17.2 Ischaemia and infarction167

17.3 Immunological disorders167

17.4 Neoplasia168

17.1. Inflammation and infection

Infectious enterocolitis

Infectious diseases of the bowel most commonly present with diarrhoea, which is an increase in stool mass, stool frequency or stool fluidity. Diarrhoea can result from a number of mechanisms (see Table 28). The pathogen responsible – which may be bacterial, viral, parasitic, protozoal or fungal – varies with patient age, nutrition, immune status and environment, and is identifiable in only approximately half of all cases.

| Type of diarrhoea | Mechanism | Major causes |

|---|---|---|

| Secretory diarrhoea | Stimulation of gut secretion | Viral infection |

| Bacterial infection | ||

| Neoplasms producing secretagogues | ||

| Osmotic diarrhoea | Excessive osmotic forces exerted by increased concentration of luminal solutes | Laxative therapy |

| Malabsorption (many causes) | ||

| Lactase deficiency | ||

| Exudative diarrhoea | Stools containing blood and inflammatory debris secondary to tissue damage | Crohn’s disease |

| Ulcerative colitis | ||

| Bacterial infections | ||

| Protozoal infections | ||

| Abnormal gut motility | Various causes of altered gut transit time and motility | Irritable bowel syndrome |

| Diabetic neuropathy | ||

| Post-bowel surgery |

Viruses

Rotavirus affects primarily children aged 6months to 2years, and is responsible for an estimated 140 million cases of infective enterocolitis and 1 million deaths per year. Viral infection damages mature surface epithelial cells in the small intestine mucosa, which are replaced by immature secretory cells. This results in a loss of absorptive ability and increased gut secretions, producing a mixed osmotic and secretory diarrhoea (see Table 28). In older children and young adults, the majority of non-bacterial gastroenteritis is due to Norwalk-like viruses. Viral infection typically provokes cellular immunity involving cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Biopsies of intestinal mucosa are rarely undertaken in suspected viral infection, as symptoms of vomiting and diarrhoea are often self-limiting and of short duration. However, in an immunocompetent individual, the microscopic appearance of established viral infection would characteristically include epithelial cell damage and lymphocytic infiltration of the mucosa indicative of host immune response.

Bacteria

Bacteria cause disease in the gut by a number of mechanisms:

• effects of preformed bacterial toxins present in contaminated food

• toxin production by organisms within the gut

• enteroinvasive infection, in which organisms proliferate, invade and destroy the intestinal mucosal epithelium.

Enterotoxins Enterotoxins are polypeptides which cause diarrhoea. Some, such as cholera toxin, cause massive secretion of fluid in the absence of tissue damage (secretory and osmotic diarrhoea). Cholera toxin exerts its effects by persistently activating the cytoplasmic enzyme adenylate cyclase, causing profound secretion of chloride, sodium and water.

Secretory toxins Secretory toxins produced by Escherichia coli are the major cause of traveller’s diarrhoea.

Cytotoxins Cytotoxins produced, for example, by Shigella and cytotoxic strains of E. coli, cause tissue damage with epithelial cell necrosis and an acute inflammatory reaction. Cytotoxins usually induce ‘dysentery’ – low volume, painful, bloody diarrhoea.

Although bacterial infection is frequently confined to the gut, systemic disease may occasionally occur. Organisms may enter the bloodstream (causing a bacteraemia), multiply (septicaemia) and spread to other organs (dissemination). Inflammatory mediators activated by bacterial toxins or by products of damaged host cells may result in fever, lowered blood pressure and ultimately septic shock (see Ch. 5), which is often fatal. Typhoid fever is the name given to the generalised illness caused by infection by Salmonella typhimurium, which can include chronic inflammation of the biliary tree, joints, bones and meninges in addition to intestinal involvement.

Pseudomembranous colitis

Pseudomembranous colitis is an acute infectious disease of the colorectum, which is a common cause of diarrhoea in hospitalised patients receiving broad spectrum antibiotic therapy. The organism responsible (Clostridium difficile) is a normal toxin-producing commensal of the gut. Antibiotic therapy appears to alter the balance of the gut flora, allowing C. difficile to flourish. The toxin damages the colonic mucosa, causing an acute inflammatory reaction with the formation of a typical ‘pseudomembrane’. The pseudomembrane is visible endoscopically as an irregular dark yellow coating over the bowel surface; microscopically it contains mucus and acute inflammatory debris including fibrin and degenerate neutrophils. The toxin of C. difficile can be identified in the stool of symptomatic patients.

Acute appendicitis

Acute inflammation of the appendix is the most common acute abdominal condition requiring surgery. It can occur at any age, although it is relatively rare in the very young and very old. Most cases are thought to arise secondary to obstruction of the appendiceal lumen by faeces. The exact sequence of events is unknown, but may involve a combination of bacterial proliferation and increased intraluminal pressure causing vascular obstruction and ischaemia. The affected appendix shows the hallmarks of acute inflammation – intense neutrophil polymorph infiltration and oedema, with tissue necrosis and peritonitis in advanced cases. The serosal surface of the organ becomes covered with an acute inflammatory exudate composed of fibrin and neutrophils. If surgery is delayed there is a risk of appendiceal rupture, with localised abscess formation or generalised peritonitis with septicaemia. Chronic inflammation is very unusual in the appendix. Small scarred appendices, presumably representing the fibrotic end stage of repeated acute inflammation, are sometimes seen in older adults.

