Infections of the Circulatory System

After reading this chapter, the student will be able to:

• Identify the causes and symptoms of endocarditis, myocarditis, and pericarditis

• Describe blood-borne infectious diseases and microbemia

• Differentiate between bacteremia and septicemia

• Describe the transmission, symptoms, and treatment of rheumatic fever and gangrene

• Discuss zoonotic bacterial infections

• Describe the vector-transmitted bacterial diseases affecting the circulatory system

• Describe the cause, transmission, symptoms, and treatment for infectious mononucleosis

• Describe the causes and symptoms of viral hemorrhagic fevers

• Discuss the causes, symptoms, and treatment of systemic mycoses

• Describe the origin and transmission of the different protozoan infections that affect the circulatory system

Introduction

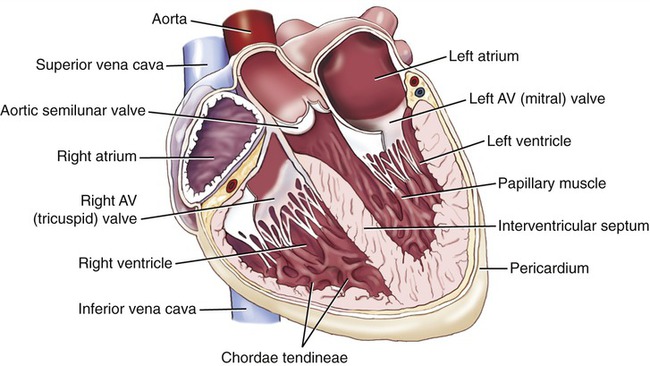

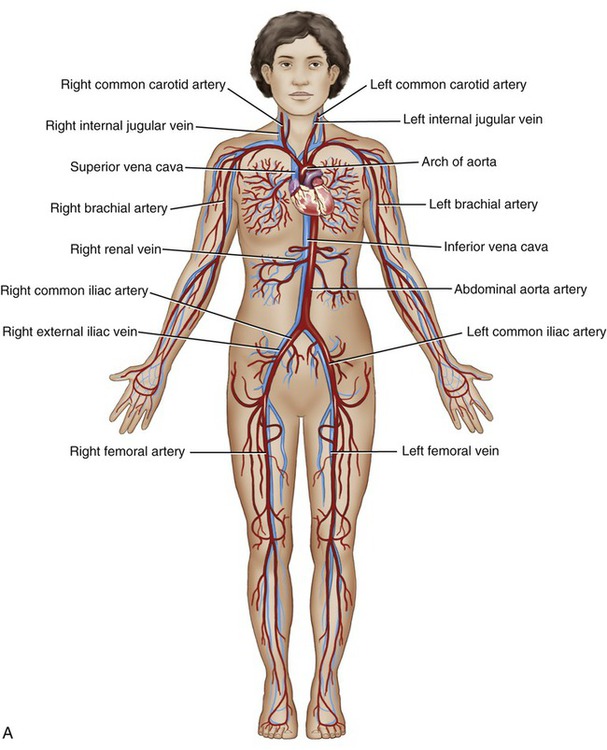

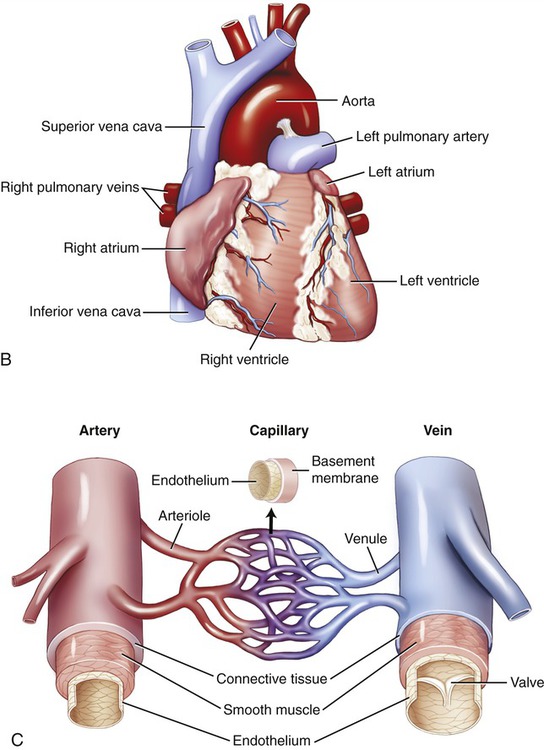

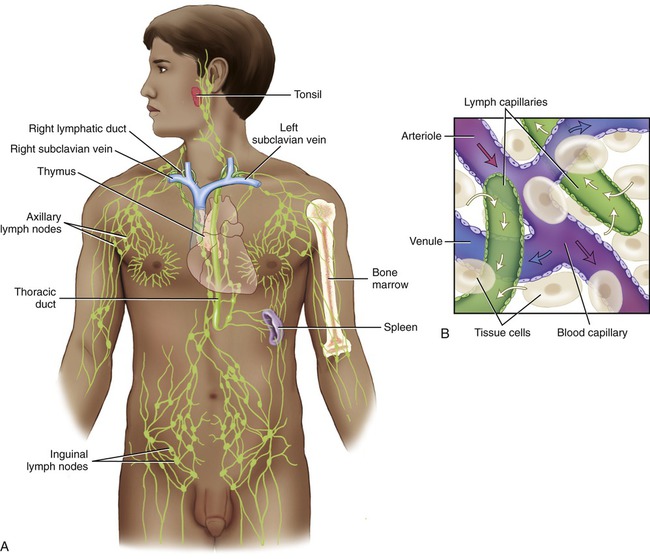

The circulatory system includes the cardiovascular system and the lymphatic system. The lymphatic system consists of the lymph, lymphatic vessels, lymphatic tissue, and lymphatic organs, and is discussed in Chapter 20 (The Immune System). The cardiovascular system consists of the heart, blood, and blood vessels (Figure 14.1). Infection and inflammation of the cardiovascular system frequently cause cardiac and vascular disease. The lymphatic system returns excess tissue fluid back to the cardiovascular system and therefore has direct access to the cardiovascular system. The relationship between the cardiovascular and lymphatic systems is illustrated in Figure 14.2. Once microorganisms gain access to either one of the systems they can spread throughout the body and therefore have the potential to infect any organ system. In general, bacterial and fungal infections will affect the endocardium (tissue lining of the heart chambers), causing endocarditis, whereas viral and parasitic infections affect the myocardium (heart muscle), resulting in myocarditis. Inflammation and infection of the pericardium (membrane surrounding the heart), called pericarditis, can be caused by bacteria, viruses, and rarely by fungi.

