Mediastinal Disease

Anatomic Features

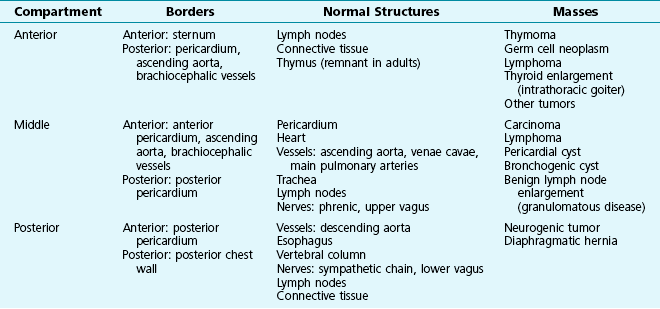

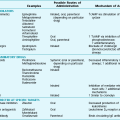

The mediastinum is bounded superiorly by bony structures of the thoracic inlet and inferiorly by the diaphragm. Laterally, the mediastinal pleura on each side serves as a membrane separating the medial aspect of the lung (with its visceral pleura) from the structures contained within the mediastinum. The mediastinum most frequently is divided into three anatomic compartments: anterior, middle, and posterior (Table 16-1). This division is particularly useful for characterizing mediastinal masses because specific etiologic factors often have a predilection for a particular compartment. Normal structures located within or coursing through each of the compartments may serve as the origin of a mediastinal mass. Consequently, knowledge of the structures contained in each of the three compartments is important for the clinician in evaluating a patient with a mediastinal mass.

The borders of the three mediastinal compartments are visualized most easily on a lateral chest radiograph (Fig. 16-1). Several descriptions exist for the limits defining each compartment. According to the scheme used here, the anterior mediastinum extends from the sternum to the anterior border of the pericardium. Included within this region are the thymus, lymph nodes, and loose connective tissue.

Mediastinal Masses

Because of the predilection for certain types of masses to occur in specific mediastinal compartments, it is easiest to separately consider masses occurring in each of the three anatomic regions. However, a fair amount of overlap occurs; that is, many types of mediastinal masses are not exclusively limited to the one compartment where they most frequently appear. A summary of the types of mediastinal masses, arranged by anatomic compartment, is given in Table 16-1.

Diagnostic Approach

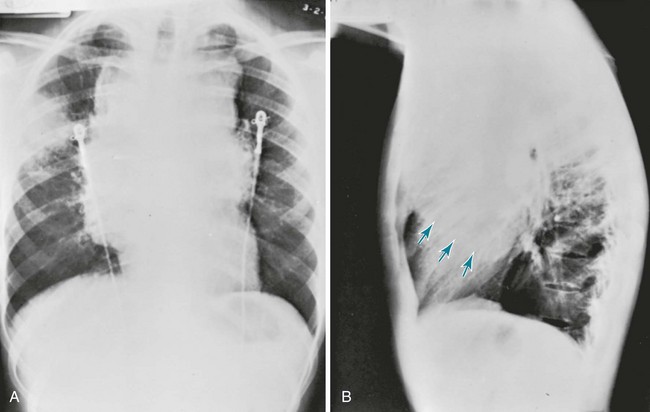

In almost all cases, the initial diagnostic test is the chest radiograph, which generally shows the mass and allows determination of its location within the mediastinum (Fig. 16-2). The mass can be further characterized by a variety of other techniques, but CT is generally the most valuable. The CT scan is particularly useful for defining the cross-sectional appearance of the lesion, its density, and its relationship to other structures within the mediastinum. With magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), blood vessels can be distinguished from other mediastinal structures without the use of radiographic contrast. Unlike the traditional presentation of CT images as axial views, MRI can display images in coronal and sagittal planes as well as cross-sectional axial views. 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography yields information on tissue metabolism, which is generally increased in active neoplastic or infectious processes.

Pneumomediastinum

Pathophysiology

With accumulation of air in the mediastinum, an increase in pressure would be expected to cause a decrease in venous return to the great veins, with resulting cardiovascular compromise. However, when pressure builds up within the mediastinum, air usually dissects further along fascial planes into the neck, allowing release of the pressure and preventing disastrous cardiovascular complications. In addition, an increase in mediastinal pressure sometimes results in rupture of the mediastinal pleura and escape of air into the pleural space, with consequent development of a pneumothorax (see Chapter 15).

Diagnostic Approach

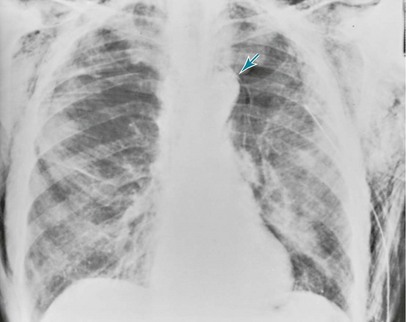

The chest radiograph and chest CT scan are the most important studies for documenting a pneumomediastinum. Gas may be seen within the mediastinal tissues and usually is visible as one or more radiolucent stripes alongside and parallel to the heart border or aorta (Fig. 16-3).

Caceres, M, Ali, SZ, Braud, R, et al. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: a comparative study and review of the literature. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:962–966.

D’Andrilli, A, Venuta, F, Rendina, EA. Surgical approaches for invasive tumors of the anterior mediastinum. Thorac Surg Clin. 2010;20:265–284.

Detterbeck, FC. Evaluation and treatment of stage I and II thymoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5(10 Suppl 4):S318–S322.

Detterbeck, FC, Parsons, AM. Thymic tumors. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:1860–1869.

Duwe, BV, Sterman, DH, Musani, AI. Tumors of the mediastinum. Chest. 2005;128:2893–2909.

Laurent, F, Latrabe, V, Lecesne, R, et al. Mediastinal masses: diagnostic approach. Eur Radiol. 1998;8:1148–1159.

Lin, JC, Hazelrigg, SR, Landreneau, RJ. Video-assisted thoracic surgery for disease within the mediastinum. Surg Clin North Am. 2000;80:1511–1533.

Maunder, RJ, Pierson, DJ, Hudson, LD. Subcutaneous and mediastinal emphysema: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Arch Intern Med. 1984;144:1447–1453.

Ribet, ME, Cardot, GR. Neurogenic tumors of the thorax. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;58:1091–1095.

Ribet, ME, Copin, MC, Gosselin, B. Bronchogenic cysts of the mediastinum. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;109:1003–1010.

Strollo, DC, Rosado de Christenson, ML, Jett, JR. Primary mediastinal tumors. Part 1. Tumors of the anterior mediastinum. Chest. 1997;112:511–522.

Strollo, DC, Rosado de Christenson, ML, Jett, JR. Primary mediastinal tumors. Part 2. Tumors of the middle and posterior mediastinum. Chest. 1997;112:1344–1357.

Takada, K, Matsumoto, S, Hiramatsu, T, et al. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: an algorithm for diagnosis and management. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2009;3:301–307.

Takahashi, K, Al-Janabi, NJ. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of mediastinal tumors. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;32:1325–1339.