Management of Amputations

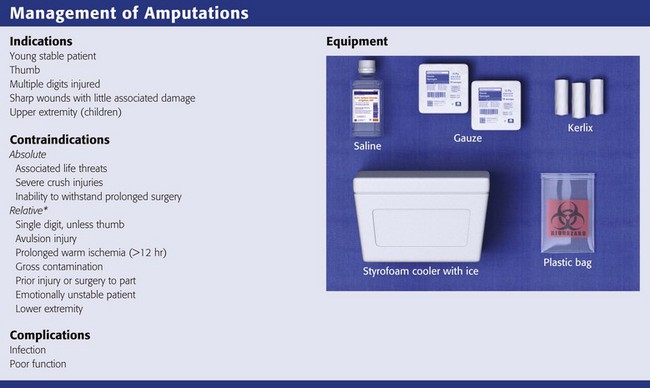

Review Box 47-1 Management of amputations: indications for reimplantation, contraindications, complications, and equipment.

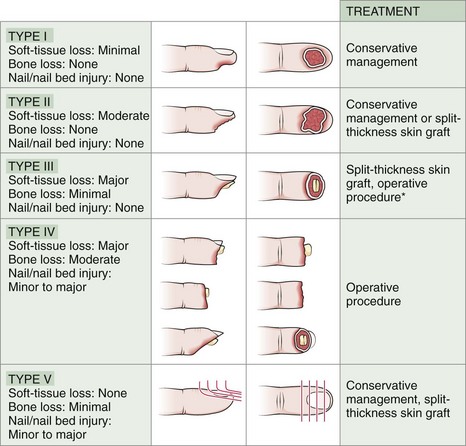

*If the victim is a child or if there are multiple losses, salvage reimplantations are attempted and the relative contraindications are ignored.

“The first person caring for an injured hand will probably determine the ultimate stage of its usefulness.”1 Consequently, rapid and appropriate emergency care of a patient with an amputated part is crucial to the salvage and preservation of function. This chapter discusses the acute care of amputated parts before they are replanted and specifically addresses the management of distal digit amputations and dermal “slice” wounds.

The peak incidence of traumatic amputations occurs between the ages of 20 and 40 years.2,3 Men predominate over women at a ratio of 4 : 1. Local crush injuries are the most common mechanism of injury, and sharp guillotine amputations are the least common.4,5 Partial amputations occur as often as total amputations.6 Proximal amputations are less common than distal amputations.

The media has somewhat exaggerated the success of replantation and has often generated unrealistic expectations from the public. The technical limitations of successful repair of vessels that are less than 0.3 mm in diameter usually preclude replantation of digits distal to the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint.7 Successful revascularization of amputated parts often ensures viability, but neurologic, osseous, and tendinous healing is critical for ultimate function. If there is incomplete neurologic recovery, limited range of motion, and intolerance to cold, the replanted part may have little functional value for the patient. Rehabilitation from replantation surgery may be prolonged, with more than 1 year often required, as well as repeated surgical procedures. The emergency clinician should be aware of the limitations of replantation surgery and should not encourage unrealistic expectations in injured patients or their families.8

Background

The possibility of restoring viability and function to traumatically severed parts has fascinated clinicians for centuries. Clinicians have attempted to replant parts with little more than a few sutures and secure bandaging and have occasionally had spectacular results. One of the earliest medical reports was by Fioravanti,9 who in 1570 reported successful replantation of a soldier’s nose that had been severed by a saber. He first cleansed it with urine and then carefully bandaged it. In 1814, Balfour10 reported successful replantation of a finger that was severed with a hatchet by using only meticulous alignment and secure bandaging.

The ability to consistently replant amputated parts awaited the development of modern microvascular surgical techniques. The first reported successful upper limb replantation was by Malt and McKhann in 1962.11 Later that year, Chen and Pao12 reported successful replantation of a hand and arm. Developments in microsurgical techniques, advanced optics, and microsurgical instruments have created the ability to consistently replant amputated parts with a high degree of success. Since 1965, when Kleinert and Kasdan13 reported the first successful microvascular anastomosis of a digital vessel, several large series of replantations have reported success rates ranging from 70% to 90%.5,6,14–20 To the original pioneers in replant surgery, survival of the replanted tissue was the criterion for success, but with further technological and surgical refinements, today’s surgeons emphasize functional recovery as well as viability. Replantation of a part that is painful or useless or that interferes with function is a disservice to the patient and is less desirable than early restoration of function without replantation.21,22

Indications

Preservation of the amputated part is generally indicated whenever there is a potential for replantation or revascularization. Revascularization and reanastomosis of partially and completely amputated parts should be provided when there is hope of preservation or restoration of function. Aesthetic considerations, patient avocations, and occasionally the patient’s religious or social customs may also influence the decision to proceed with surgery.21,23,24 In the end, the microsurgical team and patient must reach the decision together after a rational explanation of the potential results and successes.

