30 Ilioinguinal and Iliohypogastric Neural Blockade

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

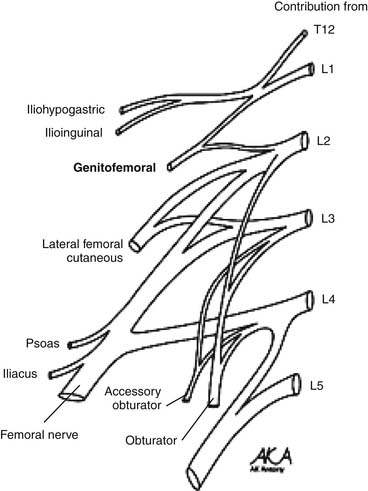

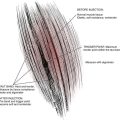

The ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves are branches of the lumbar plexus originating from the ventral ramus of L1 with occasional contributing fibers from T12 (Fig. 30-1). They emerge from the superolateral border of the psoas major muscle, course posterior to the medial arcuate ligaments, and anterolateral to the quadratus lumborum. Above the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), they pierce the transverse abdominal muscle or transversus abdominus.1,2

The iliohypogastric nerve continues between the transversus abdominis and internal oblique, dividing into lateral and anterior cutaneous branches. The lateral cutaneous branch perforates the internal and external oblique muscle above the iliac crest and innervates the posterolateral gluteal skin. The anterior cutaneous branch runs medial to the anterior superior iliac spine, perforating the external oblique aponeurosis above the superficial inguinal ring and innervating the suprapubic skin.1,2

The ilioinguinal nerve travels through the internal oblique muscle, traversing the inguinal canal below the spermatic cord. It exits through the superficial inguinal ring to innervate the proximal medial skin of the thigh. In males, it innervates the skin over the penile root and the upper scrotum. In females, it innervates the skin covering the mons pubis and the adjoining labia majora.1,2 The iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves occasionally interconnect along their courses, resulting in variations in the dermatomal distribution.3

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The vast majority of ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric neuralgias are iatrogenic. In 1942, Magee first described ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric neuralgias in scientific literature.4 Since then, a variety of etiologies have been detailed. Ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric neuropathies have been associated with a variety of lower abdominal surgeries.5 They may be the result of entrapment from sutures or staples, or result from adhesions, scarring, or inflammation. Neuroma formation, resulting from electrocauterization or laceration during open/laparoscopic procedures, may also contribute to this process.

Ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric neuralgias have been reported after various surgical procedures such as inguinal herniorrhaphy, appendectomy, abdominoplasty, needle bladder suspension, and iliac crest bone harvesting.6–9 A variety of obstetric surgical interventions such as total abdominal hysterectomy, pelvic lymphadenectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and other procedures involving Pfannenstiel incisions have also been associated with ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric neuralgias.10–13

The pathogenesis of these neuralgias depends on the etiology. In the case of entrapment, chronic compression may result in demyelination and axonal damage. A build-up of connective tissue in the endoneurium and perineurium may cause nerve thickening distal to the site of entrapment. In turn, this may affect the vascular supply through the vasa nervorum as well as axonal transport; ultimately disrupting neural function. Impulse generation and conduction may be affected causing symptoms.14 Neuroma formation may result from a transection of the nerve. When this occurs, the resulting axonal ends may continue to grow in a disorganized fashion. This, in turn, may result in a bulbous collection of unmyelinated fibers. These neuromas are far more mechanosensitive and thermosensitive than normal nerve endings and may produce spontaneous discharges resulting in neuropathy.15

Indications

Ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerve blocks are used as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool in the management of ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric neuropathies. They are used to determine true neuropathy, discriminate peripheral nerve pathology from radiculopathy, as well as to treat both chronic and acute groin pain. In addition, they may help to predict the outcome of permanent corrections such as neurectomy and neurolysis.

