23

Gynaecological surgery

Introduction

The decision to proceed to surgery is one that must be taken with care and responsibility, as life-threatening complications, though rare, can arise after even the most minor of operations. It is therefore essential that the patient has been adequately prepared for the operation, and that consent has been obtained by someone capable of weighing up the risks and the benefits. Careful preoperative counselling will enhance the patient’s experience and, along with good communication, adequate surgical time and continuity of care, maximize the chance of a successful outcome. This chapter will address the issues surrounding good surgical practice in patients undergoing gynaecological procedures.

Preoperative counselling

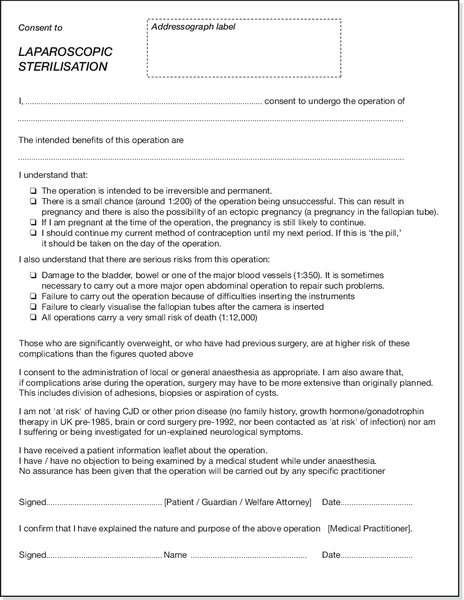

This is usually carried out in an outpatient clinic. The clinical need for surgery may be clear at the outset, but this must be communicated clearly with the patient with adequate time given to ask questions and obtain informed consent. It is good practice to give written information about the intended procedure, as well as contact details to allow the patient to revisit any uncertainties. Ideally, consent forms should be typed for clarity, and should be completed in the clinic and updated on the day of admission. An example of a consent form is shown in Figure 23.1. In the situation where the adult patient’s ability to consent is compromised (e.g. if they have dementia), it is good practice to involve the patient’s family or next of kin; how consent is formally obtained in this situation, will depend on the legal requirements of that country.

Risk can be a difficult concept to communicate with a patient, and sensitivity is required to balance a discussion of the serious nature of adverse outcomes in a manner that will not detract from the patient’s confidence in their doctor’s abilities. Trust is the cornerstone of the partnership between doctor and patient, and erosion of this at an early stage, will increase the likelihood of longer-term dissatisfaction.

The gynaecologist needs to consider comorbidities of any patient being considered for surgery and general anaesthesia. Are there less invasive and safer alternatives? Examples may include, ring pessaries instead of pelvic floor surgery for prolapse; levo-norgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) instead of hysterectomy for heavy menstrual bleeding; medical therapy for endometriosis; and implant, vasectomy or LNG-IUS instead of laparoscopic tubal ligation.

If surgery is to proceed, comorbidities should be communicated to the anaesthetist to allow satisfactory preparation and to avoid anaesthetic complications. Liaison with other specialties may be helpful to make the postoperative course run smoothly and clear management plans put in place, e.g. with haematology in patients requiring anticoagulation.

