the funding of some comparative effectiveness studies that may provide additional evidence on which to base clinical guidelines.25 It will be several years before the merit of these investments can be assessed.

Initiation of a Lawsuit

Medical malpractice lawsuits are typically initiated when a plaintiff files a complaint with the court. Some states have enacted statutes that impose certain conditions (including notification of the defendant physician) before a complaint is filed.26 The physician receives notice of the legal action when he or she is served with a copy of the summons and the complaint. In the complaint, the plaintiff alleges the facts giving rise to the cause(s) of action against the physician. The complaint requires a written answer to be filed (by the attorney representing the physician) with the court within a specified period. If a timely answer is not filed, a default judgment may be entered against the physician (i.e., a judgment is allowed because no response may be treated as no defense against the allegations).

In civil actions against health care providers, plaintiffs are frequently motivated to sue for an award of monetary damages. Medical malpractice lawsuits may involve multiple defendants, such as the treating physician, the hospital, manufacturers of health care equipment, and pharmaceutical companies. Defense counsel evaluates its client’s potential liability exposure (i.e., any aspect of care arguably not meeting the standard of care). Both plaintiff counsel and defense counsel weigh the perceived risks if the case proceeds to trial and then determine how much they think the case is worth. The valuation of a case may include more than the estimated dollar value; it may also include considerations such as setting a potential precedent or maintaining a business relationship.

Discovery

Discovery refers to the early phase of litigation after a lawsuit is initiated. During this phase, the litigants on both sides research the strengths and weaknesses of their cases by obtaining and examining medical records, reviewing medical literature, and interviewing and deposing witnesses, including the plaintiff(s), the treating health care provider(s), and potential expert witnesses.

During discovery, certain methods of gathering information are generally used. The methods include interrogatories and depositions. Interrogatories are written questions that are served on one party from an opposing party. Interrogatories must be answered in writing, under oath, within a prescribed period. Failure to respond as required may result in the court’s issuing sanctions against the nonresponding party. Depositions involve testimony given under oath that is recorded by a court reporter. In a deposition taken for the purpose of discovery, the attorneys representing all opposing litigants participate and ask questions of the witness. The purposes of discovery depositions are (1) to obtain facts and other evidence, (2) to encourage the other side to commit to a position “on the record” (i.e., in preserved testimony), (3) to discover the names of other potential witnesses, (4) to assess how strong a witness the deposed individual may make, (5) to limit facts and issues for the lawsuit, (6) to encourage the other side to make admissions against its own interests in the lawsuit, and (7) to evaluate the case for its dollar (or other) value and potential for settlement.

Trial

A trial typically consists of (1) jury selection, (2) opening statements, (3) plaintiff’s trial testimony, (4) defendant’s trial testimony, (5) closing arguments, (6) jury instructions given by the judge, and (7) delivery of the jury’s verdict. There also may be post-verdict proceedings and motions. The lawyers for all parties file briefs with the court in advance of the trial to outline the case for the trial judge. The lawyers also prepare and argue over the content of jury instructions, seeking the best language to support their theories of the case. The judge decides which jury instructions will be given and reads them to the jurors immediately prior to jury deliberation. Attorneys commonly file motions about significant trial proceedings, such as the scope of admissible evidence. The trial judge rules on these motions outside the presence of the jury.

A jury verdict does not necessarily end the case. If a verdict in favor of the plaintiff(s) is reached, defense counsel may file a motion (1) asking the court to set aside the verdict and grant a new trial, (2) asking the court to change the verdict and enter a judgment in the defendant’s favor, or (3) asking for a reduction in the amount of damages awarded to the plaintiff(s). Defense counsel also may seek to reopen settlement negotiations or may choose to appeal the case. The plaintiff(s) may take similar post-verdict steps if the jury renders a verdict in favor of the defendant(s).

The vast majority of medical malpractice cases never go to trial. A 1991 study showed that only 2% of persons injured by physicians’ negligence ever file a lawsuit.27 Subsequently, only 10% of all medical malpractice claims go to trial. Settlement negotiations result in the disposal of many cases. Other cases are withdrawn by plaintiffs or are dismissed by the court on legal grounds such as summary judgment, whereby a judge may rule that a plaintiff’s case is legally insufficient. Defendants win approximately 71% of medical malpractice claims.28

In seeking alternatives that might speed the litigation process and reduce the overall costs, a number of states have created medical pretrial screening panels. As an alternative to a full trial, a medical screening panel is typically comprised of several physicians and an attorney, who determine whether the defendant met the appropriate standard of care and if the injury was proximately caused by a failure to meet that standard. The findings of the group are then submitted to the court for further adjudication.29 The effectiveness of this model is subject to considerable debate. Other alternatives include arbitration, mediation, and other types of alternative dispute resolution.

Informed Consent

Process and Documentation

A patient’s right of self-determination lies at the root of informed consent. A patient can make an informed decision only after (1) a discussion of the diagnosis and the indications for the procedure or therapy; (2) disclosure of material risks, benefits, and alternatives; and (3) provision of an opportunity for questions and answers. This process is neither accomplished nor affirmed solely by having the patient’s or the patient surrogate’s signature on a document asserting informed consent. Evidence of this process and the physician’s involvement in the process may be found among office notes, informational aids shared with patients, hospital notes, and signed forms acknowledging informed consent.

