Infections of the Integumentary System, Soft Tissue, and Muscle

After reading this chapter, the student will be able to:

• Classify bacterial skin infection based on the layers of skin and soft tissue involved

• Identify and describe the different kinds of staphylococcal skin infections

• Identify and describe the different kinds of streptococcal skin infections

• Explain the causes of acne and leprosy

• Describe the different kinds of warts and their causative agent

• Discuss skin infections caused by herpesviruses

• Discuss the importance of smallpox

• Describe the different kinds of tineas

Introduction

The skin provides an efficient, significant barrier against invading microbes and thus represents the first line of defense against infection (see Chapter 20, The Immune System). The human skin and mucous membranes host many bacterial species as part of their normal flora (see Chapter 9, Infection and Disease). Although these organisms normally do not cause infections in intact skin, any break in the skin can lead to a range of infections, from treatable to life-threatening skin conditions. There are many types of skin infections caused by different organisms such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. Microbial disease of the skin may result from the following:

• A break in the skin, allowing microorganisms to enter the body

• Systemic infections, which also manifest themselves in the skin (see the Healthcare Application table)

• Toxin-mediated skin damage due to the production of microbial toxins at a site in the body distant from the point of original infection

• Diabetes, because of poor blood flow to the skin

• AIDS, because of a compromised immune system

• Burns, because of a large area of exposed and open skin and underlying tissue areas

• Medical treatments such as chemotherapy, which depress the immune system

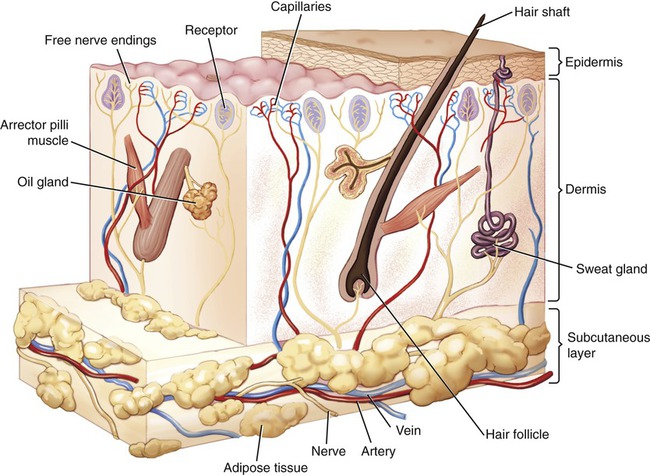

To understand the different types of skin infections and infections of the underlying tissue it is important to understand tissue structure. The skin is composed of three layers: the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue or hypodermis (Figure 10.1).

• The epidermis is composed of five layers of epithelial tissue, where the cells are constantly formed by the innermost layers through mitosis. Within the epidermis are Langerhans cells, which are dendritic cells that play a role in defense against invading microbes (see Chapter 20, The Immune System).

• The dermis consists of two layers: the superficial papillary layer (closest to the epidermis) and a deeper reticular layer. The papillary layer is composed of loose connective tissue and contains blood capillaries that service the epidermis and cutaneous receptors. The reticular layer consists of irregular dense connective tissue surrounding blood vessels, hair follicles, nerves, sweat glands, and sebaceous glands. The epidermis is anchored to the dermis by a basement membrane.

• The hypodermis or subcutaneous layer is made of loose connective tissue with abundant adipose (fat) cells.