Peritonitis

Generalised acute inflammation of the peritoneum can arise secondary to bacterial invasion or chemical irritation. Bacterial peritonitis may complicate many inflammatory processes, including acute appendicitis, cholecystitis, perforated peptic ulcer, diverticulitis, bowel ischaemia and salpingitis. Infective peritonitis may also follow abdominal trauma or medical intervention (e.g. peritoneal dialysis). Chemical inflammation of the peritoneum may occur when bile, pancreatic enzymes, foreign material or blood (endometriosis, trauma, surgery) are released into the peritoneal cavity. Healing of peritonitis can result in the formation of fibrous adhesions between bowel loops. These adhesions can subsequently cause abdominal pain and bowel obstruction.

Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis

Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are often grouped together under the term chronic idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease. As this term suggests, Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are of unknown aetiology, and it has been suggested that they may represent different parts of the spectrum of a single disease process. However, there are important clinical and pathological differences between these two conditions.

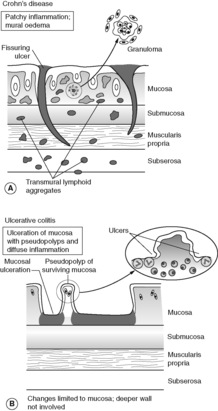

Crohn’s disease

Crohn’s disease is characterised by discontinuous, sharply demarcated areas (‘skip lesions’) of transmural chronic inflammation. Microscopically, aggregates of lymphocytes are seen in all layers of affected bowel wall. Non-necrotising granulomas, composed of epithelioid macrophages with multinucleated giant cells, are seen in approximately 60% of cases. Fissuring ulcers are another characteristic histological feature of Crohn’s disease; these linear ulcers can also be seen with the naked eye, and often impart a ‘cobblestone’ appearance to the bowel mucosa when viewed endoscopically or in a surgical resection specimen. The intestinal wall becomes thickened by oedema in acute stages and flare-ups of Crohn’s disease, and by fibrosis in chronic disease, leading to stricture formation. Extension of fissuring ulceration through to the serosal surface of the bowel can result in perforation, abscess formation, adhesions, fistulas and sinus tracts. A fistula is an abnormal communication between two epithelial surfaces (e.g. a colovesical fistula joins colonic mucosa to bladder mucosa). The fistulous tract itself is lined by epithelium or by granulation tissue. A sinus is a blind-ending tract, which connects with the skin or another epithelial surface at one end.

Crohn’s disease manifests clinically with intermittent diarrhoea, fever and abdominal pain. Symptoms of the initial attack may mimic acute appendicitis. The terminal ileum is the commonest single site of disease and involvement of this region by Crohn’s disease can cause symptoms relating to malabsorption. Crohn’s disease typically waxes and wanes with recurrent attacks over many years, but there are intervening symptom-free periods of remission. Later presentations include bowel obstruction secondary to fibrous stricturing and symptoms related to fistula formation. There is a slight increased risk of colorectal cancer. The features of Crohn’s disease are summarised in Figure 43A.

Ulcerative colitis

Ulcerative colitis is also a chronic relapsing inflammatory condition. It is slightly more common than Crohn’s disease (incidence of ulcerative colitis is 4–6 per 100 000) but shares peak onset in early adulthood, equal frequency in males and females and predilection for white people. Unlike Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis is characterised by continuous disease extending proximally from the rectum, involving a variable distance of colon up to and occasionally including the terminal ileum. Isolated small intestinal disease does not occur in ulcerative colitis. Inflammation is restricted to the colonic mucosa, with occasional involvement of the submucosa. During acute attacks of colitis, there may be extensive mucosal ulceration, from which multiple islands of surviving epithelium stand proud as ‘pseudopolyps’. Microscopically the lamina propria of residual mucosa shows diffuse chronic inflammation with lymphocytes and plasma cells, and acute inflammation of mucosal glandular crypts. Granulomas are characteristically absent. With progressive disease the mucosa becomes atrophic, with disruption of glandular architecture and gland loss. There is a risk of epithelial dysplasia and subsequent carcinoma developing in longstanding ulcerative colitis. This risk is greatest in patients having involvement of the entire large intestine (pancolitis). The features of ulcerative colitis are summarised in Figure 43B.

Ulcerative colitis commonly manifests as recurrent attacks of bloody, mucoid diarrhoea and abdominal pain. Occasionally patients present with severe bleeding and fluid imbalance. Severe acute ulcerative colitis is one of the causes of toxic megacolon (see Box 23). As inflammation is restricted to the mucosa and submucosa, fistulae and strictures do not occur in ulcerative colitis.