The necessity of having a specific process is not only an ethical obligation but also a requirement of various state and federal agencies. For example, the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have Conditions of Participation that define the requirements that facilities must satisfy to participate in the Medicare and Medicaid programs. Specifically, the Patients’ Rights Conditions of Participation contain the following interpretive guidelines: “Hospitals must utilize an informed consent process that assures patients or their representatives are given the information and disclosure needed to make an informed decision about whether to consent to a procedure, intervention, or type of care that requires consent.”30 Further, the interpretive guidelines for the CMS Surgical Services Conditions of Participation specifically state the following31:

The primary purpose of the informed consent process is to ensure that the patient, or the patient’s representative, is provided information necessary to enable him/her to evaluate a proposed surgery before agreeing to the surgery. Typically, this information would include potential short and longer term risks and benefits to the patient of the proposed intervention, including the likelihood of each, based on the available clinical evidence, as informed by the responsible practitioner’s professional judgment. Informed consent must be obtained, and the informed consent form must be placed in the patient’s medical record, prior to surgery, except in the case of emergency surgery.

The interpretive guidelines note that there is no specific requirement for informed consent governing anesthesia services but also state that “given that surgical procedures generally entail the use of anesthesia, hospitals may wish to consider specifically extending their informed consent policies to include obtaining informed consent for the anesthesia component of the surgical procedure.”31

As patients have become more engaged in their health care and are reaching out to nontraditional sources of information, other approaches to ensuring informed consent have been proposed. Studies have demonstrated that standard counseling often results in inadequate decision quality.32 Some patients may have an incomplete understanding of the risk and benefits of a treatment, and clinicians are often poor judges of patients’ values; consequently, there may be overuse of treatments that informed patients would not choose or value.33 Thus, decision-making aids are used to improve the quality of informed consent and to reduce unnecessary practice variations by (1) providing facts about the condition, options, outcomes, and risks; (2) clarifying patients’ evaluations of the outcomes that are most meaningful to them; and (3) guiding patients in the steps of deliberation and communication so that a choice can be made that reflects their informed values. These decision-making aids may be used by practitioners and/or patients in either individual or group settings, and they may be presented in a variety of formats, such as print, video, the Internet, and interactive devices.33 In essence, this approach attempts to address the weaknesses in both the “reasonable patient” and the “professional standard” approaches to disclosure, and it becomes even more valuable as the diversity of practitioners and patients increases.

Formal documentation of informed consent has other advantages. Adequate documentation helps health care providers defend their actions if patients subsequently challenge their consent for health care. In some jurisdictions, a valid consent form signed by the patient may provide a direct means of defense and actually shift the burden of proof to the plaintiff who wishes to make a claim of lack of informed consent.34 Some large medical liability insurance providers have strongly recommended that the clinician responsible for providing anesthesia care should obtain a separate written consent.35 Further, some anesthesia organizations have recommended not only that an anesthesia-specific form should be used but also that practitioners should highlight specific risks that may be present.36 A separate anesthesia consent form that highlights specific risks demonstrates a meaningful effort to engage patients in a full discussion of relevant issues and may help establish the basis of a potential defense against a medical malpractice claim. It may also reinforce the importance and significance of anesthesia services and choices in the obstetric setting.

In discussing anesthetic options for a given procedure, anesthesia providers should consider several aspects, including the best options given the skill set of the provider, the comorbidities of the patient, and the preferences of the surgeon. In a review of anesthesia consent procedures, O’Leary and McGraw37 recommended that an explanation of the relevant risks and benefits of alternative techniques as well as the likelihood and details of a backup plan should be included in informed consent. The investigators recommended that anesthesia providers adopt a separate, written consent form for the administration of anesthesia services. A form that clearly delineates common risks but allows documentation of patient-specific risks should be used. Ideally, the anesthesia provider should obtain the patient’s consent for anesthesia and should not rely on other professionals who are not competent to explain the risks and benefits of anesthesia options.

Capacity to Consent/Mental Competence

Physicians are bound by ethics and required by law to obtain a patient’s informed consent before initiating treatment. This premise assumes that a patient is competent and/or has the capacity to successfully participate in this process. Competence generally refers to the patients’ legal authority to make decisions about their health care. Adult patients, typically 18 years of age or older, are presumed to be legally competent to make such decisions unless otherwise determined by a court of law. Capacity typically focuses on the clinical situation surrounding the informed consent process. For example, an otherwise normal patient who has been given sedation may be legally competent but temporarily incapacitated and therefore unable to give informed consent.38 The determination as to whether a patient has the capacity to provide informed consent generally is a professional judgment made by the treating health care provider. However, if a court has made a judgment regarding a patient’s capacity to make such decisions, the health care provider(s) should obtain a copy of the court order, because it may delineate whether the patient is considered able to make his or her own health care decisions. For example, a guardianship is a type of court proceeding that may have an impact on the informed consent process. If a patient has a legal guardian with the authority to make health care decisions on behalf of the patient, that guardian should be consulted about the patient’s care and is the person legally authorized to provide consent. A failure to recognize a lack of capacity may expose a physician to liability for treating a patient without valid informed consent.

The legal standards for decision-making capacity vary among jurisdictions but generally encompass the following criteria: The patient must be able to (1) understand the relevant information, (2) appreciate the situation and its consequences, (3) reason about treatment options, and (4) communicate a choice.39 When the patient is unable to do so, surrogate decision-makers may be sought. In emergency situations, physicians can provide necessary care under the presumption that a reasonable person would have consented to the anticipated treatment.40 Most states have laws that delineate who is legally authorized to provide consent for health care decisions on behalf of an incapacitated individual. State laws vary, but they typically provide a list of persons (in order of priority) who may give consent. These laws assume that legal relatives are the most appropriate surrogate decision-makers. However, the competent patient is free to select any competent adult to act as his or her health care decision-maker by executing a durable power of attorney for health care, which appoints that person as his or her agent.

