Robotic-Assisted Major Pancreatic Resection

Historical landmarks in development of the pancreaticoduodenectomy

The first published report of a successful pancreaticoduodenectomy was published by Allen O. Whipple in 1935 [1]. Whipple reported 3 patients who underwent a 2-stage procedure with pancreatic duct ligation: one patient died in the perioperative period; another died 8 months later from cholangitis, and the last from metastases after 28 months. This initial report was followed by a series describing a single-stage procedure [2], the fundamentals of which we recognize today as the Whipple procedure. These fundamentals included (1) resection and reconstruction in one stage; (2) avoidance of cholecystoenterostomy by implantation of the bile duct into the jejunum, and (3) implantation of the pancreatic duct into the jejunum. Following the modification of pylorus preservation by Traverso and Longmire [3], the technical aspects of pancreaticoduodenectomy have remained essentially unchanged since Whipple described the procedure in 1935.

Postoperative mortality and morbidity remained significant hurdles to the widespread implementation of pancreaticoduodenectomy for many years after the initial description. Mortality rates approaching 30% were common for the next several decades. In 1968 John Howard reported a series of 41 consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies without a mortality [4]. This series was followed by improvements by John Cameron and colleagues [5] at Johns Hopkins, who standardized the technical aspects of this procedure and set the modern-day gold standard for outcomes. Attention to surgical detail combined with advances in critical care and anesthesia led to steady and dramatic improvements in postoperative outcomes following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Recent reports reproducibly demonstrate a morbidity rate of 30% to 40% with 1% to 3% mortality [6].

Recent refinements of the pancreaticoduodenectomy have focused on the implementation of minimally invasive approaches. Gagner and Pomp [7] described the first laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy in 1994, a procedure that lasted nearly 24 hours. Since then, Kendrick and Cusati [8] and Palenivelu and colleagues [9] have reported large series of minimally invasive pancreaticoduodenectomies with outcomes comparable with those of large open series. Most recently, robotic-assisted minimally invasive approaches have been described by the groups led by Gulianotti, Melvin, Zeh, and Moser [10–12].

Potential advantages of minimally invasive major pancreatic resection

Major pancreatic resection remains the final frontier of minimally invasive surgery, because of the twin technical challenges of controlling hemorrhage from major vessels and reconstructing the biliary and pancreatic ducts with acceptable morbidity (Box 1). The minimally invasive approach offers potential advantages compared with open surgery: (1) decreased incisional pain may lead to improved recovery time and decreased hospital stay; (2) improved postoperative recuperation and performance status may permit earlier initiation of adjuvant therapy in a higher percentage of patients with pancreatic cancer [13]. It is important that initial concerns regarding the oncologic equivalency of minimally invasive resection for cancer have proved to be unfounded in other malignancies such as colon and gastric cancer [12,14–16]. The third potential advantage of minimally invasive pancreatic resection applies to the group of patients with radiographically identifiable precursor lesions such as mucinous cystic neoplasms who may require prophylactic pancreatectomies to prevent the progression to pancreatic cancer. The availability of a minimally invasive approach with equivalent or superior recovery times might alter the risk/benefit ratio of pancreatectomy in favor of earlier intervention and improve patient acceptance of prophylactic surgery. Lastly, the technological progression in all of surgery is toward smaller more minimally invasive procedures. Reluctance or refusal on the part of hepatic/pancreatic/biliary tract (HPB) surgeons to explore innovations risks obsolescence.

