Chapter 166 Interspinous Bumpers

Lumbar stenosis is defined as the reduction in the diameter of the spinal canal, lateral recess, and/or neural foramina. Stenosis is most frequently a sequela of the degenerative process of aging, but recently genetic factors have been demonstrated to play a significant role.1–3 The degenerative changes of disc desiccation with anular bulging, osteophyte formation, ligamentum hypertrophy, facet hypertrophy, and/or facet joint cyst all contribute to reducing the space available to the cauda equina and causing the classic symptoms of neurogenic claudications. In particular, compression and ischemia of nerve roots are the main source for this type of pain.4–6

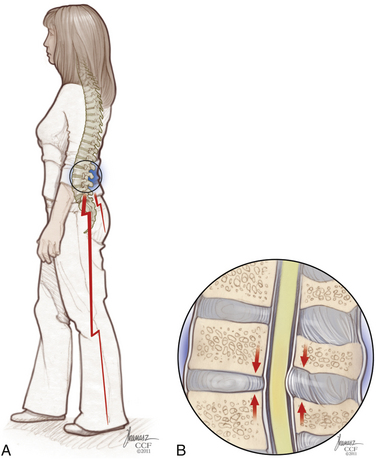

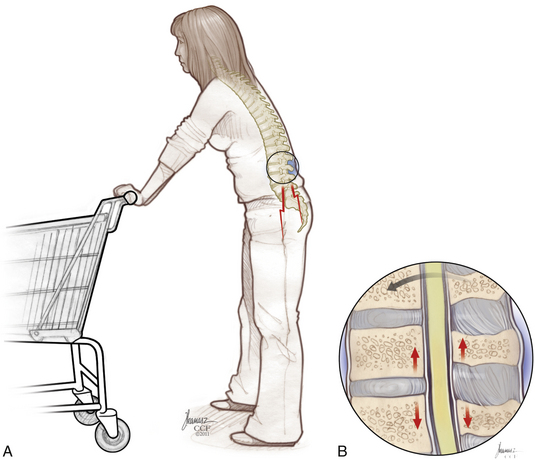

Patients with the classic presentation of intermittent neurogenic claudication have buttock and leg pain when they stand and walk and have relief of symptoms when they flex forward, as when pushing a shopping cart, or when they sit or lie down (Figs. 166-1 and 166-2). This results mainly from the buckling of the ligamentum flavum and a decrease in the size of the central canal, subarticular region, and foraminal area with standing and walking.

The presence of canal stenosis on radiographic imaging does not itself define the syndrome, as there is a poor correlation between the degree of stenosis and the severity of symptoms.7,8

Interspinous Spacers: Indications and Contraindications

It should be noted that in the United States the primary use of these interspinous devices is for the treatment or stabilization of the lumbar spine to correct neurogenic claudication caused by canal stenosis. There is biomechanical evidence of unloading the facet joints and disc space,9 which theoretically may limit back pain associated with a degenerative lumbar segment. In other areas of the world, these devices are used primarily to treat lumbar axial pain, as opposed to neurogenic claudication.

Wallis Interspinous Spacer

In 1986 Sénégas10 developed the first lumbar interspinous implant designed to stiffen unstable operated degenerative segments without eliminating mobility. At first called the Mechanical Normalization System, it included a titanium interspinous blocker and an artificial ligament made of Dacron.

Between 1988 and 1993, more than 300 patients were treated for degenerative conditions with this first-generation device. It was concluded that many patients demonstrated significant resolution of residual low-back pain.11

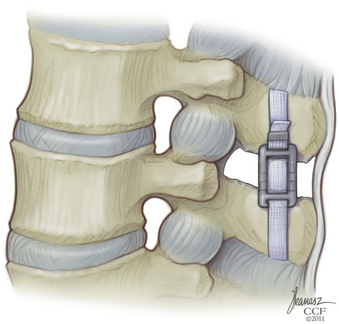

The Wallis System (Abbott Spine, S.A., Bordeaux, France) was the second-generation interspinous spacer. The crucial change was in material properties. The Wallis spacer is made of polyetheretherketone (PEEK), a strong, completely radiolucent material compatible with MRI. This plastic-like polymer is more elastic, which reduces the risk of spinous process stress fractures. In addition, the Wallis device has notches that fit the physiologic shape of the lumbar spine, which minimizes the need for bone resection and avoids constraint on bone.

