Chapter 5 Impact of Age on Pharmacology

Fetus

A teratogen is defined as any agent that can cause malformations in a developing fetus.

Size of drug

Size of drug

The risk of a drug causing harm to the fetus is categorized using the system in Table 5-1, which is largely based on the evidence (or, most commonly, lack of evidence) of harm.

Note that relatively few drugs are at the extreme ends of the spectrum (either safe or absolutely contraindicated); this is typically because of a lack of good evidence. It is understandably difficult to conduct controlled trials in this population.

Note that relatively few drugs are at the extreme ends of the spectrum (either safe or absolutely contraindicated); this is typically because of a lack of good evidence. It is understandably difficult to conduct controlled trials in this population. The fact that most drugs fall in an intermediate area between safe and unsafe makes it difficult to decide whether a given drug should be used in pregnancy, and usually the decision depends on the risk-to-benefit assessment.

The fact that most drugs fall in an intermediate area between safe and unsafe makes it difficult to decide whether a given drug should be used in pregnancy, and usually the decision depends on the risk-to-benefit assessment. In some cases, not taking the medication may be more harmful to the pregnant patient (and fetus) than taking a medication with questionable risk.

In some cases, not taking the medication may be more harmful to the pregnant patient (and fetus) than taking a medication with questionable risk.

TABLE 5-1 Risk Categories and Descriptions for Use of Drugs in Pregnancy

| Risk Category | Description |

|---|---|

| A | Controlled studies in humans fail to demonstrate risk to the fetus in the first trimester or later trimesters, and the possibility of fetal harm appears remote. |

| B | Either animal reproduction studies have not demonstrated a fetal risk but there are no controlled studies in pregnant women, or animal reproduction studies have shown an adverse effect (other than a decrease in fertility) that was not confirmed in controlled studies in women in the first trimester (and there is no evidence of risk in later trimesters). |

| C | Either studies in animals have revealed adverse effects on the fetus (teratogenic or embryocidal or other) and there are no controlled studies in women, or studies in women and animals are not available. Drugs should be given only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus. |

| D | There is positive evidence of human fetal risk, but the benefits in pregnant women may be acceptable despite the risk (e.g., if the drug is needed in a life-threatening situation or for a serious disease for which safer drugs cannot be used or are ineffective). |

| X | Studies in animals or human beings have demonstrated fetal abnormalities or there is evidence of fetal risk based on human experience or both, and the risk of the use of the drug in pregnant women clearly outweighs any possible benefit. The drug is contraindicated in women who are or may become pregnant. |

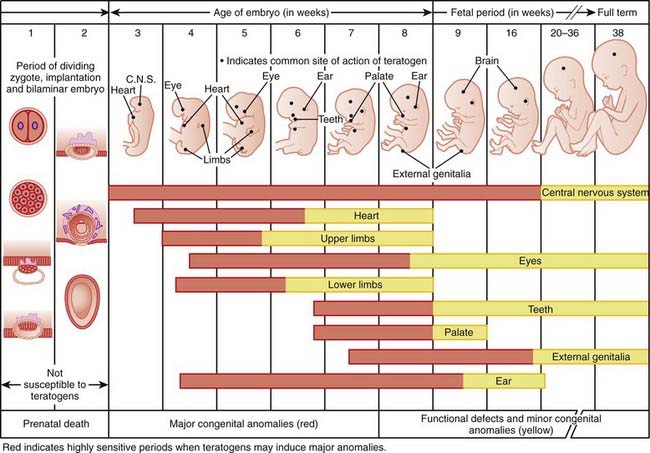

Timing of exposure is also important and is correlated with the stages of fetal development (Figure 5-1).

First 14 days: Typically this is all or none, meaning that exposure results in death of the embryo or has no effect. The common feature of these two extremes is that they go undetected; if the embryo dies the patient does not realize she was ever pregnant.

First 14 days: Typically this is all or none, meaning that exposure results in death of the embryo or has no effect. The common feature of these two extremes is that they go undetected; if the embryo dies the patient does not realize she was ever pregnant. Days 14-60 (organogenesis): Exposure to teratogens at this stage may lead to death of the fetus or significant malformations affecting structure or function.

Days 14-60 (organogenesis): Exposure to teratogens at this stage may lead to death of the fetus or significant malformations affecting structure or function. Day 61 onward: Exposure does not typically result in major structural malformations unless blood supply has been disrupted. However, from this point onward the major concern is fetotoxicity.

Day 61 onward: Exposure does not typically result in major structural malformations unless blood supply has been disrupted. However, from this point onward the major concern is fetotoxicity.

Neonates, Infants, and Children

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Neonates typically have reduced peristalsis, although gastrointestinal (GI) motility can be unpredictable among neonates. Slowed peristalsis delays gastric emptying and drug absorption.