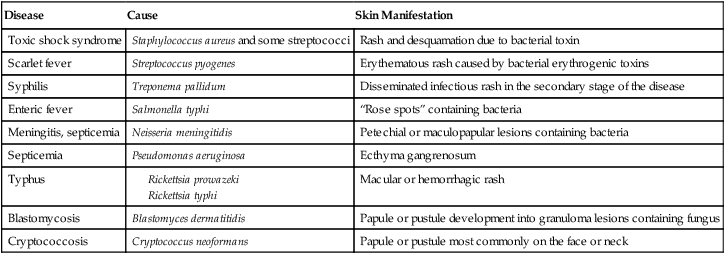

HEALTHCARE APPLICATION

Skin Manifestations of Systemic Bacterial and Fungal Infections

| Disease | Cause | Skin Manifestation |

| Toxic shock syndrome | Staphylococcus aureus and some streptococci | Rash and desquamation due to bacterial toxin |

| Scarlet fever | Streptococcus pyogenes | Erythematous rash caused by bacterial erythrogenic toxins |

| Syphilis | Treponema pallidum | Disseminated infectious rash in the secondary stage of the disease |

| Enteric fever | Salmonella typhi | “Rose spots” containing bacteria |

| Meningitis, septicemia | Neisseria meningitidis | Petechial or maculopapular lesions containing bacteria |

| Septicemia | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Ecthyma gangrenosum |

| Typhus |

Bacterial Infections

• Abscesses: An abscess is a localized collection of pus in an area of tissue that is infected. It is a defensive mechanism of the body to prevent the spread of infectious material to other areas of the body. Abscesses can occur in any kind of solid tissue but most frequently on the skin surface, where they are easily visible. They may be superficial pustules or pimples, furuncles or boils, carbuncles or pyogenic groups of hair follicles, and deep skin abscesses.

• Spreading infections: Can be limited to the epidermis, such as is the case for impetigo, or can involve the subcutaneous fat, as in cellulitis.

• Necrotizing infections: These infections result in the death of the infected tissue (necrosis). Some of these infections spread with alarming rapidity (i.e., “flesh-eating bacteria”) along the surface of the muscles, causing an interruption of blood flow. Because the immune system uses the bloodstream for the purposes of defense, the cells of the immune system and their antibodies cannot reach the infected area; hence the infection can spread rapidly and may be difficult to control. In the case of a necrotic infection, death is not uncommon, even with the appropriate treatment.

Staphylococcal Infections

Furuncles (Boils)

Staphylococcus aureus is the most common cause of boils and persons who are carriers of the virulent strain of Staphylococcus aureus often go through recurrent boils. Exposure to Pseudomonas aeruginosa and/or Pseudomonas folliculitis in hot tubs or swimming pools may also lead to furuncles. The infection begins in a hair follicle (folliculitis) and subsequently spreads into the surrounding dermis (Figure 10.2). Furuncles can occur in the hair follicles anywhere on the body but are most commonly found on the face, neck, armpit, buttocks, and thighs. At first the lesion presents itself as a firm, red, painful nodule and then develops into a large, painful mass that often drains large amounts of pyogenic exudate (pus). Collections of furuncles can fuse to form carbuncles, a large infected mass, which may drain through several sinuses or develop into an abscess. Drainage to the inside can result in access of the bacteria to underlying sites, which can then be the cause of serious infections such as peritonitis, empyema, meningitis, or systemic poisoning (septicemia). Furuncles may heal on their own if they drain properly. Warm moist compresses encourage furuncles to drain and therefore speed up the healing processes. Deep or large lesions most often need to be lanced or drained surgically.

Cellulitis

Cellulitis is an acute infection of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus, streptococci, or other bacteria. The origin of the infection is either a superficial skin lesion such as a boil or ulcers resulting from trauma. Cellulitis is characterized by redness, swelling, warmth, and pain or tenderness and develops within a few hours or days of the trauma. It occurs most commonly on the lower legs (Figure 10.3) and the arms or hands, but other areas of the body may be involved. Regional lymph nodes become enlarged and the patient suffers malaise, chills, and fever. Systemic antibiotics as well as local compresses and analgesics are usually necessary.