Surgical Technique

The surgical technique for the Wallis interspinous spacer was initially described by Sénégas.12 The procedure is typically performed under general anesthesia with the patient in a prone position on a radiolucent operating table. The patient’s lumbar midline should be marked before he or she is positioned. A neutral position of physiologic lumbar lordosis is best to optimize the effect of the implant.

The supraspinous ligament is returned to its original position and reinserted onto each spinous process with a single silk suture passed through a hole made in the spinous process (Fig. 166-3).

X-STOP Interspinous Spacer

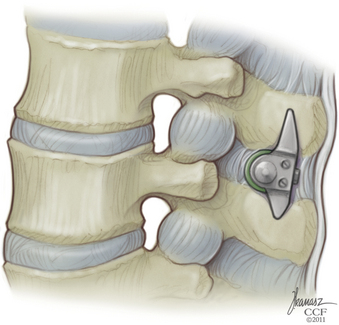

The X-STOP (Kyphon, Medtronic, Sunnyvale, CA) interspinous process decompression (IPD) device is a two-component oval titanium implant that fits between the spinous processes of the lumbar spine. A newer version has a PEEK sleeve over the titanium insert. Several clinical studies have shown the efficacy of the X-STOP device in treating neurogenic claudication secondary to lumbar stenosis.13–16

Surgical Technique

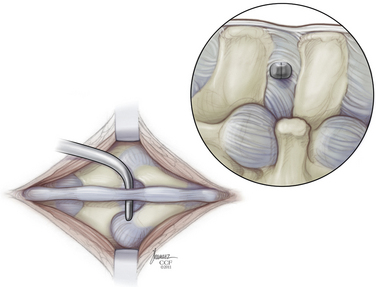

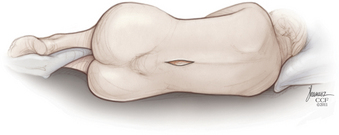

The implant procedure for this device can be done after induction of light sedation or general anesthesia. The patient is placed on a radiolucent table in a right lateral decubitus position; afterward the patient is asked to flex or assume a knee-chest position (Fig. 166-4). The level to be treated is identified by fluoroscopy; localization is at the interspinous level, not the disc space level.

FIGURE 166-4 We prefer to place the implant with the patient positioned in the lateral decubitus position.

(Copyright Cleveland Clinic Foundation.)

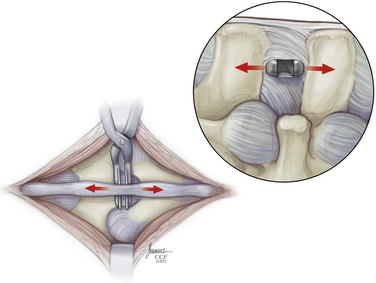

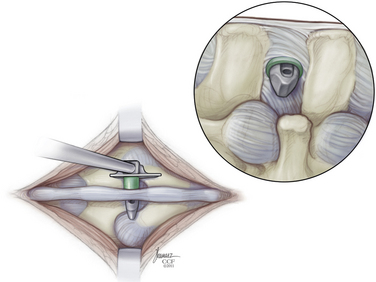

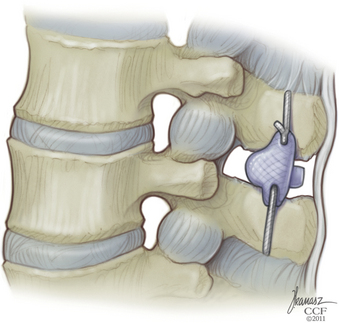

The paraspinal muscles are lifted subperiosteally from the spinous processes using a Cobb retractor and/or electrocautery, and all midline structures are left intact. The small curved dilator is inserted across the interspinous space through the most ventral margin of the interspinous ligament (Fig. 166-5). The curved dilator is removed. A sizing distractor is then inserted between the spinous processes and expanded until the supraspinous ligament is taut, which is verified by palpation of the ligament (Fig. 166-6). The correct implant size is indicated on the sizing dilator.

