31 Intercostal Nerve Block

Anatomy of Intercostal Nerves

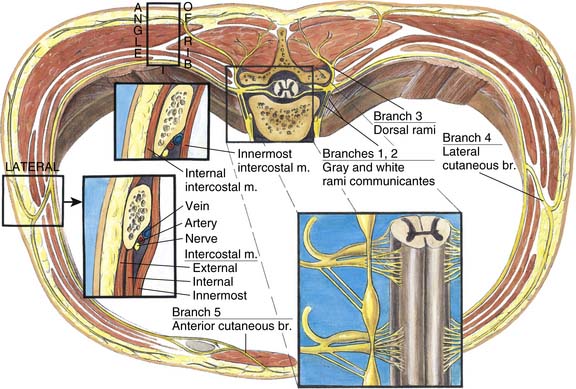

The twelve pairs of thoracic spinal nerves (T1-12) are divided into ventral and dorsal rami after they pass through the intervertebral foramina. The ventral rami of T1-T11 form the intercostal nerves that enter the intercostal spaces. The ventral ramus of T12 forms the subcostal nerve that is located inferior to the 12th rib. The dorsal rami of T1-T12 pass posteriorly to supply sensation to skin, muscles, and bones of the back.1

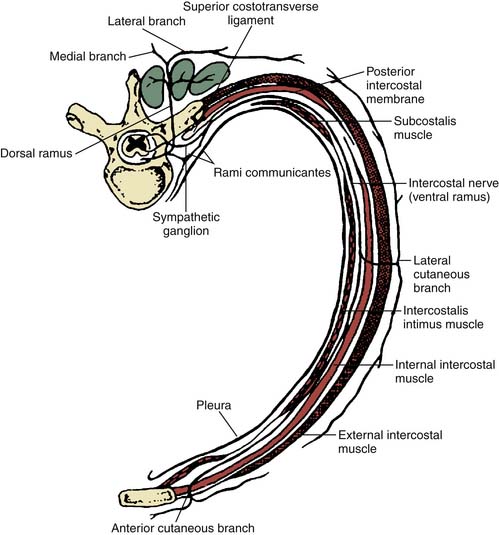

Intercostal nerves are composed of dorsal horn sensory afferent fibers, ventral horn motor efferent fibers, and postganglionic sympathetic nerves. The major branches of intercostal nerves are anterior and lateral cutaneous branches (Fig. 31-1). These branches divide and innervate the skin and intercostal muscles of an individual segment along with variable collateral innervation of the adjacent segments. Because of such collateral innervation, it is necessary to block a level above and below the desired level when an intercostal nerve block is performed.

Figure 31-1 Anatomy of an intercostal nerve.

(Adapted from Ferrante FM, VadeBoncouer TR: Postoperative Pain Management. New York, Churchill Livingstone, 1993. Elsevier.)

Throughout its course, each intercostal nerve is associated with an artery and a vein. The intercostal arteries are derived directly from the aorta. The intercostal veins are derived from the confluence of venules along the chest and end in the azygous and hemiazygous veins. The intercostal nerve travels inferior to the vein and artery of the same segment (Fig. 31-2).

Technique

The insertion site for an intercostal nerve block is usually just below the lower edge of the rib, slightly medial to the posterior axillary line, and 6 to 8 cm lateral to the respective vertebral spinous process. If the insertion site is too anterior, the lateral cutaneous branch of the intercostal nerve may be missed as it arises at the midaxillary line (see Fig. 31-1).