Impetigo (Pyoderma)

Impetigo is a superficial skin infection limited to the epidermis, common in infants and children. People who play contact sports (e.g., football, wrestling) are also susceptible, regardless of age. Staphylococcus aureus is an organism that can cause highly contagious infections such as impetigo in neonates, causing a threat in neonatal care units. In older children impetigo may also be caused by group A β-hemolytic streptococci. Scratching, direct contact with hands, eating utensils, or towels can easily be vectors to spread the infection. Lesions start with red or pimple-like sores most commonly on the face, arms, and legs. The small vesicles rapidly enlarge, fill with pus, and subsequently rupture to form yellowish-brown crusty masses (Figure 10.4). Because of autoinoculation with hands, towels, and clothes, additional vesicles develop around the primary site of infection. The treatment of impetigo depends on the age of the child and the severity of the infections and may include hygienic measures, topical treatment, and oral antibiotics in more severe cases.

Streptococcal Infections

Erysipelas

Erysipelas is a type of acute infection generally caused by group A Streptococcus. Historically, the face was the most commonly involved site of infection, but now it accounts for approximately 20% of cases and the legs are most often affected (Figure 10.5). Erysipelas can be distinguished from cellulitis by the raised advancing edges and sharp borders. In general, oral antibiotics such as penicillin (see Chapter 21, Pharmacology, and Chapter 22, Antimicrobial Drugs) are used to treat the infection; however, severe cases, with complications such as bacteremia (bacteria in the blood), might require the use of intravenous antibiotics.

Acute Necrotizing Fasciitis

Necrotizing fasciitis (“flesh-eating bacteria”; see Medical Highlights) is an uncommon infection of the deep layers of the skin and subcutaneous tissue. Although a mixture of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria is often present at the original site of infection, the severe inflammation and tissue necrosis seem to be due primarily to the actions of a highly virulent strain of Streptococcus pyogenes (gram-positive, group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus), the organism responsible for “strep throat.” These infections typically originate in the mucous membranes (e.g., the throat) or skin. Necrotizing fasciitis is a progressive, rapidly spreading, inflammatory infection causing secondary necrosis of subcutaneous tissue and adjacent fascia. Proteases, which are tissue-destroying enzymes released by the pathogen, are the cause of the necrosis. The infected area becomes noticeably inflamed, painful, and enlarged, and symptoms of dermal gangrene are apparent. Systemic toxicity accompanied by fever, tachycardia, hypotension, mental confusion, disorientation, and possibly organ failure occur. Immediate and aggressive treatment is essential, including surgical removal of all infected tissue, accompanied by aggressive antimicrobial therapy, fluid replacement, and possible amputation to prevent further spread of the infection. The mortality rate is estimated to be 40% to 60%.

Acne

Acne is caused by Propionibacterium acnes, a bacterium present on the skin of most people. It lives on fatty acids secreted by sebaceous glands, which in adolescence have increased activity due to hormonal changes (Figure 10.6). This excessive amount of sebum released results in the formation of whiteheads and blackheads, and the breakdown of sebum by P. acnes causes local inflammation and the eruption of pimples, sometimes causing skin lesions (folliculitis) that can result in permanent scar formation. P. acnes can be treated with antibiotics and antibacterial preparations; however, tetracycline-resistant P. acnes is becoming common.

Leprosy

Leprosy (Hansen’s disease) is caused by Mycobacterium leprae and previously affected millions of people worldwide. Although leprosy still represents a health problem in parts of Africa, Asia, the South Pacific, and some South American countries, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) the global number of new cases detected annually has decreased dramatically, and continues to do so. Leprosy is not highly contagious and prolonged exposure to a source is necessary for infection. Transmission of the infection is related to overcrowding and poor hygiene; it generally occurs by direct contact and aerosol inhalation. The clinical manifestations vary but generally affect the skin, mucous membranes, and nerves (see Chapter 13, Infections of the Nervous System and Senses). The chronic disease is classified as borderline, paucibacillary, or multibacillary leprosy.

• Borderline leprosy is the most common form; the skin lesions, or macules, resemble those of tuberculoid leprosy (i.e., hypopigmented areas without feeling, due to destruction of nerve tissue by the immune response) but are more numerous and irregular.”

• Paucibacillary leprosy is characterized by one or more hypopigmented skin macules and damaged peripheral nerves, resulting from attack by inflammatory cells of the immune response.

