11

Heavy menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhoea

Heavy menstrual bleeding

Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) is defined, for clinical purposes, as bleeding that has an adverse impact on the quality of life of a woman; it may occur alone or with other symptoms. Menstrual blood loss can be measured, but this is usually only performed for research purposes. HMB was often called ‘menorrhagia’ in the past, but this term is better avoided as it means different things to different people, e.g. in the USA the definition is different from that in the UK. HMB is the commonest cause of iron-deficiency anaemia in women in the affluent world.

Menstrual problems are becoming more prevalent, since women experience more periods in their lifetime than did their predecessors 100 years ago (approximately 400 periods vs 40). This is because women have fewer children and breastfeed less (lactational amenorrhoea). Only 50% of women who complain of excessive heavy bleeding, however, actually suffer from loss that falls outside the normal range for a population of women not complaining of any menstrual abnormality (> 80 mL/month).

The medical and surgical treatment of HMB is also an appreciable burden to health-service resources. HMB is a common indication for hysterectomy, although the numbers have fallen in the last 10 years with the introduction of alternative, effective treatments. Although a commonly performed operation, hysterectomy is a major surgical procedure and its use needs to be balanced against the potential associated mortality and morbidity. Satisfaction rates with hysterectomy are, however, very high.

Causes of HMB

The causes are summarized in Table 11.1.

Table 11.1

The main causes of HMB

| 1. Uterine pathology, e.g. fibroids | Common |

| 2. No apparent cause | Very common |

| 3. Medical disorders, including clotting defects |

Very rare |

Uterine pathology

HMB is associated with both benign pathology (e.g. uterine fibroids, endometrial polyps, adenomyosis, pelvic infection) and, extremely rarely, malignant pathology (e.g. endometrial cancer). Over half of those women with an excessively heavy loss of > 200 mL will have fibroids. With the advent of high quality ultrasound that is easily available in outpatient clinics, pathology is identified in a greater proportion of women.

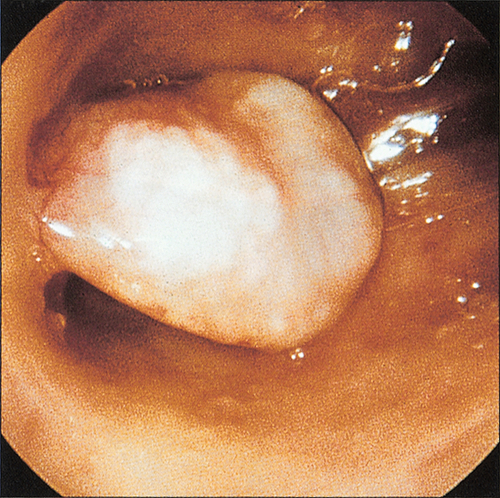

Endometrial polyps are common benign localized overgrowths of the endometrium. They consist of a fibrous tissue core covered by columnar epithelium, and it is believed that they arise as a result of disordered cycles of apoptosis and regrowth of endometrium. Although it is uncertain that they cause HMB, it is likely that intrauterine endometrial polyps do increase the likelihood of irregular bleeding (Fig. 11.1). It is unlikely, however, that small endocervical polyps detected at the time of a routine cervical smear cause the same effect. Malignant change of such a polyp is very rare.

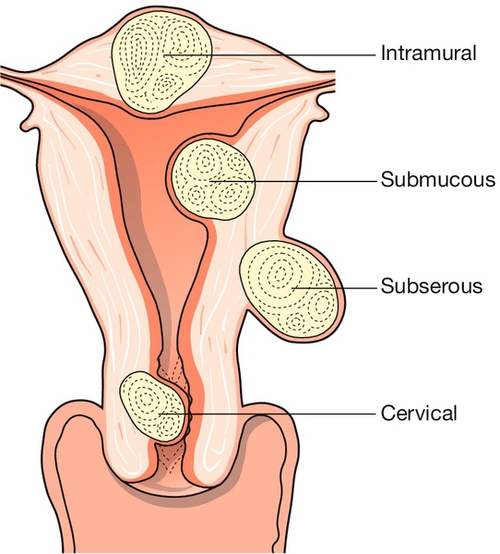

Uterine fibroids (leiomyomas) are benign tumours of the myometrium, which are present in approximately 20% of women of reproductive age. They are well-circumscribed whorls of smooth muscle cells with collagen and may be single or multiple (Fig. 11.2). Size varies from microscopic growths to tumours that weigh as much as 40 kg and they are more common in women of Afro-Caribbean origin. Sub-mucous fibroids project into the uterine cavity, intramural fibroids are contained within the wall of the uterus, and subserosal fibroids project from the surface of the uterus; cervical fibroids arise from the cervix.