Box 23

Definition: Marked dilatation of colon

Causes:

• toxic megacolon – a complication of severe acute inflammation, most commonly seen in ulcerative colitis

• obstruction – neoplasia, inflammatory stricture

• infection – destruction of enteric nerve plexuses in Chagas’ disease

• congenital – Hirschsprung’s disease

Clinical course: High risk of gangrene and perforation in toxic megacolon

Diverticular disease

A diverticulum is essentially a blind pouch, which is lined by epithelium and communicates with the bowel lumen. The wall of a true (congenital) diverticulum contains all layers of the bowel wall (mucosa, submucosa and muscularis propria). Diverticula occur in the small intestine as the solitary Meckel’s diverticulum (a remnant of the embryonic vitelline duct) or as multiple jejunal lesions. However, the distal large intestine is the most common site. Approximately half of all adults over 60 have developed (acquired) multiple, small, flask-like or spherical outpouchings in the sigmoid colon. The diverticula extend from the luminal surface into the deep muscularis mucosa and pericolic fat, and are a frequent incidental finding on barium enema examination in elderly patients. Obstruction of a diverticulum by faeces can cause inflammation (diverticulitis), pericolic abscess formation and local or generalised peritonitis. Chronic inflammation and fibrosis may complicate acute diverticulitis, leading to fistula formation and colonic stricture.

Diverticula formation occurs at points of weakness in the colonic wall where vessels and nerves penetrate the muscle coat. Low-fibre diet is thought to contribute to pathogenesis; low stool bulk results in exaggerated peristalsis and increased intraluminal pressure in the affected colon. Symptomatic diverticular disease may present with cramping or continuous lower abdominal pain, constipation or alternating bowel habit, and chronic blood loss.

17.2. Ischaemia and infarction

Intestinal ischaemia can be acute or chronic, and result from both arterial and venous disease. Elderly adults are most frequently affected. Atherosclerosis is often the underlying pathology. Mesenteric arteries supplying the gut may be blocked by thrombosis superimposed on atherosclerosis, or by embolisation of fragments of atheromatous plaque originating from the aorta. Non-occlusive bowel ischaemia can follow hypoperfusion due to, for example, cardiac failure, shock or dehydration. The ‘watershed areas’ of the colon – splenic flexure and rectum – which lie between the major arterial blood supplies are especially vulnerable. Mesenteric venous thrombosis can complicate sepsis, neoplasia, liver cirrhosis and abdominal surgery. Therapeutic radiotherapy used in the treatment of malignant disease can cause vascular damage with progressive narrowing and occlusion of arteries. Radiation enterocolitis most commonly occurs in the small intestine of patients receiving treatment for carcinoma of the cervix.

Ischaemic injury may be restricted to the mucosa and submucosa of the gut or may involve all layers of the bowel wall. In full-thickness acute bowel infarction, the serosal surface of the gut appears plum coloured due to congestion and reflow of blood into the damaged tissue. The intestinal lumen usually contains blood or blood-stained mucus. Histological changes of infarction (ischaemic necrosis) and oedema are present. Acute small bowel infarction has a high mortality, due to the short time interval between onset of symptoms and development of bowel perforation or septicaemia. The poor prognosis is partly due to coexistent cardiac and vascular disease in the at-risk elderly population. Less severe vascular occlusion which develops gradually can present as chronic ischaemic colitis, with patchy mucosal ulceration. Chronic ischaemia involving the submucosa may heal by fibrosis, causing colonic stricture.

17.3. Immunological disorders

Coeliac disease

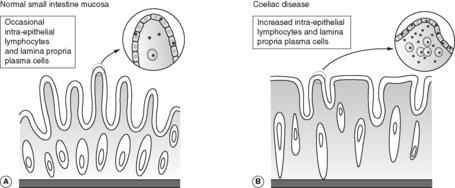

Coeliac disease is a chronic inflammatory condition of the small intestinal mucosa, in which immunologically mediated injury to the epithelium causes malabsorption. It is also known as coeliac sprue and gluten-sensitive enteropathy. The disease is relatively common in white people of European origin (prevalence of 1 : 2000–3000). There is evidence of a genetic predisposition to coeliac disease, with family clustering and high frequency of association with certain human leucocyte antigen (HLA) alleles. Affected individuals develop an immune response to gluten, which contains the protein component gliadin in wheat and closely related grains (oat, barley and rye). Gliadin sensitive B cells accumulate in the small intestinal mucosa on exposure to gluten, and antigliadin antibodies are present in the blood. Characteristically, the small bowel mucosa loses its normal villous architecture and becomes flat. Microscopically there is diffuse chronic inflammation with greatly increased numbers of lymphocytes accumulating within the surface epithelium (Figure 44). The lamina propria contains many plasma cells. These histological abnormalities revert to normal when gluten is excluded from the diet, with subsequent improvement in clinical symptoms. There is a small long-term risk of malignancy (small intestinal lymphoma).

|

| Figure 44 |

Graft-versus-host disease

Patients treated with donated bone marrow receive an allograft of foreign lymphocytes, which are able to mount an immune response against their new host. Graft-versus-host disease has acute and chronic phases. The acute phase may involve the intestinal mucosa, producing severe watery diarrhoea, intestinal haemorrhage and sepsis.