Neonates typically have reduced peristalsis, although gastrointestinal (GI) motility can be unpredictable among neonates. Slowed peristalsis delays gastric emptying and drug absorption. Neonates have a higher pH in the stomach, beginning life with an essentially neutral pH and, after a period of instability, gradually developing more acidic levels until they reach adult values at around the age of 2. This increased pH can have several potential effects:

Neonates have a higher pH in the stomach, beginning life with an essentially neutral pH and, after a period of instability, gradually developing more acidic levels until they reach adult values at around the age of 2. This increased pH can have several potential effects:

It may reduce absorption of those drugs that require an acidic pH for their dissolution. This might be another reason for avoiding the use of tablets as a dosage form in infants.

It may reduce absorption of those drugs that require an acidic pH for their dissolution. This might be another reason for avoiding the use of tablets as a dosage form in infants.Distribution

Neonates, in particular, are born “wet,” with a much higher proportion of total body water than adults (80% versus 60%). This will affect the volume of distribution (Vd) of hydrophilic drugs.

Neonates, in particular, are born “wet,” with a much higher proportion of total body water than adults (80% versus 60%). This will affect the volume of distribution (Vd) of hydrophilic drugs.

Neonates also have lower levels of plasma proteins. Remember that drugs bound to plasma proteins are unable to cross membranes and interact with their receptors. Drugs that bind plasma proteins will therefore have a much larger free fraction, and this may lead to enhanced pharmacologic effect and increased risk of toxicity.

Neonates also have lower levels of plasma proteins. Remember that drugs bound to plasma proteins are unable to cross membranes and interact with their receptors. Drugs that bind plasma proteins will therefore have a much larger free fraction, and this may lead to enhanced pharmacologic effect and increased risk of toxicity.Metabolism

Drug metabolism is impaired at birth and gradually increases with time. The neonate is not born with a full complement of CYP450 enzymes but gradually acquires these enzymes through the first few weeks and months of life.

Drug metabolism is impaired at birth and gradually increases with time. The neonate is not born with a full complement of CYP450 enzymes but gradually acquires these enzymes through the first few weeks and months of life. Enzymes involved in glucuronidation take longer to develop, typically several months, and may not be fully operational for the first few years of life.

Enzymes involved in glucuronidation take longer to develop, typically several months, and may not be fully operational for the first few years of life.

Chloramphenicol and the “gray baby” syndrome is a classic example of the consequences of impaired glucuronidation in neonates. If dosage of this antibiotic is not appropriately determined, the drug can accumulate, leading to several serious outcomes (including a gray color) and potentially even death in the newborn.

Chloramphenicol and the “gray baby” syndrome is a classic example of the consequences of impaired glucuronidation in neonates. If dosage of this antibiotic is not appropriately determined, the drug can accumulate, leading to several serious outcomes (including a gray color) and potentially even death in the newborn.Excretion

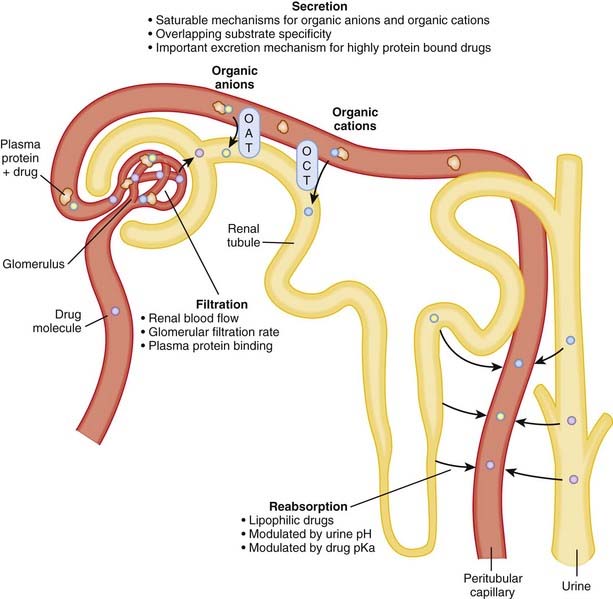

Renal function in infants is significantly reduced in the first year of life compared with that in adults. Full-term babies are born with only 30% of normal glomerular filtration rate, and in preterm babies this number is even lower. These differences can lead to dramatic increases in the elimination half-lives of drugs that rely on the kidneys for clearance.

Renal function in infants is significantly reduced in the first year of life compared with that in adults. Full-term babies are born with only 30% of normal glomerular filtration rate, and in preterm babies this number is even lower. These differences can lead to dramatic increases in the elimination half-lives of drugs that rely on the kidneys for clearance.

Other renal functions, most notably renal tubular secretion, may also not be fully developed in the newborn. Active tubular renal secretion is another process, distinct from glomerular filtration, by which drugs are excreted by the kidneys. Secretion occurs via a number of different transporters in the proximal tubule of the nephron, and studies in animals suggest that these transporters may be deficient in the newborn.

