10 Lower Extremity Joint Injections

Lower extremity intraarticular injections with corticosteroids and anesthetics are useful treatment options for patients with hip, knee, ankle, or foot pain.4 Injections are given to treat acutely painful joints refractory to rest and oral medications. The indications, patient selection, complications,1,2,6,7,9,14,16,19 and general technique of joint injections10,25 were covered in the previous chapter. This chapter will focus on the technique of specific lower extremity intraarticular joint injections. Knowledge of multiple techniques is helpful.26

Hip Joint

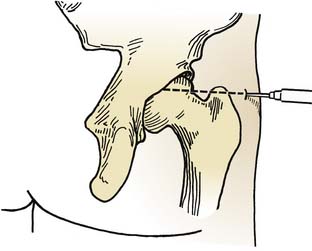

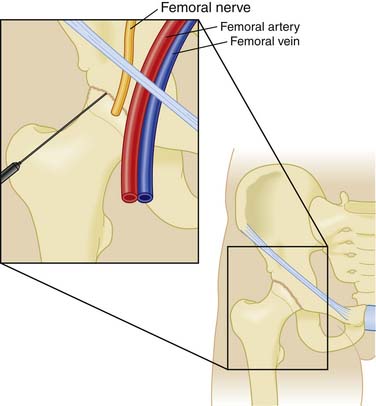

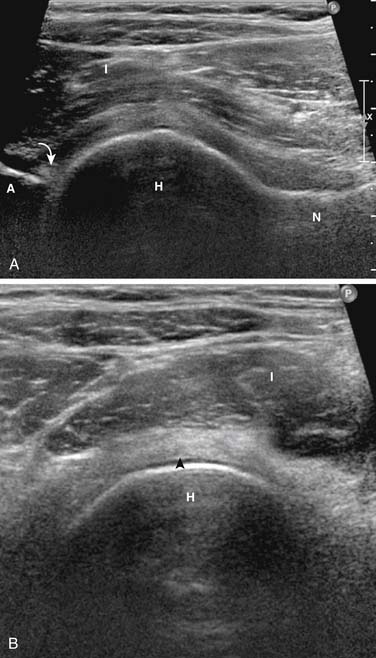

The hip joint is often difficult to infiltrate or aspirate because of its depth and the surrounding tissue. Fluoroscopic guidance with injection of contrast material or ultrasound guidance is often necessary to confirm proper needle placement. This joint may be infiltrated by an anterior or lateral approach (Figs. 10-1, 10-2, 10-3). The anterior approach is preferred.18,23,24 With the anterior approach, the patient is in the supine position with the lower extremity externally rotated. The length of the needle will depend on the patient’s size. The anatomic landmarks for the anterior approach are 2 cm distal to the anterior superior iliac spine and 3 cm lateral to the palpated femoral artery at a level corresponding to the superior margins of the greater trochanter. After superficial anesthesia is administered, the needle is advanced at an angle 60 degrees posteromedially through the tough capsular ligaments, advanced to bone, and slightly withdrawn. This technique places the tip of the needle directly into the joint, and aspiration or injection may be performed. This approach is much simpler using image guidance to direct the needle posteromedially into the joint. When the capsular ligaments have been penetrated, 2 to 4 mL of anesthetic and corticosteroid suspension may be introduced.

Knee

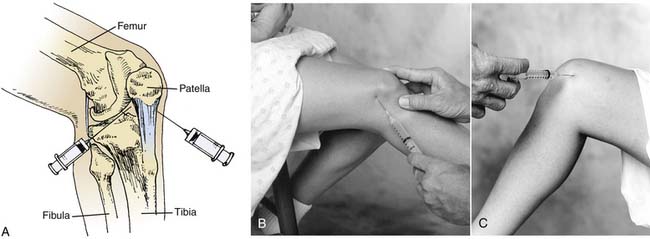

The knee is the most commonly aspirated and injected joint in the body. It contains the largest synovial space and demonstrates the most visible and palpable effusion (when present). A patient is usually most comfortable lying supine with sufficient pillows. The knee is prepared using an aseptic technique. If a large effusion is present, whether medially or laterally, the site of entry should be over the maximal expansion of the effusion in order to cause the least discomfort during the procedure. For injections in which a large effusion is not present, the lateral, medial, suprapatellar, or anterior approach may be used (Fig. 10-4). Before injecting or aspirating the knee, the patella should be grasped between the examiner’s thumb and forefinger and rocked gently from side to side to ensure that the patient’s muscles are relaxed.

If a large effusion is present, the suprapatellar approach may be used. This does not have any specific advantage over the lateral approach unless the effusion is expanding the suprapatellar bursa. The needle is introduced at the point of maximal expansion of the effusion, and the joint is then aspirated. This approach is usually not as good as the lateral approach if the knee is to be injected only and not aspirated. It is much easier to enter the joint space with the medial or lateral approach.

