Lung Cancer

Clinical Aspects

The goal of this chapter is to extend the discussion of lung cancer into the clinical realm and relate how the pathologic processes considered in Chapter 20 are encountered in a clinical setting. An outline of the major clinical features of lung cancer is followed by a discussion of the diagnostic approach and general principles of management. The chapter concludes with a brief discussion of bronchial carcinoid tumors, malignant mesothelioma, and the clinical problem of the solitary pulmonary nodule.

Clinical Features

Symptoms Relating to Nodal and Distant Metastasis

Distant metastases, most commonly to the brain, bone or bone marrow, liver, and adrenal gland(s), frequently are asymptomatic. In other cases, symptoms depend on the particular organ system involved. Small cell carcinoma is the cell type most likely to generate distant metastases (see Chapter 20). Squamous cell carcinoma is least likely, and both adenocarcinoma and large cell carcinoma occupy an intermediate position.

Paraneoplastic Syndromes

Other paraneoplastic syndromes cannot be attributed to a known hormone, and our understanding of their mechanisms varies. Examples range from a wide variety of neurologic syndromes (some of which appear to be due to autoimmune antibody production) to the soft tissue and bony manifestations of clubbing and hypertrophic osteoarthropathy (see Chapter 3). The nonspecific systemic effects of malignancy, such as anorexia, weight loss, and fatigue, are potential consequences of lung cancer, and it has been hypothesized that production of various mediators, such as tumor necrosis factor, may mediate these systemic effects.

Diagnostic Approach

Macroscopic Evaluation

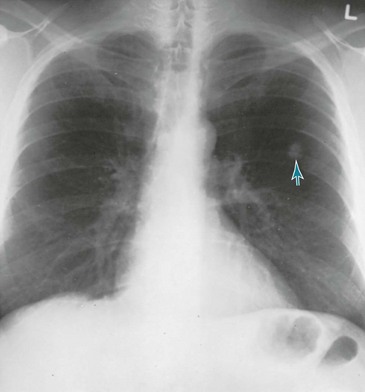

The initial test for detection and macroscopic evaluation of bronchogenic carcinoma is generally the chest radiograph. The presence of a nodule or mass within the lung on chest radiograph always raises the question of lung cancer, especially when the patient has a history of heavy smoking. The location of the lesion may give an indirect clue about its histology: peripheral lesions are more likely to be adenocarcinoma or large cell carcinoma, whereas central lesions are statistically more likely to be squamous cell carcinoma or small cell carcinoma (Figs. 21-1 and 21-2). The chest radiograph is also useful for determining the presence of additional suspicious lesions, such as a second primary tumor or metastatic spread from the original carcinoma. Involvement of hilar or mediastinal nodes or the pleura (with resulting pleural effusion) may be detected on the chest radiograph, and such a finding will substantially affect the overall approach to therapy.

Figure 21-2 Chest radiograph shows adenocarcinoma of lung manifesting as solitary pulmonary nodule (arrow).

A newer technique that has gained increasing popularity in the evaluation of patients with known or suspected lung cancer is positron emission tomography (PET; see Chapter 3). Because of their high metabolic activity, malignant lesions typically exhibit high uptake of the radiolabeled glucose analog 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG). Focal uptake in the region of a parenchymal nodule or mass suggests the lesion is malignant, and uptake in the mediastinum or at distant sites often reflects spread of the tumor to those sites. However, other metabolically active lesions (e.g., focal areas of infection) may also show FDG uptake, so a positive PET scan in the appropriate clinical scenario is very suggestive but is not diagnostic of malignancy.

The best way to directly examine the airways of a patient with presumed or known bronchogenic carcinoma is by bronchoscopy with either a rigid or, much more frequently, a flexible bronchoscope (see Chapter 3). The location and intrabronchial extent of many tumors can be directly observed, and samples can be obtained from the lesion, either for cytologic or histopathologic examination. In addition, the bronchoscopist can assess whether an intrabronchial carcinoma is impinging significantly on the bronchial lumen and causing either partial or complete airway occlusion. Diagnostic specimens can be obtained in many cases even when the lesion is beyond direct visualization with the bronchoscope. In recent years, significant technologic advances in bronchoscopy, such as endobronchial ultrasound and electromagnetic navigation techniques, have increased the diagnostic yield of the procedure for lesions that are difficult to sample by direct visual or fluoroscopic guidance alone.

