Chapter 22 Information technology and the anaesthetic workstation

Record keeping

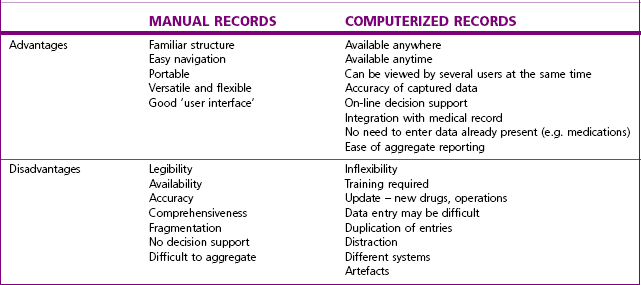

Most anaesthetists in the United Kingdom still create a handwritten record, which is sometimes augmented by a printout from the monitoring systems. These are both only stored in paper format. Table 22.1 lists the advantages and disadvantages of manual records compared with computerized records. The report of the National Confidential Enquiry for Perioperative Deaths for 20001 showed that 5% of case notes were lost, and in 3% of those present the anaesthetic record was missing. There is no evidence that these figures have changed significantly since then. Nevertheless, the report concluded that ‘Improvements in Information Technology can make retrieval of patient information more, rather than less, difficult’. This must be viewed in the context of the time when records were all paper based, and the majority of information systems did not communicate with each other.

Computerized anaesthetic records

Computerized anaesthetic record systems have been available for many years, but despite their benefits and the sophistication of modern systems they have yet to gain widespread acceptance. One of the major impediments to their introduction has been the lack of a ‘business case’ to prove their financial worth. This is despite the fact that anaesthetists are involved in 60% of inpatient hospital activity, and that many studies have shown the benefits of automated records.2,3

One of the difficulties in providing a business case is that there is little, if any, evidence of cash savings from the introduction of a computerized record. However, electronic patient records have been shown to provide many ‘softer’ benefits, including improved patient safety (due to reliable and clear communication), better information about the patient and the clinical process at the point of care, and the ability to identify good and poor care by linking care to outcomes.4

The National Health Service in England is currently making a major investment in information technology for integrated medical records through NHS Connecting for Health.5 Initially anaesthetic and critical care systems were to be a key component, but delays in introducing the core systems have made it unlikely that anaesthetic systems will remain part of the programme. Now it is anticipated that the ‘Clinical Five’6 (see Box 22.1) will be delivered for most hospitals through off-the-shelf solutions, which will be linked to each other and to existing systems (including anaesthesia and critical care) by some form of integration system.

The features required of a computerized anaesthetic system are listed in Box 22.2.

Automatic data capture

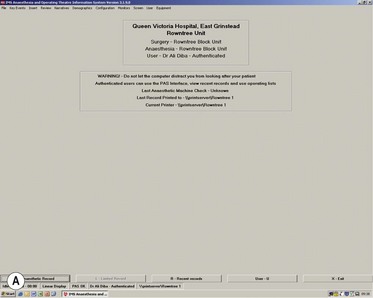

All displayed data from patient and machine monitoring systems (including infusion pumps, ventilators, etc.) should be captured by the system (Fig. 22.1). (Where target controlled infusion pumps are in use, data capture should include details of the pharmacokinetic model used together with the patient variables and the calculated drug concentrations.)

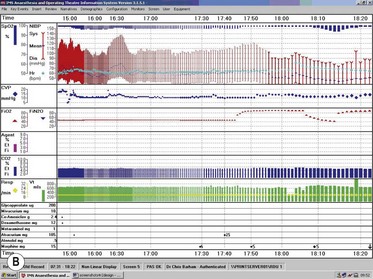

Automatic data logging is perhaps one of the principal benefits of computerised systems for anaesthetists, who may otherwise spend 10–15% of their time during a case on record keeping.7 Some of this time may be saved and, more importantly, transcription errors are avoided. It may be argued that the act of keeping a manual record focuses the attention, but this is unsupported and is outweighed by the provision of a clear detailed graphical record (Fig. 22.2). Any anaesthetist keeping a manual record will be aware of the tendency during long cases for the interval between recordings to increase as the case progresses. An automatic record will maintain recordings with the same granularity throughout – including times when the anaesthetist is occupied directly with the patient.