Other renal functions, most notably renal tubular secretion, may also not be fully developed in the newborn. Active tubular renal secretion is another process, distinct from glomerular filtration, by which drugs are excreted by the kidneys. Secretion occurs via a number of different transporters in the proximal tubule of the nephron, and studies in animals suggest that these transporters may be deficient in the newborn.Lactation

Elderly

Pharmacokinetics

As with the very young, the impact of age on the very old is broken down here using the ADME system.

Absorption

Distribution

Humans tend to dry out with age, so the elderly have a lower proportion of total body water than adults. Conversely, the elderly have a higher proportion of body fat. This means that hydrophilic drugs have a higher plasma concentration, and lipophilic drugs have a lower concentration, than in adults.

Humans tend to dry out with age, so the elderly have a lower proportion of total body water than adults. Conversely, the elderly have a higher proportion of body fat. This means that hydrophilic drugs have a higher plasma concentration, and lipophilic drugs have a lower concentration, than in adults. The elderly also tend to have lower albumin levels. However, they tend to have higher α1-acid glycoprotein levels, and the overall impact of plasma protein binding changes with age is not considered to be clinically significant in the healthy senior. However, in disease states, including liver failure, changes in plasma protein levels can be large enough to have clinical significance.

The elderly also tend to have lower albumin levels. However, they tend to have higher α1-acid glycoprotein levels, and the overall impact of plasma protein binding changes with age is not considered to be clinically significant in the healthy senior. However, in disease states, including liver failure, changes in plasma protein levels can be large enough to have clinical significance.Metabolism

Compared with adults, the elderly have impaired hepatic metabolic function for some drugs. This is because of a combination of a reduction in liver mass, hepatic blood flow, and activity of phase 1 enzymes (Box 5-2). Drugs that are metabolized by phase 2 enzymes appear to be less affected by advancing age.

Excretion

Declining renal function is a consistent but not universal consequence of the aging process. In many patients this decline in renal function begins in the early 20s and is a continuous process throughout life.

Declining renal function is a consistent but not universal consequence of the aging process. In many patients this decline in renal function begins in the early 20s and is a continuous process throughout life.Pharmacodynamics

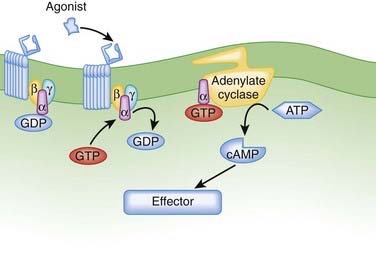

Reduced cardiac β receptor activity. Although findings for receptor density have not been consistent, coupling of β1 adrenoceptors to G proteins appears to be impaired with age. Remember from the introductory pharmacodynamics chapter that G proteins mediate the cellular actions of a receptor (Figure 5-3).

Reduced cardiac β receptor activity. Although findings for receptor density have not been consistent, coupling of β1 adrenoceptors to G proteins appears to be impaired with age. Remember from the introductory pharmacodynamics chapter that G proteins mediate the cellular actions of a receptor (Figure 5-3). Benzodiazepines. Elderly people appear to be more sensitive to the central nervous system (CNS) effects of benzodiazepines, and although this has been attributed to pharmacokinetic changes with age, studies also suggest that the clinical impact of aging is greater than would be expected from changes in pharmacokinetics alone. It is therefore hypothesized that pharmacodynamic responses to these drugs may be altered.

Benzodiazepines. Elderly people appear to be more sensitive to the central nervous system (CNS) effects of benzodiazepines, and although this has been attributed to pharmacokinetic changes with age, studies also suggest that the clinical impact of aging is greater than would be expected from changes in pharmacokinetics alone. It is therefore hypothesized that pharmacodynamic responses to these drugs may be altered.Summary and Clinical Context

Elderly patients are far more likely to be taking multiple medications, predisposing them to drug interactions.

Elderly patients are far more likely to be taking multiple medications, predisposing them to drug interactions. The elderly are far more likely to have kidney or liver disease, each of which would greatly accelerate the normal age-related reduction in the capacity of these organs to eliminate medications.

The elderly are far more likely to have kidney or liver disease, each of which would greatly accelerate the normal age-related reduction in the capacity of these organs to eliminate medications. The elderly are also far more likely to have cognitive deficits and are more likely to live alone, both of which would increase the risk of nonadherence to drug regimens.

The elderly are also far more likely to have cognitive deficits and are more likely to live alone, both of which would increase the risk of nonadherence to drug regimens.The combination of all these limitations has increased focus on the issue of appropriate prescribing in the elderly. Lists of inappropriate drugs used in elderly patients have been generated and updated by several groups. One of the early lists consisted of the Beers criteria; some examples of the most harmful drugs from this list are in Table 5-2.

TABLE 5-2 List of Drugs That Are Inappropriate for Elderly Patients (Beers Criteria)

| Drug | Class | Description of Concern |

|---|---|---|

| Indomethacin | NSAID | CNS side effects worse than other NSAIDs |

BZD, Benzodiazepine; CNS, central nervous system; GI, gastrointestinal; NSAID, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug; t1/2, half-life; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant.