Lower extremity block: Psoas compartment block

Relevant anatomy

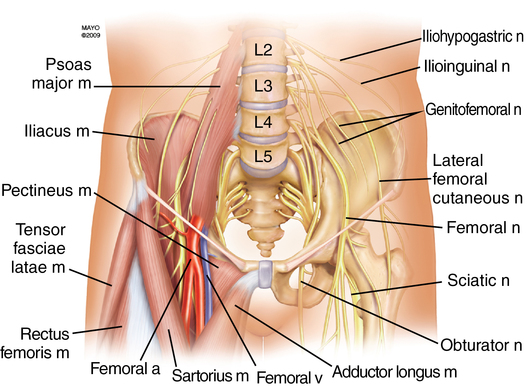

The lumbar plexus is most commonly formed from the ventral rami of L1 through L4, although frequently a branch of T12 and, occasionally, a branch from L5 are included. The plexus lies anterior to the transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae and descends vertically with the psoas muscle. The branches of the lumbar plexus emerging from the psoas muscle are the femoral nerve (L2-L4), obturator nerve (L2-L4), lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (L2-L3), iliohypogastric nerve (L1), ilioinguinal nerve (L1), and genitofemoral nerve (L1-L2) (Figure 128-1). It provides sensory innervation to the anterior thigh and to the medial portion of the lower leg via the saphenous nerve (distal branch of the femoral nerve), as well as the majority of the femur, ischium, and ilium.

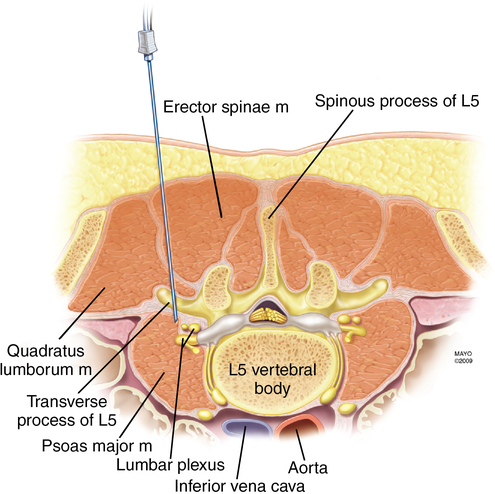

As the needle passes from posterior to anterior at the level of L4 through L5, the following structures are encountered: skin, subcutaneous adipose tissue, posterior lumbar fascia, paraspinous muscles, anterior lumbar fascia, quadratus lumborum, and the psoas muscle (Figure 128-2). The distance from skin to lumbar plexus varies greatly with sex and body mass index, whereas the distance from the transverse process of L4 to the lumbar plexus consistently ranges from 1.5 to 2.0 cm in both sexes.

Technique

Patient position

Needle insertion site

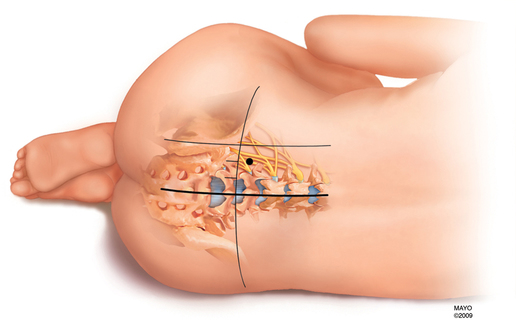

One of several needle insertion sites can be used, although the landmarks described by Capdevila and colleagues use localization of the L4 transverse process, thereby reducing the likelihood of excessive needle depth. The intercristal line is identified and drawn. A horizontal line is drawn identifying the midline. A line originating at the PSIS is drawn parallel to midline. The distance between the PSIS and midline is dissected into thirds. The needle insertion site is 1 cm cephalad to the intercristal line at the junction of the lateral one-third line and the medial two-thirds line (Figure 128-3).