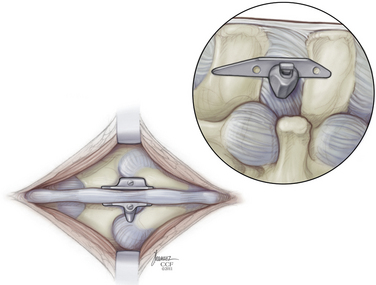

The appropriate X-STOP device is then placed between the spinous processes to the point where the wing is flush with the right side of the spinous process (Fig. 166-7). Fluoroscopy should verify the correct level and ventral placement. If the device appears to be placed too far dorsally, the facet will need to be trimmed. The two wings are approximated medially and the universal wing screw is secured (Fig. 166-8). The incision is then irrigated and closed in standard fashion (Fig. 166-9).

DIAM Interspinous Spacer

The DIAM Spinal Stabilization System (Medtronic, Sofamor Danek, Memphis, TN) is a soft interspinous spacer. The core is made of silicone, which is covered by a polyethylene coating. The DIAM implant was developed by Jean Taylor.17 It is a dorsal interspinal dynamic stabilization or balancing device. The DIAM is thought to work by reducing loading of the disc, restoring the dorsal tension band, realigning the facet joint line, and increasing foraminal height. But, few articles on the efficacy of this product have appeared in the literature.18,19

Surgical Technique

In the ligament-sacrificing procedure, the supraspinous and interspinous ligaments are removed at the level of interest for DIAM implantation. The interspinous space is then prepared by squaring it off with a rongeur. The space is then distracted, and measuring trials are used to determine the size of the DIAM. The implant is inserted and seated with a tamp and mallet. It is secured in place with two laces, one around the spinous process above, and another around the one below, the DIAM is then tightened and crimped. The wound is irrigated and closed in the standard fashion. No postoperative immobilization is required (Fig. 166-10).

Outcomes

Anatomy and Biomechanics

Richards et al.20 published the effect of the X-STOP spacer on the spinal canal, subarticular diameter, and foraminal height with and without the implant. With the device in place, the canal area was found to be increased by 18%, the diameter by 10%, and the subarticular diameter by 50%. The foraminal area was found to be increased by 25%, and the width increased by 41%.

Wilke et al.21 evaluated in vitro the biomechanical segmental stability and intradiscal pressure achieved with the four different interspinous implants (i.e., Coflex, Wallis, DIAM, and X-STOP). Interestingly, the effect on the flexibility of all the treated segments is similar, despite the variations of implant design—referred to the neutral position of the intact segments, each device significantly stabilized and unloaded the disc in extension, but had little effect on range of motion (ROM) and intradiscal pressure in flexion, lateral bending, and axial rotation.

In 2008 Schulte et al.22 studied biomechanically the effect of spinal decompression alone, as well as in conjugation with semirigid stabilizing implants (Wallis, Dynesys) on the ROM of lumbar spine segments. Undercutting decompression leads to a significant segmental instability in all planes. Implantation of Wallis or Dynesys spacers after decompression leads to a significant restriction of segmental ROM. The Wallis device limits only the flexion-extension plane; the Dynesys limits both flexion-extension and lateral bending. Axial rotation is minimally restricted by both implants. The observed effects on the neutral zone correspond well with the effects on ROM.

Clinical Outcomes

X-STOP

One- and 2-year outcomes utilizing the X-STOP device were published by Zucherman et al.14,15 There were multicenter, randomized controlled studies for the treatment of lumbar canal stenosis with the X-STOP implant. The implant was directly compared with the best conservative care, usually involving epidural steroid injection. At 1 year, the success rate was 59% with X-STOP compared with 12% for nonoperative therapy. Six patients in the X-STOP group and 24 in the control cohort underwent decompressive laminectomy. Interestingly, the results following laminectomy were similar to those of the remainder of the X-STOP patients. At 2 years, 73.1% of patients were satisfied with their outcome compared with those who underwent conservative therapy (35.9%).

It also appears that the device is effective for treating spondylolisthesis. Anderson et al.23 published a randomized controlled study in patients with neurogenic claudication secondary to degenerative spondylolisthesis. They concluded that the X-STOP device was more effective than nonoperative treatment. There was no increase in the degree of spondylolisthesis postoperatively. These data are appealing for the treatment of those patients who are not felt to be candidates for a fusion following decompression.