17.4. Neoplasia

The majority of tumours occurring in the lower gastrointestinal tract arise from the glandular epithelium of the large bowel mucosa. Colorectal adenocarcinoma is the second commonest cause of cancer mortality (after lung cancer) in the UK. The jejunum and ileum together make up 75% of the entire intestinal length but are responsible for only 5% of intestinal tumours.

Polyps

Polyps are tissue masses, which protrude into the bowel lumen. They may be described as pedunculated (when there is a recognisable stalk) or sessile (when the polyp has a broad flat base). The word ‘polyp’ is not synonymous with neoplasia, as polyps may be inflammatory, hyperplastic or hamartomatous in nature, as well as neoplastic (see Box 24). Benign tumours of colonic epithelium are often polypoid in structure. Occasionally, masses arising from deeper in the bowel wall (for example, smooth muscle tumours developing in the muscularis propria) may project into the bowel lumen in a polypoid fashion.

Box 24

Metaplastic (hyperplastic) polyps

• Commonest polyps

• Arise from ?hypermaturation of glandular epithelium

• Very low (if any) malignant potential

Hamartomatous polyps*

• Peutz–Jeghers syndrome

• Juvenile polyps

• Cowden syndrome

Inflammatory polyps

• Ulcerative colitis

• Crohn’s disease

• Diverticular disease

• Chronic infections

Neoplastic polyps

• Adenomas

• Adenocarcinomas

Peutz–Jeghers polyps arising in the jejunum and ileum consist of a branching smooth muscle core covered by small intestinal-type epithelium.

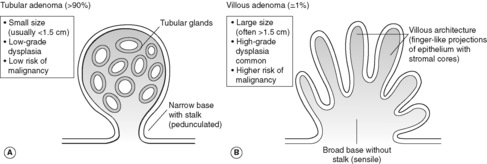

Adenomatous polyps

Adenomatous polyps are benign epithelial neoplasms, and very common in the colon. Up to 50% of all adults over the age of 60 in the UK have at least one. They are classified as tubular (>90%), tubulovillous (5–10%) or villous (1%) according to the mixture of tubular glands and villous (finger-like) projections within the polyp (Figure 45). Adenomas are much more common in the large intestine than in the small intestine, and occur more frequently on the left side (rectum and sigmoid) than the right. Histologically, adenomas show mild, moderate or severe dysplasia. Milder degrees of cellular atypia are usual in small, pedunculated tubular adenomas, but large, sessile villous adenomas frequently show high-grade dysplasia, and up to 40% will contain invasive malignancy on microscopic examination. Most adenomas are asymptomatic and first identified on sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopic examination. Occult or overt bleeding, and rarely mucus hypersecretion per rectum can occur.

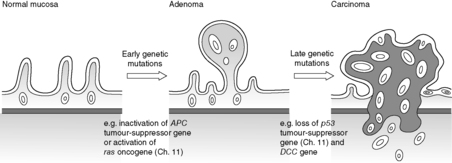

The adenoma-carcinoma sequence

There is good evidence that many colorectal carcinomas evolve from pre-existing benign adenomas, which subsequently become malignant.

• Populations with high prevalence of colorectal adenomas also have a high incidence of large-bowel adenocarcinoma.

• The distribution of adenomas within the colon and rectum mirrors that of adenocarcinomas (left side greater than right side).

• The peak age incidence of adenomas precedes that of adenocarcinomas.

• Foci of invasive adenocarcinoma can be seen within some adenomatous polyps.

• The risk of developing colorectal adenocarcinoma is related to the number of adenomas the patient has developed.

• Removing adenomas decreases the incidence of colorectal adenocarcinoma.

Progression from the normal colonic epithelial cell to adenoma and then to carcinoma requires accumulation of DNA damage in key genes that control cellular growth, differentiation and apoptosis (Figure 46). However, the precise sequence and nature of these multiple genetic ‘hits’ probably varies between individual tumours.

|

| Figure 46 |

Colorectal cancer

Colorectal adenocarcinoma accounts for 98% of all large intestinal malignancies. Although worldwide in distribution, the incidence is much higher in North America, Australia and northern Europe than in Japan, South America and Africa. This geographical distribution suggests that differences in lifestyle have an important aetiological role. The typical Western low fibre, high fat and high refined carbohydrate diet appears associated with higher risk of development of malignancy. Peak incidence of colorectal cancer is between 60 and 70years of age. Rectal lesions are twice as common in men than women, but colonic tumours occur with equal sex incidence. See Table 29.