A, The cardiovascular system consists of the heart (B) and the blood and blood vessels (C).

A, The lymphatic vessels drain excess fluid from the tissues and return it to the cardiovascular system. B, The inset shows the relationship between the blind-ended lymphatic capillaries and the blood capillaries.

Endocarditis

Endocarditis is an inflammation of the endocardium, the lining of the heart or the heart valves (Figure 14.3). The condition can be classified as infective if a microorganism is involved, or as noninfective. Noninfective endocarditis involves the formation of platelet and fibrin thrombi on heart valves and the surrounding endocardium, in response to trauma, circulating immune complexes, vasculitis, or a hypercoagulated state. Infective endocarditis symptoms may develop slowly (subacute) or suddenly and they include the following:

Pericarditis

Pericarditis is the term used to describe inflammation of the pericardium, the saclike membrane surrounding the heart (see Figure 14.3). The condition is usually a result of complications of a viral infection, but can also be caused by bacteria and fungi. The symptoms include the following:

Blood-borne Infectious Diseases

Blood-borne disease is spread by contaminated blood or bodily fluids. Any exposure to blood or other bodily fluids can transmit infectious disease. Although blood-borne diseases can affect anyone exposed to infected blood or bodily fluids, the risk of exposure is greater with certain occupations such as healthcare, emergency response, public safety, teaching, and many others (see Chapter 5, Safety Issues). Pathogens of primary concern for these professions, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, Atlanta, GA), are HIV, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and those causing viral hemorrhagic fever. These viruses are discussed in detail in Chapter 17 (Sexually Transmitted Infections/Diseases). Diseases that are not transmitted directly by blood or by contact with bodily fluids, but by an insect or other vector, are classified as vector-borne diseases.