The durability of the X-STOP device has not been well defined. Kondrashov et al.24 demonstrated the success rate among patients treated with X-STOP devices at one and two levels was 78% at a mean of 4.2 years postoperatively, which is consistent with the intermediate-term (1 and 2 years) results of Zucherman et al.14,15 This indicates that the long-term durability is at least 4 years; unfortunately not many people were followed out to 4 years for the purpose of this study.

A recent study has shown slightly less promise than the aforementioned manuscripts.25 Although 71% of patients reported satisfaction with the procedure, only 54% of patients reported clinically significant improvement in their symptoms. Twenty-nine percent of patients required caudal epidural steroid injection 12 months after surgery for recurrence of symptoms.

Wallis

The Wallis device has not been approved by the FDA for use in the United States. Despite this, long-term analysis has been reported regarding its use outside the United States. In 2009 Sénégas et al.26 published a long-term retrospective clinical survey on 107 patients with canal stenosis or herniated disc, or both, who underwent lumbar dynamic stabilization with the Wallis system. One hundred thirty-three were alive at the time of analysis, but only 107 filled out the questionnaire. The average follow-up was 13.5 years. Twenty-three patients underwent a subsequent lumbar procedure, with 20 having the implant removed and fusion performed. The other three had surgery at adjacent levels. At an average of 13 years postprocedure, 95% of patients reported they were very satisfied or satisfied with the implant, and the same was seen in only 65% following fusion. There are many weaknesses of this manuscript, but it does lend credence to the long-term durability and clinical utility of the implant. It remains unclear, however, who is the most appropriate patient to utilize the device.

DIAM

Similar to the Wallis device, the DIAM implant is not currently FDA approved for use in the United States. It has been used extensively in other countries for the treatment of a variety of lumbar pathologies. One comparative study was published evaluating the use of DIAM following simple lumbar discecotmy.27 Sixty-two patients underwent lumbar laminectomy and/or discectomy; 31 of these patients underwent concomitant placement of the DIAM device (33 devices total). At an average of 12 months following surgery no significant differences were noted between groups, using the VAS and McNab outcomes scales. There were three device failures noted in the DIAM group, two transverse process fractures and one infection. It appears that the device did not alter the sagittal alignment or disc height following placement; however, it did not improve outcome as well. What remains unclear in comparative studies is how the device may affect the treatment of other lumbar degenerative diseases, such as mechanical pain and pseudoclaudication. Certainly further research is warranted at this time.

Anderson P.A., Tribus C.B., Kitchel S.H. Treatment of neurogenic claudication by interspinous decompression: application of the X-STOP device in patients with lumbar degeneration spondylolisthesis. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006;4:463-471.

Kirkaldy-Willis W.H., Wedge J.H., Yong-Hing K., et al. Pathology and pathogenesis of lumbar spondylosis and stenosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1978;3:319-328.

Lindsey D.P., Swanson K.E., Fuchs P., et al. The effects of an interspinous implant on the kinematics of the instrumented and adjacent levels in the lumbar spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28:2192-2197.

Sénégas J., Vital J.M., Pointillart V., et al. Long-term actuarial survivorship analysis of an interspinous stabilization system. Eur Spine J. 2007;16:1279-1287.

Sénégas J., Vital J.M., Pointillart V., et al. Clinical evaluation of a lumbar interspinous dynamic stabilization device (the Wallis system) with a 13-year mean follow-up. Neurosurg Rev. 2009;32:335-342.

Zucherman J.F., Hsu K.Y., Hartjen C.A., et al. A prospective randomized multi-center study for the treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis with the X-STOP interspinous implant: 1-year results. Eur Spine J. 2004;13:22-31.

Zucherman J.F., Hsu K.Y., Hartjen C.A., et al. A multicenter, prospective, randomized trial evaluating the X-STOP interspinous process decompression system for the treatment of neurogenic intermitent claudication: two-year follow-up results. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:1351-1358.

1. Kirkaldy-Willis W.H., Wedge J.H., Yong-Hing K., et al. Pathology and pathogenesis of lumbar spondylosis and stenosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1978;3:319-328.

2. Yong-Hing K., Kirkaldy-Willis W.H. The pathophysiology of degenerative disease of the lumbar spine. Orthop Clin North Am. 1983;14:491-504.

3. Battie M.C., Videman T., Parent E. Lumbar disc degeneration: epidemiology and genetic influences. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29(23):2679-2690.