| Incidence | Usually over 50, unless associated with inherited genetic condition, e.g. FAP, HNPCC |

|---|---|

| Risk factors | Adenomas, FAP, HNPCC; slightly increased risk in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease |

| High fat, low fibre diet | |

| Protective factors | High fibre, low fat diet, ?aspirin |

| Associated lesions | Colorectal adenomas |

| Common clinical presentation | Change in bowel habit, rectal bleeding, iron deficiency anaemia |

| Location | Sigmoid, rectum, caecum (but can occur anywhere in large bowel) |

| Macroscopic appearance | Usually polypoid, often ulcerated |

| Histological features | Adenocarcinoma (gland-forming) |

| Pattern of spread | Lymph nodes, liver (via blood); through peritoneal surface, directly into adjacent bowel loops |

| Lower rectal tumours can directly invade bladder and pelvic organs | |

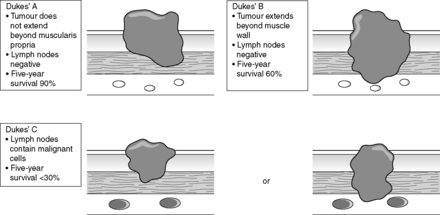

| Prognosis (per cent 5-year survival) | Related to stage; approximately 90% for Dukes’ A, 60% Dukes’ B, 30% Dukes’ C |

As described in the previous section, many colorectal cancers arise from adenomas. Risk of malignant transformation is greatest in large villous adenomas. Although many of these adenomas occur spontaneously, some arise in patients with inherited genetic abnormalities.

Familial adenomatous polyposis (familial polyposis coli)

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP, familial polyposis coli) is a rare autosomal dominant disorder in which patients typically develop 500–2500 adenomas within the large intestine before the age of 30. Unless prophylactic colectomy is performed at an early age, virtually all patients will develop invasive malignancy in at least one of these polyps.

Hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer

Another form of familial colorectal cancer accounts for around 10% of all cases, and is also associated with malignancy outside the gut (including ovarian and endometrial cancer).

People with hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) have inherited mutations of DNA repair genes on chromosome 2. DNA damage can accrue unchecked throughout life and when growth-controlling genes are affected, malignancies may develop. Tumours show a preponderance for the right side of the colon, are often mucin-rich and develop 10–20years before sporadic colorectal cancer. It is important to identify individuals with suspected HNPCC so that they can be regularly examined to exclude extra-intestinal malignancies, and so that family members can be screened for the condition.

Colorectal cancer can not only grow into the bowel lumen as a polypoid mass, but it can also invade into the intestinal wall. Circumferential involvement can cause obstruction, which classically has an ‘apple-core’ appearance on barium enema examination. Ulceration and bleeding are common. In distal colonic and rectal lesions, fresh blood is often passed per rectum. In more proximal tumours, haemorrhage may be occult – the blood becomes altered on passage through the bowel and may not be recognised in the stool. It is not uncommon for caecal cancers to present with unexplained iron deficiency anaemia. Less specific symptoms of colorectal cancer include abdominal pain and alteration of bowel habit.

Microscopically, colorectal cancers show mucin production. They may be well, moderately or poorly differentiated (tumour grade). The extent of spread (stage) is of great importance in prognosis. The Dukes’ staging system is commonly used in the UK (Figure 47).

Carcinoid tumours

The normal intestinal mucosa contains a population of scattered neuroendocrine (NE) cells, which are located in the gland bases (crypts). As their name suggests, these cells show features of both neuronal and endocrine differentiation, and produce a variety of peptide hormones. Tumours arising from NE cells account for approximately 50% of all small intestinal neoplasms, and are often collectively referred to as carcinoid tumours. All are potentially malignant, but behaviour depends on site of origin, depth of invasion and tumour size. Gut carcinoids are most commonly seen in the appendix, and often present as an incidental finding in routine appendicectomies. Some carcinoids secrete functional hormones which produce symptoms. Examples include gastrinomas, which are associated with multiple gastric and duodenal ulcers (Zollinger–Ellison syndrome) and insulinomas, which can present with the effects of hypoglycaemia secondary to tumour production of insulin. The carcinoid syndrome is rare and only occurs in malignant tumours that have metastasised to the liver. Patients experience episodes of facial flushing and diarrhoea, related to hormone production by the tumour (probably excess serotonin).

Lymphoma

Intestinal involvement by malignant lymphoma may occur in widespread node-based disease or as a localised lymphoma arising within the gut itself. Primary bowel lymphomas arise from mucosal associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), and tend to remain localised to the bowel in the early stages. Primary intestinal lymphomas can be associated with immunological disorders including coeliac disease and HIV infection.

Other primary intestinal neoplasms

Mesenchymal neoplasms of the large intestine include benign tumours of fat (lipomas) and gastrointestinal stromal tumours, which may show smooth muscle or neuronal differentiation.

The lower anal canal is lined by squamous epithelium. Most malignancies of the anus resemble the squamous cell carcinomas seen elsewhere in the skin.