• Multibacillary leprosy is associated with symmetric skin lesions, nodules, thickened dermis, and damage to the nasal mucosa (Figure 10.7).Typically there is no loss of feeling because patients with this form of leprosy do not mount an effective immune response.

The mechanism of pathogenicity is relatively unknown because the organism cannot be grown on artificial culture medium, making it difficult to study in the laboratory environment. Laboratory diagnosis of M. leprae therefore depends on microscopic examination of skin biopsies. Treatment of leprosy includes antibiotics, rehabilitation, and education. In the case of immunocompromised patients drug treatment might be required over the entire lifetime. An overview of bacterial skin infections is given in Table 10.1.

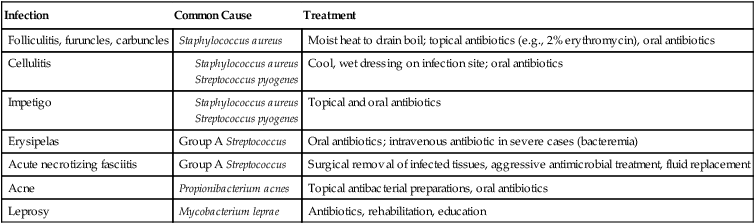

TABLE 10.1

Bacterial Infections of the Skin

| Infection | Common Cause | Treatment |

| Folliculitis, furuncles, carbuncles | Staphylococcus aureus | Moist heat to drain boil; topical antibiotics (e.g., 2% erythromycin), oral antibiotics |

| Cellulitis |

Viral Infections

Viruses are the most common causes of acute infections that do not necessarily require hospitalizations. This section deals with viral infections that involve the integument, but also can engage other systems as well. Some viruses can enter through a break in the skin; some can be introduced through an insect bite. Only a few viruses gain access to the human body via an animal bite, hypodermic needles, blood transfusion, or acupuncture. A summary of viral skin infections is provided in Table 10.2. Some viruses enter through the respiratory system and cause skin lesions. These include the viruses causing measles, rubella, and chickenpox (see Chapter 11, Infections of the Respiratory System).

TABLE 10.2

Common Viral Infections of the Skin

| Infection | Common Cause | Treatment |

| Warts | Human papillomavirus | Application of salicylic and lactic acid; freezing with liquid nitrogen; electrodesiccation; immunotherapy; laser surgery |

| Cold sores | HSV-1 or HSV-2 (less common) | Antiviral topical ointments, antiviral oral medications |

| Chickenpox | Varicella-zoster virus | No medical treatment (generally); antihistamine to relieve itching; antiviral in high-risk cases |

| Shingles | Varicella-zoster virus | Bed rest; topical agents; cool compresses to affected skin areas; antiviral medications; steroids; antidepressants and anticonvulsants if needed |

| Roseola infantum | HHV-6 and HHV-7 | Treatment for fever |

| Molluscum contagiosum | Molluscum contagiosum | No treatment necessary in people with a functioning immune system |

| Smallpox | Variola virus | Vaccination |

• Measles: Measles is caused by a paramyxovirus of the genus Morbillivirus. Measles is an acute, highly communicable respiratory disease that also manifests itself as a characteristic skin rash. It is a generalized, maculopapular, erythematous rash that begins after the fever starts (see Chapter 11). In general, the area where the rash starts is the head, followed by spreading to cover most of the body and often causing extreme itching.

• Rubella: Also called German measles, rubella is caused by the rubella virus of the family Togaviridae. This is also a respiratory infection (see Chapter 11) with additional manifestation in the skin, in the form of a rash that appears on the face and then spreads to the trunk and limbs. The rash appears as pink dots under the skin on the first or third day of the illness and then disappears after a few days without peeling of the skin. The condition is generally fairly benign but is a major concern in pregnant women because the disease can cause congenital rubella, a serious condition for the fetus (see Congenital Rubella in Chapter 23, Human Age and Microorganisms).