Health care providers are required to make reasonable efforts to locate a person in the highest possible category to provide consent. If there are two or more persons in the same category (e.g., adult children), then the medical treatment decision must be unanimous among those persons. These surrogate decision-makers generally are required to make “substituted judgment” decisions on behalf of the patient (i.e., they are obligated to decide as they believe the patient would, not as they may prefer). If what the patient would want under the circumstances is unknown, then the surrogate must make a decision consistent with the patient’s “best interests.”41 The surrogate decision-maker has the authority to provide consent for medical treatment, including nontreatment.

Minor Patients

Existing laws regarding the ability of minors to provide their own consent for medical care may be viewed as a patchwork quilt. Statutes and case law differ from state to state. There are three ways in which a minor may be deemed able to give his or her own consent for medical care: (1) by state law that permits the minor to consent for the specific type of care, (2) by a clinical determination made by the health care providers that the minor is mature and emancipated for consent purposes, and (3) by a judicial determination of emancipation.

Parental involvement in a minor’s health care decisions is usually desirable. For most health care decisions, a parent is required to provide consent for medical treatment of a minor patient.42 However, many minors will not take advantage of some available medical services if they are required to involve their parents.43 The list of services for which minors can legally give consent has recently expanded to include (1) sexual and reproductive health care, (2) mental health services, and (3) alcohol and drug abuse treatment. The majority of states also permit minor parents to make important health care decisions regarding their own children.

In most states, consent laws apply to minors 12 years of age and older. For example, 26 states and the District of Columbia allow minors (12 years of age and older) to consent to contraceptive services. All states and the District of Columbia allow minors to consent to treatment for sexually transmitted infections. Thirty states and the District of Columbia allow minor parents to consent to medical care for their children. For some medical treatment, including contraception and obstetric care, case law has generally held that minors have rights of privacy and autonomy that are fundamental and equivalent to the rights of adults.44

In addition to statutes and case law regarding a minor’s ability to provide consent, there also exists a broader legal concept—the emancipated or mature minor doctrine.45 This doctrine allows health care providers to determine whether a minor is emancipated for providing medical consent. Case law may not give a precise definition of an emancipated minor, but it may list criteria that health care providers should consider. Such criteria may include the minor’s age, maturity, intelligence, training, experience, economic independence, and freedom from parental control. When a minor is deemed emancipated for medical consent, the health care provider should document the objective facts that support the emancipation decision, consistent with institutional policies and/or other legal guidance.

Some states have adopted emancipation statutes that permit minors to file for emancipation status in court.46 Typically, a minor is required to be a minimum age to file for emancipation. Once the court grants emancipation status, a minor generally has the right to give informed consent for health care. A signed copy of the court’s emancipation order should be placed in the patient’s medical record.

Emancipation per se does not alter the requirement that a patient provide informed consent for medical treatment, including nontreatment. Emancipation status affords the minor patient rights (for providing consent) that are equal to those of an adult patient. The emancipated minor (like any adult patient) must have the ability to weigh the risks and the benefits of the proposed treatment or nontreatment.

In summary, health care providers typically should obtain consent from the minor’s parents before providing nonemergency treatment unless the minor is emancipated (by either a clinical or judicial determination) or the minor is permitted by statute to give consent to the type of health care sought.

Consent for Labor Analgesia

It is common practice for surgical patients to sign a preoperative consent form, which often includes a statement giving consent for anesthesia. The situation in obstetrics is somewhat different in that not all laboring women require operative delivery. Several years ago, an unpublished survey of obstetric centers in the greater Seattle, Washington, area revealed that approximately half of the institutions did not require a signed consent form for obstetric procedures other than cesarean delivery. At many of these institutions, a separate written consent signed by the patient is not obtained before administration of anesthesia. A 1995 survey of obstetric anesthesiologists in the United States and the United Kingdom indicated that 52% of U.S. anesthesiologists (but only 15% of U.K. anaesthetists) obtained a separate written consent for epidural analgesia during labor.47 In a survey performed in the United Kingdom in 2007,48 only 7% of obstetric units routinely obtained written informed consent for epidural analgesia during labor. In a 2004 survey from Australia and New Zealand,49 less than 20% of anesthesia providers obtained written consent before initiating neuraxial labor analgesia.

Some health care facilities and organizations have begun using a consent form for obstetric and anesthetic procedures that may be desired or necessary during labor and delivery. The process of reviewing and signing the consent form provides a specific opportunity for the patient to ask questions. It also provides additional documentation that consent was obtained. The combined form has the additional advantage of not requiring the patient to sign multiple medicolegal documents. Although a signed consent form is not necessary, it should be standard practice for anesthesia providers to document that verbal informed consent was obtained before administration of anesthesia.

Ideally, the anesthesia provider will discuss anesthetic options before the patient is in severe pain and distress. Unfortunately, the anesthesia provider often first encounters the patient when she is in severe pain. Although the provider may tailor the consent process to the circumstances, the presence of maternal pain and distress does not obviate the need for a frank discussion of the risks of anesthesia as well as the alternatives. A survey of Canadian women revealed their strong preference to be informed of all possible complications of epidural anesthesia, especially serious ones, even when the risk was quite low.50 This study and others have emphasized that parturients desire to have these discussions as early in labor as possible.

Gerancher et al.51 performed a study to evaluate the ability of laboring women to recall the details of a preanesthesia discussion and to determine whether verbal consent alone or a combination of verbal and written consent provided better recall. The investigators randomly assigned 113 laboring women to one of two groups, those from whom verbal consent alone was obtained and those from whom verbal consent plus written consent was obtained. The verbal-plus-written consent group had significantly higher median (range) recall scores (90 [80-100]) than the verbal-only group (80 [70-90]). Only two women (both in the verbal group) believed that they were unable (because of either inadequate information or situational stress) to give valid consent. The investigators concluded that “the high recall scores achieved by the women in both groups suggest that the majority of laboring women are at least as mentally and physically competent to give consent as preoperative cardiac patients.”

