Herpes zoster

Rana Majd Mays, Erik T. Petersen, Rachel A. Gordon and Stephen K. Tyring

Management strategy

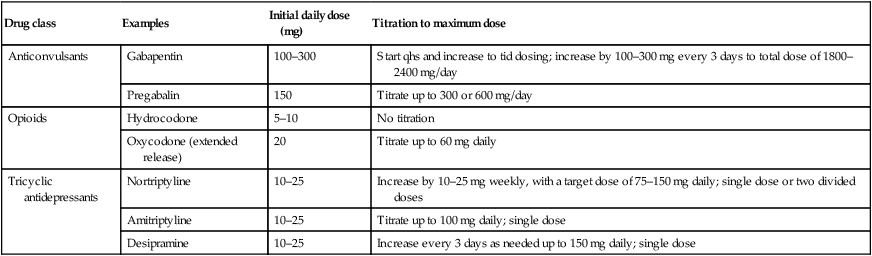

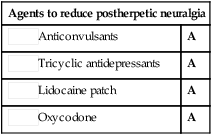

Current therapeutic options for PHN include the anticonvulsants gabapentin and pregabalin, opioid analgesics, tricyclic antidepressants (Table 101.1), lidocaine patch 5%, and capsaicin cream. Choice of therapy should be guided by considering a patient’s comorbidities, drug adverse event profiles, and preference. Combination therapy is common in clinical practice, but there is no evidence base to support this practice.

Table 101.1

Treatment options for postherpetic neuralgia

| Drug class | Examples | Initial daily dose (mg) | Titration to maximum dose |

| Anticonvulsants | Gabapentin | 100–300 | Start qhs and increase to tid dosing; increase by 100–300 mg every 3 days to total dose of 1800–2400 mg/day |

| Pregabalin | 150 | Titrate up to 300 or 600 mg/day | |

| Opioids | Hydrocodone | 5–10 | No titration |

| Oxycodone (extended release) | 20 | Titrate up to 60 mg daily | |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | Nortriptyline | 10–25 | Increase by 10–25 mg weekly, with a target dose of 75–150 mg daily; single dose or two divided doses |

| Amitriptyline | 10–25 | Titrate up to 100 mg daily; single dose | |

| Desipramine | 10–25 | Increase every 3 days as needed up to 150 mg daily; single dose |

First-line therapies

Valacyclovir compared with acyclovir for improved therapy for herpes zoster in immunocompetent adults.

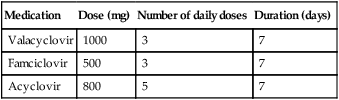

Valacyclovir is comparable to acyclovir in the resolution of zoster eruption (Table 101.2), but it accelerates the resolution of pain compared to acyclovir and is more convenient.

Table 101.2

First-line therapy for acute herpes zoster

| Medication | Dose (mg) | Number of daily doses | Duration (days) |

| Valacyclovir | 1000 | 3 | 7 |

| Famciclovir | 500 | 3 | 7 |

| Acyclovir | 800 | 5 | 7 |

Antiviral therapy for herpes zoster: randomized, controlled clinical trial of valacyclovir and famciclovir therapy in immunocompetent patients 50 years and older.

Tyring SK, Beutner KR, Tucker BA, Anderson WC, Crooks RJ. Arch Fam Med 2000; 9: 863–9.

Valacyclovir is comparable to famciclovir in the resolution of zoster-associated pain and PHN.

Oral acyclovir therapy accelerates pain resolution in patients with herpes zoster: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials.

Wood MJ, Kay R, Dworkin RH, Soong SJ, Whitley RJ. Clin Infect Dis 1996; 22: 341–7.

In four placebo-controlled studies acyclovir was clearly shown to accelerate pain resolution.

Second-line therapies

Gabapentin versus nortriptyline in post-herpetic neuralgia patients: a randomized, double blind clinical trial: The GONIP Trial.

Chandra K, Shafiq N, Pandhi P, Gupta S, Malhotra S. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2006; 44: 358–63.

Gabapentin and nortriptyline are equally efficacious, but gabapentin is better tolerated.

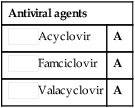

Acyclovir

Acyclovir Famciclovir

Famciclovir Valacyclovir

Valacyclovir

Anticonvulsants

Anticonvulsants Tricyclic antidepressants

Tricyclic antidepressants Lidocaine patch

Lidocaine patch Oxycodone

Oxycodone

Vaccination of adults

Vaccination of adults Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids Contact with varicella or with children

Contact with varicella or with children Topical capsaicin

Topical capsaicin Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory cream

Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory cream Tramadol

Tramadol Sympathetic nerve block

Sympathetic nerve block Transcutaneous electrical stimulation

Transcutaneous electrical stimulation