In combination with pharmacologic management, ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric blocks have been used to provide analgesia following surgeries such as inguinal herniorrhaphies, cesarean sections, orchiopexy, and total abdominal hysterectomies.16–19 In patients with chronic groin pain resulting from neuralgia, ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerve blocks have provided analgesia following failure of more conservative therapies.20

Technique

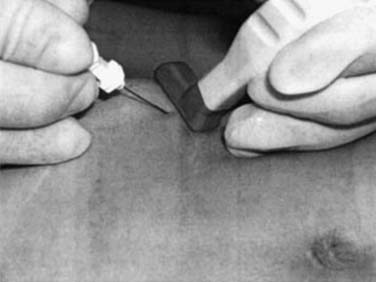

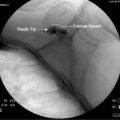

The first technique described relies on anatomic landmarks; the nerves are typically blocked 2 cm medial and superior to the anterior superior iliac spine (Fig. 30-2) along a line connecting the ASIS and the umbilicus. Here, the needle is inserted perpendicularly to the skin, noting penetration of each muscle fascial layer. Local anesthetic (10 mL with corticosteroid agent—typically methylprednisolone or triamcinolone 40 to 80 mg) is applied.

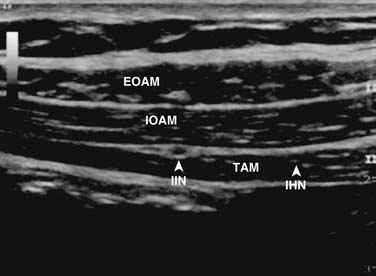

In the second technique, a linear probe of high frequency may be used because it provides good visualization of fascial and superficial structures.22 The probe is typically oriented obliquely, perpendicular to the inguinal ligament and to the anatomic course of both nerves. In this position, the probe is oriented roughly parallel to the abdominal muscle fibers, thereby improving image quality.22,23 The inferolateral part of the transducer may be placed slightly above the anterior superior iliac spine. Key structures to visualize include the anterior superior iliac spine, the peritoneum, the transversus abdominis, the internal oblique, and the external oblique.22–25

After identification of the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves, the block is performed using the out-of-plane (OOP) technique. With this technique, the needle is inserted perpendicular to the face of the transducer. With proper technique, it is possible to place the tip of the needle between the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves and inject about 10 mL of local anesthetic to achieve an adequate distribution. In chronic pain patients, it is possible to distinguish whether a pain syndrome is caused by either the ilioinguinal or iliohypogastric nerves by blocking each nerve with 1 mL of local anesthetic. For this purpose, diffusion of local anesthetic along a fascial plane should be avoided. Figure 30-3 demonstrates an ultrasound probe just above the ASIS with the needle inserted medial to the ASIS. Figure 30-4 demonstrates an ultrasound image of the anatomic structures at the level of the ASIS. On visualization of the key anatomic landmarks, the agent is injected between the internal oblique abdominal muscle and transverse abdominal muscle layers.22

It is worth noting that a branch of the deep circumflex artery lies between the internal oblique abdominal muscle and the transverse abdominal muscle, in the same plane as the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves.25 This has been suggested as a landmark in performing ultrasound-guided ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerve blocks. Injection of agent adjacent to this artery may result in anesthesia of both nerves.25 Use of power Doppler while using ultrasound will help localize this vascular structure. Avoid intra-arterial injection by aspiration prior to the injection of anesthetic/steroid agent.

It should be noted that in some individuals a genitofemoral nerve block may further alleviate pain. In the event that this too fails to improve symptoms, studies including electrodiagnostic studies and magnetic resonance imaging may be warranted to evaluate for radiculopathy, malignancy, or abscess formation.27

