Chapter 63 Headaches in Infants and Children

Epidemiology

Headaches are common during childhood and become increasing more frequent during adolescence. The prevalence of headache ranges from 37 to 51 percent in 7-year-olds, gradually rising to 57–82 percent by age 15. Recurring or frequent headaches occurred in 2.5 percent of 7-year-olds and 15 percent of 15-year-olds [Bille, 1962]. Before puberty, boys are affected more frequently than girls, but after puberty, headaches occur more frequently in girls [Deubner, 1977; Sillanpaa, 1983; Dalsgaard-Nielsen, 1970; Laurell et al., 2004].

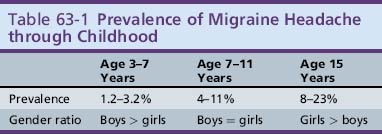

The prevalence of migraine headache steadily increases through childhood and the male:female ratio shifts during adolescence. The prevalence rises from 3 percent at age 3–7 years to 4–11 percent by age 7–11, and up to 8–23 percent during adolescence (Table 63-1). The mean age of onset of migraine is 7.2 years for boys and 10.9 years for girls [Dalsgaard-Nielsen, 1970; Lipton et al., 1994; Mortimer et al., 1992; Valquist, 1955; Small and Waters, 1974; Sillanpaa, 1976; Stewart et al., 1991; Stewart et al., 1992].

Data regarding tension-type headache is limited. Two studies including school-aged children of 7–19 years, and using the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-2) criteria, found the 1-year prevalence of tension-type headache to be 10–23 percent. The prevalence of tension-type headache increased with age in both boys and girls, up to age 11 years, and thereafter only increased in girls [Laurell et al., 2004; Zwart et al., 2004].

Chronic daily headache, defined as more than 15 headache days/month for more than 4 months, occurs in 1–2 percent of adolescents [Wang et al., 2006, 2009].

Classification

The International Headache Society’s comprehensive classification system for the spectrum of primary and secondary headache disorders is available on their website (http://ihs-classification.org/en) (Box 63-1). There are three major categories: the primary headaches, the secondary headaches, and the cranial neuralgias. Each headache category is carefully defined, subclassified, and annotated.

Box 63-1 International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-2)

For example, the classification for the primary headache disorder, migraine, is subclassified into migraine without aura, migraine with aura, and the childhood periodic syndromes that are commonly precursors of migraine. Migraine with aura is further divided into subgroups based upon current views of the pathophysiology of migraine. The visual, sensory, motor, or psychic phenomena that herald the onset of a migraine attack are all included under migraine with aura (Box 63-2). A migraine attack accompanied by hemiparesis (e.g., familial hemiplegic migraine [FHM]) falls in the category of migraine with aura, although alternative explanations for hemiparesis with headache must be carefully sought before the diagnosis of FHM can be accepted.

Box 63-2 2003 International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-2): Migraine

Alternating hemiparesis of childhood (AHC) is a rare and bizarre entity, once thought to be a migrainous phenomenon. AHC is now viewed as a metabolic disorder, probably due to a mitochondrial disorder or a channelopathy. Recently, however, a novel ATP1A2 mutation within one kindred, with features that bridged the phenotypic spectrum between AHC and FHM, has been reported and may draw AHC back into the migraine spectrum [Swoboda et al., 2004; Bassi et al., 2004].

Clinical Classification

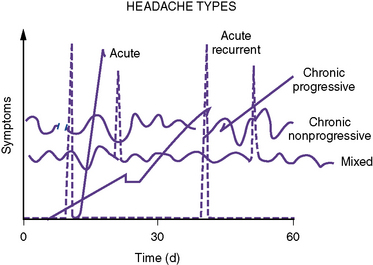

A useful clinical classification system was proposed by Rothner; it divides headache into five temporal patterns (Figure 63-1): acute, acute recurrent, chronic progressive, chronic nonprogressive, and mixed. Each of these temporal patterns suggests differing pathophysiologic processes and has distinctive differential diagnoses (Box 63-3).

Box 63-3 Differential Diagnosis of the Five Temporal Patterns

Diagnostic Criteria

The ICHD-2 established the diagnostic criteria for the primary headache disorders, incorporating many developmentally sensitive changes compared to previous criteria, and thus improving applicability to children and adolescents while maintaining specificity and improving sensitivity (Box 63-4) [Oleson, 2004]. For example, the criteria accept that pediatric migraine may be brief (approximately 1 hour), as opposed to a 4-hour duration for adults; may be bifrontal in location (under age 15 years); and may have associated symptoms of photophobia and phonophobia, which may be inferred by the child’s behavior, such as withdrawing to a dark, quiet room to rest during the headache attack.

Box 63-4 ICHD-2 Diagnostic Criteria for the Primary Headache Disorders: Migraine and Tension-Type

Pediatric Migraine without Aura

ICHD-2 also includes criteria for cyclical vomiting and abdominal migraine (Box 63-5 and Box 63-6).

Box 63-5 ICHD-2 Criteria for Cyclical Vomiting Syndrome

Description

Box 63-6 ICHD-2 Criteria for Abdominal Migraine

Description

Evaluation of the Child with Headache

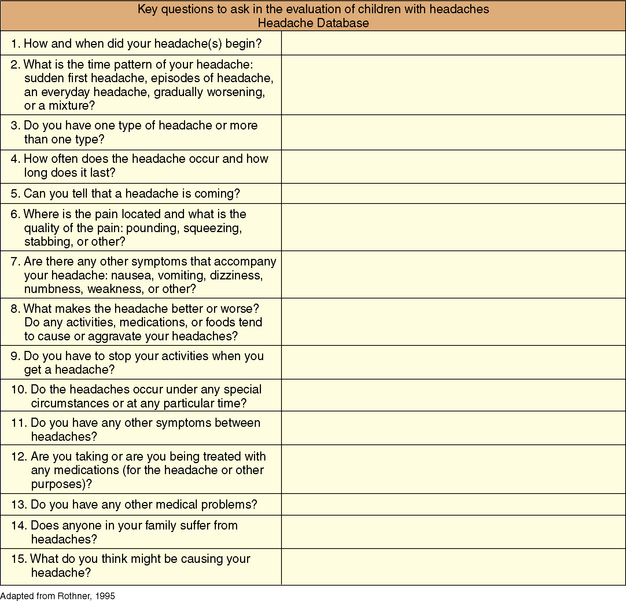

The evaluation of a child with headaches follows the traditional medical model and begins with a thorough medical history and complete physical and neurologic examination. The brief series of questions shown in Figure 63-2 provides a logical framework for evaluating headaches and generally yields sufficient information to diagnose most primary headaches and reveal clues to presence of secondary headache disorders.

Fig. 63-2 Key questions to ask in the evaluation of children with headaches.

(Adapted from Rothner AD. The evaluation of headaches in children and adolescents. Seminars in Pediatric Neurology 1995; 2:109–118.) [Rothner, 1995]

The role of ancillary diagnostic studies, such as laboratory testing, electroencephalography (EEG), and neuroimaging, has been extensively reviewed [Lewis et al., 2002]. This American Academy of Neurology (AAN) Practice Parameter determined that there is inadequate documentation in the literature to support any recommendation as to the appropriateness of routine laboratory studies (e.g., hematology or chemistry panels) or performance of lumbar puncture. Routine EEG is not recommended as part of the headache evaluation. Data compiled from eight studies showed that the EEG was not necessary for differentiation of primary headache disorders (e.g., migraine, tension-type) from secondary headache due to structural disease involving the head and neck, or from headaches due to a psychogenic etiology. In addition, EEG is unlikely to define or determine an etiology of the headache or to distinguish migraine from other types of headaches. Furthermore, in those children undergoing evaluation for recurrent headache who were found to have paroxysmal EEGs, the risk of future seizures is negligible.

Primary Headache Syndromes

Migraine

Migraine is the most common acute recurrent headache syndrome. The classification of migraine is shown in Box 63-2 and the cardinal diagnostic features are shown in Box 63-4.

Pathophysiology

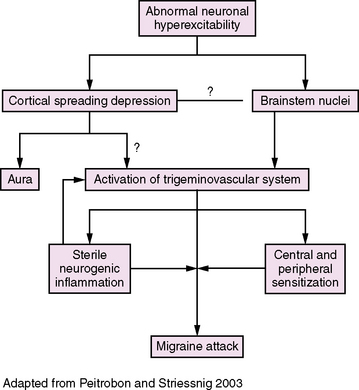

Incompletely understood, migraine is thought to be a complex, primary, neuroglial process (Figure 63-3) [Pietrobon and Striessnig, 2003; Silberstein, 2004; Goadsby et al., 2009]. The principal underlying phenomenon of migraine is hyperexcitable neurons. Polygenic influences produce disturbances of neuronal ion channels (e.g., sodium, calcium), leading to episodes of cortical spreading depression (CSD) and activation of the “trigeminovascular system.”