Clark et al.52 randomly assigned hospital inpatients to receive either an oral anesthesia discussion alone or both an oral anesthesia discussion and a preprinted anesthesia consent form. In contrast to the results of Gerancher et al.,51 these investigators found that “patients remembered less of the information concerning anesthetic risks discussed during the preoperative interview if they received a preprinted, risk-specific anesthesia consent form at the beginning of the interview.” They speculated that “patients who see an anesthesia consent form for the first time during the preoperative interview may try to read and listen simultaneously, and with their attention divided, may remember less of the preoperative discussion.”

Anesthesia providers have expressed concern about the adequacy of the informed consent process when women are experiencing the severe pain of active labor. A 2005 study evaluated whether labor pain and neuraxial fentanyl administration affect the intellectual function of laboring women.53 The Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) was used to evaluate orientation, registration, attention, calculation, recall, and language both before and after initiation of analgesia in 41 laboring women. There was no difference in MMSE scores before and after administration of neuraxial analgesia.

In summary, it seems reasonable for the patient to provide her signature as evidence of her consent, if her condition permits. This consent can be furnished on a separate anesthesia consent form or as part of a consent form for all obstetric care, including anesthesia. A signed consent form is preferable, but it should be standard practice for the anesthesia provider to explain the intended procedure, risks, and alternatives and to document this discussion in the medical record.

Refusal of Care

Documentation

Competent adult patients may refuse medical treatment, including life-saving care.42 Health care providers generally determine whether a patient is capable of making medical treatment choices (see earlier discussion). In theory, the health care providers’ clinical judgment about a patient’s capacity to provide informed consent is the same regardless of whether the patient approves or disapproves the treatment plan. In practice, however, these situations are often handled differently. When a patient consents to the recommended medical treatment, minimal scrutiny of his or her decision-making capacity is typically made. However, when a patient refuses potentially life-saving treatment, a higher level of scrutiny is applied to the patient’s ability to understand and make a choice for nontreatment. Determination of a patient’s capacity to give informed consent is typically a clinical judgment. State law may provide some definitions as to when a person may not be competent.

If a patient refuses potentially life-saving treatment, the health care providers should carefully assess the patient’s capacity to provide informed consent. It may be advisable to obtain a psychiatric consultation as part of this clinical determination. It is important to document the determination of capacity and the objective facts supporting the decision. If a patient is deemed able to provide consent, he or she is able to either choose or reject the recommended treatment plan. Institutional policies may require the patient (or health care provider if the patient refuses) to sign an “Against Medical Advice” form for a non–medically approved discharge. If a patient is deemed unable to consent, the health care providers should obtain consent from a legally authorized surrogate decision-maker on the patient’s behalf. If an incompetent patient needs emergency medical care, it may be provided consistent with an “emergency exception” (see earlier discussion).

Conflicts Arising out of the Maternal-Fetal Relationship

Almost all pregnant women consider the welfare of their unborn child to be of utmost importance. However, there may be situations in which maternal and fetal interests appear divergent or, potentially, in conflict. One example is when a pregnant woman refuses a diagnostic procedure, a medical treatment, or a surgical procedure that is intended to enhance or preserve fetal well-being. Another may arise when the pregnant woman’s behavior is considered harmful to the fetus.54 Physicians who care for pregnant women may confront challenging dilemmas when their patients reject medical recommendations, use illegal drugs, or engage in other behaviors that may adversely affect fetal well-being.

Appellate court decisions typically have held that a pregnant woman’s decisions regarding medical treatment take precedence over the presumed fetal consequences of the maternal decisions.55 One case illustrates the evolution of this judicial approach. Angela Carder was a 26-year-old married woman who had had cancer since age 13 years. At 25 weeks’ gestation she was admitted to George Washington University Hospital, where a massive tumor was found in her lung. Her physicians determined that she would die within a short time. Her husband, her mother, and her physician agreed with her expressed wishes to be kept comfortable during her dying process. Ultimately, the hospital sought judicial review of this course of action. The hospital asked whether a surgical delivery should be authorized to save the potentially viable fetus. The situation was presented to a judge, who authorized an emergency cesarean delivery without first ascertaining (using the principle of substituted judgment) the patient’s wishes. A cesarean delivery was performed without full consideration of the patient’s wishes, the infant died approximately 2 hours after delivery, and the mother died 2 days later.

This case spawned extensive debate as to whether coercive intervention to protect the fetus is ever morally and legally justifiable.56 With the assistance of the American Civil Liberties Union, Angela’s parents sued the hospital, 2 administrators, and 33 physicians for claims including battery, false imprisonment, discrimination, and medical malpractice. These civil lawsuits were settled after several years of litigation, and as part of this process, the hospital adopted a written policy concerning decision-making for pregnant patients.57 The court later reversed its initial decision authorizing the surgical delivery and ultimately issued an opinion setting forth the legal principles that should govern the doctor–pregnant patient relationship.58 The court stated, “In virtually all cases the question of what is to be done is to be decided by the patient—the pregnant woman—on behalf of herself and the fetus. If the patient is incompetent…her decision must be ascertained through substituted judgment.” In affirming that the patient’s wishes, once ascertained, must be followed in “virtually all cases” unless there are “truly extraordinary or compelling reasons to override them,” the court did not foreclose the possibility of exceptions to this rule.