Common gynaecological operations

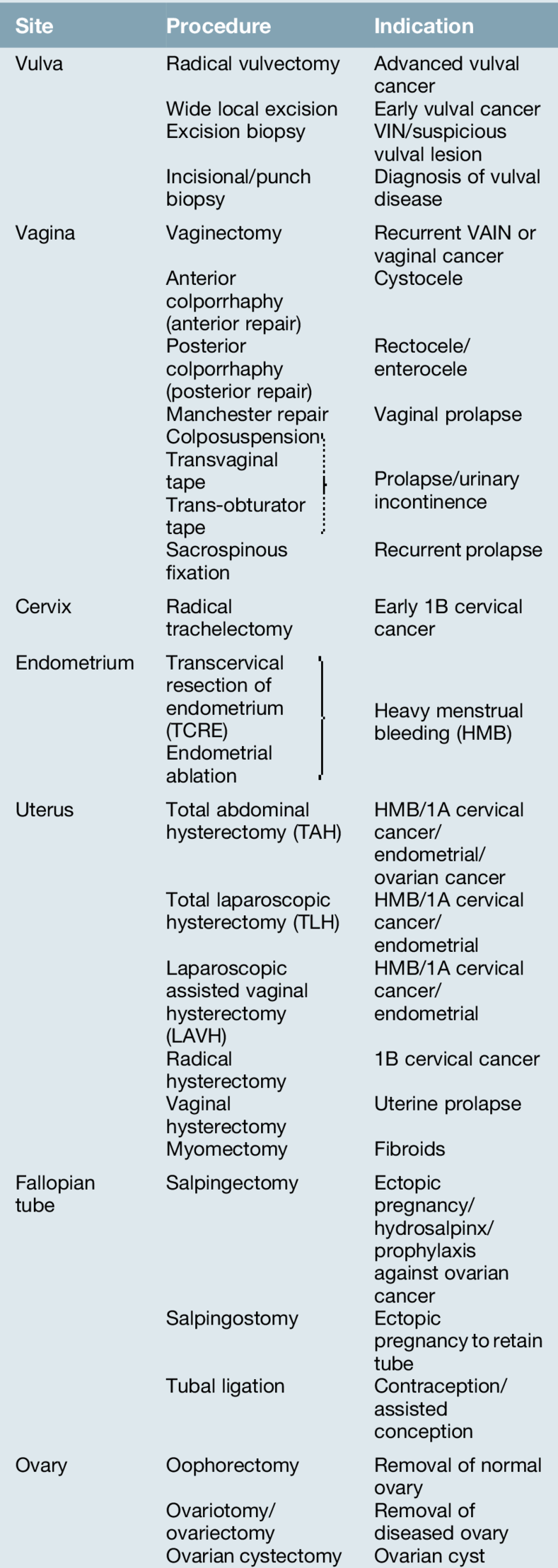

Gynaecological surgery generally involves removal or repair of the tissues of the female genital tract. In oncological surgery, this will also extend to removal of sites where gynaecological cancer may have spread, for example draining lymph nodes and omentum. Many of the procedures will be discussed in other chapters and therefore, only an overview will be given here. More common gynaecological procedures are listed in Table 23.1.

Surgical anatomy

Normal anatomy is shown in Figure 1.11. Recognition of structures at surgery can be quite different from this view, however, as underlying disease processes may disrupt normal anatomy by destroying normal tissue planes (e.g. in endometriosis and malignancy), and make identification of anatomical structures tricky for even the experienced surgeon.

Hysterectomy is one operation where the main gynaecological structures are often clearly visible and the principal steps in this procedure will be outlined below. Dissection usually involves a combination of scalpel, scissors and diathermy, but there is increasing use of sealing/cutting devices generated by high frequency oscillation of the instrument’s blade (Harmonic Ace, Ethicon) or bipolar diathermy (Ligasure, Covidien).

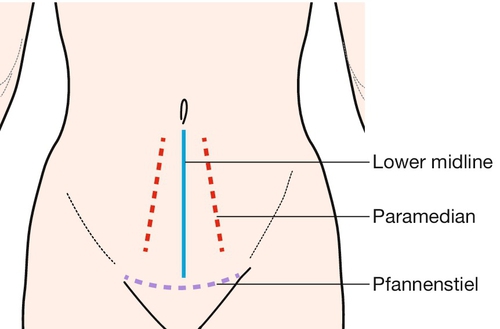

Skin incision

Options for type of skin incision are as shown in Figure 23.2. The most commonly used approach is the low transverse or Pfannenstiel incision. This is often preferred for cosmetic reasons, as the incision follows the natural skin crease (Langer’s lines), hence the alternative term ‘bikini-line incision’. The incision has the disadvantage of being more vascular than a midline incision and, if extended too laterally, can be associated with nerve damage. It also offers only a limited access to the pelvis and a midline or paramedian is preferred is there is a large pelvic mass such as a large ovarian cyst or fibroid uterus. However, it has a low incidence of wound herniation after repair due to the criss-crossing nature of vertical rectus abdominus muscles and the horizontal fibres of the rectus sheath. Once through the skin and subcutaneous layers of Camper’s and Scarpa’s fascia, the shiny white rectus sheath is revealed. This is then opened with a transverse incision and the rectus abdominus muscle lies beneath. The bellies of this muscle are separated in the midline and the extraperitoneal fat displaced to reveal the peritoneum. This is elevated between two clamps and carefully inspected to ensure no bowel lies below before entry. Care must be taken to identify the inferior epigastric vessels, which can bleed profusely if injured.