Fig. 63-3 Migraine pathophysiology.

(Adapted from Pietrobon D, Striessnig J. Neurobiology of migraine. Nat Rev 2003;4:386.)

Neurogenic inflammation alone may be an insufficient explanation for the severity and quality of pain in migraine. One of the striking symptoms experienced during an attack of migraine is that seemingly innocuous activities, such as coughing, walking up stairs, or bending over, greatly intensify the pain. This observation, coupled with elegant research, has led to the concepts of “sensitization” of trigeminal vascular afferents, whereby both peripheral and central afferent circuits become exceptionally sensitive to mechanical, thermal, and chemical stimuli. These circuits become so sensitive that virtually any stimulation is perceived as painful: the concept of “allodynia” [Burstein et al., 2000, 2004; Burstein and Jakubowski, 2004].

Clinical Manifestations

Migraine without aura

The diagnostic criteria for migraine without aura are shown in Box 63-4.

Migraine headaches typically last for hours, even days (1–72 hours), but do not, generally, occur more frequently than 6–8 times per month. More than 8–10 attacks per month must warrant consideration of alternative diagnoses, such as organic conditions (i.e., idiopathic intracranial hypertension) or the spectrum of chronic daily headache [Gladstein et al., 1997; American College of Emergency Physicians, 1996].

Migraine with aura

Approximately 14–30 percent of children will report visual disturbances, distortions, or obscuration before or as the headache begins (Box 63-7) [Lewis, 1995]. The aura (“cool breeze”) is, however, an inconsistent feature in childhood and adolescents. The presence of an aura must be elicited with very specific questions: “Do you have spots, colors, lights, dots in your eyes before or as you are getting a headache?”

Basilar-Type Migraine

Also known as basilar artery or vertebrobasilar migraine, this clinical entity is the most common of migraine variants and is estimated to represent 3–19 percent of all migraine [Bickerstaff, 1961; Lapkin and Golden, 1978; Golden and French, 1975]. This wide range of frequency relates to the rigorousness of the definition. Some authors consider any headache with dizziness to be within the spectrum of basilar-type migraine (BTM), whereas others require the presence of clear signs and symptoms of posterior fossa involvement before establishing this diagnosis. The ICHD-2 criteria require two or more symptoms and emphasize bulbar and bilateral sensorimotor features (Box 63-8).

| Vertigo | 73% |

| Nausea or vomiting | 30–50% |

| Ataxia | 43–50% |

| Visual field deficits | 43% |

| Diplopia | 30% |

| Tinnitus | 13% |

| Vertigo | 73% |

| Hearing loss | * |

| Confusion | 20% |

| Dysarthria | * |

| Weakness (hemiplegia, quadriplegia, diplegia) | 20% |

| Syncope | * |

The pathogenesis of BTM is not well understood. While focal cortical processes, oligemia, or depolarization can explain the deficits in hemiplegic migraine, the posterior fossa signs of BTM are more problematic. A single case report of a 25-year-old woman with BTM exists, wherein transcranial Doppler and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) were performed through the course of a BTM attack. These data suggest decreased posterior cerebral artery perfusion through the aura phase at a time when the patient described was experiencing transient bilateral blindness and ataxia [La Spina et al., 1997].

Hemiplegic Migraine

Familial Hemiplegic Migraine

FHM is an uncommon autosomal-dominant form of migraine headache, in which the aura has a “stroke-like” quality, producing some degree of hemiparesis. The nosology is somewhat misleading since there is actually a wide diversity of focal symptoms and signs that can accompany this migraine variant, beyond motor deficits. Barlow proposed the more appropriate term “hemi-syndrome migraine” to emphasize the diversity of associated symptoms, but this was not adopted [Barlow, 1984]. ICHD-2 clearly requires that “some degree of hemiparesis” must be present.

A series of exciting discoveries into the molecular genetics of FHM have broadened our understanding of the fundamental mechanisms of migraine and demonstrated the overlap with other paroxysmal disorders, such as acetazolamide-responsive episodic ataxia [Joutel et al., 1993]. Genetic linkage to chromosome 19p13 has been identified in half of the known FHM pedigrees. FHM types 2 and 3 are clinically quite similar but have distinctly different molecular mechanisms. FMF type 2 is due to point mutation of the alpha-2 subunit of the sodium-potassium pump (ATP1A2) gene on chromosome 1q21–23, and type 3 is due to a sodium channel gene mutation (SCN1A) [Ophoff et al., 1997; Gardner et al., 1997; Dichgans et al., 2005]. More genotypes will likely be identified with broadening of the phenotype. The chromosome 19 defect (FHM type 1) produces a missense mutation in a neuronal calcium channel gene (CACNA1A), providing compelling evidence that FHM represents a channelopathy. These discoveries have revolutionized our understanding of migraine and may open new territory for pharmacologic interventions.

The appearance of acute, focal neurologic deficits in the setting of headache in an adolescent necessitates vigorous investigation for disorders such as intracranial hemorrhage, stroke, tumor, vascular malformations, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, or focal infection. Complex partial seizure or drug intoxication with a sympathomimetic must also be considered. Neuroimaging (magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] and magnetic resonance angiography [MRA]) and EEG may be indicated. Investigations for embolic sources or hypercoagulable states are likewise appropriate. Molecular genetic testing is now available for the three genes known to be associated with FHM: CACNA1A (FHM 1), ATP1A2 (FHM 2), and SCN1A (FHM 3) [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bookshelf/br.fcgi?book=gene&part=fhm].

Alternating Hemiplegia of Childhood

Children with AHC have attacks of paralysis: hemiparesis, monoparesis, diparesis, ophthalmoparesis, or bulbar paralysis, which may be accompanied by variable tone changes (flaccid, spastic, or rigid). A variety of paroxysmal involuntary movements, including chorea, athetosis, dystonia, nystagmus, and respiratory irregularities (hyperpnea), can be seen. The attacks of paralysis can be brief (minutes) or prolonged (days), and are potentially life-threatening during periods of bulbar paralysis. Curiously, the attacks generally subside following sleep. Affected children are frequently developmentally challenged [Verret and Steele, 1971; Aicardi et al., 1995].

A recent comprehensive report of 103 children who met existing criteria for AHC focused on the earliest manifestations of symptoms and evolution of features over time. Paroxysmal eye movements were the most frequent early symptom, manifesting in the first 3 months of life in 83 percent of patients. Hemiplegic episodes appeared by 6 months of age in 56 percent of infants. Distinct convulsive episodes with altered consciousness, believed to be epileptic in nature, were reported in 41 percent of patients. Static features of AHC included ataxia (96 percent) and cognitive impairment (100 percent). MRI studies were generally normal (78 percent). Treatments included flunarizine, benzodiazepines, carbamazepine, barbiturates, and valproic acid. Flunarizine was the most effective agent, but perceived improvement occurred in only 60 percent of patients [Sweney et al., 2009].

The link to migraine was tenuous, but was based upon the presence of a high prevalence of migraine in the families of affected children and upon cerebral blood flow data that suggest a “migrainous” mechanism. In 1997, an international workshop was conducted to address the various hypotheses surrounding AHC and proposed mechanisms, including channelopathy, mitochondrial cytopathy, and cerebrovascular dysfunction. Channelopathy was suggested as the most likely explanation [Rho and Chugani, 1998]. A novel ATP1A2 mutation in a kindred with features that bridged the phenotypic spectrum between AHC and FHM has been reported. This observation may draw AHC back into the migraine spectrum; however, at this point the underlying molecular mechanisms of AHC are unknown [Wang et al., 2006].

Confusional Migraine

The clinical entity was first described in 1970 by Gascon and Barlow, who reported a series of children, aged 8–16 years, with acute confusional states lasting 4–24 hours, and associated with agitation and aphasia. The authors suggested that the confusional state was a manifestation of juvenile migraine [Garcon and Barlow, 1970]. Ehyai and Fenichel later introduced the term acute confusional migraine [Ehyai and Fenichel, 1978]. Subsequent reports have broadened the clinical phenomenology to include blindness, paresthesias, hemiparesis, and amnesia. Amnesia can be such a prominent feature that Jenson proposed the term transient global amnesia of childhood, but amnesia is only part of the clinical spectrum [Jensen, 1980].