Indications for replantation of fingers and hands have been proposed and are generally accepted, although they should not be applied rigidly in all circumstances. Successful functional recovery is more likely with distal than with proximal extremity amputations and more likely with multidigit amputations, single-digit thumb amputations, or transmetacarpal amputations.25 Generally, these are the indications for replantation (Review Box 47-1). Single-digit amputations that are both proximal to the DIP joint and distal to the flexor digitorum superficialis may be replanted successfully with good functional recovery (Fig. 47-1).

Successful replantations have been reported in patients from the ages of 7 months to 84 years.26,27 There are no fixed age limits for replantation, although particularly good functional results have been reported in children because of their regenerative capacity and adaptability to rehabilitation.2,28,29 The decision to replant is made on a case-by-case basis by the microsurgical team, who must weigh all the factors involved.

Contraindications

There is no contraindication to managing the amputated part and stump as though replantation were going to occur, even when replantation is considered unlikely. In addition, ancillary personnel can often handle care of the amputated part and stump during resuscitation and transportation of the patient. However, it must be remembered that evaluation and treatment of life-threatening injuries always take precedence over care of the amputated part. Contraindications to replantation are listed in Review Box 47-1 and are discussed in the following sections. Note that even when replantation is contraindicated, tissue (skin, bone, tendon) from the amputated part may be useful in restoring function to other damaged parts. Never discard amputated tissue until all possible uses of the severed parts are considered. For example, even an amputated fingertip not suitable for replantation may be an ideal donor source for a skin graft on the stump.

General Considerations

Severe extremity trauma is a significant cause of morbidity, and the potential for successful replantation in terms of survival, as well as useful function, is directly related to the mechanism of injury. Guillotine-type injuries are the least common but have the best prognosis because of the limited area of destruction. Crush injuries are the most common but produce more tissue injury and therefore have a poorer prognosis. Avulsion injuries have the worst prognosis because a significant amount of vascular, nerve, tendon, and soft tissue injury invariably occurs.2,4–6,30

Ischemia Time

The time that an amputated part can survive before replantation has not been determined. After 6 hours, additional delay may decrease the success rate of revascularization and lead to diminished function. Skin, bone, tendons, and ligaments tolerate ischemia much better than do muscle and connective tissue. As a general rule, the more proximal the amputation, the less ischemia time that the amputated part can tolerate. Attempts to extend viability during ischemia have shown that the most important controllable factor is the temperature of the amputated part. Warm ischemia may be tolerated for 6 to 8 hours.31 When the part is cooled properly to 4°C, 12 to 24 hours of ischemia may be tolerated with distal amputations.2,4,6,14,15,32 There is a report of successful digital replantation after 33 hours of cold ischemia.33 Hypothermia limits the metabolic demand of tissues, thereby preserving intracellular energy and reducing the production of toxic metabolites caused by ischemia.33–36 It also retards the development of acidosis37 and may prevent the no-reflow phenomenon that can follow ischemic and low-flow states.21,33,34,38

Delay in replantation of proximal arm and leg amputations containing significant amounts of muscle tissue can lead to the buildup of toxic products. In such cases, when the blood supply is restored, the absorbed toxins have been reported to cause respiratory failure, renal failure, cardiovascular collapse, and even death.21,24,33,34,39–42

Intraoperative perfusion techniques such as those used for organ transplants to extend anoxic time are being used to help cool amputated parts before replantation. However, emergency clinicians should not attempt perfusion because the risk of damaging vessels, as well as the potential delay in care and rapid transport, overrides the theoretical benefits of cold perfusion in the emergency department (ED).21,43

Assessment of the Patient

Initiate tetanus prophylaxis and broad-spectrum systemic antibiotic therapy (e.g., cephalosporins). Intravenous opioids are usually required for pain; titrate the dose to the clinical condition. With fingertip amputations, digital or regional nerve blocks are ideal for pain relief but may make functional and neurologic evaluation by a consultant impossible (see Chapters 31 and 32). Aspirin, low-molecular-weight dextran, or both have been administered in an attempt to maintain small-vessel perfusion44 but have not proved beneficial in the ED management of these injuries.