Microscopic Evaluation

Evaluating lung cancer on a microscopic level is crucial for establishing the specific cell type of the tumor. Some techniques used were mentioned briefly in Chapter 3. Specimens are obtained either for cytologic examination of abnormal cells shed from the tumor or for histopathologic examination of a biopsy specimen obtained directly from the lesion. Cytologic examination can be performed on sputum, washings or brushings obtained through a bronchoscope, or material aspirated from the tumor with a small-gauge needle. Biopsy material can be obtained by passing a biopsy forceps through a bronchoscope, using a cutting needle passed through the chest wall directly into the tumor, or directly sampling tissue at the time of a surgical procedure. Staining techniques for processing these materials are discussed in Chapter 3.

Principles of Therapy

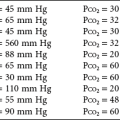

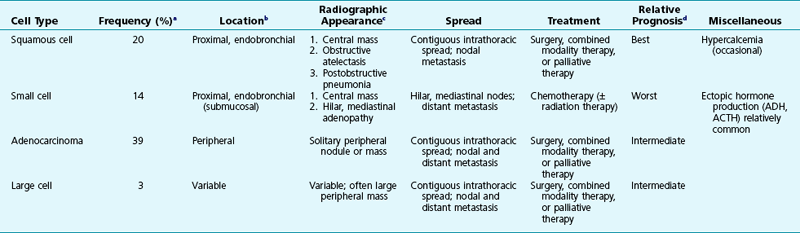

Table 21-1 summarizes many of the specific features of lung cancer discussed in both this chapter and Chapter 20. Each of the major cell types is considered separately, with emphasis on clinical, radiographic, and therapeutic aspects of each category of tumor.

Table 21-1

LUNG CANCER: COMPARATIVE FEATURES

ACTH = Adrenocorticotropic hormone; ADH = antidiuretic hormone.

aApproximate percent of all lung cancers.

bMost common location; for all cell types, variable locations are seen.

cCommon presentations on chest radiograph.

dFor all cell types, the overall prognosis is generally poor.

Malignant Mesothelioma

The primary risk factor for development of malignant mesothelioma is a history of exposure to asbestos, generally in the range of 30 to 40 years earlier. Individuals who have worked in jobs that exposed them to asbestos (see Chapter 20) are at highest risk, but heavy exposure is not necessary for predisposing a person to malignant mesothelioma. In fact, mesothelioma develops even in spouses of asbestos workers, presumably because of inhalation of asbestos dust while exposed to their partners’ clothes.

In patients with malignant mesothelioma, the main symptoms are chest pain, dyspnea, and possibly cough. A number of paraneoplastic syndromes may occur, including disseminated intravascular coagulation, migratory thrombophlebitis, hemolytic anemia, hypoglycemia, and hypercalcemia. The chest radiograph is usually most notable for the presence of pleural fluid and often irregular or lobulated thickening of the pleura (Fig. 21-3). Only a minority of patients have evidence of asbestosis, the interstitial lung disease associated with asbestos exposure. Diagnosis requires biopsy of the pleura and histologic demonstration of the malignancy. Because the tumor originates in the pleura and does not directly communicate with airways, malignant cells are not shed into the tracheobronchial tree and cannot be found on cytologic examination of sputum or bronchoscopy specimens.

Solitary Pulmonary Nodule

Diagnostic possibilities for the solitary pulmonary nodule are listed in Table 21-2. Besides primary lung cancer, the major alternative diagnoses are benign pulmonary neoplasms, solitary metastases to the lung from a distant primary carcinoma, and infections (especially healed granulomatous lesions from tuberculosis or fungal disease). Estimating the likelihood of a malignant versus a benign lesion from its radiographic appearance is based on three major factors:

Table 21-2

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF THE SOLITARY PULMONARY NODULE

NEOPLASMS

VASCULAR ABNORMALITY

INFECTION

MISCELLANEOUS

1. Growth. Perhaps the most helpful piece of information a physician can have is a prior chest radiograph. Comparison of old and new films shows whether a lesion is stable and gives an approximation of the rate of growth. Although it is difficult to say with certainty whether a lesion is benign or malignant based on the rate of growth, absence of any increase in size for at least 2 years is an extremely good (but not infallible) indication a lesion is benign.