Many are asymptomatic, but when symptoms do occur, they are often related to the site and/or size of the fibroid. Presenting symptoms include menstrual dysfunction, infertility, miscarriage, dyspareunia and pelvic discomfort. The mechanism by which fibroids adversely affect reproduction is unclear, but may be related in part to distortion of the uterine cavity affecting implantation. It is unlikely that fibroids not distorting the cavity have an adverse impact. Fibroids may also present because of pressure effects on surrounding organs, such as frequency of micturition as a result of pressure on the bladder, or even hydronephrosis due to ureteric compression. Growth of fibroids is mediated by sex steroids, particularly oestrogen and they therefore grow during pregnancy and shrink after the menopause. Occasionally during pregnancy, necrosis of the fibroid (‘red degeneration’) leads to acute abdominal pain. The incidence of malignant change (leiomyosarcoma) in fibroids is considered to be extremely low (0.1%).

HMB in the absence of pathology

This was known in the past as ‘dysfunctional uterine bleeding’, but again, this term should be avoided. HMB in the absence of recognizable pelvic pathology or systemic disease is a diagnosis of exclusion and is probably the commonest ‘diagnosis’ reached after investigating women with HMB. Some HMB with no pathology may be ‘anovulatory’ or ‘ovulatory’, although clinically, this is not an important distinction, as treatment is the same in both cases. The underlying cause is likely to reside at the level of the endometrium, although the precise nature of the vascular and endocrine abnormality remains elusive.

Medical disorders and clotting defects

Very rarely, HMB is associated with such medical problems as thyroid disease (both hypo- and hyperthyroidism), hepatic disease and renal disease (although the majority of those with end-stage renal failure are amenorrhoeic). Other symptoms of the disorder are likely to be present.

Certain coagulation abnormalities (e.g. von Willebrand disease) and platelet defects (e.g. thrombocytopenia) are associated with an increased incidence of HMB.

Assessment of HMB

History

The number of sanitary towels used, duration of bleeding or passage of clots, seems to have little correlation with the actual volume of blood lost. However, complaints of ‘flooding’ (leakage of heavy blood loss onto clothing) and having to use ‘double sanitary protection’ (pad and tampon) to prevent leakage of blood onto clothes are indicative of HMB and are likely to have a negative impact upon the woman’s quality of life. It is important, therefore, to ask about the degree of inconvenience experienced, such as time lost from work, or becoming housebound during menses, owing to fear of social embarrassment from an episode of flooding in public.

A history of irregular bleeding, dyspareunia, pelvic pain or intermenstrual or post-coital bleeding may raise the suspicion of underlying pathology and often require additional investigation. They can be termed ‘red light’ symptoms.

The woman should also be questioned about symptoms suggestive of anaemia, such as fatigue and light-headedness. A history suggestive of systemic disease such as a thyroid disorder or a clotting abnormality would signal that further investigation for such causes would be required. The woman should also be questioned about risk factors for endometrial cancer, such as use of unopposed oestrogen, tamoxifen use, polycystic ovary syndrome and family history of endometrial or colon cancer. It is also important to establish if she has a history of thromboembolism, as many medical treatments for HMB are hormonal and thus their use may be relatively or absolutely contraindicated.

Examination

The woman should be examined for signs of anaemia. An abdominal, bimanual and speculum examination should be considered. An enlarged, ‘bulky’ uterus suggests uterine fibroids, and tenderness suggests endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease or adenomyosis.

Investigations

Laboratory tests

A full blood count should be carried out in all women, to diagnose/exclude anaemia. Thyroid function tests and tests of coagulation should be performed only if there are features suggestive of this in the history. No other endocrine tests are routinely indicated.

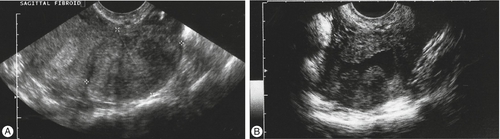

Ultrasound

A pelvic ultrasound scan should be performed if history or examination suggests structural uterine pathology, or if it is not possible to assess the uterus clinically because of obesity. The site and size of abnormalities such as fibroids can be determined, together with assessment of the ovaries (Fig. 11.3).

(A) A large intramural fibroid. (B) Two submucous fibroids projecting into the cavity of the uterus, which contains a small amount of fluid (saline infusion ultrasound scan).