Examination of the stump may be brief and should primarily be an assessment of the degree of damage to surrounding tissue (Fig. 47-2). Remove gross contamination by irrigating with normal saline. Do not use local antiseptics, especially hydrogen peroxide or alcohol, because they may damage viable tissue. Similarly, tissue should not be manipulated, clamped, tagged, or further traumatized in any way. Assess the degree of contamination, the level of the injury, and any concomitant injury. Examine the amputated part for the degree of tissue injury, level of contamination, and the presence of distal injuries. Obtain radiographs of the amputated part and proximal stump that include at least one joint proximal to the injury site (see Fig. 47-2B). If not already done, obtain preoperative laboratory studies and intravenous access in an uninjured extremity.

Care of the Stump and Amputated Part

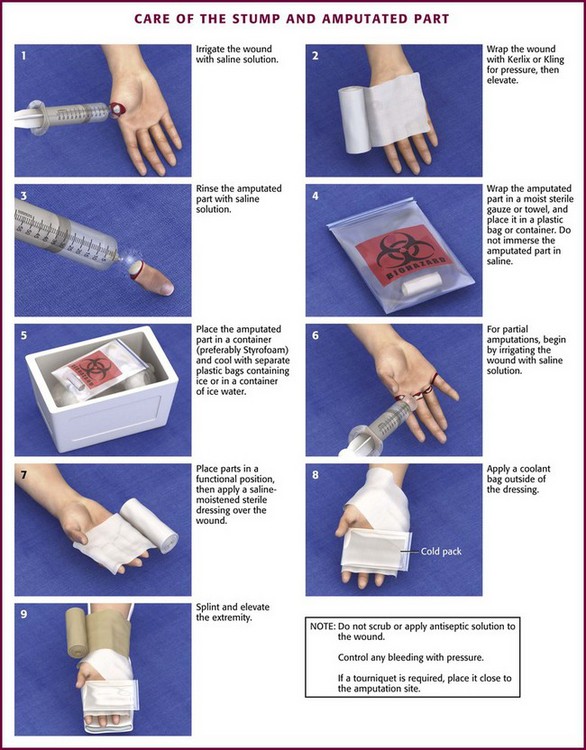

The stump should be dealt with during the secondary assessment of the trauma victim (Box 47-1). If replantation is proposed, the goals of initial care include control of hemorrhage and prevention of further injury or contamination. Remove all jewelry and irrigate the stump with normal saline to remove gross contamination; only the replantation team should perform manual débridement and dissection. Do not clamp arterial bleeders. Cover the stump wound with a saline-moistened sterile dressing to prevent further contamination and to limit damage from desiccation. Splint the stump for protection and to prevent further injury from concomitant fractures or compromised blood flow from a change in position. Splinting and elevation may also reduce swelling and help control bleeding.

Care of the amputated part follows the same general guidelines as for the stump. Remove all jewelry and irrigate the amputated part with normal saline to remove gross contamination. Wrap the amputated part in a saline-moistened sterile dressing; do not handle the part any more than necessary to prevent further damage. Avoid direct prolonged immersion in saline or hypotonic fluids because it may cause severe maceration of the tissue and make replantation technically more difficult. Cool the amputated part as soon as possible. The ideal temperature is 4°C, but care must be taken to prevent freezing of tissues. To best accomplish this, wrap the amputated part in saline-moistened gauze, place the gauze-wrapped part in a watertight plastic bag, and then immerse the bag in a container of ice water (Fig. 47-3). Do not place amputated parts directly on ice because tissue in contact with ice may freeze. A guideline is to use half water and half ice. Avoid excessive ice. Cooling coils and refrigeration devices have occasionally been used but are not generally available and offer no significant advantage. Label the tissue containers with the patient’s name, the amputated part contained within, the time of the original injury, and the time that cooling began.

Figure 47-3 Care of the stump and amputated part.