Treatment Options

Ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric neuralgias may be treated using a variety of medications and techniques. Commonly used medications to treat neuropathic pain include gabapentin, pregabalin, tricyclic antidepressants, and duloxetine (Cymbalta).28–30 Gabapentin is an alpha2-delta ligand thought to act on the voltage-gated calcium channel.28,30 Pregabalin binds with high affinity to the alpha2-delta site (an auxiliary subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels) in central nervous system (CNS) tissues. Binding to the alpha2-delta subunit may be involved in pregabalin’s antinociceptive and antiseizure effects in animal models. The exact mechanism of action of pregabalin is unknown.28,30 Tricyclic antidepressants are thought to affect pain pathways through their inhibition of serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake, affinity for the histamine H1-receptor, and effects on sodium channels.28,30 Although the exact mechanisms of the antidepressant, central pain inhibitory and anxiolytic actions of duloxetine in humans are unknown, these actions are believed to be related to its potentiation of serotonergic and noradrenergic activity in the CNS.28,30

Other options for treatment of neuropathic pain include implantation of peripheral nerve stimulators, spinal cord stimulation, and surgical neurectomy.31–37 In cases of well-defined neuromas that respond to anesthetic blocks, surgical neurectomy may be the preferred first line of therapy after medications.39

Surgical treatment involves the abatement of neuroma pain by relocating the painful neuroma to areas of low mechanical stress. The implied mechanism is that mechanically tethered neuromas produce pain when subjected to mechanical stress near joints, scars, and structures with wide range of motion. Nerves may be cut back and implanted in healthy, well-vascularized muscle. The cut ends may again sprout and a new neuroma may form. However, the chances are reduced that the nerve will be subject to tension and shearing forces which are likely to play a role in neuropathic pain generation.39

1. Standring S. Posterior abdominal wall and retroperitoneum. In: Gray H., Standring S., Ellis H., Berkovitz B.K.B., editors. Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. London: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005:1113.

2. Moore K.L., Dalley A.F. Abdomen. In: Kelly P.J., editor. Clinically Oriented Anatomy. 5th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:207.

3. al-dabbagh A.K. Anatomical variations of the inguinal nerves and risks of injury in 110 hernia repairs. Surg Radiol Anat. 2002;24(2):102-107.

4. Magee R.K. Genitofemoral causalgia: A new syndrome. Can Med Assoc J, 46. 1942:326-329.

5. Waldman S.D. Ilioinguinal-iliohypogastric and genitofemoral nerve blocks. In: Lampert R., editor. Interventional Pain Management. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2001:508.

6. Liszka T.G., Dellon A.L., Manson P.N. Iliohypogastric nerve entrapment following abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93(1):181-184.

7. Melville K., Schultz E.A., Dougherty J.M. Ilionguinal-iliohypogastric nerve entrapment. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19(8):925-929.

8. Monga M., Ghoniem G.M. Ilioinguinal nerve entrapment following needle bladder suspension procedures. Urology. 1994;44(3):447-450.

9. Bents R.T. Ilioinguinal neuralgia following anterior iliac crest bone harvesting. Orthopedics. 2002;25(12):1389-1390.

10. Cardosi R.J., Cox C.S., Hoffman M.S. Postoperative neuropathies after major pelvic surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(2):240-244.

11. El-Minawi A.M., Howard F.M. Iliohypogastric nerve entrapment following gynecologic operative laparoscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:871.

12. Sippo W.C., Burghardt A., Gomez A.C. Nerve entrapment after Pfannenstiel incision. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;157(2):420-421.

13. Tosun K., Schafer G., Leonhartsberger N., et al. Treatment of severe bilateral nerve pain after Pfannenstiel incision. Urology. 2006;67(3):623. e5,623.e6

14. Seid A.S., Amos E. Entrapment neuropathy in laparoscopic herniorrhaphy. Surg Endosc. 1994;8(9):1050-1053.

15. Benzon H.T., Raja S.N., Molloy R.E., et al. Truncal blocks. In: Andjelkovic N., editor. Essentials of Pain Medicine and Regional Anesthesia. Philadelphia: Elsevier, Churchill Livingstone; 2005:636.

16. Abad-Torrent A., Calabuig R., Sueiras A., et al. Efficacy of the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric block in the treatment of the postoperative pain of inguinal herniorrhaphy. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 1996;43(9):318-320.