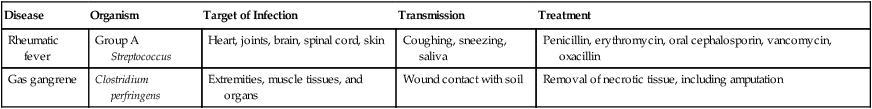

Bacterial Infections

Once bacteria have access to the circulatory system they become widely dispersed (bacteremia) and are capable of infecting a wide range of tissues and organs. If the bacteria in the circulatory system are not destroyed by the immune system or by antibiotic treatment, they can multiply in the blood and cause septicemia. Examples of bacterial diseases of the circulatory system are illustrated in Table 14.1.

TABLE 14.1

Bacterial Diseases of the Circulatory System

| Disease | Organism | Target of Infection | Transmission | Treatment |

| Rheumatic fever | Group A Streptococcus | Heart, joints, brain, spinal cord, skin | Coughing, sneezing, saliva | Penicillin, erythromycin, oral cephalosporin, vancomycin, oxacillin |

| Gas gangrene | Clostridium perfringens | Extremities, muscle tissues, and organs | Wound contact with soil | Removal of necrotic tissue, including amputation |

Bacteremia

Blood is normally sterile, but microorganisms can enter the blood under a variety of conditions. Bacteremia is the term used when bacteria are present in the bloodstream (see Chapter 9, Infection and Disease). Bacteremia has various possible causes including infection during dental procedures, catheterization and the placement of other indwelling devices, surgical procedures, wound infection, and many more. In general, the presence of bacteria in the blood elicits a strong immune response by circulating macrophages, the complement system, and lymphocytes (see Chapter 20, The Immune System), thus preventing bacteria from multiplying. In addition, the blood is relatively low on iron, a requirement for most bacterial growth. If the defenses of the immune and circulatory systems fail microbes can undergo uncontrolled proliferation in the blood, causing a condition called septicemia.

Septicemia

Sepsis is a toxic condition caused by the spread of bacteria or bacterial toxins from the site of infection (see Chapter 9, Infection and Disease). Septicemia is sepsis that occurs when bacteria multiply in the bloodstream. Septicemia is a medical emergency that requires immediate medical treatment. If the condition progresses to septic shock the death rate is as high as 50%, depending on the type of organism involved. Septic shock is the result of hypotension (low blood pressure) despite adequate fluid substitution. Septicemia develops quickly and the patient becomes extremely ill. Although each individual may experience symptoms differently the most common symptoms include the following:

Rheumatic Fever

Rheumatic fever is an inflammatory disease that can develop as a rare complication after a group A streptococcal infection such as strep throat or scarlet fever (see Chapter 11, Medical Highlights: Complications of “Strep Throat”). The condition commonly involves the heart, joints, brain, spinal cord, and skin. In general, rheumatic fever occurs in children between the ages of 4 and 18 years. Symptoms normally begin several weeks after the disappearance of localized throat symptoms and vary greatly between individuals, depending on the parts of the body inflamed. The most common symptoms include the following:

Gangrene

Gangrene is a complication of necrosis, the decay and death of tissue, that is often related to wounds. If the blood supply to a tissue is interrupted by an infection or ischemia (restriction of blood supply) gangrene can occur. Gangrene most commonly affects the extremities (Figure 14.4); however, it can also occur in muscle tissue and organs. Enzymes released from the dying cells and tissue will further destroy the surrounding tissues and thus provide a perfect nutrient environment for many bacterial species. Tissues devoid of blood supply become ischemic and provide an environment for anaerobic bacteria. Several species of the genus Clostridium, gram-positive, endospore-forming anaerobes, grow easily under these conditions. Clostridium is commonly found in soil as well as in the intestinal tracts of humans and domestic animals. The most frequent species involved in gangrene is C. perfringens, but other species and several other genera of bacteria can also grow under the conditions mentioned.

There are different types of gangrene, including the following:

• Dry gangrene, due to ischemia and generally beginning at the distal portions of a limb such as in the feet. This condition often occurs in elderly patients with arteriosclerosis, and other persons with impaired peripheral blood flow, such as diabetic patients.

• Internal gangrene, also called white gangrene, is noticeable by the bleaching of internal tissue, and is generally contracted after surgery or trauma.

• Wet gangrene occurs in organs lined by mucous membranes such as the mouth, lower intestinal tract, lungs, and cervix. Although not necessarily associated with moist tissue, bedsores are also categorized as wet gangrene infections. Toxic products formed by the infecting bacteria can be absorbed if the affected tissue is not removed, resulting in septicemia or toxemia, and eventually death.