There is clear link to head trauma in many cases [Ferrera and Reicho, 1996]. The term “footballer’s migraine” is applied in Europe when a soccer player, after “heading” the ball, develops acute confusional state with headache. Similar phenomena may follow other causes of minor head injury. This variant should be viewed within the spectrum of trauma-triggered migraine.

Acute confusional states in children and adolescents warrant aggressive investigation for encephalitis, brain abscess, drug intoxication, cerebrovascular disease, vasculitis, or metabolic encephalopathies [Amit, 1988]. Particular attention must be focused on the possibility of complex partial seizures or postictal states.

Childhood “Periodic Syndromes”

Cyclical Vomiting Syndrome

Cyclical vomiting syndrome (CVS) is a disorder characterized by recurrent, self-limiting-episodes of intense vomiting (more than four emeses/hour), recognizable by their stereotypical time of onset, duration, and symptomatology within the individual (see Box 63-5). The vomiting is uniquely intense and the subjective nausea disabling; the resultant dehydration often necessitates hospital-based treatment. The attacks are accompanied by pallor, listlessness, anorexia, abdominal pain, retching, headache, and photophobia. The interval between attacks is 2–4 weeks and a typical attack lasts 24–48 hours. The children are, by definition, healthy between attacks.

A recent practice guideline provides expert opinion regarding the evaluation and treatment of children with CVS [Li et al., 2008]. A thorough diagnostic evaluation must be performed to rule out intermittent bowel obstruction, elevated intracranial pressure, epilepsy, and metabolic disorders, such as urea cycle defects and organic acidurias. There is clearly a subset of children with a cyclic vomiting pattern who have underlying metabolic disorders.

Abdominal Migraine

Abdominal migraine is an addition to the ICHD-2. The diagnostic criteria for abdominal migraine are listed in Box 63-6. This clinical entity is characterized by recurrent episodes of midline, epigastric abdominal pain lasting 1–72 hours. The pain is of moderate to severe intensity and is associated with vasomotor symptoms (e.g., flushing, pallor), as well as nausea and vomiting. The patients are well between attacks. Thorough gastrointestinal and renal investigations must be conducted before this diagnosis can be entertained. In a recent series of patients with idiopathic chronic abdominal pain collected from an academic pediatric gastrointestinal clinic, 4–15 percent were found to meet diagnostic criteria for abdominal migraine, suggesting that abdominal migraine is an underdiagnosed cause of recurrent abdominal pain in children in the United States.

Benign Paroxysmal Torticollis

Benign paroxysmal torticollis (BPT) is a rare paroxysmal dyskinesia characterized by attacks of head tilt alone or tilt accompanied by vomiting and ataxia, which may last hours to days [Chaves-Carballo, 1996]. Other torsional or dystonic features, including truncal or pelvic posturing, were described by Chutorian [Chutorian, 1974]. Attacks first manifest during infancy, between 2 and 8 months of age.

The original descriptions of BPT by Snyder suggested a form of labyrinthitis and demonstrated abnormal vestibular reflexes [Snyder, 1969]. A recent case series of 10 patients followed longitudinally, plus a literature review of another 93 cases, has expanded our understanding of BPT. The authors found that attacks usually lasted for less than 1 week, but often recurred every few days or every few months. The episodes improved by age 2 years and typically ended by age 3. There was a very frequent family history of migraine. Developmental assessments, available only in the authors’ 10 cases, showed accompanying gross motor delays in 50 percent of children, with additional fine motor delays in 30 percent. Curiously, as BPT improved, so did the gross motor delays and the fine motor delays in about one-half to one-third of the children. The authors concluded that BPT is likely an “age-sensitive, migraine-related disorder, commonly accompanied by delayed motor development” [Rosman et al., 2009].

The link to migraine is strengthening. In addition to a frequent family history of migraine, intriguing molecular genetic information has been reported, in which four children with benign paroxysmal torticollis were shown to be linked to familial CACNA1A mutations [Giffin et al., 2002]. BPT is likely a migraine precursor within the spectrum of basilar-type migraine and benign paroxysmal vertigo.

Management of Pediatric Migraine

Once the diagnosis of migraine is established and appropriate reassurances have been provided, a balanced and individually tailored treatment plan can be instituted. The first step is to appreciate the degree of disability imposed by the patient’s headache. Understanding of the impact of the headache on the quality of life will guide in the decisions regarding the most appropriate therapeutic course [Powers et al., 2003, 2004].

To achieve these goals, it is becoming increasingly clear that a balanced treatment must include biobehavioral strategies and nonpharmacologic methods, as well as pharmacologic measures. Biobehavioral treatments include biofeedback, stress management, sleep hygiene, exercise, and dietary modifications (Box 63-9) [Holroyd and Mauskop, 2003].

Biofeedback has demonstrated effectiveness in the treatment of both adults and children with migraine in controlled trials. While the physiological basis for its effectiveness is unclear, data suggest that levels of plasma beta-endorphin can be altered by biofeedback therapies [Baumann, 2002]. Biofeedback therapies commonly use electrical devices that provide audio or visual displays to demonstrate a physiological effect. Thermal biofeedback is the most commonly used technique in pediatrics, wherein children are taught to raise the temperature of one of their fingers. These techniques can easily be taught to children and their use is associated with fewer and briefer migraine headaches. Once taught these methods, the children can manage future headaches, allowing them to feel greater control of their health.

Stress management and relaxation therapies use techniques such as progressive relaxation, self-hypnosis, and guided imagery. Controlled trials have reported relaxation therapies to be as effective in reducing the frequency of migraine attacks as the beta-blocker propranolol [Olness et al., 1987].

Sleep disturbances occur in 25–40 percent of children with migraine. One recent study found too little sleep (42 percent), bruxism (29 percent), co-sleeping (25 percent), and snoring (23 percent) in a population of 118 children. When children with migraine were compared to matched controls, statistically significant differences where found in sleep duration, daytime sleepiness, night awakenings, sleep anxiety, parasomnias, sleep onset delay, bedtime resistance, and sleep-disordered breathing [Miller et al., 2003]. It remains unclear, however, whether sleep disturbances increase the occurrence of migraine, whether frequent and intense migraine leads to sleep disturbances, or whether the two are unrelated. Current practice is to recommend good sleep hygiene.

Exercise is recommended for patients with frequent migraines, and a review of Internet websites serving headache sufferers reveals the common endorsement of regular physical activity. A recent study to evaluate the effects of exercise on plasma beta-endorphin levels in 40 migraine patients found beneficial effects on all migraine parameters [Koseoglu et al., 2003].

The role of dietary measures has recently been reviewed, yet the subject remains controversial [Millichap and Yee, 2003]. Between 7 and 44 percent of children and adults with migraine report that a particular food or drink can precipitate a migraine attack [Stang et al., 1992; Van den Bergh et al., 1987]. In children, the principal dietary triggers were cheese, chocolate, and citrus fruits. Other purported dietary precipitants included processed meats, yogurt, fried foods, monosodium glutamate, aspartamine, and alcoholic beverages. For chocolate, the median time interval to the onset of headache following ingestion was 22 hours (3.5–27 hours) [Gibb et al., 1991].

In addition to looking at what patients eat, it is important to encourage them to take regular meals and to drink plenty of fluids. Many teenagers routinely skip breakfast. Missing meals is a common precipitant of migraine and is identified by adolescents as one of the leading triggers [Lewis et al., 1996]. A simple lifestyle modification for adolescents with frequent migraine includes eating three meals a day, including breakfast, and to consume plenty of water.

Overuse of “over-the-counter” ANALGESICS has been a particular focus recently. Recognized in adults some years ago, overuse (more than 5 times per week) of acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and, to a lesser extent, aspirin-containing compounds can be a contributing factor to frequent, even daily, headache patterns. When recognized, patients who are overusing ANALGESICS must be educated to discontinue the practice. Retrospective studies have suggested that this recommendation alone can decrease headache frequency [Reimschisel, 2003; Rothner and Guo, 2004].

Caffeine in coffee and sodas warrants special mention. A link between caffeine and migraine has been established [James, 1998; Mannix et al., 1997]. Not only does caffeine itself seem to have an influence on headache; caffeine may disrupt sleep or aggravate mood, both of which may exacerbate headache. Furthermore, caffeine withdrawal headache, which begins 1–2 days following cessation of regular caffeine use, can last up to a week [Dusseldorp and Katan, 1990]. Every effort must be made to moderate caffeine use.