• Chickenpox and shingles: These are discussed in the section Varicella-Zoster Infections, later in this chapter.

Warts

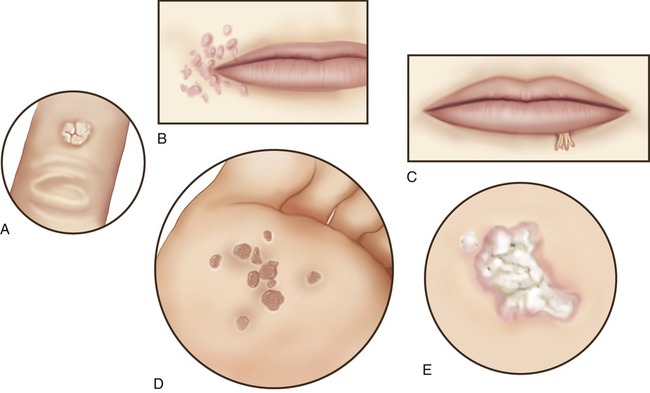

The virus is transmitted by direct contact with an individual or by fomites such as a towel. Autoinoculation is sometimes responsible for the spreading of warts in an individual. Different types have been identified according to shape (Figure 10.8), site affected, and type of HPV:

A, Common wart; B, flat wart; C, filiform wart; D, plantar wart; E, mosaic wart.

• Common wart: Raised with roughened surface; grayish-yellow or brown in color, mostly on hands, around nails, and knees

• Flat wart: Small, smooth, flattened, tan or flesh colored; may occur in large numbers, commonly on the face, neck, hands, wrists, and knees

• Filiform or digitate wart: Fingerlike (threadlike) wart; common on the face, near eyelids and lips

• Plantar wart: Hard lump, occasionally painful; often shows multiple black specks in the center; found at pressure points on soles of the feet

• Mosaic wart: A group of tightly clustered plantar-type warts, found on hands or soles of the feet

• Genital wart: Often occur in clusters, can be tiny or can spread into large masses in the genital area; warts on the genitals are contagious and the virus is transmitted to another person during oral, vaginal, or anal sex (see Chapter 17, Sexually Transmitted Infections/Diseases)

Herpes Simplex Infections

Herpes infections generally manifest themselves as painful, watery blisters in the skin or mucous membranes of the lips, mouth, or the genitals (Figure 10.9). The herpes simplex virus has two strains: herpes simplex virus 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and HSV-2). HSV-1 usually causes infections on the lips and in the mouth (fever blisters), whereas HSV-2 is primarily responsible for genital herpes. It should be noted that both strains can potentially infect both general regions. All herpesviruses have the capacity to remain latent in the ganglia of the sensory fibers innervating a particular area of the skin. Subsequent infections therefore have the tendency to appear in the same areas. HSV is transmitted by direct contact of lips or genitals during the time when the sores are present or just before they appear. The mechanism(s) of reactivation of the virus are poorly understood but several factors have been identified to cause reoccurrence: ultraviolet light, x-rays, heat, cold, hormonal imbalance, and emotional or other stress factors. Herpes can also be transmitted during childbirth and the disease can be fatal to the infant. Both viruses can also cause morbidity and mortality in an immunosuppressed person.

Varicella-Zoster Infections

The primary disease caused by VZV is chickenpox, which is usually relatively mild in children but more severe if it affects adults. Because the virus is latent, it can be reactivated in older adults or in people with impaired immunity. Once reactivated, the virus replicates along the neural pathways and infects the skin, causing a characteristic rash along the entire dermatome (Figure 10.10).