• Gas gangrene is caused by bacteria that produce gas within the infected tissue. Toxins produced by the bacteria will cause necrosis of more tissue, thereby providing further bacterial growth. If untreated, the condition is fatal.

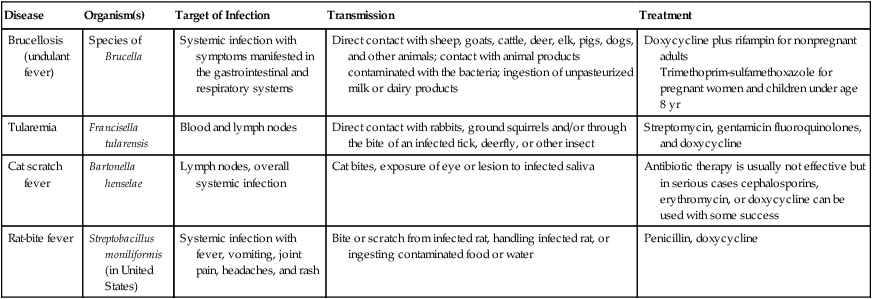

Zoonotic Diseases

Any disease and/or infection that can be transmitted from vertebrate animals to humans is classified as a zoonosis. More than 200 zoonoses have been described, but not all affect the circulatory system (Table 14.2). Zoonoses may be caused by bacteria, viruses, parasites, and unconventional agents such as prions. The emerging field of conservation medicine integrates human medicine, veterinary medicine, and environmental services and is largely concerned with zoonoses.

TABLE 14.2

Zoonotic Infections of the Circulatory System

| Disease | Organism(s) | Target of Infection | Transmission | Treatment |

| Brucellosis (undulant fever) | Species of Brucella | Systemic infection with symptoms manifested in the gastrointestinal and respiratory systems | Direct contact with sheep, goats, cattle, deer, elk, pigs, dogs, and other animals; contact with animal products contaminated with the bacteria; ingestion of unpasteurized milk or dairy products | Doxycycline plus rifampin for nonpregnant adults Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for pregnant women and children under age 8 yr |

| Tularemia | Francisella tularensis | Blood and lymph nodes | Direct contact with rabbits, ground squirrels and/or through the bite of an infected tick, deerfly, or other insect | Streptomycin, gentamicin fluoroquinolones, and doxycycline |

| Cat scratch fever | Bartonella henselae | Lymph nodes, overall systemic infection | Cat bites, exposure of eye or lesion to infected saliva | Antibiotic therapy is usually not effective but in serious cases cephalosporins, erythromycin, or doxycycline can be used with some success |

| Rat-bite fever | Streptobacillus moniliformis (in United States) | Systemic infection with fever, vomiting, joint pain, headaches, and rash | Bite or scratch from infected rat, handling infected rat, or ingesting contaminated food or water | Penicillin, doxycycline |

Vector-transmitted Diseases

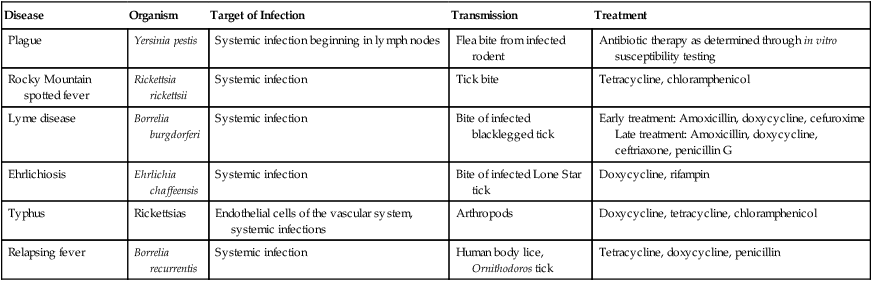

Vectors are animals that are capable of transmitting infectious diseases. These vectors include, but are not limited to, flies, mites, fleas, ticks, and rats. Insects are a major cause of human mortality and morbidity due to the transmission of infectious pathogens by blood-feeding species. The transmission of vector-borne diseases is based on a complex relationship between a parasite, the vector, and humans. Vectors are mobile and add an additional dimension to the range of transmission of infectious diseases. This particular section addresses bacterial vector-borne diseases (Table 14.3).