Treatment of partial amputations with vascular compromise is the same as that just described. Irrigate the wound with normal saline. Place a saline-moistened sponge on the open tissue, and wrap the injury in a sterile dressing in which a splint has been incorporated to protect it from further injury. Place ice packs or commercial cold packs over the dressing to cool the devascularized area (see Fig. 47-3, step 6).

Special Considerations

Determine hand function in part by testing pinch and grasp functions. If the index finger is amputated, the middle finger can often adequately perform the pinching function formerly provided by the index finger. Power in grasping and gripping is primarily an ulnar function of the fourth and fifth digits. An effective grip that provides the ability to hold a variety of objects is a central function of the ring and middle fingers. In addition to its function in pinching, the thumb is the major opposing force for successful grip and grasp. The thumb is the most important digit for adequate hand function, and its loss results in 40% to 50% disability. For this reason, such disability requires aggressive attempts to replant amputated thumbs. If this is impossible or unsuccessful, secondary alternatives are pollicization of other digits or toe transfers.45,46 Pollicization is a plastic surgery technique in which a thumb is created by using another finger.

Lower Extremity Amputations

There are few reports of successful replantation of amputated parts of the lower extremity.47–49 Indications for replantation of lower extremity parts are different from those of amputated upper extremity parts. Isolated toe amputations are not replanted. It is generally held that if replantation does not restore function, a patient may be substantially better off with a prosthesis because lower limb prostheses, especially those used below the knee, are well tolerated and functional.50 Prostheses provide a secure stance and permit locomotion. Lower extremity replantation generally requires skeletal shortening, and distal nerve regeneration is often imperfect, with both deficits producing dysfunction. Extracellular matrix scaffolds and muscle regeneration with stem cells are promising technologies. However, the functional limitations that result from loss of the muscle needed to cover bone and provide limb function are a major factor in the decision to amputate a salvaged limb.51,52 A patient with a replanted lower extremity with significant shortening and without sensation would function better with a prosthesis. This is not necessarily true of someone with an upper extremity replant. For these reasons, lower limbs are not generally replanted except under particularly ideal circumstances, usually in children. The final decision regarding replantation should be left to the replantation team.

Fingertip Amputations and Dermal “Slice” Wounds

Proper treatment of distal fingertip injuries is controversial, but good results are often achieved with conservative management. Fingertip amputations frequently heal by normal wound contracture, but occasionally this results in loss of the functional ability to palpate. The basic goals of treatment are to provide tissue coverage, an acceptable cosmetic result, and early functional recovery. Distal amputations with a wound area smaller than 10 mm2 are not a problem (Figs. 47-4 and 47-5). Larger dorsal wounds also heal well by secondary intention. However, when loss of skin and soft tissue from the finger pad is significant, the clinician is faced with a more challenging situation. Volar skin is unique because of its combination of toughness and sensitivity. Wounds with significant loss of volar tissue frequently require additional treatment. Children, with their regenerative capacity, often progress very well when significant volar wounds are allowed to heal primarily. For older people and for amputations that involve a more significant amount of the distal digit, a wide variety of techniques for managing the injured fingertip have been advocated, including partial-thickness skin grafts; full-thickness skin grafts; V-Y, Kutler, Kleinert, and island advancement flaps; and various local and distal flap coverage techniques. These procedures are designed to preserve length, soft tissue coverage of exposed bone, and sensation of the finger pad. Each of these procedures has its own indications, complications, and limitations.53,54 Although traditionally some type of grafting or advancement techniques have been used for distal guillotine amputations, conservative management is now more common, even if some portion of bone is exposed (Fig. 47-6). Further discussion of these procedures is beyond the scope of this chapter. Most of these techniques are best performed by a specialist in the operating room at the time of the injury or as delayed procedures when necessary.

Figure 47-4 Clinical classification of fingertip injuries and treatment of each type. *Note: Though traditionally treated with various flaps and advancement techniques, type III guillotine amputations often do well with conservative management, even if some bone is exposed (see Fig 47-5). (From Newmeyer WL. Managing fingertip injuries on an outpatient basis. J Musculoskel Med. 1985;2:17. CMP Medica. All rights reserved.)