Limitations of laparoscopic techniques for pancreaticoduodenectomy

Laparoscopic surgery has evolved significantly since its introduction in the early 1970s. Although advanced laparoscopic procedures are being performed at many centers, advanced procedures that require complicated resection and reconstruction such as pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) remain limited to a few specialized centers. A total of only 146 laparoscopic PDs were reported in the world’s literature in the first 14 years following Gagner’s description in 1994 [17]. Palanivelu and colleagues [9] presented 75 cases, and Kendrick and Cusati [8] reported 62 cases of totally laparoscopic PDs. These two series demonstrate that laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy can be performed safely with acceptable morbidity, although their results may be difficult to generalize to other centers [18]. The slow implementation of laparoscopic techniques for pancreaticoduodenectomy is likely the result of the limitations inherent to current technology, namely, 2-dimensional imaging, limited range of instrument motion, and poor surgeon ergonomics [17]. In this situation the surgical principles are altered to meet the limitations of the technology, leading to reluctance on the part of many HPB surgeons. A minimally invasive approach to pancreaticoduodenectomy that recreates well-established surgical principles would be a significant advance.

Robotic-assisted minimally invasive pancreaticoduodenectomy

Robotic-assisted minimally invasive surgery overcomes many of the shortcomings of laparoscopy, with improved 3-dimensional imaging, 540° movement of surgical instruments, and improved surgeon comfort and precision [19] (Box 2). These technological innovations allow complex resections and anastomotic reconstructions to be performed with techniques identical to open surgery. The authors present here their technical description and outcomes with robotic-assisted major pancreatic resections. This approach maintains maximal adherence to the traditional open surgical techniques with a minimally invasive approach.

Selection criteria for robotic-assisted pancreaticoduodenectomy

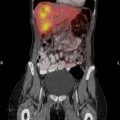

To maintain safety and transparency of surgical outcomes, all potential candidates for robotic pancreatic resection are reviewed by the Surgical Oncology Robotic Selection Committee. All robotic procedures are performed by two expert pancreatic surgeons familiar with open pancreaticoduodenectomy and capable of carrying out venous resection and reconstruction whenever indicated. Patients with periampullary malignancies who are candidates for robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy undergo individualized treatment planning based on a validated predictive model to select candidates with the highest likelihood of achieving an R0 surgical resection. The prediction rule was developed and validated in independent cohorts of patients with potentially resectable pancreatic cancer [20]. The model stratifies patients into low risk and high risk for non-R0 surgical outcomes based on findings during preoperative computed tomography (CT) and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS). High-risk patients are not offered the robotic approach and instead undergo traditional open pancreaticoduodenectomy, given the potential for robotic surgery to compromise oncologic principles in these high-risk patients. Low-risk patients are offered robotic surgery after a detailed consent process and enrollment in a prospective registry of robotic pancreatic surgery.