2. Calcification. The presence of calcification within a pulmonary nodule, best demonstrated on CT scan, may favor the diagnosis of a benign lesion, especially a granuloma or hamartoma. If certain patterns of calcification are found—diffuse speckling, dense calcification, laminated (onion-skin) calcification, or “popcorn” calcification—the lesion almost assuredly is benign. On the other hand, calcification at the periphery of a lesion or amorphous calcification within the lesion may be suggestive of malignancy. For example, a peripheral area of calcification is entirely consistent with a scar carcinoma arising in the region of an old calcified parenchymal scar (e.g., old calcified granuloma).

3. Border appearance. An irregular or spiculated margin is suggestive of a malignant lesion, whereas a benign lesion commonly has a smooth and discrete border.

The practical question of how to evaluate and manage these cases often is difficult, and the decision-making process must be individualized for each patient. A simple noninvasive test such as sputum cytologic examination is most helpful if results are positive, but the yield is low, even with peripheral nodules that are eventually proven to be carcinoma. Unless the lesion has been stable on chest radiograph for more than 2 years, chest CT scanning is performed routinely to look at border characteristics, assess the presence and pattern of calcification, and identify other abnormalities, especially lymph nodes within the mediastinum. An algorithm has been developed by the Fleischner Society to guide appropriate radiographic follow-up for a given patient, depending upon the size of the lesion and the patient’s risk factors for lung cancer. PET scanning (see Chapter 3), when available, is being performed increasingly when the diagnosis is uncertain after evaluation of the clinical information and other imaging studies. Uptake of labeled FDG suggests the lesion has high metabolic activity and could be malignant, whereas lack of uptake suggests a metabolically inactive benign lesion. Unfortunately, slower-growing malignant neoplasms may have PET characteristics that are similar to benign lesions.

Lung Cancer: General Reviews and Clinical Aspects

American College of Chest Physicians. Diagnosis and management of lung cancer: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, 2nd ed. Chest. 2007;132(Suppl):1S–422S.

Ettinger, DS, Akerley, W, Bepler, G, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8:740–801.

Ganti, AK, Huang, CH, Klein, MA, et al. Lung cancer management in 2010. Oncology (Williston Park). 2011;25:64–73.

Ginsberg, MS, Grewal, RK, Heelan, RT. Lung cancer. Radiol Clin North Am. 2007;45:21–43.

Matthay, RM. Lung cancer. editor. Clin Chest Med. 2002;23:1–277.

Rodriguez, E, Lilenbaum, RC. Small cell lung cancer: past, present, and future. Curr Oncol Rep. 2010;12:327–334.

Spiro, SG, Silvestri, GA. One hundred years of lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:523–529.

Zalcman, G, Bergot, E, Lechapt, E. Update on nonsmall cell lung cancer. Eur Respir Rev. 2010;19:173–185.

Lung Cancer: Diagnostic Approaches

Alberts, WM. Diagnosis and management of lung cancer executive summary: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, 2nd ed. Chest. 2007;132:1S–19S.

Birim, O, Kappetein, AP, Stijnen, T, et al. Meta-analysis of positron emission tomographic and computed tomographic imaging in detecting mediastinal lymph node metastases in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:375–382.

Croswell, JM, Baker, SG, Marcus, PM, et al. Cumulative incidence of false-positive test results in lung cancer screening: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:505–512.

Detterbeck, FC, Boffa, DJ, Tanoue, LT. The new lung cancer staging system. Chest. 2009;136:260–271.

Fischer, B, Lassen, U, Mortensen, J, et al. Preoperative staging of lung cancer with combined PET-CT. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:32–39.

Hollings, N, Shaw, P. Diagnostic imaging of lung cancer. Eur Respir J. 2002;19:722–742.

Lababede, O, Meziane, M, Rice, T. Seventh edition of the cancer staging manual and stage grouping of lung cancer: quick reference chart and diagrams. Chest. 2011;139:183–189.