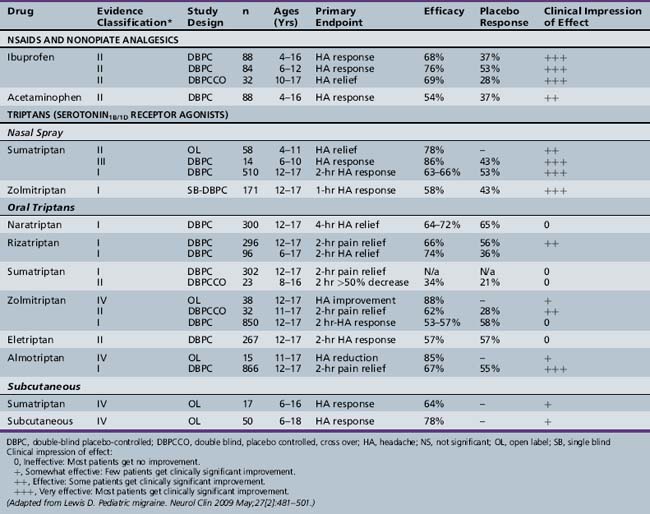

The pharmacologic management of pediatric migraine has been subjected to thorough review but controlled data are, unfortunately, limited (Table 63-2 and Table 63-3) [Lewis et al., 2004; Victor and Ryan, 2003].

Table 63-2 Acute Treatments for Migraine in Children and Adolescents

| Agent | Dose |

|---|---|

| ANALGESICS | |

| Ibuprofen | 7–10 mg/kg/ every 4–6 hours |

| Acetaminophen | 15 mg/kg/ every 4–6 hours |

| Naproxen sodium | 10–15 mg/kg every 8–12 hours |

| Ketorolac | 10–30 mg IV, PO |

| TRIPTANS | |

| Nasal Sprays | |

| Sumatriptan | 5–20 mg |

| Zolmitriptan | 5–10 mg |

| Oral Forms | |

| Almotriptan* | 6.25, 12.5 mg |

| Eletriptan | 20, 40 mg |

| Frovatriptan | 2.5 mg |

| Naratriptan | 1, 2.5 mg |

| Sumatriptan | 25, 50, 100 mg |

| Rizatriptan | 5, 10 mg (tablet and ODT) |

| Zolmitriptan | 5, 10 mg (tablet and ODT) |

| Injectable (Subcutaneous) | |

| Sumatriptan | 6 mg |

IV, intravenous; ODT, oral disintegrating tablet; PO, by mouth.

* Approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in adolescents 12–17 years with migraine  4 hours.

4 hours.

For the acute treatment of migraine, the most rigorously studied agents are ibuprofen, acetaminophen, and the “triptans” (almotriptan and rizatriptan tablets, sumatriptan and zolmitriptan nasal sprays), all of which have shown safety and efficacy in controlled trials. Almotriptan is the only triptan approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in adolescents. No triptan is approved for children under age 12. For children less than 12 years of age, ibuprofen (7.5–10 mg/kg) and acetaminophen (15 mg/kg) have demonstrated efficacy and safety in the acute treatment of migraine [Hamalainen et al., 1997; Lewis et al., 2002]. Almotriptan demonstrated statistically significant efficacy over placebo in adolescents aged 12–17 (n = 866), with 2-hour headache relief of 73 percent in the 12.5 mg almotriptan tablet group and 52 percent in the placebo group (p <0.01) [Linder et al., 2008]. Zolmitriptan (5 mg) and sumatriptan (5 and 20 mg) in the nasal spray form and rizatriptan (5 and 10 mg) have demonstrated both safety and efficacy in controlled trials in adolescents, but have not yet received FDA approval [Lewis et al., 2007; Winner et al., 2000; Ahonen et al., 2004, 2006; Ueberall, 2001]. Butalbital preparations are no longer recommended.

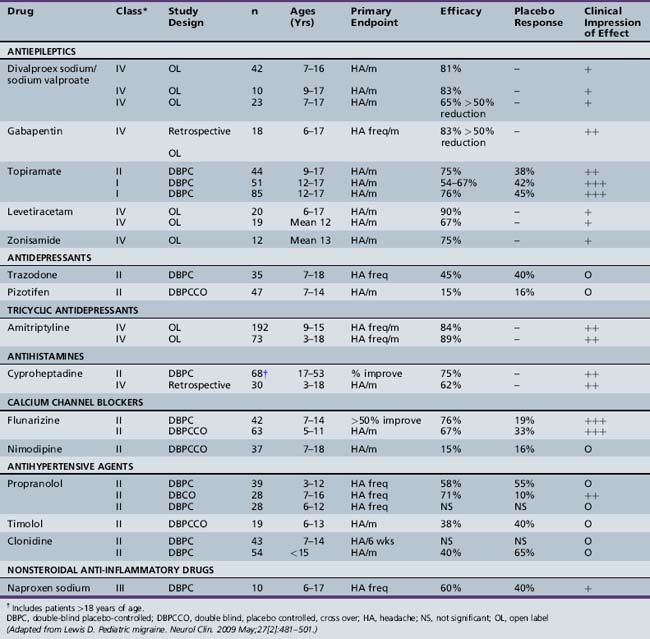

For preventative treatment in the population of children and adolescents with frequent, disabling migraine, topiramate and flunarizine (not available in the U.S.) have demonstrated efficacy in controlled trials (Table 63-4 and Table 63-5). In a recent controlled, blinded trial, topiramate (100 mg/day) resulted in a statistically significant reduction in the monthly migraine attack rate from baseline versus placebo (72.2 versus 44.4 percent). Furthermore, a 50 percent reduction in monthly migraine day rate from baseline versus placebo favored topiramate at 100 mg/day (83 versus 45 percent) [Lewis et al., 2009].

Table 63-4 Preventative Agents for Treatment of Migraine in Children and Adolescents

| Agent | Dose |

|---|---|

| ANTIDEPRESSANT AGENTS | |

| Amitriptyline | 5–25 mg at bedtime |

| ANTIEPILEPTIC AGENTS | |

| Topiramate | 15–25 mg hs titrate, up to 50 mg twice daily |

| Valproic acid | 250–500 mg orally twice daily |

| 500–1000 mg ER preparation at bedtime | |

| NONSTEROIDAL ANTI-INFLAMMATORY AGENTS | |

| Naproxen | 250–500 mg orally twice daily (maximum 6 weeks) |

| ANTIHYPERTENSIVE AGENTS | |

| Propranolol | 60–120 mg orally once a day |

| ANTIHISTAMINES | |

| Cyproheptadine | 2–8 mg orally divided tid, bid, or twice or three times daily |

ER, extended-release; hs, at bedtime.

Uncontrolled data are emerging regarding antiepileptic agents, such as disodium valproate and levetiracetam, as well as the antihistamine cyproheptadine and the antidepressant amitriptyline [Serdaroglu et al., 2002; Miller, 2004; Lewis et al., 2004].

Other Primary Headache Syndromes

Chronic Daily Headache

CDH is formally defined as spanning a period of more than 4 months, during which the patient has more than 15 headaches per month, with the headaches lasting more than 4 hours per day. Many adolescents will report having headaches virtually every single day, sometimes during every waking hour. This chronic, nonprogressive, unremitting, daily or near-daily pattern of headache represents one of the most difficult subsets of headache. The estimated prevalence of CDH in adolescents is about 1–2 percent, and may be as high as 4 percent in the adult population [Abu-Arefeh and Russell, 1994; Lipton and Stewart, 1997; Castillo et al., 1999]. CDH is very common in referral headache centers, where up to 15–20 percent of patients will present with daily or near-daily head pain [Viswanathan et al., 1998].

Four primary chronic headache categories have been identified:

Each of these four types of CDH is further separated into those with or without superimposed analgesic overuse (>5 doses/week of over-the-counter ANALGESICS). The medications implicated in this analgesic overuse syndrome include most over-the-counter ANALGESICS (e.g., acetaminophen, aspirin, ibuprofen), opioids, butalbital, isometheptene, benzodiazepines, ergotamine, and triptans [Mathew et al., 1990].

An integral part of the educational process will be the incorporation of wholesale lifestyle changes, such as regulation of sleep and eating habits, regular exercise, identification of triggering factors, stress management biofeedback-assisted relaxation therapy and biobehavioral programs, and psychological or psychiatric intervention (see Box 63-9) [Rothrock, 1999].