TABLE 14.3

Vector-transmitted Diseases of the Circulatory System

| Disease | Organism | Target of Infection | Transmission | Treatment |

| Plague | Yersinia pestis | Systemic infection beginning in lymph nodes | Flea bite from infected rodent | Antibiotic therapy as determined through in vitro susceptibility testing |

| Rocky Mountain spotted fever | Rickettsia rickettsii | Systemic infection | Tick bite | Tetracycline, chloramphenicol |

| Lyme disease | Borrelia burgdorferi | Systemic infection | Bite of infected blacklegged tick | Early treatment: Amoxicillin, doxycycline, cefuroxime Late treatment: Amoxicillin, doxycycline, ceftriaxone, penicillin G |

| Ehrlichiosis | Ehrlichia chaffeensis | Systemic infection | Bite of infected Lone Star tick | Doxycycline, rifampin |

| Typhus | Rickettsias | Endothelial cells of the vascular system, systemic infections | Arthropods | Doxycycline, tetracycline, chloramphenicol |

| Relapsing fever | Borrelia recurrentis | Systemic infection | Human body lice, Ornithodoros tick | Tetracycline, doxycycline, penicillin |

Plague

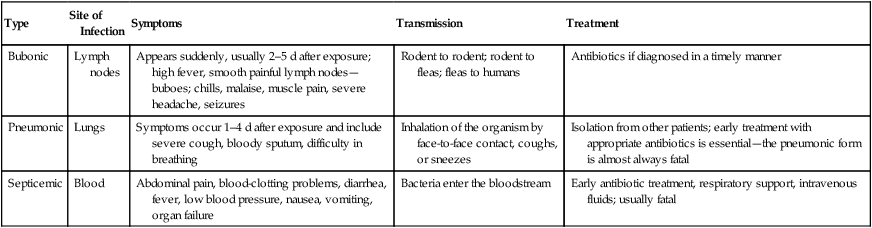

The plague is an infectious disease caused by Yersinia pestis, a gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium. People usually become infected when bitten by a flea that carries the bacteria from an infected rodent or by handling an infected animal. After the flea bite, the bacteria enter the bloodstream and proliferate in the lymph and blood. Y. pestis can reproduce within cells; therefore even if phagocytosed, they still survive. Once the organism enters the lymph it causes swelling of the lymph nodes, especially in the groin and armpits. These swellings are referred to as buboes, and the term buboes led to the disease’s name, bubonic plague (Figure 14.5). Because the lymph is delivered to the subclavian veins via the right lymphatic duct and the thoracic duct, it ultimately enters the bloodstream and the bacteria within the lymph are now capable of multiplying in the blood, causing septicemic plague, which is followed by septic shock. Septicemic plague can occur when the bacteria enter the bloodstream directly through a flea bite, or as a complication of the bubonic or pneumonic plague. All forms of the plague can be treated with antibiotics in the early stages, but if untreated, septicemic plague is universally fatal.

HEALTHCARE APPLICATION

Types of the Plague

| Type | Site of Infection | Symptoms | Transmission | Treatment |

| Bubonic | Lymph nodes | Appears suddenly, usually 2–5 d after exposure; high fever, smooth painful lymph nodes—buboes; chills, malaise, muscle pain, severe headache, seizures |

Rodent to rodent; rodent to fleas; fleas to humans | Antibiotics if diagnosed in a timely manner |

| Pneumonic | Lungs | Symptoms occur 1–4 d after exposure and include severe cough, bloody sputum, difficulty in breathing | Inhalation of the organism by face-to-face contact, coughs, or sneezes | Isolation from other patients; early treatment with appropriate antibiotics is essential—the pneumonic form is almost always fatal |

| Septicemic | Blood | Abdominal pain, blood-clotting problems, diarrhea, fever, low blood pressure, nausea, vomiting, organ failure | Bacteria enter the bloodstream | Early antibiotic treatment, respiratory support, intravenous fluids; usually fatal |

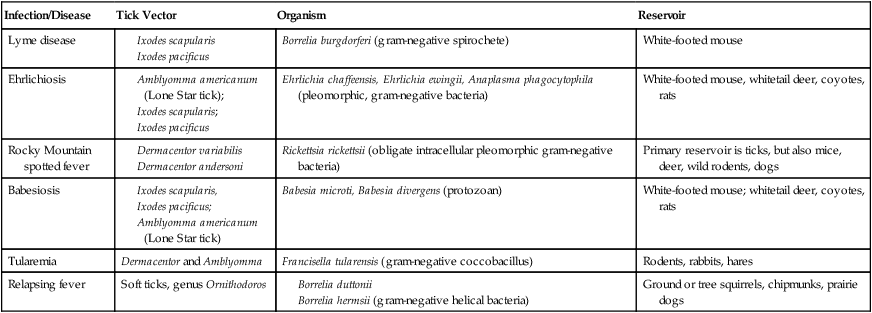

Lyme Disease

Lyme disease is caused by Borrelia burgdorferi, a gram-negative, motile spirochete that is transmitted to humans by the bite of an infected blacklegged tick (Figure 14.7). The infection in humans presents itself in three stages. Typical early symptoms include the following:

Relapsing Fever

1. Louse-borne relapsing fever is transmitted by the human body louse and causes the epidemic form of the disease.

2. Tick-borne relapsing fever is transmitted by the Ornithodoros tick and represents the endemic form of the disease.

HEALTHCARE APPLICATION

Examples of Tick-related Infections

| Infection/Disease | Tick Vector | Organism | Reservoir |

| Lyme disease |

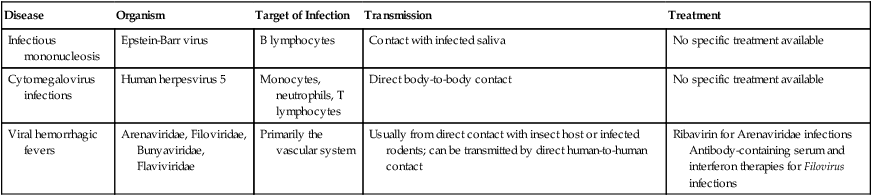

Viral Infections

Viruses can cause a number of cardiovascular and lymphatic system diseases, and with a few exceptions most of them are prevalent in tropical areas (Table 14.4).

TABLE 14.4

Viral Diseases of the Circulatory System

| Disease | Organism | Target of Infection | Transmission | Treatment |

| Infectious mononucleosis | Epstein-Barr virus | B lymphocytes | Contact with infected saliva | No specific treatment available |

| Cytomegalovirus infections | Human herpesvirus 5 | Monocytes, neutrophils, T lymphocytes | Direct body-to-body contact | No specific treatment available |

| Viral hemorrhagic fevers | Arenaviridae, Filoviridae, Bunyaviridae, Flaviviridae | Primarily the vascular system | Usually from direct contact with insect host or infected rodents; can be transmitted by direct human-to-human contact | Ribavirin for Arenaviridae infections Antibody-containing serum and interferon therapies for Filovirus infections |

Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers

• They are RNA viruses, covered or enveloped.

• They need a natural reservoir such as an insect host or other animal.

• They are geographically restricted, depending on the host species.

• Humans are not the natural reservoir; however, by accidental contact the viruses can be transmitted from human to human.

• Human cases during outbreaks caused by these viruses are sporadic and cannot be easily predicted.

• With a few exceptions, there is no cure or treatment for VHFs.

All types of VHFs are characterized by:

• Overall vascular system damage

• Bleeding disorders, all of which can progress to extremely high fever, shock, and death

An infected person may transmit the disease to other persons either by person-to-person contact, through bodily fluids, or by contact with contaminated objects, contaminated syringes, and needles. Infected people who travel to other areas of the country or world can then infect people outside of the original geographical area (also see Chapter 18, Emerging Infectious Diseases).

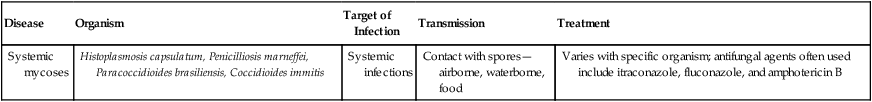

Fungal Infections

Under the right circumstances fungi can enter the human body via the lungs, through the gastrointestinal system, the paranasal sinuses, or the skin. The fungi then spread via the bloodstream or the lymphatic system to the rest of the body (Table 14.5). Most of the mycoses are discussed in the fungal infection sections of the individual body systems. For details about mycoses, see Fungal Infections in Chapters 1–17.