17.5. Miscellaneous conditions

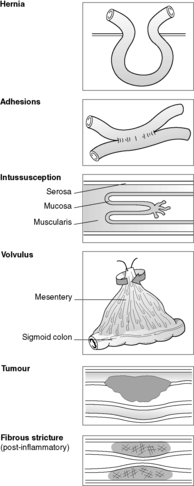

Obstruction

Obstruction of the small and large bowel can occur in a number of pathological processes, some of which (Crohn’s disease, ischaemic colitis, diverticulitis and malignant neoplasms) have already been described. The following four conditions – hernias, adhesions, intussusception and volvulus – account for around 80% of cases of bowel obstruction (Figure 48).

|

| Figure 48 |

Hernia

Hernia is the name given to a pouch-like peritoneal-lined sac that protrudes through a defect or weak area in the peritoneal cavity. Common sites for herniation include the inguinal and femoral canals, the umbilicus and surgical scars. The hernial sac often contains loops of small bowel, and sometimes omentum or large bowel, which can become trapped. Pressure at the neck of the hernia can impair venous return, causing stasis and oedema, and eventual infarction. Permanent trapping of bowel within the hernia is known as incarceration.

Fibrous adhesions

Fibrous adhesions between intestinal loops and other peritoneal structures can follow any cause of peritoneal inflammation, and are particularly common after abdominal or pelvic surgery.

Intussusception

Intussusception occurs when one segment of bowel becomes telescoped into the immediately adjacent (distal) segment. Intussusception can arise within previously normal intestine in children, sometimes in relation to hyperplastic lymphoid tissue. In adults, a mass lesion (usually a neoplasm) is often found at the site of intussusception.

Volvulus

Volvulus is the complete twisting of a bowel loop around its mesenteric attachment. This cause of obstruction is most frequent in the sigmoid colon of older adults.

Large intestinal haemorrhage

As mentioned earlier in this chapter, infectious colitis, diverticulitis, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease and colonic neoplasms may all present with rectal bleeding. Two further clinically important causes of colonic bleeding are haemorrhoids and angiodysplasia.

Haemorrhoids

Haemorrhoids are common abnormalities, consisting of dilated thick-walled veins in the anus and rectal submucosa. These abnormal vessels may protrude from the anal orifice and become traumatised, causing haemorrhage and thrombosis. Predisposing factors for developing haemorrhoids include constipation, pregnancy and portal hypertension (see Ch. 18).

Angiodysplasia

Angiodysplasia is a condition of unknown aetiology, characterised by the presence of dilated blood vessels in the mucosa and submucosa of the large intestine. The caecum is the most common site. Angiodysplasia accounts for up to 20% of cases of symptomatic lower intestinal haemorrhage in the elderly.

Self-assessment: questions

One best answer questions

2. A 7-year-old girl presents with symptoms of acute appendicitis and peritonitis. Her appendix is removed at emergency laparotomy. The most likely microscopic changes on histological examination are:

a. granulomatous inflammation

b. neutrophil polymorph inflammation confined to the mucosa

c. scarring

d. neutrophil polymorph inflammation involving the muscle coat and the serosa

e. obstruction by carcinoid tumour

True-false questions

1. The following are correctly paired:

a. ulcerative colitis – sclerosing cholangitis

b. diverticular disease – increased risk of malignancy

c. pseudomembranous colitis – C. difficile

d. coeliac disease – anti-DNA antibodies

e. Peutz–Jeghers syndrome – hamartomatous polyps

2. Colorectal cancer:

a. always arises from a pre-existing benign tumour (adenoma)

b. may present with iron deficiency anaemia

c. has a 5-year survival of less than 30% in the absence of lymph node involvement

d. occurs with increased incidence in cigarette smokers

e. shows squamous differentiation in 20% of cases

3. The following statements are true:

a. cytotoxin-producing bacteria cause diarrhoea without tissue damage

b. fibrous strictures occur in ischaemic colitis

c. intussusception is a cause of bowel obstruction in infants

d. coeliac disease is characteristically associated with increased numbers of neutrophil polymorphs in the surface epithelium of the small intestine

e. bowel obstruction is a long-term complication of abdominal surgery

4. Concerning small bowel infarction:

a. it only occurs in the presence of arterial occlusion

b. mesenteric artery atherosclerosis is a common predisposing factor

c. peritonitis is a rare complication

d. necrosis confined to the mucosa heals by scarring

e. the mortality rate is low

Case history questions

Case history 1

A 24-year-old woman presents with several weeks’ history of diarrhoea, abdominal pain and weight loss. On questioning she admits to having similar symptoms 2years previously. Clinical examination reveals no abdominal abnormality, but swollen (oedematous) skin tags are noted around the anus. Stool culture is negative. Haematological investigation shows a normochromic, normocytic anaemia. Sigmoidoscopy is performed and a mucosal biopsy is done for histological examination. The pathologist’s report states that the appearances are consistent with Crohn’s disease.

1. Which pathological features distinguish Crohn’s disease from ulcerative colitis?

2. List the complications of Crohn’s disease.

3. Why is the patient anaemic?

Case history 2

A 73-year-old man complains of passing blood and mucus per rectum. On sigmoidoscopy, a 4cm polypoid lesion is seen and part of the polyp is biopsied. The pathologist reports a villous adenoma with severe dysplasia. The sigmoid colon containing the remainder of the polyp is removed. Pathological examination of the surgical resection shows invasive adenocarcinoma.