For the population of children and adolescents with CDH, preventative therapy takes center-stage and represents the mainstay of drug treatment (see Tables 63-3 and 63-4). Since the majority of children with CDH has chronic migraine or prominent migrainous features, a modification of standard migraine therapy is appropriate, but emphasis must be placed on prevention measures rather than analgesic or abortive strategies. The one exception may be the patients with a recent onset of CDH attributed almost exclusively to analgesic rebound. In this infrequent group, a trial of an analgesic-free period, as noted above, may be the sole successful treatment.

Preventative therapies used for CDH include tricyclic antidepressants, antiepileptic agents, beta-blockers, serotonergic agents, calcium channel blockers, and other miscellaneous treatments; however, none of these medications has been subjected to controlled trials and none is currently approved for the prevention of headaches in children [Redillas and Solomons, 2000].

Antidepressants

The tricyclic antidepressant, amitriptyline, has been widely used for the prevention of migraine headaches. The mechanism of action is unclear, but is thought to be due to a multiple reuptake inhibitor action. The agents are well tolerated in children and adolescents; side effects are attributable to their anticholinergic effects, and there are additional concerns about cardiac arrhythmias. The most frequently cited side effects include sedation. In order to minimize side effects, a slow taper, starting at 0.25 mg/kg (5–10 mg) and increasing by 5–10 mg every 2–3 weeks until a dose of 1.0 mg/kg (10–25 mg) is reached, results in well-tolerated, effective management [Hershey et al., 2000].

SSRIs have not been studied for CDH, but may have a role in those patients with comorbid depression.

Antiepileptic Drugs

Several antiepileptic drugs have been shown to be effective in preventing adult migraine; however, very limited evidence is available in children. Topiramate has demonstrated efficacy in preventing adult and adolescent migraine [Brandes et al., 2004]. A significant reduction in headache frequency was demonstrated at doses of 50–100 mg b.i.d. Adverse events resulting in discontinuation in the topiramate groups included cognitive blunting, paresthesias, fatigue, and nausea. One retrospective study assessing the efficacy of topiramate for pediatric headache included 41 evaluable patients. Topiramate at daily doses of 1.4 (± 0.74) mg/kg/day was used, and headache frequency was reduced from 16.5 (± 10) headaches/month to 11.6 (± 10) headaches/month (p <0.001). Mean headache severity, duration, and accompanying disability were also reduced. Side effects included cognitive changes (12.5 percent), weight loss (5.6 percent), and sensory symptoms (2.8 percent) [Hershey et al., 2002]. This study population consisted predominantly of children with very frequent migraine headaches approaching the spectrum of CDH, as defined by ≥15 headaches per month. The most common side effects observed included paresthesias, weight loss, and cognitive problems. The cognitive problems appear to decline with use, and can be minimized by very slow tapering and starting at a very low dose. This starting dose may be as low as 12.5 mg/day, and this may be slowly increased by 12.5–25 mg every 2 weeks to a dose of 50 mg. b.i.d. [Hershey et al., 2002]. The weight loss needs to be monitored, although, for the majority, it does not appear to be significant.

Sodium valproate has been shown to be effective and is approved for the prevention of migraines in adults [Mathew et al., 1995]. It has also been shown to be effective for CDH and is available in an extended-release formulation [Freitag et al., 2001, 2002]. A small study of 42 patients demonstrated that it was effective and well tolerated in 7–16-year-olds [Caruso et al., 2000]. Two of the side effects that may limit its use in adolescents include weight gain and the development of ovarian cysts.

Gabapentin has also been used for prevention of adult headaches. It appears to be well tolerated; however, its effectiveness in children and adolescents is unknown [Mathew et al., 2001].

Antihistamines

The antihistamine cyproheptadine has been widely used for the prevention of migraine headaches in young children, but it has not been studied in CDH [Bille et al., 1977]. It tends to be very well tolerated; its most significant side effects are sedation and weight gain, which specifically limits its tolerability in adolescents.

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Agents

Naproxen sodium was shown to be effective in adolescent migraine in one small (n = 10) trial using a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover design [Lewis et al., 1994]. Sixty percent of the patients experienced a greater than 60 percent reduction in headache frequency and severity with naproxen 250 mg twice a day, whereas only 40 percent responded favorably to placebo. No adverse effects were noted in this study. Naproxen should not be used for longer than 8 weeks because of potential gastrointestinal toxicity.

Botulinum toxin type A (Botox) by injection has been found to be effective in the treatment of headache disorders in adults. A recent study reported treatment of 12 adolescents (14–18 years) who had Botox injections for migraine and CDH. Six patients (all female) were in long-term treatment and received Botox every 3 months. Effectiveness was evaluated using pain scales and a standardized quality of life survey at baseline and prior to each treatment session. Each patient had 9–63 (average = 42) injections per treatment. All six long-term patients reported improvement in headache symptoms, with decreases on pain scales and an average of 33–75 percent improvement in quality of life. Two long-term patients had complete relief of headaches between injection series. Four patients had only one series of injections with “good results.” Two patients had no improvement and refused additional injections. Side effects were mild ptosis (n = 1), blurred vision (n = 1), and a hematoma at injection site with tingling in one arm lasting 24 hours (n = 1). These results warrant a controlled trial evaluation of Botox since it may be an effective option for certain adolescents with intractable migraine and CDH [Chan et al., 2009].

Nonpharmacologic Measures for CDH

A variety of vitamins (e.g., riboflavin 400 mg/day), minerals (e.g., magnesium 400 mg/day), and herbal remedies (e.g. butterbur, feverfew) have been attempted for prevention of headaches. Unfortunately, none of these remedies has been thoroughly evaluated in children with CDH, but may play a role, particularly in families where traditional pharmacologic approaches are considered unacceptable (see Box 63-9).

Biofeedback-assisted relaxation training has been shown to be an effective treatment for aborting and preventing recurrent headaches in a large number of studies in children. This technique is typically taught over a multisession analysis. It is also effective in a single session with tape provided for home practicing [Powers et al., 2001]. It does require a degree of motivation in the child, and it is difficult to assess effectiveness in isolation. However, it has low side-effect potential and may provide a benefit, including moderation of stress and sleep-onset difficulties.

Psychological or psychiatric interventions are quite valuable if emotional comorbidity has been demonstrated [Juant et al., 2000]. In addition, if “stress” has been implicated as a possible migraine trigger, psychological or psychiatric intervention, stress management, or self-hypnosis may be beneficial for CDH treatment and management. For many adolescents with CDH, cognitive behavioral therapies take center-stage in management.

Cranial Neuralgias

Ophthalmoplegic Migraine

Once classified as migraine, ophthalmoplegic migraine (OM) is now viewed as a cranial neuralgia, but oddly still called “migraine.” This is one of the most dramatic and clinically challenging headache syndromes and, fortunately, one of the least common. Available epidemiological data suggest an annual incidence of 0.7 per million [Hansen et al., 1990]. The two key features are ophthalmoparesis and headache, though the headache may be mild or a nondescript retro-orbital discomfort. Ptosis, adduction defects, and skew deviations are the common objective findings.

The oculomotor nerve, or its divisions, is most frequently involved, but pupillary involvement is inconsistent, with some authors reporting pupillary involvement in only one-third of patients [Vijayan, 1980]. The oculomotor nerve involvement may be incomplete, with partial deficits in both inferior and superior divisions of the third nerve. Abduction defects, due to abducens nerve involvement, constitute the second most frequently reported variant of OM, while trochlear nerve involvement is the least common.

The mechanism of OM is controversial. The primary theories suggest ischemic, compressive, or inflammatory processes [Stommel et al., 1994]. Lack of pupillary involvement argues for an ischemic mechanism, whereas a higher incidence of pupillary involvement weighs toward a compressive mechanism. Alternatively, recent reports have questioned whether OM may be an inflammatory process within the spectrum of Tolosa–Hunt syndrome, particularly given the steroid-responsiveness of many patients. Furthermore, high-resolution neuroimaging has shown a reversible enhancement of the oculomotor nerve during attacks, which lends further credence to an inflammatory/demyelinating mechanism, validating the ICHD-2 classification as a cranial neuropathy [Mark et al., 1998].

Cluster Headache

The trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias (TACs) represent a group of primary headache disorders associated with excruciating head pain, accompanied by autonomic features such as lacrimation, ptosis, rhinorrhea, and vasomotor changes. Cluster headache is an uncommon TAC in children and adolescents. The prevalence of childhood onset of cluster headache is approximately 0.1 percent [Lampl, 2002]. The diagnostic criteria require at least five attacks of severe unilateral orbital pain lasting 15–180 minutes, with a sense of restless agitation accompanied by ipsilateral conjunctival injection, lacrimation, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, eyelid edema, forehead sweating, miosis, or ptosis. Cluster headaches may be episodic or chronic, and attacks occur in series that last for weeks or even months. A cluster may be precipitated by alcohol, histamine, or nitroglycerine. Males are three times more likely to be affected than females.