TABLE 14.5

Fungal Diseases of the Circulatory System

| Disease | Organism | Target of Infection | Transmission | Treatment |

| Systemic mycoses | Histoplasmosis capsulatum, Penicilliosis marneffei, Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, Coccidioides immitis | Systemic infections | Contact with spores—airborne, waterborne, food | Varies with specific organism; antifungal agents often used include itraconazole, fluconazole, and amphotericin B |

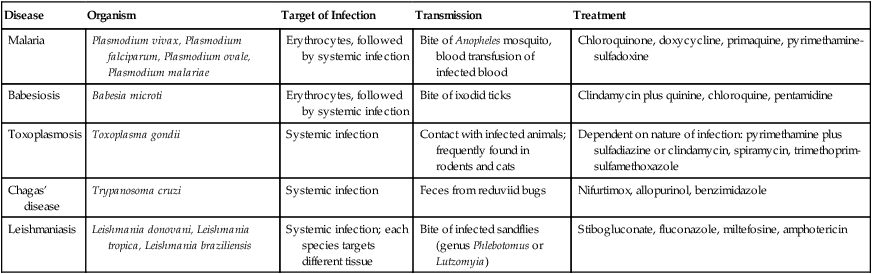

Protozoan Infections

Protozoa causing diseases of the circulatory system generally have complex life cycles (see Chapter 8, Eukaryotic Microorganisms) and present unique challenges for treatment and control. The life cycles of many protozoa include intermediate hosts, which may allow for control by interruption of the infection by elimination of the transmission vectors. Once a protozoan infection has reached the human circulatory system, treatment becomes problematic because many of the drug therapies that target these eukaryotic organisms can also be toxic to human cells (Table 14.6).

TABLE 14.6

Protozoan Diseases of the Circulatory System

| Disease | Organism | Target of Infection | Transmission | Treatment |

| Malaria | Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium ovale, Plasmodium malariae | Erythrocytes, followed by systemic infection | Bite of Anopheles mosquito, blood transfusion of infected blood | Chloroquinone, doxycycline, primaquine, pyrimethamine-sulfadoxine |

| Babesiosis | Babesia microti | Erythrocytes, followed by systemic infection | Bite of ixodid ticks | Clindamycin plus quinine, chloroquine, pentamidine |

| Toxoplasmosis | Toxoplasma gondii | Systemic infection | Contact with infected animals; frequently found in rodents and cats | Dependent on nature of infection: pyrimethamine plus sulfadiazine or clindamycin, spiramycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole |

| Chagas’ disease | Trypanosoma cruzi | Systemic infection | Feces from reduviid bugs | Nifurtimox, allopurinol, benzimidazole |

| Leishmaniasis | Leishmania donovani, Leishmania tropica, Leishmania braziliensis | Systemic infection; each species targets different tissue | Bite of infected sandflies (genus Phlebotomus or Lutzomyia) | Stibogluconate, fluconazole, miltefosine, amphotericin |

Malaria

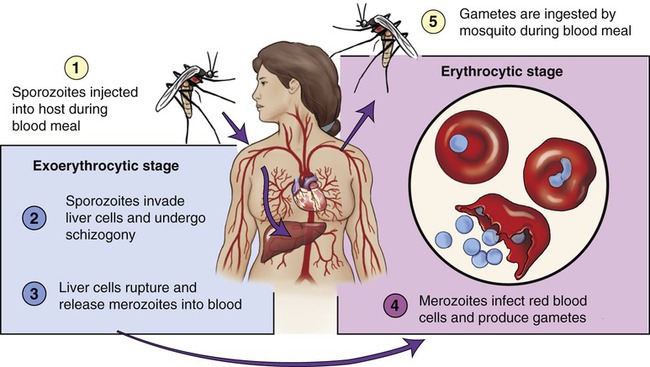

All species of the malaria parasite have similar life cycles, comprising three distinct stages, and characterized by alternating extracellular and intracellular forms (Figure 14.9). Malaria parasites are ingested by mosquitoes feeding on an infected human carrier; the mosquitoes then carry Plasmodium sporozoites in their salivary glands. In humans Plasmodium grows and multiplies originally in the liver and then in erythrocytes. Once in the blood the parasites grow inside the erythrocytes and destroy them, releasing daughter parasites referred to as merozoites, all of which continue the cycle, invading other red blood cells. It is the blood stage of the parasites that causes the symptoms of malaria. Once the gametocytes, a form of the blood stage, are picked up by the mosquito during a blood meal, the parasites start another, different cycle of growth and multiplication in the insect.