Technique of robotic-assisted pancreaticoduodenectomy

Step 1

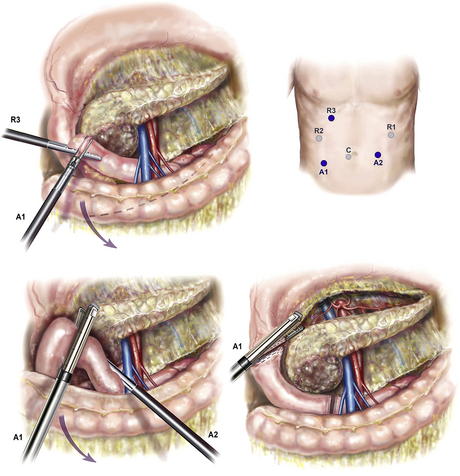

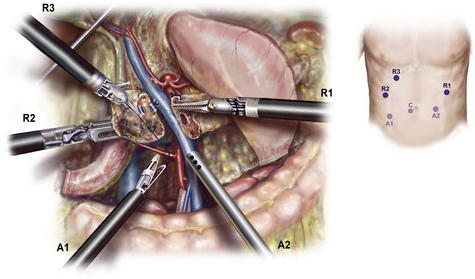

The first step involves mobilization of the right colon and exposure of the pancreatic head (Kocher maneuver). Following insufflation and laparoscopic staging to exclude unrecognized metastases (Fig. 1), the falciform ligament is sewn to the anterior abdominal wall to elevate the liver and prevent smearing of the camera. The retroperitoneal attachments of the hepatic flexure are divided, and the right colon is rotated medially down to the terminal ileum to expose the SMV at the root of the small bowel mesentery. This action is performed from the left side of the table with the LigaSure device and an atraumatic grasper (ports R1 and A2). An automated liver retractor is inserted through a 5-mm port in the far lateral right upper quadrant to expose the porta hepatis. The retroperitoneal investment of the third portion of the duodenum is divided and the pancreatic head elevated from the retroperitoneum up to the origin of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA). Next, an extended Kocher maneuver is performed from the right side of the table to release the proximal jejunum from the mesenteric vessels. The jejunum to is pulled into the right upper quadrant and is transected with a 3.5-mm linear cutting stapler approximately 10 cm distal to the former ligament of Treitz. The jejunum is marked with an Endostitch 50 to 60 cm distally to mark the duodenojejunostomy, and the jejunum is passed beneath the mesenteric vessels and the stitch located. The jejunum is then tacked to the greater curvature of the stomach to allow for easy identification during reconstruction after the Robot is docked.

Step 2: Division of the gastrocolic omentum and proximal duodenum

The gastrocolic omentum is divided in the avascular plane between the ventral and dorsal mesogatrum (see Fig. 1). The posterior stomach is mobilized from the anterior surface of the pancreas, and the left gastric vessels are identified. The groove between the gastroepiploic vascular pedicle and duodenum is opened with the LigaSure, elevating the first portion of the duodenum from the pancreatic head. The right gastric artery is clipped and divided with the LigaSure, completing the mobilization of the duodenum, which is then divided with a linear cutting stapler (port A1). The gastroepiploic pedicle is divided with a vascular stapler, preserving the vessels along the greater curve but leaving the prepyloric lymph nodes in continuity with the specimen.

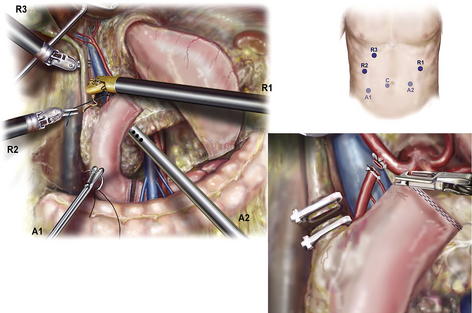

Step 4: Dissection of the porta hepatis and division of the bile duct

The common hepatic artery lymph node (station 8a) is mobilized with robotic cautery and transected with the LigaSure device to expose the superior border of the pancreas and the common hepatic artery (CHA) (Fig. 2). The CHA is followed distally into the porta hepatis to demonstrate the origin of the divided right gastric artery and trunk of the gastroduodenal artery (GDA), which is cleared of sufficient surrounding tissue to be divided safely. The PV is exposed posteriorly. A test occlusion of the GDA is performed, and flow in the CHA is verified by maintenance of visible pulsatile flow or laparoscopic B-D mode ultrasound captured in the patient console. The GDA is tied with 2-0 silk proximally and divided with a vascular stapler, ties, or 4-0 Prolene suture ligature depending on access to the porta hepatis from the assistant port. The PV is dissected into the hepatic hilum to demonstrate the medial edge of the common hepatic duct, and nodal tissue to be swept into the specimen in the process with the vessels in view. Lymph nodes along the lateral margin of the bile duct are cleared, taking care to identify aberrant right hepatic arterial anatomy. The bile duct is divided with robotic cautery scissors after a proximal Hem-o-lock clip (Teleflex, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA) is applied to prevent contamination of the peritoneum with bile. The distal margin is resected and sent for pathologic examination.