Many contemporary medical ethicists agree that a pregnant woman’s informed refusal of medical intervention should prevail as long as she has the capacity to make medical decisions.59 Newer legislation and some high-profile legal cases (some involving criminal prosecution) have challenged this notion and have raised the question of whether there are circumstances in which a pregnant woman’s rights to informed consent and bodily integrity may be subordinated to protect her unborn child. In 2004, Amber Rowland, a woman who had given birth vaginally to six children (with birth weights up to 12 pounds), was told by her treating physicians at a Pennsylvania hospital that she should undergo a cesarean delivery on the basis of an ultrasonographic examination that suggested an estimated birth weight of 13 pounds. When she refused, the hospital obtained a court order for a “medically necessary” cesarean delivery. She and her husband left the hospital against medical advice and went to another facility, where she uneventfully delivered a healthy 11-pound daughter.60

Other cases have focused on the pregnant woman’s potentially harmful behavior. In 1991, Regina McKnight, who was pregnant at the time, began using cocaine after her mother’s death. She had a stillbirth, and the state of South Carolina charged her with homicide by child abuse, claiming that her drug use caused the stillbirth. She became the first South Carolina woman to be convicted of this crime, for what both the defense and prosecution agreed was an unintentional stillbirth, and she spent nearly 8 years in jail. In 2008, the South Carolina Supreme Court unanimously reversed her conviction on the grounds that she did not receive a fair trial, primarily on the basis that her attorney failed to challenge the science that was used to convict her.61

Also in 2008, the Southern Poverty Law Center, along with 25 medical, public health, and health advocacy groups, filed an amicus curiae brief against the prosecution of pregnant women in Covington County, Alabama, subsequent to the following event. Shekelia Ward delivered an infant on January 8, 2008. Both she and her newborn tested positive for cocaine during their hospital stay, and the facility reported it to authorities for possible child abuse.62 The following day she was arrested, imprisoned, and charged with a felony—chemical endangerment of a child. The state statute at issue was passed by the Alabama legislature in 2006, for the purpose of prosecuting parents who exposed children to the toxins associated with methamphetamine production; the statute did not mention pregnant women or their fetuses.63

These statutes reflect the concept that a fetus can and should be treated as separable and legally, philosophically, and essentially independent from the mother.55 The refinement of techniques of intrauterine fetal imaging, testing, and treatment prompted the view that fetuses are independent patients who can be treated directly while in utero.64 The prominence of some ethical models that have asserted that physicians have moral obligations to fetal patients separate from their obligations to pregnant women also contributed to these developments.65 Finally, a number of laws (primarily passed at the state level) were enacted with the aim of defining fetal rights separate from a pregnant woman’s rights. In 2011, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women issued a statement addressing the issue of substance abuse reporting and the role of the obstetrician.66 This document described a “disturbing trend” in legal actions and policies that criminalized drug abuse during pregnancy when such abuse is thought to be associated with fetal harm or adverse outcomes. Noting that women seeking obstetric care should not be exposed to criminal or civil penalties and that few treatment facilities are available to effectively treat drug abuse in pregnancy, the ACOG concluded that the use of the legal system to address alcohol and substance abuse issues is inappropriate and urged that policy makers and legislators instead focus on strategies to address the needs of pregnant women with addictions.

The American Medical Association (AMA) has taken a similar position, stating that (1) drug addiction is a disease amenable to treatment, rather than a criminal activity, and (2) there is a pressing need for maternal drug treatment and supportive child protective services.67 Any legislation that criminalizes maternal drug addiction or requires physicians to function as agents of law enforcement will be opposed by the AMA.67

During the past two decades, practitioners have only infrequently resorted to court-ordered interventions against the wishes of the pregnant woman. In overturning the previous court’s decision in the Angela Carder case (mentioned earlier), the Washington, DC, Court of Appeals noted that if a pregnant woman makes an informed decision, “her wishes will control in virtually all cases.”58 The court added, “We do not foreclose the possibility that a conflicting state interest may be so compelling that the patient’s wishes must yield, but we anticipate that such cases will be extremely rare and truly exceptional.”58

Medical ethicists and practitioners agree that clear communication and patient education represent the best means to address maternal-fetal conflict. Failing resolution, a 1999 ACOG opinion offered the following three options: (1) respect the patient’s autonomy and not proceed with the recommended intervention regardless of the consequences, (2) offer the patient the option of obtaining medical care from another individual before conditions become emergent, and (3) request that the court issue an order to permit the recommended treatment.68 In 2004, the ACOG addressed the situation in which health care providers may consider this last option (i.e., legal intervention against a pregnant woman).54 Specifically, the ACOG stated that the following criteria should be satisfied: (1) “there is a high probability of serious harm to the fetus in respecting the patient’s decision”; (2) “there is a high probability that the recommended treatment will prevent or substantially reduce harm to the fetus”; (3) “there are no comparably effective, less intrusive options to prevent harm to the fetus”; and (4) “there is a high probability that the recommended treatment [will] also benefit the pregnant woman or that the risks to the pregnant woman are relatively small.”

The ACOG opinions assume the presence of competency and informed consent. Thus, if a pregnant patient is believed to be incompetent and incapable of providing informed consent, the health care providers may not be required to respect the patient’s refusal of care. Moreover, if the patient is deemed incompetent and/or a medical emergency exists, care may be provided with consent from a legally authorized surrogate decision-maker or as an “emergency exception.”