Incomplete transections and small distal amputations without significant soft tissue loss may heal well with conservative therapy started by the emergency clinician. Nonoperative treatment in selected patients provides excellent functional and cosmetic results, minimizes recovery time, and has few complications.54–60 Children have excellent regenerative capacity and also respond extremely well to conservative treatment. Débride necrotic and grossly contaminated tissue. Irrigate the wound thoroughly with normal saline. If bone is left exposed without soft tissue coverage, the patient will probably need an operative procedure. Alternatively, the bone may be rongeured (shortened) to allow soft tissue coverage and primary healing with better functional recovery. The nail bed tissues should be preserved, if possible, because the presence of a nail affects the cosmetic appearance. After cleansing and careful débridement, apply an occlusive dressing directly over the wound and then bandage and splint the finger for protection. Provide tetanus prophylaxis if needed. Amputations that involve the distal phalanx are frequently treated as contaminated open fractures. In these cases, a recent Cochrane review supports the early use of antibiotics to reduce the incidence of infection.61 Wounds managed conservatively must undergo serial dressing changes and cleansing. This helps provide superficial débridement, which may aid healing and minimize the chance of secondary infection. Wound contraction and healing usually result in acceptable cosmetic and functional recovery in 2 to 3 weeks. Arrange appropriate follow-up to ensure adequate healing and recovery.

Manage dermal “slice” wounds (see Figs. 47-4 type I and 47-5) by gently cleansing the wound and applying antibiotic ointment and a nonadherent dressing, followed by a pressure dressing. The patient should return in 48 to 72 hours for the wound to be inspected and the dressing changed. At that time, instruct the patient on the use of nonadherent dressings and to change them daily for 10 to 14 days until functional epithelialization of the wound takes place. A protective finger splint or guard also minimizes the risk for further injury and pain from trauma to the sensitive wound area. Protection allows earlier return to functional use and employment. Wounds larger than 10 mm2 and those with deep loss of digit pulp tissue may be candidates for skin grafting.

Conservative Management of Fingertip Amputations

An amputation of the fingertip that does not involve significant injury to bone or massive tissue maceration generally does well with conservative treatment. In the past, skin grafts, flaps, and advancement techniques were used for the type II and type III injuries depicted in Figure 47-4, but currently, such interventions are uncommon for simple fingertip amputations. The common transverse guillotine amputation from machinery heals with good cosmesis and adequate sensation, but 6 to 8 weeks may be required for complete healing. Such injuries may simply be cleaned and bandaged in the ED and appropriately referred. However, if ED follow-up is available, patients may be reevaluated and the wound selectively débrided at 1-week intervals. Figure 47-6 outlines such a conservative course.

Penis, Ear, and Nose Amputations

Penile amputations are an uncommon problem. Most cases result from self-inflicted trauma in patients who are severely psychologically disturbed. Successful replantation with microsurgical techniques has been reported. Preservation or reconstruction of the urethra to maintain a competent urinary stream is critical for success.62,63 Ears and noses are frequently partially amputated and occasionally totally amputated. Whenever possible, these body parts should be replanted unless they are severely traumatized and gross contamination is present. These wounds frequently heal well, and patients with such wounds have a high tissue survival rate and a low incidence of total necrosis. Replantation of these parts requires good suture technique and careful placement but does not necessarily require skill in microsurgical techniques.63–66

Complications

Despite optimal initial care, replantation itself may be associated with acute or long-term complications. There is the usual risk associated with anesthesia and protracted surgery. Moreover, it is not unusual for patients to need second and third emergency operations to reestablish adequate blood flow. Postoperative complications include vascular thrombosis, hemorrhage, infection, and reaction to accumulated toxins.67 Toxins accumulate in the ischemic amputated parts despite cooling. The amount of toxin is directly proportional to the amount of muscle mass and the duration of ischemia. Significant pulmonary failure, electrolyte disturbance, and even death have been reported in replantation efforts. Finally, anticoagulants are often prescribed, which creates additional risk.

References

1. Rabel, RM, Kleinert, HE. Restoration of the Hand. Indianapolis: Charles C Thomas; 1973. [19].

2. May, JW, Gallico, GG. Upper extremity replantation. Curr Probl Surg. 1980;17:634.

3. Tamai, S. Digit replantation: analysis of 163 replantations in an 11-year period. Clin Plast Surg. 1978;5:195.

4. Morrison, WA, O’Brien, BM, MacLeod, AM. Evaluation of digital replantation—a review of 100 cases. Orthop Clin North Am. 1977;8:295.