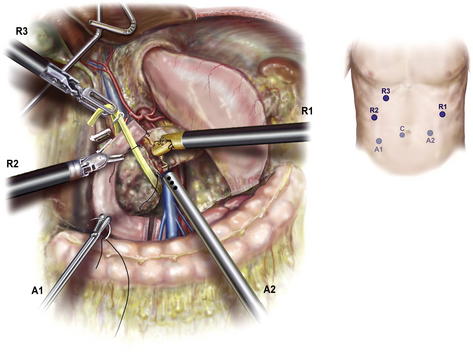

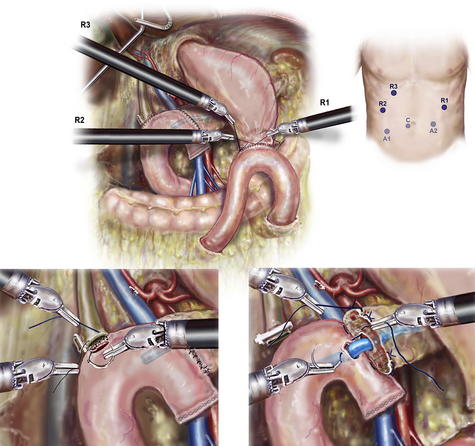

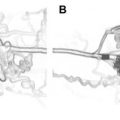

Step 5: Dissection of the pancreatic neck and mobilization of the portal vein

The origin of the right gastroepiploic vein is identified in addition to the SMV and middle colic vein (Fig. 3). These large tributary veins are either ligated or divided between 2-0 silk ties or a vascular stapler. The SMV is dissected free of the posterior surface of the pancreatic neck, and an articulated laparoscopic grasper is used to pass an umbilical tape around the pancreas. Identical to the open technique, 2-0 silk sutures are used to occlude the transverse pancreatic arteries at the inferior and superior borders of the pancreas, and the pancreas is divided with the cautery hook. The pancreatic margin is resected from the head, inked, and sent to pathology for frozen section.

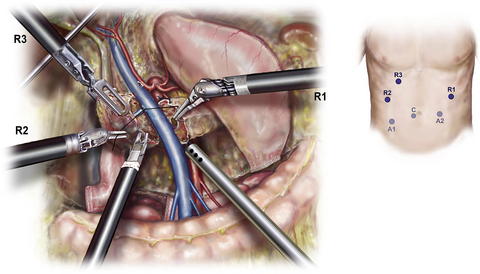

Step 6: Dissection of the retroperitoneal margin

The pancreas is elevated from the retroperitoneum with a “hanging maneuver” using the third robotic arm (R3) (Fig. 4). The lateral margin of the SMV-PV is exposed and mobilized using robotic scissors in a caudad to cephalad direction, and venous tributaries are individually ligated with 3-0 silk suture. Very small side branches may be addressed using a 5-mm clip applier, but caution should be used when applying these as they may become dislodged during later manipulation. The superior pancreaticoduodenal vein (vein of Belcher) is divided between silk ties or with a vascular stapler depending on its caliber. Next (Fig. 5), using the robotic Maryland dissector, the adventitia of the SMA is identified just above where the first jejunal branch crosses. Several small but sensitive branches from the genu of the first jejuna branch of the SMV often need to be ligated to expose the SMA. The authors have found 4-0 Prolene suture ligature with ports R2 and R1 to be the safest and most efficient method to address these branches. The SMA lymph nodes usually found posterior but now retracted lateral to the SMA are divided using LigaSure with the SMA in view. Tiny arterial branches are divided with the LigaSure device, whereas clips and LigaSure and 4-0 Prolene suture ligatures are used together on larger vessels, keeping the plane of Leriche in view. The inferior and superior pancreaticoduodenal vessels are divided between 2-0 silk ligatures, with 5-mm clips and LigaSure being used for smaller perforators and the duodenal mesentery. The exposure allows 4-0 or 5-0 Prolene to be used to control bleeding or suture ligation of larger tributaries through ports R2 and R3. The assistant is able to retract and maintain suction in the surgical field though A1 and A2.