In summary, two approaches are available to the practitioner dealing with maternal-fetal conflict. One approach is to honor a competent pregnant patient’s refusal of care. The other approach (which appears least favored by many medical ethicists and the ACOG) is to seek judicial authorization of treatment, which overrides a competent pregnant woman’s refusal of care.69

In honoring a competent patient’s desires to refuse treatment, the health care providers should carefully document the woman’s competency and ability to provide informed consent. Every attempt should be made to counsel her to follow the treatment recommendations. Documentation should include how, when, and what information was provided to the patient and family regarding the significant risks to both the patient and the unborn child if the recommended care were not provided. If time permits, the treatment options should be reevaluated with the patient at frequent intervals, with detailed documentation in the patient’s medical record. Additionally, legal counsel for the health care providers and medical facility may wish to prepare an “assumption of risk” form for the patient (and, if possible, her husband) to sign. This form represents another level of documentation (beyond the detailed notes in the patient’s medical record) demonstrating that the patient was fully informed about the risks associated with her refusal of treatment and that she voluntarily elected to accept those risks. However, such a release signed by the parents may not protect the physician and medical facility from a claim brought on behalf of the child who suffers an injury as a result of nonintervention. In some cases the court has found that physicians have a duty to provide care to the unborn child.70

Patient “assumption of risk” does not release a health care provider from his or her obligations to provide other treatment within the accepted standard of care. For example, in Shorter v. Drury,71 a case that involved a patient’s refusal of blood transfusion because of religious preferences, the court upheld the validity of an “assumption of risk” (i.e., release) that relieved the physician from liability for compliance with the patient’s refusal of blood transfusion before and after surgery but nonetheless held him partially responsible for her death because of his negligent performance of the surgery.71

Before deciding whether to seek court review, health care providers should identify what issue they want the court to resolve. Is it whether the pregnant woman is competent? Is it whether there is a superior state interest in preserving the life of the viable fetus and/or the pregnant woman despite the (competent) patient’s desire to refuse recommended care? Health care providers also should consider whether a court is the proper forum for resolving those issues or whether another forum (e.g., an institutional ethics committee) may be a better choice. If a patient care dilemma is put before a judge, the health care providers give up a large amount of control over the disposition of the case. Nonetheless, if a patient’s competency is at issue and there is adequate time, court review to settle the patient’s competency may be beneficial and is supported by both the ACOG guidelines54 and the In re: A.C. decision.58 It is beneficial to obtain authorization for the provision of medically recommended care without waiting until the situation becomes an emergency. If the patient is deemed incompetent, the court may either appoint a surrogate decision-maker or directly authorize (by court order) the provision of medically indicated care.

It is not unusual for physicians to disagree with their patients’ health care decisions, and such differences are expected. In some cases, physicians conclude that providing the requested care would present a personal moral problem—a conflict of conscience, which prompts them to refuse to provide the requested care. Conscientious refusals have become especially prevalent in the practice of reproductive medicine, an area characterized by deep societal divisions regarding the morality of contraception and pregnancy termination. The ACOG Committee on Ethics72 has acknowledged that “respect for conscience is one of many values important to the ethical practice of reproductive medicine.” The ACOG stated that when conscience implores physicians to refuse to perform abortion, sterilization, and/or provision of contraceptives, “they must provide potential patients with accurate and prior notice of their personal moral commitments.” The ACOG committee opinion also emphasized that providers have an obligation to provide medically indicated care in an emergency that threatens the patient’s health, in which referral is not possible.72

Disclosure of Unanticipated Outcomes and Medical Errors

In 1999, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) estimated that preventable medical errors in the hospital setting kill 44,000 to 98,000 patients each year.73 In December 2006, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) initiated the 5 Million Lives Campaign.74 At that time, the IHI estimated that 15 million incidents of harm occurred in U.S. hospitals each year (40,000 per day). Since that time, the prevalence of medical errors remains unacceptably high and continues to draw the focus of the public, regulators, and health care providers.75 Large-scale efforts are underway to improve the safety in health care, and many organizations have achieved remarkable improvements.76

Most practitioners strive to provide the highest quality of care, but even with the growing focus on patient safety, unintended consequences—including patient injury and death—do occur. Unfortunately, most physicians remain largely unprepared to engage patients and their families in a timely, truthful, and candid manner in the aftermath of such events. In 1984, David Hilfiker wrote candidly of a life-altering mistake that he had made as a family physician treating a young woman in a small town in Minnesota.77 Hilfiker was caring for a young woman named Barb Daily whom they both believed to be pregnant. He had delivered Barb and Russ Daily’s first child, Heather, 2 years earlier, and he had been a friend of the couple for some years. After several months of care, her serial urine pregnancy test results remained negative and her uterus was only slightly enlarged. Concluding that she may have experienced a missed abortion, Hilfiker scheduled her for a dilation and curettage. The procedure was performed, but it became apparent that the diagnosis was incorrect and the procedure had been carried out with a live fetus. In his reflections on the event, Hilfiker wrote of a physician’s expectations of perfection, the lack of training in dealing with unexpected outcomes and mistakes, and the damaging effects of these conditions on physicians.77

Disclosure of errors and unanticipated outcomes is a key component in the national patient safety movement. It is also an ethical mandate and a regulatory requirement. The ethical imperative is captured in the following passage from the Charter on Medical Professionalism, published by the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation78:

Physicians should also acknowledge that in health care, medical errors that injure patients do sometimes occur. Whenever patients are injured as a consequence of medical care, patients should be informed promptly because failure to do so seriously compromises patient and societal trust. Reporting and analyzing medical mistakes provide the basis for appropriate prevention and improvement strategies and for appropriate compensation for injured parties.