The management is difficult. Acute treatments include inhalation of 100 percent oxygen at 8–10 L/min for 10–15 minutes through a non-rebreathing facemask; sumatriptan 6 mg subcutaneous injections or 20 mg intranasally, zolmitriptan nasal spray 5–10 mg; and intravenous, intramuscular, or subcutaneous injections of dihydroergotamine, 0.5–1.0 mg, at headache onset. Prophylactic medications useful in preventing attacks during cluster cycles include verapamil, sodium valproate, topiramate, melatonin, lithium carbonate, methysergide, and ergotamine tartrate [Newman et al., 2001; Rosen, 2009].

Specific Secondary Headache Syndromes

Post-Traumatic Headache

Chronic post-traumatic headache may be part of a global postconcussive syndrome, with behavioral changes (e.g., hyperactivity, hypoactivity), dizziness, tinnitus, vertigo, blurred vision, memory changes, sleep disorder, irritability, and attentional disorders. The duration of symptoms is variable, with some patients having brief, self-limited syndromes, and others suffering from headaches for more than 6–12 months. One retrospective study of 23 children with chronic post-traumatic headache found a mean duration of 13.3 months (range 2–60 months, median 7 months) [Callaghan, 2001]. The headache forms span the spectrum from tension-type, migraine, CDH, neuralgias (e.g., occipital neuralgia), temporomandibular joint dysfunction, and even, on rare occasions, cluster headache.

A recent prospective study of 117 children (81 males, 36 females; range 3–15 years [mean age 8.5 yrs]) admitted with closed head injury (minor 79 percent, major 21 percent) found that 8 (7 percent) children (5 males, 3 females; mean age 10.5 yrs) reported chronic post-traumatic headache. Five (4 percent) children had episodic tension-type headache and 3 (2.5 percent) had migraine with or without aura. Headache resolved over 3–27 months in all patients [Kirk et al., 2008].

Many athletes competing in contact sports experience post-traumatic headache as part of a postconcussion syndrome. A common question concerns when it is safe to return to full contact. Three organizations – the AAN, the American College of Sports Medicine, and the British Association of Sport and Exercise Medicine – have provided guidelines regarding return to activities, which range from 1 to 4 weeks [Quality Standards Subcommittee, 1997; American College of Sports Medicine, 1991; McCrory et al., 2009]. These guidelines are available online. See http://aappolicy.aapublications.org/cgi/content/full/pediatrics and http://www.acsm.org.

Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension

The diagnostic criteria for IIH in the prepubertal child include normal mental status; symptoms and signs of generalized intracranial hypertension (e.g., papilledema); documented elevated intracranial pressure measured in the lateral decubitus position (<8 years, 180 mm H2O; ≥ 8 years, 250 mm H2O); normal CSF composition; absence of evidence of hydrocephalus; mass, structural, or vascular lesion on neuroimaging (narrowing of the transverse sinuses is allowed); and no other identified cause of intracranial hypertension [Rangwala and Liu, 2007]. The diagnostic test of choice for IIH is lumbar puncture, with measurement of opening pressure. Given a normal CT scan, the test can be accomplished safely, even though the examination shows a sixth nerve palsy, since this can be a “false localizing” sign, indicative of diffuse increase in intracranial pressure.

Brain Tumor Headache

About two-thirds of children with brain tumors will have headache as a presenting symptom. There is, however, no invariable “brain tumor headache” profile. A steady, gradual rise in intracranial pressure typically produces the chronic progressive pattern, but, on occasion, an anaplastic tumor or hemorrhage into tumor may cause an acute pattern (see Figure 63-1). Several historic clues suggest space-occupying lesions, such as brain tumors, but may also be present in other expanding masses, such as brain abscess, hematoma, or vascular anomaly. Morning headache or headaches that awaken the child from sleep are classic symptoms of the dependent edema of intracranial lesions. Likewise, nocturnal or morning emesis, with or without headache, suggests increased intracranial pressure and is a particularly common symptom of tumors arising near the floor of the fourth ventricle. Head pain aggravated by exertion or the Valsalva maneuver suggests a mass lesion. In addition to headache, parents may note behavioral or mood changes, cognitive changes, or declining school performance.

The key physical examination signs that indicate brain tumor include:

Chiari Malformation

Chiari malformations (type I) are, arguably, among the most common incidental findings when performing MRI in children with headache, and are the source of great controversy. Tonsillar ectopia of 5 mm or less is not considered pathological. When symptomatic, children with Chiari I malformation may complain of occipital headache, neck pain or stiffness, arm weakness, and gait abnormalities. The headache may be aggravated by neck flexion or extension, or the Valsalva maneuver. Basal skull abnormalities or scoliosis may be identified. In a retrospective MRI analysis of 49 children with Chiari I malformation, 57 percent of children were asymptomatic. Headache and neck pain were the most frequent complaints. Syringomyelia was detected in 14 percent of patients and skull-base abnormalities in 50 percent. The magnitude of tonsillar ectopia (5–23 mm) correlated with severity score (p = 0.04), but not with other clinical measures. Children with greater amounts of tonsillar ectopia on MRI are more likely to be symptomatic [Wu et al., 1999]. Extreme care must be exercised before embarking upon surgical decompression. MRI with CSF flow studies may help to determine whether suboccipital decompression is necessary.

Metabolic Causes of Headache in Children

MELAS

Mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes (MELAS) constitute a mitochondrial disorder characterized by migraine-like headaches, episodic hemiparesis, development regression/dementia, short stature, seizures, and cortical blindness. The initial presentation is seizures in 28 percent, recurrent headache in 28 percent, gastrointestinal symptoms (emesis or anorexia) in 25 percent, limb weakness in 18 percent, short stature in 18 percent, and stroke in 17 percent. Onset age is below 2 years in 8 percent, 2–5 years in 20 percent, 6–10 years in 31 percent, 11–20 years in 17 percent, 21–40 years in 23 percent, and over age 40 in only 1 percent [DiMauro and Hirano, 2005].

CADASIL

Cerebral autosomal-dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) is a mitochondrial disorder that usually affects young adults, but can rarely be seen in adolescents. It should be considered in adolescents with migraine with aura, in whom neuroimaging discloses subcortical infarcts and/or multifocal T2/fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) hyperintensities in the deep white matter. An autosomal-dominant family history of migraine, early stroke, and/or dementia may be present. The clinical spectrum is variable, but migraine headache occurs in more than one-third of patients and may be the only manifestation. A recent case report described a 14-year-old girl with a 3-year history of episodic headaches, three episodes of right hemiparesis, persistent hypertension, negative family history, normal MRI, and a “Notch3” mutation [Golomb et al., 2004]. This case report raises the possibility of screening for CADASIL in children with headaches and hemiplegia episodes (hemiplegic migraine) using skin biopsy and genetic testing for the Notch3 mutation, even when MRI is normal and family history negative.

References

![]() The complete list of references for this chapter is available online at www.expertconsult.com.

The complete list of references for this chapter is available online at www.expertconsult.com.

Abu-Arefeh I., Russell G. Prevalence of headache and migraine in schoolchildren. Br Med J. 1994;309:765-769.

Ahonen K., Hämäläinen M.L., Eerola M., et al. A randomized trial of rizatriptan in migraine attacks in children. Neurology. 2006;67(7):1135-1140. Epub 2006 Aug 30

Ahonen K., Hamalainen M.L., Rantala H., et al. Nasal sumatriptan is effective in the treatment of migraine attacks in children. Neurology. 2004;62:883-887.

Aicardi J., Bourgeois M., Goutieres F. Alternating hemiplegia of childhood: clinical findings and diagnostic criteria. In: Andermann F., Aicardi J., Vigevano F., editors. Alternating Hemiplegia of Childhood. New York: Raven Press; 1995:3-18.

American College of Emergency Physicians. Clinical policy for the initial approach to adolescents and adults presenting to the emergency department with a chief complaint of headache. Ann of Emerg Med. 1996;27:821-844.

American College of Sports Medicine. Guidelines for the Management of Concussion in Sports, Rev. ed. Denver, CO: Denver, Colorado Medical Society; 1991.

Amit R. Acute confusional state in childhood. Childs Nerv Syst. 1988;4:255-258.

Barlow C.F. Headaches and Migraine in Childhood. Clin Dev Med. 1984;91:93-103.