4. Dejerine J. La claudication intermittente de la moelle épinière. Presse Med. 1911;19:981-984.

5. Blau J.N., Logue V. Intermittent claudication of the cauda equina. An unusual syndrome resulting from central protrusion of a lumbar intervertebral disc. Lancet 1:. 1961:1081-1086.

6. Wakamatsu E. Clinical features of degenerative lumbar stenosis and indication of operation. J Jpn Orthop Assoc. 1984;58:S42-S43.

7. Boden S.D., McCowin P.R., Davis D.O., et al. Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the cervical spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1990;72:1178-1184.

8. Boden S.D., Davis D.O., Dina T.S., et al. Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1990;72:403-408.

9. Lindsey D.P., Swanson K.E., Fuchs P., et al. The effects of an interspinous implant on the kinematics of the instrumented and adjacent levels in the lumbar spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28:2192-2197.

10. Sénégas J. Mechanical supplementation by non-rigid fixation in degenerative intervertebral lumbar segments: the Wallis system. Eur Spine J. 2002;11(Suppl 2):S164-S169.

11. Sénégas J., Vital J.M., Pointillart V., et al. Long-term actuarial survivorship analysis of an interspinous stabilization system. Eur Spine J. 2007;16:1279-1287.

12. Sénégas J. Dynamic lumbar stabilization with the Wallis interspinous implant. Interact Surg. 2008;3:221-228.

13. Hero A., Saari T., Suomalainen O., et al. The degree of decompressive relief and its relation to clinical outcome in patients undergoing surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24:1010-1014.

14. Zucherman J.F., Hsu K.Y., Hartjen C.A., et al. A prospective randomized multi-center study for the treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis with the X-STOP interspinous implant: 1-year results. Eur Spine J. 2004;13:22-31.

15. Zucherman J.F., Hsu K.Y., Hartjen C.A., et al. A multicenter, prospective, randomized trial evaluating the X-STOP interspinous process decompression system for the treatment of neurogenic intermitent claudication: two-year follow-up results. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:1351-1358.

16. Kuchta J., Sobottke R., Eysel P., et al. Two-year results of interspinous spacer (X-Stop) implantation in 175 patients with neurologic intermittent claudication due to lumbar spinal stenosis. Eur Spine J. 2009;18(6):823-829.

17. Mariottini A., Pieri S., Giachi S., et al. Preliminary results of a soft novel lumbar intervertebral prosthesis (DIAM) in the degenerative spinal pathology. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2005;92:129-131.

18. Minns R.J., Walsh W.K. Preliminary design and experimental studies of a novel soft implant for correcting sagittal plane instability in the lumbar spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997;22:1819-1827.

19. Christie S.D., Song J.K., Fessler R.G. Dynamic interspinous process technology. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30(Suppl 16):S73-S78.

20. Richards J.C., Majumdar S., Lindsey D.P., et al. The treatment mechanism of an interspinous process implant for lumbar neurogenic intermittent claudication. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:744-749.

21. Wilke H.J., Drumm J., Haussler K., et al. Biomechanical effect of different lumbar interspinous implants on flexibility and intradiscal pressure. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:1049-1056.

22. Schulte T.L., Hurschler C., Haversath M., et al. The effect of dynamic, semi-rigid implants on the range of motion of lumbar motion segments after decompression. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:1057-1065.

23. Anderson P.A., Tribus C.B., Kitchel S.H. Treatment of neurogenic claudication by interspinous decompression: application of the X-STOP device in patients with lumbar degeneration spondylolisthesis. J Neurosurg Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;4:463-471.

24. Kondrashov D.G., Hannibal M., Hsu K.Y., et al. Interspinous process decompression with the X-STOP device for lumbar spinal stenosis: 4 year follow-up study. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2006;19:323-327.

25. Siddiqui M., Smith F.W., Wardlaw D. One-year results of X-Stop interspinous implant for the treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:1345-1348.

26. Sénégas J., Vital J.M., Pointillart V., et al. Clinical evaluation of a lumbar interspinous dynamic stabilization device (the Wallis system) with a 13-year mean follow-up. Neurosurg Rev. 2009;32:335-342.

27. Kim K.A., McDonald M., Pik J.H.T., et al. Dynamic intraspinous spacer technology for dorsal stabilization: case-control study on the safety, sagittal angulation, and pain outcome at 1-year follow-up evaluation. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;22(1):E7.