The AMA’s Code of Medical Ethics contains the following statement: “It is a fundamental ethical requirement that a physician should at all times deal honestly and openly with patients…. Concern regarding legal liability, which might result following truthful disclosure, should not affect the physician’s honesty with a patient.”79 The Joint Commission standard RI.2.90 requires that “patients and, when appropriate, their families, are informed about the outcomes of care, treatment, and services that have been provided, including unanticipated outcomes.”80 Many states require reporting of medical errors, and some have legislated “apology” laws that encourage practitioners to be empathetic and honest with patients by allowing certain statements of sympathy to be made without fear of admitting medical liability.81

Physicians and other health care providers should undergo disclosure training to help them provide prompt and honest communication with patients and families and to help manage the risks of legal liability. Many untoward outcomes do not represent malpractice; they may simply reflect risks or complications of procedures that may or may not have been adequately discussed with patients and their families before the procedure or treatment. Adequate informed consent is an essential element of an effective disclosure program. Iatrogenic injuries, obvious mistakes, wrong-site surgeries, medication errors, and similar events that harm the patient should clearly be disclosed. A failure to disclose such an error may lead the patient (or the attorney) to conclude that health care providers made a deliberate effort to “cover up” the error. Furthermore, nondisclosure after such an event can lead to a charge of fraud. In most situations in which a provider conceals an error, the law provides that the statute of limitations “clock” for filing a malpractice claim does not begin to run until the fraudulent concealment is discovered.

In 2006, the Harvard teaching hospitals and their associated Risk Management Foundation developed a document entitled, “When Things Go Wrong: Responding to Adverse Events.”82 This white paper acknowledged the presence of many barriers to disclosure, including the fear of being sued, but the authors insisted that communication with patients and their families must be timely, open, and ongoing. In addition to stressing the imperative of providing support for the patient and/or family involved in the unexpected outcome, the paper emphasized the need to provide support to the health care providers involved. This concern is reflected in a 2008 survey that indicated that as many as 75% of obstetricians felt that caring for a patient with a stillbirth exacted a large toll on them, with almost 10% of those affected considering giving up their obstetric practice.83

Organizations that have adopted robust disclosure policies often have early settlement or “offer” programs, with the goals of reducing the overall costs of claims and speeding the resolution process. Recognizing the long-standing gridlock over tort reform, this and other approaches may provide a better balance between the interests of health care providers and their patients. Not only is it an opportunity to reform the process of compensating those who may have been injured, but it can also be linked to improvements in patient safety. A distinguishing feature of “disclosure and offer” models is that information and insights generated from the investigative process can be shared and analyzed for the purposes of implementing interventions that improve patient safety.84 Physicians have a unique opportunity to lead such efforts, and their participation promotes the buy-in of other staff members.

Contemporary Risk Management Strategies

Prevention of medical errors and adverse outcomes frequently focuses on the safety culture of the organization, communication and teamwork, and the intelligent use of protocols and checklists (see Chapter 11). The concept of a safety culture originated in organizations outside of health care sometimes referred to as high reliability organizations (e.g., nuclear industry, aircraft carrier operations).85 A culture of safety is characterized by an institution-wide commitment to minimize adverse events despite the performance of intrinsically complex and hazardous work.86 The key features of a “culture of safety” are:

Safety culture has been defined and can be measured; poor safety culture has been linked to increased error rates and adverse outcomes. Achieving a culture of safety in health care is daunting, because a culture of individual blame remains dominant and traditional. An issue that often arises is balancing the twin concepts of “no blame” and appropriate accountability. This is a particular struggle with physicians, given that few organizations have implemented meaningful systems of accountability that apply to the physicians.87

Communication and teamwork lapses are one of the primary causes of sentinel events identified by The Joint Commission from 2009 to 2011.88 A 2010 review of obstetric malpractice risks by a major insurer found that 65% of the malpractice cases involved high-severity injuries, including maternal and infant deaths.89 The most frequent contributing factors were substandard clinical judgment (77% of claims) and miscommunication (36% of claims). The report specifically noted that “at the intersection of individual decision making and team communication, teamwork training fosters development of a culture and structure for effective communication and decisive action. Its hallmarks—development of shared mental models, broad situational awareness, and clear communication among team members—facilitate clinicians’ ability to timely identify signs of distress and take appropriate action.”89

There is also increasing recognition of the value of smart checklists and protocols. Checklists may simplify complex procedures and make them less prone to error. Checklists may reduce the mental flaws inherent in human behavior.90 The ACOG has issued an opinion noting that “protocols and checklists have been shown to improve patient safety through standardization and communication. Standardization of practice to improve quality outcomes is an important tool in achieving the shared vision of patients and their health care providers.”91

Some health care organizations and liability insurers are now adopting strategies to specifically promote these goals (e.g., offering financial incentives to providers for completing disclosure training, participating in multidisciplinary didactic training programs to support accurate interpretation of electronic fetal heart rate tracings, the adoption of other safe practices). Federal agencies, working with health care organizations and liability providers, are also supporting similar initiatives.92

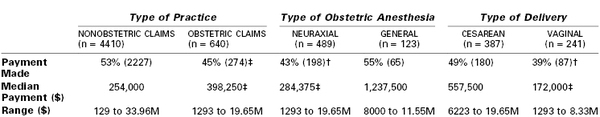

Liability Profiles in Obstetric Anesthesia: the American Society of Anesthesiologists Closed-Claims Project

In 1985 the ASA Committee on Professional Liability began an ongoing study of insurance company liability claims involving anesthesiologists. Cases that are closed (i.e., no longer active) are reviewed by practicing anesthesiologists, abstracted, double-checked by the ASA Closed-Claims Committee, and entered into a computer database. In 1991 and 1996 comprehensive analyses of obstetric anesthesia claims were published, based on a total database of 1541 and 3533 claims, respectively.93,94 In 2009, another publication compared obstetric claims from 1990 to 2003 with those before 1990.95 As of December 2010, some 9536 claims (excluding those for dental injuries) from more than 35 insurance companies across the country have been reviewed and entered into the ASA Closed-Claims Project database. The analysis reported in this chapter focuses specifically on the 640 obstetric claims in the ASA Closed-Claims Project database between 1990 and 2010.