17. Oriola F., Toque Y., Mary A., et al. Bilateral ilioinguinal nerve block decreases morphine consumption in female patients undergoing nonlaparoscopic gynecologic surgery. Anesth Analg. 2007;104(3):731-734.

18. Lipp A. Ilioinguinal nerve block for orchidopexy. Anaesthesia. 1998;53(5):515-516.

19. Gucev G., Yasui G.M., Chang T.Y., Lee J. Bilateral ultrasound-guided continuous ilioinguinal-iliohypogastric block for pain relief after cesarean delivery. Anesth Analg. 2008;106(4):1220.

20. Miyazaki F., Shook G. Ilioinguinal nerve entrapment during needle suspension for stress incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80(2):246-248.

21. Choi P.D., Nath R., Mackinnon S.E. Iatrogenic injury to the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves in the groin: A case report, diagnosis, and management. Ann Plast Surg. 1996;37(1):60-65.

22. Hu P., Harmon D., Frizelle H. Ultrasound guidance for ilioinguinal/iliohypogastric nerve block: A pilot study. Ir J Med Sci. 2007;176(2):111-115.

23. Eichenberger U., Greher M., Kirchmair L., et al. Ultrasound-guided blocks of the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerve: Accuracy of a selective new technique confirmed by anatomical dissection. Br J Anaesth. 2006;97(2):238-243.

24. Peng P.W., Tumber P.S. Ultrasound-guided interventional procedures for patients with chronic pelvic pain—a description of techniques and review of literature. Pain Physician. 2008;11(2):215-224.

25. Gofeld M., Christakis M. Sonographically-guided ilioinguinal nerve block. J Ultrasound Med. 2006;25(12):1571-1575.

26. Waldman S.D. Atlas of Interventional Pain Management, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2004. 294–300

27. Gallagher R.M. Management of neuropathic pain: Translating mechanistic advances and evidence-based research into clinical practice. Clin J Pain, Suppl 1. 2006:S2-8.

28. Benito-Leon J., Picardo A., Garrido A., Cuberes R. Gabapentin therapy for genitofemoral and ilioinguinal neuralgia. J Neurol. 2001;248(10):907-908.

29. Dworkin R.H., O’Connor A.B., Backonja M., et al. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: Evidence-based recommendations. Pain. 2007;132(3):237-251.

30. Rauchwerger J.J., Giordano J., Rozen D., et al. On the therapeutic viability of peripheral nerve stimulation for ilioinguinal neuralgia: Putative mechanisms and possible utility. Pain Pract. 2008;8(2):138-143.

31. Pappalardo G., Frattaroli F.M., Mongardini M., et al. Neurectomy to prevent persistent pain after inguinal herniorraphy: A prospective study using objective criteria to assess pain. World J Surg. 2007;31(5):1081-1086.

32. Tsakayannis D.E., Kiriakopoulos A.C., Linos D.A. Elective neurectomy during open, “tension free” inguinal hernia repair. Hernia. 2004;8(1):67-69.

33. Trescot A.M. Cryoanalgesia in interventional pain management. Pain Physician. 2003;6(3):345-360.

34. Rozen D., Ahn J. Pulsed radiofrequency for the treatment of ilioinguinal neuralgia after inguinal herniorrhaphy. Mt Sinai J Med. 2006;73(4):716-718.

35. Amid P.K. Causes, prevention, and surgical treatment of postherniorrhaphy neuropathic inguinodynia: Triple neurectomy with proximal end implantation. Hernia. 2004;8(4):343-349.

36. Whiteside J.L., Barber M.D. Ilioinguinal/iliohypogastric neurectomy for management of intractable right lower quadrant pain after cesarean section: A case report. J Reprod Med. 2005;50(11):857-859.

37. Willschke H., Bosenberg A., Marhofer P. Ultrasonographic-guided ilioinguinal/iliohypogastric nerve block in pediatric anesthesia: What is optimal volume. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:1680-1684.

38. Loeser J.D., Butler S.H., Chapman R., Turk D.C. Bonica’s Management of Pain, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. 2013–2014