2. Which features of colorectal adenomas are associated with a high risk of developing invasive malignancy?

3. What pathological factors are of prognostic importance in colorectal cancer?

4. Why might postoperative measurement of blood carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) be useful?

Short note questions

Write short notes on the following:

1. Carcinoid tumour.

2. Bacterial enterocolitis.

3. Colonic polyposis syndromes.

Self-assessment: answers

One best answer

2. d. Acute appendicitis is a suppurative inflammatory process in which neutrophil polymorphs predominate. Symptoms of peritonitis arise when the inflammation extends to the serosal surface of the appendix. Granulomatous inflammation is a chronic process in which macrophages and lymphocytes usually feature – a granuloma is an aggregate of several enlarged (or ‘epithelioid’) macrophages. If seen in the large bowel, granulomas suggest a number of conditions including Crohn’s disease and certain infections (such as mycobacteria and Yersinia). Carcinoid tumour does occur in the appendix and can cause obstruction with subsequent acute inflammation, but the more common initiating cause of acute appendicitis is luminal blockage by a faecolith.

True-false answers

1.

a. True. Extra-intestinal manifestations of ulcerative colitis include sclerosing cholangitis, an inflammatory disorder of bile ducts leading to multiple areas of fibrous stricture formation in the biliary system. Other associated conditions include arthritis and ocular inflammation.

b. False. Diverticular disease and colonic cancer both occur most frequently in the distal large intestine of older adults, and may coexist in individual patients. However, there is no evidence that diverticular disease increases the risk of developing malignancy (or vice versa).

c. True. Identification of C. difficile toxin in the stool of patients with suspected antibiotic-associated diarrhoea is diagnostic of pseudomembranous colitis, even in the absence of characteristic sigmoidoscopic appearances (a reddened, ulcerated colonic mucosa with multiple yellow plaques).

d. False. Coeliac disease is associated with anti-gliadin antibodies. Gliadin is a component of gluten, and treatment of coeliac disease requires removal of the offending antigen by excluding gluten from the diet. Anti-DNA antibodies are found in a number of autoimmune connective tissue diseases, particularly systemic lupus erythematosus (see Ch. 8).

e. True. Peutz–Jeghers syndrome is a rare autosomal dominant disease characterised by multiple intestinal polyps and pigmentation of mucous membranes and skin. The polyps are hamartomas (benign overgrowths of mature tissue) consisting of a smooth muscle core covered by epithelium. They arise most commonly in the small intestine but can also occur in stomach, duodenum, colon and rectum.

2.

a. False. Many colorectal cancers can be seen to arise within a pre-existing benign tumour, usually a large villous adenoma. However, malignancies occurring in patients with hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer or ulcerative colitis often develop within flat mucosa that is macroscopically normal. Patients with ulcerative colitis are followed up with regular colonoscopic investigations, at which random biopsies of the intestinal mucosa can be done for assessment of premalignant histological changes (dysplasia).

b. True. Ulceration of the luminal surface of intestinal tumours can lead to chronic blood loss. This is particularly true for proximal cancers in the caecum and ascending colon, when the blood becomes altered on passage through the bowel and the patient is unaware of the haemorrhage. Tumours arising in the sigmoid colon and rectum are more likely to alert the patient to their existence by way of fresh rectal bleeding on defecation.

c. False. Tumour stage (extent of spread) is one of the most important prognostic factors for malignant disease arising at any site. Metastasis can occur via the lymphatic system, bloodstream or across body cavities. For colorectal cancer, the absence of lymph node spread in a surgical resection specimen predicts at least a 60% chance of long-term survival, provided that local removal of the tumour is complete.

d. False. Risk factors for large intestinal carcinoma include genetic predisposition (hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer and familial polyposis coli), inflammatory bowel disease (particularly ulcerative colitis) and environmental factors (diet high in animal fat).

e. False. Over 98% of malignant colorectal neoplasms are adenocarcinomas. Squamous cell carcinoma occurs most frequently in the anal canal.

3.

b. True. Ischaemic injury to the colon may be restricted to the mucosa or extend beyond into submucosa. Chronic inflammation within the submucosa heals by fibrous scarring, which, if extensive, can lead to stricture formation.

c. True. In infants and children, often no underlying cause is identified. In adults there is a much higher likelihood of a mass lesion (tumour) causing the intussusception.

d. False. Coeliac disease is characterised by increased numbers of intra-epithelial lymphocytes in the small intestine mucosa, along with numerous plasma cells in the lamina propria. Coeliac disease is immunologically mediated, and plasma cells produce antibodies in immune reactions. Neutrophil polymorphs are the characteristic cell of acute inflammation.

e. True. Injury to the peritoneal lining of the intestine or abdominal cavity causes inflammation. The damaged tissue can undergo repair with formation of thin fibrous bands (adhesions) between bowel loops. Adhesions can follow any cause of peritonitis but are most commonly associated with previous surgery. Adhesions are a frequent cause of small intestinal obstruction.