Bassi T., Bresolin N., Tonelli A., et al. A novel mutation in the ATP1A2 gene causes alternating hemiplegia of childhood. J Med Genet. 2004;41:621-628.

Baumann R.J. Behavioral treatment of migraine in children and adolescents. Paediatr Drugs. 2002;4(9):555-561.

Bickerstaff E.R. Basilar artery migraine. Lancet. 1961;1:15-17.

Bille B. Migraine in school children. Acta Paediatr. 1962;51(Suppl 136):1-151.

Bille B., Ludvigsson J., Sanner G. Prophylaxis of migraine in children. Headache. 1977;17:61-63.

Brandes J.L., Saper J.R., Diamond M., et al. Topiramate for migraine prevention: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:965-973.

Burstein R., Collins B., Jakubowski M. Defeating migraine pain with Triptans: A race against the development of cutaneous allodynia. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:19-26.

Burstein R., Jakubowski M. Analgesic Triptan Action in an Animal Model of Intracranial Pain: A race against the development of central sensitization. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:27-36.

Burstein R., Yarnitsky D., Goor-Aryeh I., et al. An association between migraine and cutaneous allodynia. Ann Neurol. 2000;47:614-624.

Callaghan M. Chronic posttraumatic headache in children and adolescents. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001;43:819-822.

Caruso J., Brown W., Exil G., et al. The efficacy of divalproex sodium in the prophylactic treatment of children with migraine. Headache. 2000;40:672-676.

Castillo J., Munoz P., Guitera V., et al. Epidemiology of chronic daily headache in the general population. Headache. 1999;39:190-196.

Chan V.W., McCabe E.J., MacGregor D.L. Botox treatment for migraine and chronic daily headache in adolescents. J Neurosci Nurs. 2009;41:235-243.

Chaves-Carballo E. Paroxysmal Torticollis. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 1996;3:255-256.

Chutorian A.M. Benign paroxysmal torticollis, tortipelvis and retrocollis of infancy. Neurology. 1974;24:366-367.

Dalsgaard-Nielsen T. Some aspects of the epidemiology of migraine in Denmark. Headache. 1970;10:14-23.

Deubner D.C. An epidemiologic study of migraine and headache in 10-20 year olds. Headache. 1977;17:173-180.

Dichgans M., Freilinger T., Eckstein G., et al. Mutation in the neuronal voltage-gated sodium channel SCN1A in familial hemiplegic migraine. Lancet. 2005;366:371-377.

DiMauro S., Hirano M., MELAS. GeneTests. 2005.

Dusseldorp M., Katan M. Headache caused by caffeine withdrawal among moderate coffee drinkers switched from ordinary to decaffeinated coffee: a 12 week double-blind trial. BMJ. 1990;300:1558-1559.

Ehyai A., Fenichel G. The natural history of acute confusional migraine. Arch Neurol. 1978;35:368-369.

Ferrera P.C., Reicho P.R. Acute confusional migraine and trauma-triggered migraine. Am J Emerg Med. 1996;14:276-278.

Freitag F., Collins S., Carlson H., et al. A randomized trial of divalproex sodium extended-release tablets in migraine prophylaxis. Neurology. 2002;58:1652-1659.

Freitag F., Diamond S., Diamond M., et al. Divalproex in the long-term treatment of chronic daily headache. Headache. 2001;41:271-278.

Garcon G., Barlow C.F. Juvenile migraine presenting as acute confusional states. Pediatrics. 1970;45:628-635.

Gardner K., Barmada M.M., Ptacek L.J., et al. A new locus for hemiplegic migraine maps to chromosome 1q31. Neurology. 1997;49:1231-1238.

Gibb C., Davies P., Glover V., et al. Chocolate is a migraine-provoking agent. Cephalalgia. 1991;11:93-95.

Giffin N.J., Benton S., Goadsby P.J. Benign paroxysmal torticollis of infancy: four new cases and linkage to CACNA1A mutation. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2002;44:490-493.

Gladstein J., Holden E., Winner P., et al. Chronic daily headache in children and adolescents: Current status and recommendations for the future. Headache. 1997;37:626-629.

Goadsby P.J., Charbit A.R., Andreou A.P., et al. Neurobiology of migraine. Neuroscience. 2009;161:327-341.

Golden G.S., French J.H. Basilar artery migraine in young children. Pediatrics. 1975;56:722-726.

Golomb M.R., Sokol D.K., Walsh L.E., et al. Recurrent hemiplegia, normal MRI, and NOTCH3 mutation in a 14-year-old: is this early CADASIL? Neurology. 2004;62(12):2331-2332.

Hachinshi V.C., Porchawka J., Steele J.C. Visual symptoms in the migraine syndrome. Neurol. 1973;23:570-579.

Hamalainen M.L., Hoppu K., Valkeila E., et al. Ibuprofen or acetaminophen for the acute treatment of migraine in children: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Neurology. 1997;48:102-107.

Hansen S.L., Borelli-Moller L., Strange P., et al. Ophthalmoplegic migraine: diagnostic criteria, incidence of hospitalization, and possible etiology. Acta Neurol Scand. 1990;81:54-60.

Hershey A., Powers S., Bentti A., et al. Effectiveness of amitriptyline in the prophylactic management of childhood headaches. Headache. 2000;40:539-549.

Hershey A.D., Powers S.W., Vockell A.L., et al. Effectiveness of topiramate in the prevention of childhood headache. Headache. 2002;42:810-818.

Holroyd K., Mauskop A. Complementary and alternative treatments. Neurology. 2003;60(Suppl 2):58-62.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bookshelf/br.fcgi?book=gene&part=fhm.

James J.E. Acute and chronic effects of caffeine on performance, mood, headache, and sleep. Neuropsychobiology. 1998;38:32-41.

Jensen T.S. Transient global amnesia in childhood. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1980;22(5):654-658.

Joutel A., Bousser M.-G., Biousse V., et al. A gene for familial hemiplegic migraine maps to chromosome 19. Nat Genet. 1993;5:40-45.

Juant K., Wang S., Fuh J., et al. Comorbidity of depressive and anxiety disorders in chronic daily headache and its subtypes. Headache. 2000;40:818-823.

Kirk C., Nagiub G., Abu-Arafeh I. Chronic post-traumatic headache after head injury in children and adolescents. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50:422-425.

Koseoglu E., Akboyraz A., Soyuer A., et al. Aerobic exercise and plasma beta endorphin levels in patients with migrainous headache without aura. Cephalalgia. 2003;23(10):972-976.

Lampl C. Childhood-onset cluster headache. Pediatr Neurol. 2002;27:138-140.

Lapkin M.L., Golden G.S. Basilar artery migraine, a review of 30 cases. Am J of Dis of Child. 1978;132:278-281.

La Spina I., et al. Basilar artery migraine: transcranial Doppler EEG and SPECT from the aura phase to the end. Headache. 1997;37:43-47.

Laurell K., Larsson B., Eeg-Olofsson O. Prevalence of headache in Swedish schoolchildren, with a focus on tension-type headache. Cephalalgia. 2004;24:380-388.

Laurell K., Larsson B., Eeg-Olofsson O. Prevalence of headache in Swedish schoolchildren, with a focus on tension-type headache. Cephalalgia. 2004;24:380-388.

Lewis D., Ashwal S., Hershey A., et al. Practice Parameter: Pharmacologic Treatment of migraine headache in children and adolescents. Neurology. 2004;63(12):2215-2224. Dec 28

Lewis D., Diamond S., Scott D., et al. Prophylactic treatment of pediatric migraine. Headache. 2004;44:230-237.

Lewis D., Winner P., Saper J., et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of topiramate for migraine prevention in pediatric subjects 12 to 17 years of age. Pediatrics. 2009;123(3):924-934.

Lewis D.W. Migraine and migraine variant in childhood and adolescence. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 1995;2:127-143.

Lewis D.W., Ashwal S., Dahl G., et al. Practice Parameter: Evaluation of children and adolescents with recurrent headache. Neurology. 2002;59:490-498.

Lewis D.W., Kellstein D., Burke B., et al. Children’s Ibuprofen Suspension for the Acute Treatment of Pediatric Migraine Headache. Headache. 2002;42(8):780-786.

Lewis D.W., Middlebrook M.T., Deline C. Naproxen Sodium for Chemoprophylaxis of Adolescent Migraine. Ann Neurol. 1994;36:542.

Lewis D.W., Middlebrook M.T., Mehallick L., et al. Pediatric Headaches: What do the children want? Headache. 1996;36:224-230.

Lewis D.W., Winner P., Hershey A.D., et al. Efficacy of zolmitriptan nasal spray in adolescent migraine. Pediatrics. 2007;120:390-396.