Round and infundibulo–pelvic ligaments

Following inspection of the pelvis, the bowel is packed away and a self-retaining retractor inserted. The uterus is held between two straight forceps and elevated. This delineates the round ligaments, which are then divided. The soft areolar tissue of the broad ligament, which lies between the anterior and posterior leaves of peritoneum, can be carefully dissected to reveal the ureter and ensure it is clear of the clamps to be placed on the ovarian vessels running in the infundibulo–pelvic ligament. This is the most common site for inadvertent ureteric injury. When the ovaries are to be conserved the clamp is simply placed on the medial side of the tubo-ovarian complex and the pedicle divided here instead. With increasing evidence of the tube being the source of high-grade serous cancers of the ovary and peritoneum, it is not unreasonable to remove the tubes but retain the ovaries in patients wishing to avoid castration.

Bladder reflection

The uterus is pulled cranially to help identify the utero-vesical peritoneum. The peritoneum is then divided and the areolar tissue around the bladder divided allowing the plane between bladder and anterior uterus and cervix to be developed. This displaces the bladder downwards, reducing the risk of damage later in the dissection or during repair of the vagina.

Division of the uterine vessels

The uterine artery is readily identifiable due to its spiral and tortuous appearance, a necessary feature for its rapid lengthening during pregnancy. The vaginal angles are then divided but the vagina not opened.

Opening the vagina

A knife is used to enter the anterior fornix and when the incision is widened the uterosacral ligaments are clamped and the remaining vaginal tissue divided to permit removal of the uterus from the pelvis.

The vaginal skin edges are grasped and the vaginal cuff oversewn either circumferentially or opposed to either side. It is not necessary to close the peritoneum, which will rapidly heal whether sutured or not.

Wound closure

Following closure of the vagina and achieving haemostasis, the tissues of the abdomen are closed in the reverse order to opening. It is important to appose the tissues and avoid over-enthusiastic tension in the sutures, as this will have a detrimental effect on tissue perfusion and increase likelihood of wound dehiscence.

Radical (Wertheim) hysterectomy for cervical malignancy differs from the simple hysterectomy by formally dissecting the ureter along its length in the pelvis, dividing the uterine vessels at their source as they leave the internal iliac vessels, thus allowing adequate dissection of the parametrial tissues, and cuff of vagina, to achieve adequate margins from the tumour.

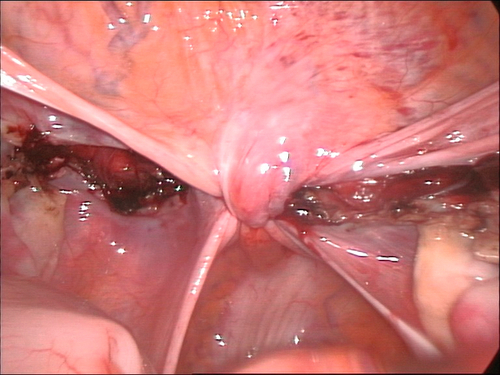

Laparoscopic surgery

Nearly all gynaecological operations that are carried out through an open incision can technically be undertaken with laparoscopic surgery. Although gynaecologists have been performing simple laparoscopic surgery for decades, the range of operations is now developing rapidly. There are constant improvements in optics and digital camera equipment that enhance the surgeon’s vision. In addition the evolution of instruments specifically for laparoscopic surgery has meant that procedures have become easier to perform and operating times have dramatically reduced, often equivalent to the open technique. This has considerable benefits for patients who significantly gain by avoiding an open procedure (Box 23.1), in particular the elderly and the obese, where increased postoperative mobility reduces the risk of immediate postoperative complications.

Technique

Patient position

The patient is placed flat in a modified lithotomy position with the hips flexed at 45° rather than the near 90° used for many other gynaecological procedures (Figs 23.3 and 23.4). The use of moveable stirrups allows the position of the legs to be altered intraoperatively. The flat position prevents bowel being displaced toward the umbilicus. The bladder should be emptied to reduce risk of injury and if required, a Spackman cannula can be introduced carefully to allow mobilization of the uterus.