4.

a. False. It can follow arterial occlusion, venous thrombosis or obstruction, or generalised hypoperfusion (e.g. any cause of shock).

b. True. Atherosclerosis is usually complicated by thrombosis or embolism to cause acute intestinal ischaemia.

c. False. Infarction involving the full thickness of the bowel wall often results in peritonitis and perforation.

d. False. If infarction is restricted to the mucosa, it can heal by regeneration rather than repair/fibrosis (scar tissue).

e. False. Small bowel infarction is a serious condition, and patients are often elderly with pre-existing cardiovascular disease.

Case history answers

Case history 1

1. Crohn’s disease is characterised by chronic inflammation involving all layers of the bowel wall. Fissuring ulcers, lymphoid aggregates and non-necrotising granulomas are the classical microscopic features. The disease is segmental in distribution, with intervening areas of normal bowel in between abnormal areas (‘skip lesions’). Chronic inflammation in ulcerative colitis is restricted to the mucosa. The large intestine is involved in a continuous fashion, extending proximally from the rectum.

2. Complications of Crohn’s disease include abscesses, strictures and fistula formation. Perforation, toxic dilatation and carcinoma are serious but rare complications. The terminal ileum is frequently involved in Crohn’s disease, causing diarrhoea, steatorrhoea (fat malabsorption) and general malabsorption. Anal disease (oedematous anal tags, fissure and perianal abscesses) is very common in colonic Crohn’s disease. Ulceration is often seen in the mouth. Extra-gastrointestinal manifestations include arthritis, skin lesions, biliary tract inflammation and iritis.

3. Anaemia is common in Crohn’s disease and is usually the normochromic normocytic anaemia of chronic disease, due to deficient erythropoiesis. Although the terminal ileum is often involved in Crohn’s, megaloblastic anaemia due to vitamin B12 deficiency is unusual.

Case history 2

1. Dysplasia means abnormal growth. The term is usually applied to epithelium that shows many of the cytological features of tumour cells, but without evidence of invasive malignancy. These features include hyperchromatic (darkly staining) nuclei, increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, pleomorphism (variation in the size and shape of individual nuclei and cells), increased numbers of mitotic figures (often with abnormal forms), loss of polarity (orientation) of the epithelial cells and lack of maturation of the epithelium. Dysplasia in its early stages may be reversible but many dysplastic lesions if left long enough without treatment will progress to malignancy.

2. High risk features for development of malignancy in colorectal adenomas are large size (especially >2cm), severe dysplasia and villous architecture. These features often occur together.

3. The most important pathological prognostic features are the tumour grade (the degree of differentiation) and stage (the extent of spread). The depth of invasion into the bowel wall and the presence or absence of local lymph node metastases are factors in all staging systems for colorectal cancer. Pathological assessment of the completeness of excision of a tumour in a surgical resection specimen is also an important predictor of the likelihood of achieving cure.

4. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) is a glycoprotein normally produced by gut, pancreas and liver in the embryo. It can be elevated in the serum of adults with a variety of benign and malignant diseases, including colorectal cancer. Due to the lack of specificity, measurement of blood CEA level is not a useful diagnostic test for colorectal neoplasia. However, increasing serum levels of CEA after treatment can be used as a biochemical marker of residual or recurrent disease.

Short note answers

Carcinoids are uncommon tumours with peak incidence in the sixth decade. In the gut they arise most frequently in the small intestine. Tumours appear as small masses arising in the bowel wall, with a characteristic solid yellow cut-section appearance. Histologically they are formed of uniform epithelial-like cells arranged in a variety of architectural patterns. All carcinoids are potentially malignant but behaviour depends on site of origin, depth of local invasion and tumour size. Local lymph node spread and blood-borne liver metastasis may occur. The latter can produce the carcinoid syndrome – facial flushing, diarrhoea, bronchoconstriction, cardiac valve fibrosis – due to the systemic effects of hormones (mainly serotonin) released from tumour cells. Overall 5-year survival is greater than 50%.

2. Key points regarding bacterial enterocolitis:

• it is common throughout the world, and an important cause of mortality in developing countries

• pathogenesis may be due to preformed toxins in food or toxins elaborated by bacteria multiplying within the gut

• toxins may cause symptoms by affecting gut secretion (secretory toxins) or by tissue damage (cytotoxins)

• non-toxin producing strains of bacteria cause tissue damage by direct invasion of intestinal epithelium

• common symptoms include fever, pain, diarrhoea and dysentery

• a large range of organisms may cause enterocolitis. Common examples are E. coli, Salmonella, Shigella and cholera.

3. Colonic polyposis syndromes are rare autosomally inherited diseases, characterised by multiple polyps in the large intestine, sometimes with polyps elsewhere in the gut and/or extra-intestinal manifestations. The polyps may be hamartomas (Peutz–Jeghers syndrome) or adenomas (familial polyposis coli and related conditions). It is important to identify patients with adenomatous polyposis syndromes as they are at very high risk of developing colorectal cancer, and it is necessary to screen other family members for the disease.