Li B.U., Lefevre F., Chelimsky G.G., et al. North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of cyclic vomiting syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47(3):379-393.

Linder S.L., Mathew N.T., Cady R.K., et al. Efficacy and tolerability of almotriptan in adolescents: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Headache. 2008;48(9):1326-1336. Epub 2008 May 14

Lipton R., Stewart W. Prevalence and impact of migraine. Neurol Clin. 1997;15:1-13.

Lipton R.B., Silberstein S.D., Stewart W.F. An update on the epidemiology of migraine. Headache. 1994;34:319-328.

Mannix L.K., Frame J.R., Soloman G.D. Alcohol, smoking and caffeine use among headache patients. Headache. 1997;37:572-576.

Mark A.S., et al. Ophthalmoplegic migraine: reversible enhancement and thickening of the cisternal segment of the oculomotor nerve on contrast-enhanced MR images. Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19:1887-1891.

Mathew N., Rapoport A., Saper J., et al. Efficacy of gabapentin in migraine prophylaxis. Headache. 2001;41:119-128.

Mathew N., Saper J., Siberstein S., et al. Migraine Prophylaxis With Divalproex. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:281-286.

Mathew N.T., Kurman R., Perez F. Drug-induced refractory headache – clinical features and management. Headache. 1990;30:634-638.

McCrory P., Meeuwisse W., Johnston K., et al. Consensus Statement on Concussion in Sport; the 3rd International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Zurich Nov 2008. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(Suppl 1):i76-i84.

Miller G.S. Efficacy and safety of levetiracetam in pediatric migraine. Headache. 2004;44:238-243.

Miller V., Palermao T., Powers S., et al. Migraine Headaches and Sleep Distrurbances in Children. Headache. 2003;43:362-368.

Millichap J., Yee M. The diet factor in pediatric and adolescent migraine. Pediatr Neurol. 2003;28:9-15.

Mortimer M.J., Kay J., Jaron A. Epidemiology of Headache and Childhood Migraine in an Urban General Practice Using Ad Hoc, Vahlquist and IHS Criteria. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1992;34:1095-1101.

Newman L., Goadsby P., Lipton R. Cluster and related headaches. Med Clin North Am. 2001;85:997-1016.

Oleson J. The international classification of headache disorders. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(Suppl 1):1-160.

Olness K., MacDonald J.T., Uden D.L. Comparison of Self-Hypnosis and Propranolol in the Treatment of Juvenile Classic Migraine. Pediatrics. 1987;79:593-597.

Ophoff R.A., Terwindt G.M., Vergouwe M.N., et al. Involvement of a Ca2+ Channel Gene in Familial Hemiplegic Migraine and Migraine with and without Aura. Headache. 1997;37:479-485.

Pietrobon D., Striessnig J. Neurobiology of Migraine. Nat Rev. 2003;4:386-398.

Powers S., Mitchell M., Byars K., et al. Effectiveness of one-session biofeedback training in a pediatric headache center: a pilot study. Neurology. 2001;56:133.

Powers S., Patton S., Hommel K., et al. Quality of life in childhood migraine: clinical aspects and comparison to other chronic illness. Pediatrics. 2003;112:e1-e5.

Powers S., Patton S., Hommell K., et al. Quality of life in paediatric migraine: characterization of age-related effects using PedsQL 4.0. Cephalalgia. 2004;24:120-127.

Quality Standards Subcommittee, American Academy of Neurology. Practice parameter. The management of concussions in sports. Neurology. 1997;48:581-585.

Rangwala L.M., Liu G.T. Pediatric idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52(6):597-617.

Redillas C., Solomons S. Prophylactic pharmacological treatment of chronic daily headache. Headache. 2000;40:83-102.

Reimschisel T. Breaking the cycle of medication overuse headache. Contemp Pediatr. 2003;20:101.

Rho J.M., Chugani H.T. Alternating Hemiplegia of Childhood: Insights into its pathogenesis. J Child Neurol. 1998;13:39-45.

Rosen T. Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias. Neurol Clin North Am. 2009;27:537-556.

Rosman N.P., Douglass L.M., Sharif U.M., et al. The neurology of benign paroxysmal torticollis of infancy: report of 10 new cases and review of the literature. J Child Neurol. 2009;24:155-160.

Rothner A., Guo Y. An analysis of headache types, over-the-counter (OTC) medication overuse and school absences in a pediatric/adolescent headache clinic. Headache. 2004;44:490.

Rothner A.D. The evaluation of Headaches in Children and Adolescents. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 1995;2:109-118.

Rothrock J. Management of chronic daily headache utilizing a uniform treatment pathway. Headache. 1999;39:650-653.

Serdaroglu G., Erhan E., Tekgul, et al. Sodium valproate prophylaxis in childhood migraine. Headache. 2002;42:819-822.

Silberstein S. Migraine. Lancet. 2004;31:381-391.

Silberstein S.D. Practice Parameter: Evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review). Neurology. 2000;55:754-762.

Sillanpaa M. Prevalence of migraine and other headache in Finnish children starting school. Headache. 1976;15:288-290.

Sillanpaa M. Changes in the prevalence of migraine and other headache during the first seven school years. Headache. 1983;23:15-19.

Small P., Waters W.E. Headache and migraine in a comprehensive school. In: Waters, editor. The Epidemiology of Migraine. Bracknell-Berkshire, England: Boehringer Ingel-helm, Ltd; 1974:56-67.

Snyder C.H. Paroxysmal torticollis in infancy. A possible form of labyrinthitis. Am J Dis Child. 1969;117:458-460.

Stang P., Yanagihar P., Swanson J., et al. Incidence of migraine headache: A population based study in Olmsted County, Minn. Neurology. 1992;42:1657-1662.

Stewart W.F., Linet M.S., Celentano D.D., et al. Age and sex-specific incidence rates of migraine with and without visual aura. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;34:1111-1120.

Stewart W.F., Lipton R.B., Celentano D.D., et al. Prevalence of migraine headache in the United States. JAMA. 1992;267:64-69.

Stommel E.W., et al. Ophthalmoplegic migraine or Tolosa-Hunt syndrome? Headache. 1994;34:177.

Sweney M.T., Silver K., Gerard-Blanluet M., et al. Alternating hemiplegia of childhood: early characteristics and evolution of a neurodevelopmental syndrome. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e534-e541.

Swoboda K.J., Kanavakis E., Xaidara A., et al. Alternating hemiplegia of childhood or familial hemiplegic migraine? A novel ATP1A2 mutation. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:884-887.

The Childhood Brain Tumor Consortium. The epidemiology of headache among children with brain tumor. Headache in children with brain tumors. J Neurooncol. 1991;10:31-46.

Ueberall M. Sumatriptan in paediatric and adolescent migraine. Cephalalgia. 2001;21(Suppl 1):21024.

Valquist B. Migraine in children. Int Arch Allergy. 1955;7:348-355.

Van den Bergh V., Amery W., Waelkens J. Trigger factors in migraine: A study conducted by the Belgian Migraine Society. Headache. 1987;27:191-196.

Verret S., Steele J.C. Alternating hemiplegia in childhood: A report of eight patients with complicated migraine beginning in infancy. Pediatrics. 1971;47:675-680.

Victor S., Ryan S. Drugs for preventing migraine headaches in children. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 4, 2003. CD 002761

Vijayan N. Ophthalmoplegic Migraine: Ischemic or Compressive Neuropathy? Headache. 1980;20:300-304.

Viswanathan V., Bridges S.J., Whitehouse W., et al. Childhood headaches: discrete entities or continuum? Dev Med Child Neurol. 1998;40:544-550.

Wang S.J., Fuh J.L., Juang K.D. Chronic Daily Headache in adolescents; prevalence, impact, and medication overuse. Neurology. 2006;66:193-197.

Wang S.J., Fuh J.L., Lu S.R. Chronic Daily Headache in adolescents; an 8-year follow-up study. Neurology. 2009;73:416-422.

Winner P., Rothner A.D., Saper J., et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of sumatriptan nasal spray in the treatment of acute migraine in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2000;106:989-997.

Wu Y.W., Chin C.T., Chan M.D., et al. Pediatric Chiari I malformations. Do clinical and radiologic features correlate? Neurology. 1999;72:1271-1276.

Zwart J.A., Dyb G., Holmen T.L., et al. The prevalence of migraine and tension-type headaches among adolescents in Norway. The Nord-Trondelag Health Study (Head-HUNT-Youth), a large population-based epidemiological study. Cephalalgia. 2004;24:373-379.