Step 7

Robotic gastrointestinal reconstruction is performed in a fashion identical to the open technique, with the sole exception being the substitution of multifilament absorbable 5-0 suture for monofilament. A 2-layer, end-to-side, duct-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunostomy is performed using the modified Blumgart technique. Interrupted pancreatic duct sutures are placed first to facilitate visualization of the ductal mucosa (5-0 Vicryl) using alternating dyed and undyed sutures, which are clipped and reflected out of the way (Fig. 6). Next, transpancreatic, 2-0 silk horizontal mattress sutures are passed to anchor the seromuscular layer of the jejunum to the pancreatic parenchyma. A small enterotomy is made using robotic cautery shears, and an interrupted duct-to-mucosa anastomosis is completed. When necessary, a pancreatic duct stent (5–7F, 7-cm Zimmon pancreatic stent; Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA) is placed to assure duct patency. Secretin (intravenously) is administered to stimulate pancreatic secretion in cases of tiny ducts not being visible despite repeated inspection. The anastomosis is completed with an anterior layer of 2-0 silk sutures. Approximately 10 cm downstream from the pancreaticojejunostomy, a singer-layer end-to-side hepaticojejunostomy is created with 5-0 Vicryl. The suture is placed in a running fashion for duct diameters greater than 5 mm in diameter when visualization is optimal, or in interrupted fashion otherwise. Finally, an antecolic hand-sewn duodenojejunostomy is performed with a posterior layer of interrupted 2-0 silk followed by running 3-0 Vicryl after the duodenum and jejunum are opened. A Connell technique is used anteriorly. An anterior layer of seromuscular sutures is placed.

Pittsburgh experience with robotic-assisted major pancreatic resection

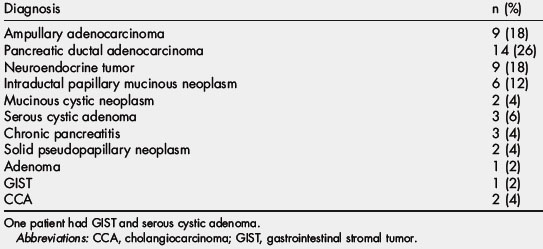

In addition to 40 distal pancreatectomies, 51 patients have undergone robotic-assisted major pancreatectomy at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center since October 2008. Procedures included 42 robotic-assisted pancreaticoduodenectomies (RAPD), 5 central pancreatectomies (RACP), 2 total pancreatectomies (RATP), and 2 duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resections (Frey procedure) with lateral pancreaticojejunostomy (RAFP). The leading indication for surgery was suspected malignancy in 35 patients (66%), premalignant lesions in 9 (17%), and 6 (11%) with benign cysts or calcific chronic pancreatitis. Final pathologic diagnoses are shown in Table 1. Median age of the patients was 70 (range 27–85) years, and 62% (30) were female. Median operative time for the completed procedures was 560 minutes (range 327–848 minutes), including the time to drape and dock the robot (approximated to be 30–45 minutes per case) but excluding general room setup time. Median blood loss was 300 mL (range 50–2000 mL). Twelve patients (20%) required perioperative blood transfusion within 72 hours of surgery. Median hospital length of stay was 10 days (range 4–87 days), with one postoperative death on day 87 (Table 2).

| Diagnosis | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Ampullary adenocarcinoma | 9 (18) |

| Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | 14 (26) |

| Neuroendocrine tumor | 9 (18) |

| Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm | 6 (12) |

| Mucinous cystic neoplasm | 2 (4) |

| Serous cystic adenoma | 3 (6) |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 3 (4) |

| Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm | 2 (4) |

| Adenoma | 1 (2) |

| GIST | 1 (2) |

| CCA | 2 (4) |

One patient had GIST and serous cystic adenoma.

Abbreviations: CCA, cholangiocarcinoma; GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumor.