It is important to recognize the limitations of this kind of study. A closed-claims study cannot determine the incidence of a complication, for a number of reasons. First, the denominator is unknown. Neither the total number of anesthetics given each year in each category nor the actual number of injuries per year is known. Second, not all injuries result in a claim of malpractice, and the anesthesiologist may not be named in a claim resulting from an anesthesia-related injury. This latter category may comprise a significant population of patients, which may make the relationship between cause and injury impossible to construct.96 Conversely, anesthesiologists may be named in claims in which there was no anesthesia-related adverse event.

The claims that have been reviewed are not a random sample of such data. However, given the large number of participating insurance carriers, they are likely to be broadly representative of liability claims involving obstetric anesthesia care in the United States.

Despite the significant limitations of closed-claims studies, such efforts do provide information that cannot be obtained in other ways. For example, claims involving obstetric anesthesia care can be compared with those from other types of anesthesia practice to determine whether different patterns of injury and outcome emerge. We can ask such questions as: What injuries are most common in obstetric anesthesia claims? What is the relationship between the type of anesthesia and the presumed injury? What are the precipitating events that lead to the injuries? How do payment rates compare between obstetric and nonobstetric claims?

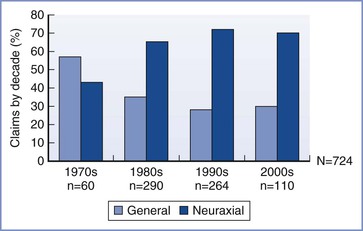

Approximately 12% of the 9536 claims in the ASA Closed-Claims Project database involve anesthesia care for patients undergoing vaginal or cesarean delivery. Of these obstetric claims, 66% involve cesarean delivery. The anesthesia workforce surveys conducted in 1981, 1992, and 2001 revealed a significant increase in the proportion of cesarean deliveries performed under neuraxial anesthesia and a corresponding decrease in those performed with general anesthesia.97 An analysis of the ASA Closed-Claims Project database illustrates a similar trend in the claims for cases involving neuraxial and general anesthesia for cesarean delivery (Figure 33-1).

FIGURE 33-1 The percentage of claims in which the anesthetic technique for cesarean delivery was either neuraxial or general. Data are shown as the percentage of the total number of claims for the indicated decade. (Data from the ASA Closed-Claims Project database, N = 9536, December 2010.)

Anesthesia-Related Injuries

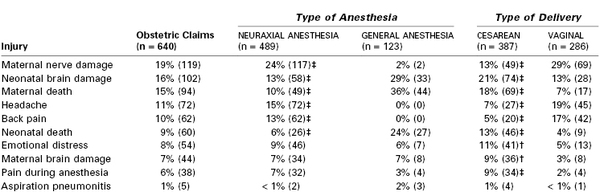

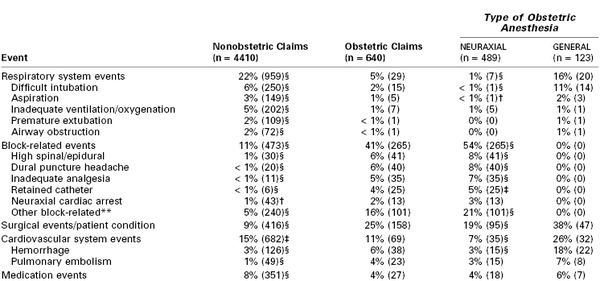

Table 33-1 lists all injuries or complications that had a frequency of 3% or greater in the obstetric claims that occurred in 1990 or later, as well as the type of anesthesia that resulted in the injury. Maternal nerve damage and neonatal brain damage were the most common injuries. In contrast to previous analyses, the proportion of nerve damage claims is now greater than maternal death claims. This finding likely reflects the increased use of neuraxial anesthesia (with a corresponding decrease in the use of general anesthesia) in obstetric anesthesia practice over the past two decades. A significantly greater proportion of nerve damage claims were associated with vaginal delivery compared with cesarean delivery. Although nerve damage in obstetric patients is more likely secondary to obstetric causes (e.g., vaginal delivery, fetal position during pelvic descent, maternal position during the second stage of labor [see Chapter 32]) than directly attributable to neuraxial anesthesia, the obstetric claims analysis published in 2009 found that nearly two thirds of the nerve damage claims may be directly linked to a neuraxial procedure.95 Unfortunately, in many cases it is almost impossible to differentiate between an anesthetic or obstetric cause for the nerve injury; appropriate neurologic consultation and investigation improves the likelihood of a correct diagnosis in these patients.

TABLE 33-1

Most Common Injuries in Obstetric Anesthesia Claims*

* The most common injuries in the obstetric group of claims that occurred in 1990 or later are shown as % (n). Percentages are based on the total claims in each group. Some claims indicated more than one injury and are represented more than once. Claims involving brain damage include only patients who were alive when the claim was closed. Claims for which type of anesthesia or form of delivery were unknown are excluded.

† P ≤ .01;

‡ P < .001 compared with general anesthesia or vaginal delivery.

Data from the American Society of Anesthesiologists Closed-Claims Project database, N = 9536, December 2010.