On occasion, an anterior approach to the knee may be desired if a patient cannot fully extend the knee. In these cases, the patient may be sitting or supine with the knee flexed to 90 degrees. The needle is inserted just inferior to the inferior patellar pole from either the lateral or medial side of the patellar tendon. The needle is then advanced parallel to the tibial plateau until the joint space is entered. It is more difficult to aspirate a knee effusion when using this approach.23 Moreover, the risk of puncturing the articular cartilage is much higher, as is the risk to the infrapatellar fat pad. Occasionally, the knee is approached anteriorly by inserting the needle directly through the patellar tendon. This approach has no merit because it increases discomfort to the patient and may cause bleeding in the patellar ligament.

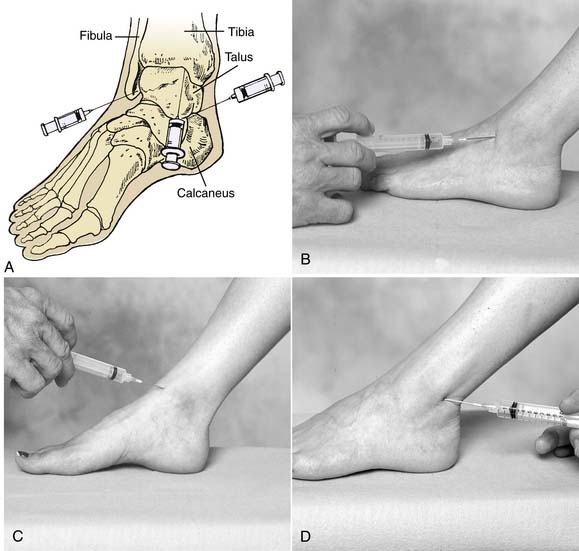

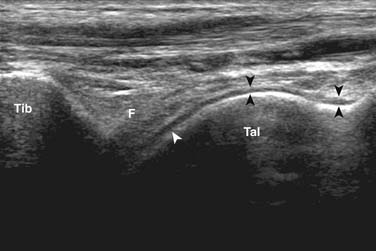

Ankle Mortise

The ankle joint is not commonly injected; however, it may be subject to osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, or chronic pain resulting from instability.8,12,13,27,28 An anterior medial or anterior lateral approach may be used, depending on the location of pain or pathologic process (Figs. 10-5 and 10-6). For the medial approach, a slight depression is felt between the extensor hallucis longus tendon laterally and tibialis anterior tendon medially on the inferior border of the tibia superiorly and the talus inferiorly. The needle is then directed slightly laterally and perpendicular to the tibial joint surface. The talus has a superior curve, and the needle may need to be angled slightly superiorly to avoid contact with the talar joint surface.

The lateral approach is useful in situations in which pathologic processes in the ankle appear to be most prominent either at the talofibular joint or the tibiotalar joint. Here, the foot is placed in moderate plantar flexion. The area enclosed by the tibia superiorly, the talus inferiorly, and the fibular head laterally is palpated. The extensor tendons of the toes should be medial to the injection site. The needle is then inserted from an anterolateral position and is directed toward the posterior edge of the medial malleolus. If the joint surface is encountered, the physician should direct the needle slightly upward, remembering that the talar dome arches superiorly.

Subtalar Joint

Occasionally, the subtalar joint is the site of a pathologic process.3 The easiest approach to this joint is to have the patient lie prone with his or her feet extending over the end of the examination table. This allows the ankle to be in the neutral position. The posterior and lateral portions of the ankle are then prepared aseptically. The site of entry for the injection is along a line drawn from the most prominent portion of the distal fibula posterior to the Achilles tendon. This line should be parallel to the plantar aspect of the foot with the foot in neutral position; halfway between the prominent aspect of the lateral malleolus and the Achilles tendon, the needle is inserted and directed toward a point inferior and medial to the medial malleolus. Fluoroscopic or ultrasound guidance can be very helpful during subtalar joint injections.5.11,15,17

Metatarsophalangeal Joints

The metatarsophalangeal joints are most frequently infiltrated with a dorsal approach (Fig. 10-7). This approach is carried out by palpating the metatarsophalangeal margins with plantar flexion of the toe to facilitate insertion of the needle. The needle is then advanced into the joint. The first metatarsophalangeal joint is frequently affected by arthritic conditions and gout. When a swollen joint is encountered, infiltration and aspiration may be easier with a swollen capsule.

1. Bliddal H., Qvistgaard E., Terslev L., et al. A randomized, controlled study of a single intra-articular injection of etanercept or glucocorticosteroids in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2006;35(5):341-345.