5. Weiland, AJ, Villarreal-Rios, A, Kleinert, HE, et al. Replantation of digits and hands: analysis of surgical techniques and the final results in 71 patients with 86 replantations. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1977;2:1.

6. Kleinert, HE, Juhala, CA, Tsai, TM, et al. Digital replantation—selection techniques and results. Orthop Clin North Am. 1977;8:309.

7. Kleinert, HE, Tsai, TM. Microvascular repair in replantation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1978;133:205.

8. Pinzur, MS, Gottscalk, F, Pinto, MA, et al. Controversies in lower extremity amputation. Instruct Course Lect. 2008;57:663.

9. Fiorvanti, L. In Tesoro della vita Humana. Venetia, Italia: Apresso gli heredi di M. Sessa; 1570.

10. Balfour, W. Two cases, with observations, demonstrative of the powers of nature to reunite parts which have been, by accident, totally separated from the animal system. Edinb Med Surg J. 1814;10:421.

11. Malt, RA, McKhann, CE. Replantation of several arms. JAMA. 1964;189:716.

12. Chen, CW, Pao, YS. Salvage of the forearm following complete traumatic amputation: report of a case. Clin Med J. 1963;82:633.

13. Kleinert, HE, Kasdan, MFL. Anastomoses of digital vessels. J Ky Med Assoc. 1965;63:106.

14. May, JW, Jr., Toth, BA, Gardner, M. Digital replantation distal to the proximal interphalangeal joint. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1982;7:161.

15. O’Brien, BM. Replantation and reconstructive microvascular surgery. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1976;58:87.

16. Schlenker, JD, Kleinert, HE, Tsai, TM. Methods and results of replantation following traumatic amputation of the thumb in 64 patients. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1980;5:63.

17. Kleinert, HE, Jablon, M, Tsai, TM. An overview of replantation and results of 347 replants in 245 patients. J Trauma. 1980;20:390.

18. Yoshizu, I, Katsumi, M, Tajima, T. Replantation of untidily amputated finger, hand, and arm. J Trauma. 1978;18:194.

19. Zhong-Wei, C, Meyer, VE, Kleinert, HE, et al. Present indications and contraindications for replantation as reflected by long-term functional results. Orthop Clin North Am. 1981;12:849.

20. Beris, AE, Soucacos, PN, Malizos, KN. Microsurgery in children. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;314:112.

21. Pederson, WC. Replantation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:823.

22. Mavroforou, A, Koutsais, S, Fafoulakis, F, et al. The evolution of lower limb amputation through the ages. Int Angiol. 2007;26:385.

23. Beasley, RW. General considerations in managing upper limb amputations. Orthop Clin North Am. 1981;12:743.

24. Wilson, CS, Alpert, BS, Buncke, HJ, et al. Replantation of the upper extremity. Clin Plast Surg. 1983;10:85.

25. McGee, DL, Dalsey, W. The mangled extremity. Compartment syndrome and amputations. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1992;10:783.

26. Leung, PC. Hand replantation in an 83-year-old woman—the oldest replantation? Plast Reconstr Surg. 1979;64:416.

27. Gaul, JS, Nunley, JA. Microvascular replantation in a seven month old girl: a case report. Microsurgery. 1988;9:204.

28. Kim, JY, Brown, RJ, Jones, NF. Pediatric upper extremity replantation. Clin Plast Surg. 2005;32:1.

29. Jaegar, SH, Tsai, TM, Kleinert, HE. Upper extremity replantation in children. Orthop Clin North Am. 1981;12:897.

30. Chuang, DC, Lai, JB, Cheng, SL, et al. Traction avulsion amputation of the major upper limb: a proposed new classification, guidelines for acute management, and strategies for secondary reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:1624.

31. Berger, A, Millesi, H, Mandl, H, et al. Replantation and revascularization of amputated parts of extremities: a three-year report from the Viennese replantation team. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1978;133:212.

32. Morrison, WA, O’Brien, BM, MacLeod, AM. Digital replantation and revascularization: a long-term review of 100 cases. Hand. 1978;10:125.

33. Shah, M, Kulkarni, J, Shelley, M, et al. Refrigeration of a “spare part”: a salvage procedure for preservation of the knee joint in a patient with multiple trauma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:1289.