Smallpox

Smallpox is an acute contagious disease caused by the variola virus, a member of the orthopoxvirus family. It is one of the most devastating diseases known to humans and for centuries epidemics swept across continents, drastically reducing the population. The virus can be spread from person to person by contact with skin lesions or via secretions of the respiratory tract. The disease, for which no effective treatment has been developed, kills approximately 30% of the infected population. Survivors show characteristic deep pitted scars (pockmarks), which are most prominent on the face. The incubation period is usually 12 to 14 days and is followed by the sudden onset of influenza-like symptoms such as fever, malaise, headache, prostration, and severe back pain; when the digestive system becomes involved, abdominal pain and vomiting occur. A few days later, when the body temperature falls, the characteristic pimples associated with the disease start to erupt in the mouth, arms, and hands and later on the rest of the body (Figure 10.11). These pimples, now called macules, are still small but the patient is at the most contagious stage.

In 1967 the WHO started a campaign to eradicate smallpox by vaccination (originally developed by Edward Jenner) with a live attenuated strain of the vaccinia virus. After successful vaccination campaigns throughout the world, the WHO certified the eradication of smallpox in 1979. Cultures of the virus are kept by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States and at the Russian Vector Institute for Virology in Novosibirsk, Siberia. Concern about the use of smallpox by bioterrorists resulted in the preparation of contingency plans by many countries to deal with potential threats (see Chapter 24, Microorganisms in the Environment and Environmental Safety). These plans include the stockpiling of the smallpox vaccine. In December 1999, the WHO Advisory Committee on Variola Virus Research concluded that the then current vaccine supplies to prevent and control a smallpox outbreak were limited. As a result, a number of governments have chosen to examine their stocks, test their potency, and consider whether more vaccine is required. At present, the United States has a big enough stockpile of the smallpox vaccine to vaccinate everyone in the United States in the event of a smallpox emergency (CDC information).

Fungal Infections (Mycoses)

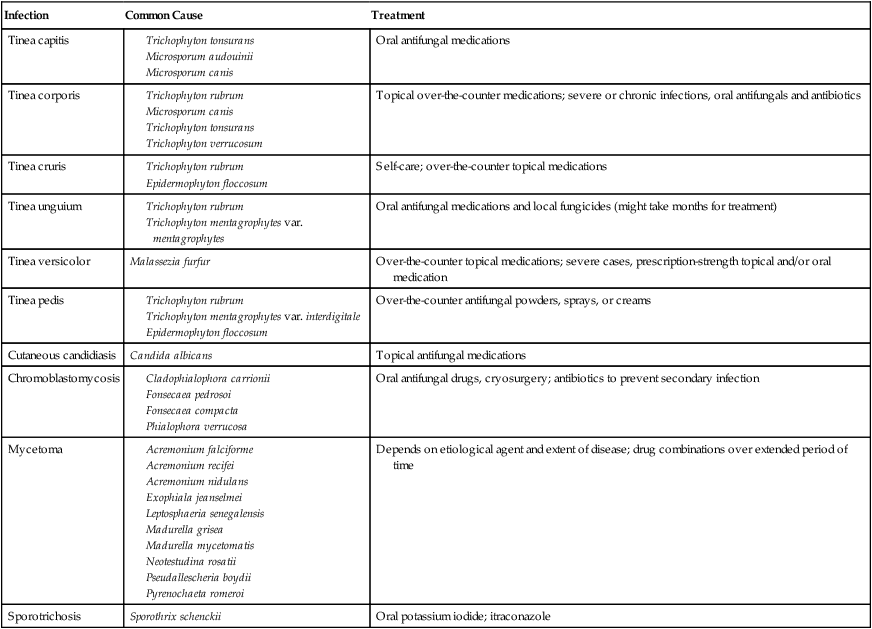

Fungal infections of the skin are referred to as mycoses, and they are common and usually mild. However, in people with a compromised immune system, fungi can cause potentially serious diseases. Fungi are parasites or saprophytes; they exist off living or dead organic matter (see Chapter 8, Eukaryotic Microorganisms). Some fungi infect humans only; others can cause disease in other animals as well. Although the natural fungal habitat is the soil, they are often transmitted by direct contact with an infected person, an animal, or indirectly through contact with a fomite (e.g., a towel, or the floor). Many fungi live on damp surfaces such as the floors in public showers and locker rooms, where they can be readily picked up by direct contact. Fungi also prefer moist areas of the human body such as skin folds, between the toes, and genital areas. A summary of common fungal infections is illustrated in Table 10.3.