Severe Malaria

• Cerebral malaria, impairment of consciousness, seizures, coma, or other neurologic abnormalities

• Severe anemia due to hemolysis (destruction of erythrocytes)

• Hemoglobin in the urine (hemoglobinuria)

• Pulmonary edema or acute respiratory distress syndrome

• Abnormalities in blood coagulation and decrease in platelets

Toxoplasmosis

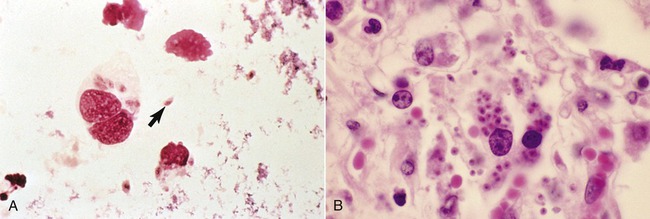

Toxoplasmosis is a disease caused by the protozoan Toxoplasma gondii (Figure 14.10), a single-celled, spore-forming parasite found throughout the world. The organisms carry out their reproductive cycle within the members of the cat family only. The cat is the definitive host. Transmission of toxoplasmosis to humans can occur in the following ways:

• Consumption of raw or undercooked meats, especially pork, lamb, or wild game

• Consumption of untreated water

• Fecal–oral route: After gardening, handling cats, cleaning cat litter boxes, or contaminating hands with anything that has come in contact with cat feces

• Mother-to-fetus, if the mother becomes infected during pregnancy

• Through organ transplant or blood transfusions; however, this mode of transmission is rare

Leishmaniasis

• Visceral leishmaniasis: A serious form and potentially fatal if untreated

• Cutaneous leishmaniasis: The most common form, causing a sore at the bite site that will heal in a few months to a year

• Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis: Causes widespread skin lesions and is difficult to treat

• Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis: Causes skin ulcers that spread and can cause tissue damage to the nose and mouth

Summary

• The circulatory system consists of the cardiovascular system (including the heart, blood, and blood vessels) and the lymphatic system (consisting of the lymph, lymphatic vessels, lymphatic tissues, and lymphatic organs).

• Endocarditis is generally caused by bacteria and fungi; myocarditis is most often caused by viruses and parasites; and pericarditis can be caused by bacteria, viruses, and sometimes by fungi.

• Exposure to blood or other bodily fluids can transmit infectious disease and present a problem to a wide range of occupations, specifically to healthcare workers, emergency response teams, public safety personnel, and teachers.

• Bacteremia is the presence of bacteria in the blood; septicemia is the multiplication of bacteria in the blood.

• Rheumatic fever can occur as a complication after a streptococcal infection. Gangrene is a complication of necrosis due to tissue death.

• Zoonotic diseases are transmitted from vertebrate animals to humans, and are an emerging field of conservation medicine.

• Vectors are animals that are capable of transmitting diseases, and include flies, mites, fleas, ticks, and rodents.

• Viruses cause a variety of circulatory diseases, and with the exception of infectious mononucleosis are most prevalent in tropical areas.

• Fungi can enter the human body through the lungs, gastrointestinal system, paranasal sinuses, or the skin. After entry the fungi spread via the bloodstream or the lymphatic system, at which time the infection becomes difficult to treat.

• Protozoa that cause disease in the circulatory system of humans have a complex life cycle and include species causing malaria, babesiosis, toxoplasmosis, Chagas’ disease, and leishmaniasis.

Review Questions

1. All of the following are symptoms of endocarditis except:

2. The toxic condition caused by the multiplication of bacteria in the blood is referred to as:

3. When microorganisms enter the circulatory system through lymphatic drainage and cause an infection the condition is called:

4. Rheumatic fever is an inflammatory disease and rare complication due to:

5. All of the following are considered to be zoonotic diseases except:

6. “Rabbit fever” is a zoonotic disease is caused by:

7. Rocky Mountain spotted fever is caused by:

8. Cytomegalovirus infections are caused by the human herpesvirus:

10. Which of the following is a disease caused by a protozoan?

11. A common complication of necrosis, often related to wounds, is referred to as __________.

12. Any infectious disease or infection that can be transmitted from vertebrate animals to humans is classified as __________.

13. When bacteria are found in the blood the condition is referred to as __________.

14. The toxic condition caused by the spread of bacteria or bacterial toxins from the site of infection is called __________.

15. Chagas’ disease is caused by __________.

16. Describe the different types of gangrene.

17. Describe the general principles of viral hemorrhagic fevers.

19. Describe the life cycle of the protozoan causing malaria.