Maziak, DE, Darling, GE, Inculet, RI, et al. Positron emission tomography in staging early lung cancer: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:221–228.

National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:395–409.

Schmidlin, EJ, Sundaram, B, Kazerooni, EA. Computed tomography screening for lung cancer. Radiol Clin North Am. 2012;50:877–894.

Silvestri, GA, Gould, MK, Margolis, ML, et al. Noninvasive staging of small cell lung cancer: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, ed 2. Chest. 2007;132:178S–201S.

Wender, R, Fontham, ET, Barrera, E, Jr., et al. American Cancer Society lung cancer screening guidelines. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013. Jan 11

Cataldo, VD, Gibbons, DL, Pérez-Soler, R, et al. Treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer with erlotinib or gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:947–955.

Demedts, IK, Vermaelen, KY, van Meerbeeck, JP. Treatment of extensive-stage small cell lung carcinoma: current status and future prospects. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:202–215.

Ernst, A, Feller-Kopman, D, Becker, HD, et al. Central airway obstruction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:1278–1297.

Maemondo, M, Inoue, A, Kobayashi, K, et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2380–2388.

Mazzone, PJ, Arroliga, AC. Lung cancer: preoperative pulmonary evaluation of the lung resection candidate. Am J Med. 2005;118:578–583.

Sculier, JP, Moro-Sibilot, D. First- and second-line therapy for advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:915–930.

Spira, A, Ettinger, DS. Multidisciplinary management of lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:379–392.

Temel, JS, Greer, JA, Muzikansky, A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742.

Visbal, AL, Leighl, NB, Feld, R, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2005;128:2933–2943.

Bertino, EM, Confer, PD, Colonna, JE, et al. Pulmonary neuroendocrine/carcinoid tumors: a review article. Cancer. 2009;115:4434–4441.

Brokx, HA, Risse, EK, Paul, MA, et al. Initial bronchoscopic treatment for patients with intraluminal bronchial carcinoids. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133:973–978.

Fink, G, Krelbaum, T, Yellin, A, et al. Pulmonary carcinoid: presentation, diagnosis, and outcome in 142 cases in Israel and review of 640 cases from the literature. Chest. 2001;119:1647–1651.

Kulke, MH, Mayer, RJ. Carcinoid tumors. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:858–868.

Machuca, TN, Cardoso, PF, Camargo, SM, et al. Surgical treatment of bronchial carcinoid tumors: a single-center experience. Lung Cancer. 2010;70:158–162.

Bagheri, R, Haghi, SZ, Rahim, MB, et al. Malignant pleural mesothelioma: clinicopathologic and survival characteristic in a consecutive series of 40 patients. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;17:130–136.

British Thoracic Society. BTS statement on malignant mesothelioma in the UK, 2007. Thorax. 2007;62(Suppl II):ii1–ii19.

Campbell, NP, Kindler, HL. Update on malignant pleural mesothelioma. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;32:102–110.

Fuhrer, G, Lazarus, AA. Mesothelioma. Dis Mon. 2011;57:40–54.

Robinson, BW, Lake, RA. Advances in malignant mesothelioma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1591–1603.

Robinson, BW, Musk, AW, Lake, RA. Malignant mesothelioma. Lancet. 2005;366:397–408.

Scherpereel, A, Astoul, P, Baas, P, et al. Guidelines of the European Respiratory Society and the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons for the management of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:479–495.

Jeong, YJ, Yi, CA, Lee, KS. Solitary pulmonary nodules: detection, characterization, and guidance for further diagnostic workup and treatment. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:57–68.

MacMahon, H, Austin, JH, Gamsu, G, et al. Guidelines for management of small pulmonary nodules detected on CT scans: a statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 2005;237:395–400.

Ost, D, Fein, AM, Feinsilver, SH. Clinical practice. The solitary pulmonary nodule. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2535–2542.

Ost, DE, Gould, MK. Decision making in patients with pulmonary nodules. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:363–372.

van Klaveren, RJ, Oudkerk, M, Prokop, M, et al. Management of lung nodules detected by volume CT scanning. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2221–2229.

Winer-Muram, HT. The solitary pulmonary nodule. Radiology. 2006;239:34–49.