Tineas

Tineas refer to fungal infections superficially affecting the outer layers of the skin, the nails, and the hair. The causative agents live off the dead, keratinized cells of the epidermis. The most important fungi that cause disease of skin, hair, and nails are called dermatophytes. Tinea is a common skin inhabitant and may cause several types of superficial skin infections, named depending on the area of the body infected. As the fungus grows it spreads out in a circle, leaving normal-looking skin in the middle. This ringlike formation is why this type of infection is called “ringworm” (Figure 10.12), but contrary to its name it is not caused by a worm, but by fungi causing tinea.

Tinea Pedis

Tinea pedis, commonly called “athlete’s foot,” thrives in warm and humid conditions. The infection is most frequently due to Trichophyton rubrum, T. interdigitale, and Epidermophyton floccosum. Of all the tinea infections, athlete’s foot is the most common. It generally causes cracked, flaking, peeling skin between the toes and the affected areas are commonly red. Itchiness, burning, or stinging and blisters, oozing, or crusting may occur as well (Figure 10.13). The infection may also spread to the heels, palms, and between the fingers. Athlete’s foot is contagious and can be obtained through direct contact or fomites such as shoes, stockings, showers, or pool surfaces (see Life Application: Athlete’s Foot). The afflicted feet may have a foul odor and secondary bacterial infections are not uncommon, which adds to the inflammation and possible necrosis. Over-the-counter antifungal powders, sprays, or creams can help to control the infection.

Summary

• The skin is the first line of defense against infection and any break in the skin may result in invasion by pathogens or opportunistic organisms. A wide range of organisms is associated with skin infections and disease.

• Microbial disease of the skin may occur as a result of a break in the intact skin, systemic infections manifesting themselves in the skin, or toxin-mediated skin damage due to microbial toxins at different areas of the body.

• Bacterial skin infections are classified on an anatomical basis, depending on the layers of skin and soft tissues involved, as abscesses, spreading infections, or necrotizing infections.

• Bacterial skin infections include staphylococcal infections such as furuncles, carbuncles, cellulitis, and impetigo; streptococcal infections; acute necrotizing fasciitis; acne; and leprosy.

• Some viruses can enter through a break in the skin or via an insect bite and some viruses have a different port of entry and manifest themselves in skin lesions. Skin infections include warts, herpes simplex infections, varicella-zoster infections, molluscum contagiosum, roseola infantum, and smallpox.

• Measles, rubella, and chickenpox are respiratory diseases, but also show skin lesions.

• Most fungal infections are superficial, involving the outer layers of the skin, the nails, and hair. These infections include tineas and cutaneous candidiasis.

• Subcutaneous mycoses occur when pathogens penetrate the dermis and deeper layers. The three general types are chromoblastomycoses, mycetomas, and sporotrichosis.

Review Questions

1. Langerhans cells, which play a role in defense against microbes, are located in the:

2. The papillary layer of the skin is part of the:

3. Which of the following organisms is the causative agent for skin infections and toxic shock syndrome?

4. Which of the following is a type of acute infection generally caused by group A Streptococcus?

5. The organism often called “flesh-eating bacteria” is:

7. Warts are commonly caused by:

8. Herpes simplex infections on lips and in the mouth are most commonly caused by:

9. “Athlete’s foot” is caused by:

10. Diaper rash in infants is commonly caused by:

11. Leprosy is caused by __________.

12. Infections that result in the death of infected tissue are called __________ infections.

13. Chickenpox and shingles are caused by the __________ virus.

14. Fungal infections of the skin are referred to as __________.

15. A tinea infection in the groin area is commonly called “__________.”

16. Describe the different types of warts according to shape and site affected.

17. Describe the most common staphylococcal skin infections.

18. Describe the most common streptococcal skin infections.

19. Discuss the occurrence of smallpox and smallpox vaccination.