Pneumoperitoneum

Prior to insertion of the operating ports, the peritoneum is commonly insufflated with carbon dioxide. Introduction of the gas can be either via a Veress needle or by insertion of the umbilical trocar using a ‘cut-down’ technique. The site of needle insertion is most commonly the umbilicus, but other sites that have been used, include suprapubically and the fundus of the uterus. In patients who have had previous abdominal surgery, Palmer’s point (defined as two finger-breadths below the left costal margin in the mid-clavicular line) may be used and an umbilical port inserted under direct vision at the umbilicus if bowel adhesions are absent. Once the pneumoperitoneum has been created, subsequent ports may be introduced, but always under direct vision. The inferior epigastric vessels can be identified to avoid injury prior to any lateral port insertion. Any instruments being inserted into or removed from the peritoneum must be visualized to avoid inadvertent injury. At the end of the procedure, any trocar site with a diameter > 10 mm should have the underlying sheath closed to avoid a Richter hernia. Gas should be expelled to reduce referred shoulder-tip pain and trocars removed under direct vision.

Postoperative management

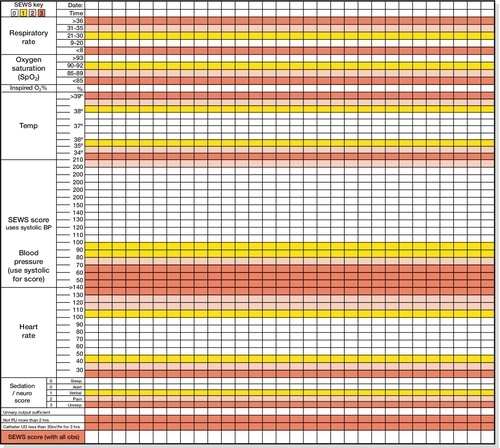

Immediate postoperative care is geared to identify potential complications arising from the surgery or new onset medical complications secondary to the physiological stresses of surgery and anaesthesia. Regular recording of temperature, pulse, blood pressure, respiratory rate and urine output help early recognition of an adverse event. These physiological parameters can be recorded as a combined score (e.g. Scottish Early Warning Scoring ‘SEWS’ system) that helps provide an early warning of a patient’s deteriorating condition and mandates early medical review (Fig. 23.5).

The use of anti-thromboembolic (TED) stockings and low molecular weight heparin help minimize venous thromboembolic problems (VTE). Early mobilization and maintenance of hydration also help to minimize the risk of DVT. Rather than traditional bed rest and fasting post-surgery, emphasis is now placed on ‘enhanced recovery’, where the patient is allowed oral fluids and diet early in the postoperative period, and the use of intra-abdominal drains, naso-gastric tubes and urinary catheters is kept to a minimum. Attention is also focused on good pain relief and prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting.

Postoperative complications

Postoperative complications can be classified with regard to their timing related to the surgery, i.e. intraoperative, immediate postoperative period and the delayed postoperative period. Complications arising from surgery may include bowel, bladder or ureter injury; the management of these are beyond the scope of this chapter but may require the assistance of a general surgeon or urologist. Intraoperative bleeding can be profuse and difficult to arrest if the vessels retract into the pelvic sidewall. Care must be taken to identify the bowel, bladder and ureter, as frantically placed sutures can lead to their injury and complicate surgery further. Clear communication with the anaesthetist is essential to enable circulatory support and issue of blood products.

Immediate postoperative complications can also include bleeding and this is often masked in the younger patient by their ability to compensate physiologically for blood loss. However, the combination of abdominal pain, developing tachycardia and oliguria should raise suspicions of bleeding. It may not be until the patient is in extremis before the blood pressure significantly drops. Postoperative pyrexia is common and has multiple causes. Basal atelectasis, bacteraemia and VTE should be considered and managed accordingly. Unrecognized bowel injury may reveal itself within the first 24 h but ureteric obstruction may not become symptomatic until day 4 postoperatively. Incidence of wound infections is reduced by a strict hand hygiene policy and intraoperative antibiotics. These may be continued further in those at high risk of wound infection, i.e. the obese, diabetics or those on steroid medication.

Voiding of urine can be affected by many gynaecological procedures – pain in itself can result in urinary retention, so close attention to fluid balance should be given in the immediate hours following surgery in those without a urinary catheter. Following removal of the catheter complete emptying of the bladder should be demonstrated as residual volumes of urine can predispose to ascending urinary tract infection.

Delayed complications may involve delayed wound healing, VTE, bladder dysfunction, chronic pain, lymphoedema or lymphocyst formation and genital tract fistulae.