Langerhans cell histiocytosis

First-line therapies

Second-line therapies

Third-line therapies

Lenalidomide induced therapeutic response in a patient with aggressive multi-system Langerhans cell histiocytosis resistant to 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine and early relapse after high dose BEAM chemotherapy with autologous peripheral stem cell transplant.

Adam Z, Rehak Z, Koukalova R, Szturz P, Krejci M, Pour L, et al. Vnitr Lek 2012; 58: 62–71.

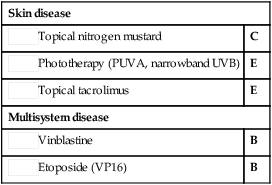

Topical nitrogen mustard

Topical nitrogen mustard Phototherapy (PUVA, narrowband UVB)

Phototherapy (PUVA, narrowband UVB) Topical tacrolimus

Topical tacrolimus Vinblastine

Vinblastine Etoposide (VP16)

Etoposide (VP16)

Prednisolone

Prednisolone 6-Mercaptopurine

6-Mercaptopurine Thalidomide

Thalidomide Methotrexate

Methotrexate Cytosine arabinoside (Ara-C)

Cytosine arabinoside (Ara-C) 2-Chlorodeoxyadenosine (2-CdA)

2-Chlorodeoxyadenosine (2-CdA) Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy Cyclosporine

Cyclosporine Bone marrow transplantation

Bone marrow transplantation Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole Interferon-α

Interferon-α 2-Deoxycoformycin

2-Deoxycoformycin Interleukin-2

Interleukin-2 Isotretinoin

Isotretinoin Acitretin

Acitretin Lenalidomide

Lenalidomide Photodynamic therapy

Photodynamic therapy Clofarabine

Clofarabine Mistletoe

Mistletoe