Table 2 Patient demographics and operative data for major robotic pancreatic resections

| Characteristic | Value (range) |

|---|---|

| No. of patients | 51 |

| Median age in years (range) | 70 (27–85) |

| Female gender, n (%) | 32 (62%) |

| ASA scorea II, III, n (%) | 21 ASA II, 30 ASA III |

| Median body mass index (range) | 26.4 (19.2–39) |

| Median operative time, min (range) | 560 (327–848) |

| Median estimated blood loss, mL (range) | 300 (50–2000) |

| Patients transfused, n (%) | 12 (22%) |

| Median length of stay, days (range) | 10 (4–87) |

a American Society of Anesthesiologists performance score.

To stratify anastomotic risk, pancreatic remnants were classified by International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) criteria [16] including: duct diameter (Types I–III), consistency of the gland (A = soft/normal, B = firm/hard/fibrotic), and length of pancreatic remnant mobilized (pancreatic mobilization 1–3 cm) prior to anastomosis (Table 3). The higher than expected ratio of soft glands and normal ducts size reflects the selection bias toward less invasive lesions in this early series. With the exception of the Frey procedures, all pancreatic duct reconstructions employed an end-to-side, duct-to-mucosa technique. The pancreatic remnant was mobilized 1 to 2 cm (PM2) in all cases to facilitate reconstruction. The majority of the RAPD and RACD reconstructions were Type I anastomoses (pancreaticojejunostomy) with 2 Type II (pancreaticogastrostomy). All patients but one received an internal pancreatic stent to assure patency of the reconstruction: 5F Zimmon stents for Type I ducts (<3 mm) and 7F Zimmon stents for Type II (3–8 mm), and the majority of Type III (>8 mm) ducts.

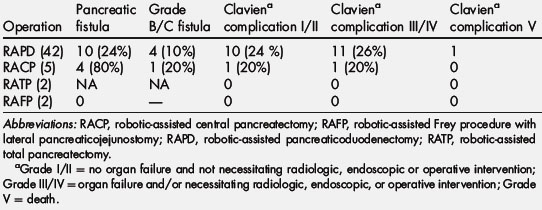

Postoperative fistula outcomes are presented in Table 4. The overall pancreatic fistula rate was 24% (12/49) as defined by strict International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) criteria [17]: 10 out of 42 (21%) in the RAPD group; and 4 out of 5 (80%) in the RACP group. Among the 10 RAPD patients developing pancreatic fistulae, 6 were subclinical (Grade A) and 4 were clinically significant (2 Grade B and 2 Grade C). Of the 3 pancreatic fistulae following RACP, 4 were subclinical (Grade A) and one was clinically significant (Grade C). None of the patients undergoing an RAFP procedure developed a postoperative fistula or complication. Postoperative complications occurring within the first 90 days are presented in Table 4. Clavien Grade III and IV complications occurred in 13 patients (25% of the total study group). Three patients required reoperation due to: postoperative bleeding from the divided stomach [1]; hemorrhage from the GDA stump secondary to a pancreatic leak [1]; and distal bowel obstruction due to an unrecognized Meckel diverticulum leading to biliary anastomotic leak [1]. This patient expired on day 87, due to multisystem organ failure, and is the only mortality in the series (2%). The other 5 complications included sepsis secondary to pancreatic leak (n = 1), bleeding from a GDA pseudoaneurysm in the setting of a pancreatic leak (n = 1), small bowel obstruction and severe delayed gastric emptying presenting 3 weeks after discharge (n = 1), biloma requiring subsequent percutaneous drainage (n = 1), and abdominal abscess requiring interventional radiology drainage (n = 1). Grade I and II complications occurred in 8 patients (27%) and were limited to the RAPD group. These complications included delayed gastric emptying (n = 4), deep venous thromboembolism/pulmonary embolism (n = 2), and wound infection in the right lower quadrant utility incision (n = 2).