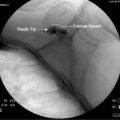

Fluoroscopic guidance is recommended, but not absolutely necessary for performing intercostal nerve blocks. Under sterile conditions, a skin wheal is made with local anesthesia. A 3.5 inch, 25- (or 22-) gauge needle is inserted over the rib and directed perpendicular to the skin. A 15-degree bend away from the bevel of the needle allows the needle to “steer” (bevel is pointing caudad). Longer needles may be needed for obese patients. When the needle contacts the periosteal surface of the inferior portion of the rib bone, it can be rotated 180 degrees, then slowly “walked off” the rib inferiorly until it just slips off under the rib. The 15-degree bend of the needle tip away from the bevel can facilitate the needle being walked off the rib, with the direction of the bevel cephalad, which then places the bevel of the needle in proximity to the intercostal nerve, (Figs. 31-3 through 31-5) where it is known to lie in the intercostal groove as the classic VAN complex (vein, artery, nerve from cephalad to caudad) (see Fig. 31-2). Another helpful technique is to manually retract the skin superiorly prior to needle insertion, which allows the needle to automatically move inferior when the needle contacts bone. This maneuver reduces needle motion and rotation.2 When the lower rib margin is identified, the needle is then advanced 2 to 3 mm to reach the intercostal groove. After negative aspiration for blood and air, a mixture of 1 to 5 mL of lidocaine or bupivacaine with or without 1: 200,000 epinephrine and/or corticosteroid is injected. The procedure can be repeated in other intercostal segments. Due to collateral innervation, blockade of at least three adjacent segments is often needed to ensure anesthesia/analgesia in the distribution of the middle intercostal nerve.

Figure 31-3 Needle placement in right T12 intercostal groove after “walking off” inferior edge of T12 rib.

To perform a continuous intercostal nerve block, a catheter is placed through a 17-gauge epidural needle. The insertion site is the same as for a single injection, that is, below the lower edge of the rib, close to the posterior axillary line, and 6 to 8 cm lateral to the respective vertebral spinous process. To obtain maximal coverage, the insertion site should be in the middle of the segments to be blocked. The bevel of the Touhy needle is oriented medially and the tip of epidural catheter is directed medially. After 10 mL of anesthetic solution is injected through the epidural needle, an intercostal catheter is advanced 2 cm and then secured to the skin.3 Appropriate spread of local anesthetics can be confirmed by radiographic imaging with the use of a nonionic contrast agent prior to local anesthetic injection to rule out subarachnoid, intravascular, or pleural placement.

Complications

The incidence of clinical significant pneumothorax has been reported less than 0.1%.4,5 Careful attention to technique, smaller-gauge needles, use of fluoroscopic guidance, and avoidance of vigorous needle advancement or probing may help decrease the incidence of this complication.

Accidental intravascular injection of local anesthetics during intercostal block is uncommon but potentially serious. It is known that blood levels of local anesthetics after an intercostal nerve block are significantly greater than those after other frequently performed regional anesthetic techniques.6 Adding epinephrine to local anesthetics and aspirating for blood before administering anesthetics, as well as injection of nonionic contrast under continuous fluoroscopy, are important steps that can be taken to minimize intravascular injection of local anesthetics.

Other rare complications associated with an intercostal nerve block include infection, hemothorax, hemoptysis, hematoma, tissue necrosis, neuritis, respiratory insufficiency, subarachnoid block, failed block, and allergic reaction to local anesthetics.7 If nonionic contrast is used, anaphylactoid reactions can occur, but are rare, and can be avoided by a pretreatment regimen of prednisone, diphenhydramine, and ranitidine.8

1. Moore K.L., Agur A.M.R. Essential Clinical Anatomy. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

2. Lennard T.A. Pain Procedures in Clinical Practice. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus; 2000.

3. O’Kelly E., Garry B. Continuous pain relief for multiple fractured ribs. Br J Anaesth. 1981;53:989-991.

4. Moore D.C., Bridenbaugh L.D. Intercostal nerve block in 4333 patients: Indications, technique, and complications. Anesth Analg. 1962;41:1-11.

5. Moore D.C. Intercostal nerve block for postoperative somatic pain following surgery of thorax and upper abdomen. Br J Anaesth. 1975;47:284-286.

6. Tucker G.T., Moore D.C., Bridenbaugh P.O., et al. Systemic absorption of mepivacaine in commonly used regional block procedures. Anesthesiology. 1972;37:277-287.

7. Hidalgo N.R.A., Ferrante F.M. Complications of paravertebral, intercostal nerve blocks and interpleural analgesia. In: Finucane B.T., editor. Complications of Regional Anesthesia. New York: Springer, 2007.

8. Maddox T.G. Adverse reactions to contrast material: Recognition, prevention, and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(7):1229-1234.