34. Khalil, AA, Aziz, FA, Hall, JC. Reperfusion injury. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:1024.

35. Hayhurst, JW, O’Brien, BM, Ishida, H, et al. Experimental replantation after prolonged cooling. Hand. 1974;6:134.

36. Tsai, TM, Jupiter, JB, Serratoni, F, et al. The effect of hypothermia and tissue perfusion on extended myocutaneous flap viability. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;70:444.

37. Osterman, AL, Heppenstall, RB, Sapega, AA, et al. Muscle ischemia and hypothermia: a bioenergetic study using 31phosphorus nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Trauma. 1984;24:811.

38. May, JW, Chait, LA, O’Brien, BM, et al. The no-reflow phenomenon in experimental free flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1978;61:256.

39. Michalko, KB, Bentz, ML. Digital replantation in children. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:S444.

40. Matsuda, M, Shibahara, H, Kato, N. Long-term results of replantation of 10 upper extremities. World J Surg. 1978;2:603.

41. Tamai, S, Hori, Y, Tatsumi, Y, et al. Major limb, hand, and digital replantation. World J Surg. 1979;3:17.

42. Wood, MB, Cooney, WP, 3rd. Above elbow limb replantation: functional results. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1986;11:682.

43. Pereira, C, Oudit, D, McGrouther, DA. Policy for handling of amputation parts in accident and emergency departments. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:346.

44. Buntic, RF, Brooks, D. Standardized protocol for artery only fingertip replantation. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2010;35:1491–1496.

45. Chung, KC. Pollicization of the index finger for traumatic thumb amputations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:2503.

46. Ishida, O, Taniguchi, Y, Sunagawa, T, et al. Pollicization of the index finger for traumatic thumb amputation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:909.

47. Jupiter, JB. Salvage replantation of lower limb amputation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;69:1.

48. Morrison, WA, O’Brien, BM, MacLeod, AM. Major limb replantation. Orthop Clin North Am. 1977;8:343.

49. Jones, NF, Shin, EK, Mostofi, A, et al. Successful replantation of the leg in a pre-ambulatory infant. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2005;21:359.

50. Highsmith, MJ, Kahle, JT, Bongiorni, DR, et al. Safety, energy efficiency, and cost efficacy of the C-leg for transfemoral amputees: a review of the literature. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2010;34:362.

51. Tintle, SM, Keeling, JJ, Shawen, SB, et al. Traumatic and trauma-related amputations. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:2852–2868.

52. Fergason, J, Keeling, JJ, Bluman, EM. Recent advances in lower extremity amputations and prosthetics for the combat injured patient. Foot Ankle Clin. 2010;15:151.

53. Illingworth, CM. Trapped fingers and amputated fingertips in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1974;9:853.

54. Massengill, JB. Pitfalls in management of fingertip injuries and hand lacerations. Prim Care. 1980;7:231.

55. Newmeyer, W. Managing fingertip injuries on an outpatient basis. J Musculoskel Med. 1985;2:17.

56. Wang, QC, Johnson, BA. Fingertip injuries. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:1961.

57. Farrell, RG, Rappaport, B. Nonoperative management of fingertip amputations. West J Med. 1985;142:385.

58. Allen, MJ. Conservative management of fingertip injuries in adults. Hand. 1980;12:257.

59. Chow, SP, Ho, E. Open treatment of fingertip injuries in adults. Hand Surg. 1982;7:470.

60. Ipsen, T, Frandsen, PA, Barfred, T. Conservative treatment of fingertip injuries. Injury. 1987;18:203.

61. Gosselin, RA, Roberts, I, Gillespie, WJ. Antibiotics for preventing infection in open limb fractures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (1):2004. [CD003764].

62. Becker, M, Hofner, K, Lassner, F, et al. Replantation of the complete external genitals. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99:1165.

63. Strauch, B, Sharzer, LA, Petro, J, et al. Replantation of amputated parts of the penis, nose, ear, and scalp. Clin Plast Surg. 1983;10:115.

64. Grabb, WC, Dingman, RO. The fate of amputated tissues of the head and neck following replacement. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1972;49:28.

65. Miller, PJ, Hertler, C, Alexiades, G, et al. Replantation of the amputated nose. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124:907.

66. Buncke, HJ. Microsurgical replantation of the avulsed scalp: report of 20 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;97:1107.

67. McIntosh, J, Earnshaw, JJ. Antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of infection after major limb amputation. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;37:696.