The authors evaluated surgical outcomes in their first 20 RAPD procedures and compared them with the second 22 procedures (Table 5). Improvement in perioperative blood loss, risk of pancreatic fistula, and duration of hospital stay was observed between these 2 cohorts. Of interest, the authors observed no reduction in operative times. This finding suggests that the technically demanding portions of the procedure that contribute to morbidity can be mastered in relatively few cases, and raises the possibility that with more experience, outcomes of robotic-assisted pancreatic resection may be better than those following the open approach. The relatively stable operative times likely reflect technological limitations inherent in the current robotic platform (described below).

Table 5 Outcomes in robotic-assisted pancreaticoduodenectomy

| Parameters | First 20 | Second 22 |

|---|---|---|

| Conversion | 7 | 1 |

| Operative time (min) | 593 | 536 |

| Median blood loss (mL) | 595 | 300 |

| Pancreatic fistula | 5 | 2 |

| LOS (days) | 12.3 | 9 |

Abbreviation: LOS, length of hospital stay.

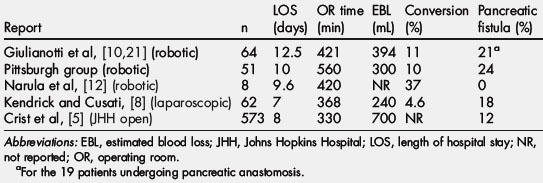

Comparison of outcomes following robotic-assisted major pancreatic resections with selected laparoscopic and open series

The first case report of robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy was made by Giullianoti and colleagues [21] in 2003 as part of a larger series of robotic-assisted general surgery procedures. However, no details regarding the outcomes and approach were included in this initial report. Since that time these investigators have updated that series and reported on the results of 64 major pancreatic resections performed at two different centers (Ospedal Misericordia, Pisa, Italy and University of Illinois, Chicago, IL, USA) [10]. In this series there were 60 RAPD, 3 RACP, and 1 RATP. A majority of the resections were performed for cancer (80%). Among RAPD patients, 19 underwent reconstruction of the pancreatic duct, whereas the remainder had sclerosis of the remnant pancreatic duct. Median operating room time was 421 minutes (range 240–661 minutes) and median blood loss was 394 mL (range 8–1500 mL). The conversion rate was 11%, and 4 patients required reoperations. The overall fistula rate was 31%. For those patients undergoing surgical reconstruction the fistula rate was 4 of 19, or 21%. Other series of RAPD include one by Narula and colleagues [12], who reported the outcomes of 8 cases. Seven of the 8 patients had benign disease, with one cancer. Three (38%) required conversion to open resection. Median operative time was 420 minutes (range 360–500 minutes). There were no reported fistulae or postoperative complications in this small series.

These two early series and the authors’ own from the University of Pittsburgh demonstrate that robotic-assisted major robotic resections can be performed with comparable outcomes to open pancreaticoduodenectomy (see Table 5). Like most minimally invasive procedures, the blood loss for minimally invasive pancreaticoduodenectomies appears to be less than open resection, whereas pancreatic fistula rates are slightly higher. The differences in the pancreatic fistula rate between the minimally invasive and open series may be subject to several biases: (1) stringent ISGPF criteria for grading the pancreatic remnant have only recently been published and widely adopted, accounting for a higher number of asymptomatic fistulae in the more recent minimally invasive series; (2) the minimally invasive series report a higher rate of soft or normal pancreatic remnants, demonstrating selection bias in favor of less technically challenging resections but correspondingly more difficult reconstructions at higher risk of leak; (3) results of small series of minimally invasive major pancreatic resections may represent the learning curve as described for the Pittsburgh experience. Although longer than for open resection, operating times for RAPD are consistent with results at Johns Hopkins in the 1980s and 1990s. It is not unreasonable to assume that with increased familiarly and improved technology with the robotic approach, operating room times may approach those of current open series (Table 6).