Data entry

There should be an appropriate method of entering information to the system. This will normally be a keyboard or touch screen, together with some pointing device. These must all be suitable for use in the theatre, and should be easy to clean to avoid cross infection. Washable, sealed, plastic-coated keyboards, which may even be cycled through a dishwasher, are now available (Fig. 22.3).

Data entered should conform to the standards recommended by the Royal College of Anaesthetists (see Box 22.3),8 and the system should be capable of attributing all procedures to the individual member of staff. Data should also adhere to a standard schema and terminology to ensure information is comparable wherever it is collected.9

Box 22.3

Suggested anaesthetic record set

Preoperative information

Assessment and risk factors

(Royal College of Anaesthetists Newsletter 36 (1997) – reproduced with permission.)

Other information and communication systems

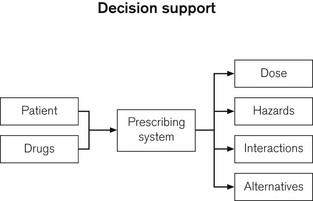

Decision support

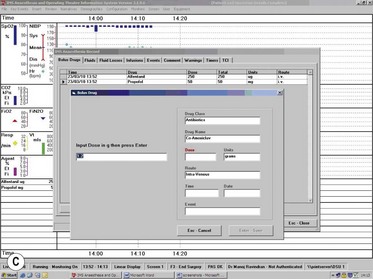

Reference has been made above to the ability of electronic record systems to incorporate decision support. This can be defined as any method that takes input information about a clinical situation and then produces inferences that can assist practitioners in their decision-making. For example a prescribing system (and, hence, also an anaesthetic system) should be able to give the clinician information about dosage, interactions, and alternatives on the basis of embedded knowledge about the patient and drug (Fig. 22.4).

Pharmacology display systems

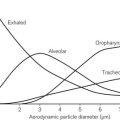

Decision support systems mentioned above should not be merely to warn of rare untoward drug interactions, but can also be made integral to the routine control of anaesthesia. Response surface pharmacodynamic interaction models can be used to guide anaesthetic drug dosing. By automatically acquiring data from infusion pumps, the anaesthesia machine and patient information systems, and by using inbuilt pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic models such ‘advisory display systems’ can be made to predict pharmacodynamic responses and hence used to guide dosing of hypnotic, analgesic, relaxant and ultimately other drugs. Such a system is the SmartPilot View from Dräger (Fig. 22.5).

1 National Confidential Enquiry into Perioperative Deaths. Then and Now. The 2000 Report of the National Confidential Enquiry into Perioperative Deaths. London: NCEPOD; 2000. p. 29

2 Devitt JH, Rapanos T, Kurrek M, Cohen MM, Shaw M. The anaesthetic record: accuracy and completeness. Can J Anaesth. 1999;46:122–128.

3 Byrne AJ, Sellen AJ, Jones JG. Errors in anaesthetic record charts as a measure of anaesthetic perfomance during simulated critical incidents. Br J Anaesth. 1998;80:58–62.

4 http://www.ehr-impact.eu/downloads/documents/EHRI_final_report_2009.pdf..

5 Barham C. IT in the NHS – where are we now? Royal College of Anaesthetists Bulletin. 2010;59:38–40.

6 Department of Health. Health Informatics Review Report. 10 July 2008.

7 Allard J, Dzwonczyk R, Yablok D, Block FE, Jr., McDonald JS. Effect of automatic record keeping on vigilance and record keeping time. Br J Anaesth. 1995;74:619–626.

8 Lack A. New College Guideline for Anaesthetic Records. Newsletter 36. London: Royal College of Anaesthetists; 1997. p. 3

9 Gardner M, Peachey T. A standard XML schema for computerised anaesthetic records. Anaesthesia. 2002;57:1174–1182.