2. Hajjioui A., Nys A., Poiraudeau S., Revel M. An unusual complication of intra-articular injections of corticosteroids: Tachon syndrome. Two case reports. Ann Readapt Med Phys. 2007;50(9):721-723.

3. Shortt C.P., Morrison W.B., Roberts C.C., et al. Shoulder, hip, and knee arthrography needle placement using fluoroscopic guidance: Practice patterns of musculoskeletal radiologists in North America. Skeletal Radiol. 2009;38(4):377-385.

4. Pfenninger J.L. Infections of joints and soft tissue: Part I. General guidelines. Am Fam Physician. 1991;44:1196-1202.

5. Beukelman T., Arabshahi B., Cahill A.M., et al. Benefit of intraarticular corticosteroid injection under fluoroscopic guidance for subtalar arthritis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(11):2330-2336.

6. Cahill A.M., Cho S.S., Baskin K.M., et al. Benefit of fluoroscopically guided intraarticular, long-acting corticosteroid injection for subtalar arthritis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37(6):544-548.

7. Henning T., Finnoff J.T., Smith J. Sonographically guided posterior subtalar joint injections; Anatomic study and validation of 3 approaches. PM R. 2009;1(10):925-931.

8. Khosla S., Thiele R., Baumhauer J.F. Ultrasound guidance for intra-articular injections of the foot and ankle. Foot Ankle Int. 2009;30(9):886-890.

9. Kirk K.L., Campbell J.T., Guyton G.P., Schon L.C. Accuracy of posterior subtalar joint injection without fluoroscopy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(11):2856-2860.

10. Hasegawa M., Nakoshi Y., Tsujii M., et al. Changes in biochemical markers and prediction of effectiveness of intra-articular hyaluronan in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16(4):526-529.

11. Gray R.G., Gottlieb N.L. Rheumatic disorders associated with diabetes mellitus: Literature review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1976;6:19-34.

12. Hollander J.L. Intrasynovial corticosteroid therapy in arthritis. Md State Med J. 1970;19:62-66.

13. Hollander J.L. Joint problems in the elderly: How to help patients cope. Postgrad Med. 1988;84:209-211. 215216

14. Jalava S. Periarticular calcification after intra-articular triamcinolone hexacetonide. Scand J Rheumatol. 1980;9:190-192.

15. Gray R.G., Tenenbaum J., Gottlieb N.L. Local corticosteroid injection treatment in rheumatic disorders. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1981;10:231-245.

16. Kothari T., Reyes M.P., Brooks N., et al. Pseudomonas cepacia septic arthritis due to intra-articular injections of methylprednisolone. Can Med Assoc J. 1977;116:1230-1235.

17. Balch H.W., Gibson J.M., El-Ghobarey A.F., et al. Repeated corticosteroid injections into knee joints. Rheumatol Rehabil. 1977;16:137-140.

18. Leversee J.H. Aspiration of joint and soft tissue injections. Prim Care. 1986;13:579-599.

19. McCarty D.J., McCarthy G., Carrera G. Intra-articular corticosteroids possibly leading to local osteonecrosis and marrow fat-induced synovitis. J Rheumatol. 1991;18:1091-1094.

20. Owen D.F. Intra-articular and soft tissue aspiration injection. Clin Rheumatol Pract (Mar-May). 1986:52-63.

21. Peterson C., Hodler J. Evidence-based radiology (Part 2): Is there sufficient research to support the use of therapeutic injections into the peripheral joints? Skeletal Radiol. 2010;39(1):11-18.

22. Perrot S., Laroche F., Poncet C., et al. Are joint and soft tissue injections painful? Results of a national French cross-sectional study of procedural pain in rheumatological practice. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11(1):16.

23. Adleberg J.S., Smith G.H. Corticosteroid-induced avascular necrosis of the talus. J Foot Surg. 1991;30:66-69.

24. Pfenninger J.L. Injections of joints and soft tissues: Part II. Guidelines for specific joints. Am Fam Physician. 1991;44:1690-1701.

25. Shimizu M., Higuchi H., Takagishi K., et al. Clinical and biochemical characteristics after intra-articular injection for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: Prospective randomized study of sodium hyaluronate and corticosteroid. J Orthop Sci. 2010;15(1):51-56.

26. Gordon G.V., Schumacher H.R. Electron microscopic study for depot corticosteroid crystals with clinical studies after intra-articular injection. J Rheumatol. 1979;6:7-14.

27. Stefanich R.J. Intra-articular corticosteroids in treatment of osteoarthritis. Orthop Rev. 1986;15:65-71.

28. Wilke W.S., Tuggle C.J. Optimal techniques for intra-articular and peri-articular joint injections. Mod Med. 1988;56:58-72.