Endometrial assessment

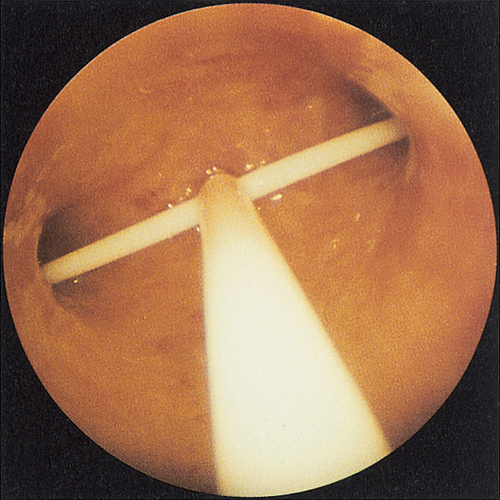

This should be performed in all women aged > 45 years, and in younger women with persistent HMB in spite of medical treatment, ‘red light’ symptoms such as irregular bleeding or for whom there are risk factors for endometrial cancer. This can take the form of an endometrial biopsy or a hysteroscopy, both of which can be carried out either as an outpatient or inpatient (Fig. 11.4) and p. 147.

Cervical cytology

This should be performed if it is due, or if the cervix looks suspicious.

Treatment of causes of HMB

Focal uterine pathology

Benign intrauterine polyps will usually be removed by polypectomy using hysteroscopic techniques. If malignant pathology is detected, then this should be treated as appropriate.

Fibroids may be treated medically or surgically.

Medical

Unfortunately, the symptoms caused by fibroids respond poorly to medical treatments such as those used where there is no pathology. Since growth of fibroids is hormone dependent, gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues (which result in hypo-oestrogenism) may be used to cause fibroid shrinkage. GnRH analogues are derivatives of natural GnRH, but peptide substitutions give the agonists greater potency and longer activity. Depot injection of the GnRH analogue, however, leads to pituitary downregulation with hypo-oestrogenism. Fibroids shrink by approximately 50% over 3 months of treatment, but regrowth occurs on cessation of treatment. During treatment, hypo-oestrogenism can result in symptoms such as hot flushes and also bone loss. In view of concern about osteoporosis, use of GnRH analogues is limited to short-term use (< 6 months). ‘Add-back’ hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is required to minimize the risk of osteoporosis and side-effects.

There is a new group of drugs known as ‘progesterone receptor modulators’ (such as ulipristal acetate) that are an exciting development in the treatment of fibroid-related HMB and possibly in the absence of pathology. They lead to rapid decrease in bleeding in 80% of women without leading to hypo-oestrogenism or inhibiting ovarian cyclicity. They are very well tolerated. Their use is currently restricted to 3 months, only because of unique changes in the endometrium, which are difficult to interpret. However, further clinical trials are ongoing.

Surgical

Hysteroscopic resection of small submucous fibroids is often possible, which can lead to improved fertility and relief of menstrual problems. Endometrial ablation in the presence of small fibroids is possible (see below).

If a woman wishes to conserve her fertility, myomectomy is an option. This involves incision of the pseudocapsule of the fibroid, enucleation of the bulk of the tumour and closure of the resulting defect. The operation is usually performed as an open abdominal procedure, although laparoscopic techniques are sometimes employed. Myomectomy is associated with a similar degree of morbidity to that of hysterectomy. There is a risk of haemorrhage (due to the vascularity of fibroids) and the small possibility that an emergency hysterectomy may need to be performed during surgery, to arrest uncontrollable bleeding. Furthermore, there is a risk of adhesion formation, which could compromise fertility (as a result of tubal obstruction), and the possibility that residual seedling fibroids may grow and lead to recurrence of fibroids. GnRH analogues are often used preoperatively to shrink the fibroids, with associated decreased intraoperative blood loss. Pregnancies after myomectomy are frequently delivered by planned caesarean section because of concern regarding uterine rupture in labour.

Uterine artery embolization (UAE), performed by interventional radiologists, is an effective and safe technique. It involves interruption of the blood supply to the fibroid by blocking the uterine arteries with coils or foam, delivered through a catheter placed in the femoral artery. The healthy myometrium revascularizes immediately, owing to the development of collateral circulations from vaginal and ovarian vessels. Fibroids, however, do not appear to revascularize, and shrink by about 50%, a reduction which appears to be sustained. Pain following occlusion of the vessels is often severe and usually requires opiate analgesia. Potential complications include infection, fibroid expulsion and the effects of exposure of the ovaries to ionizing radiation. The incidence of these is low and immediate morbidity is less than following hysterectomy, although pain and fever from post-embolization syndrome is not uncommon and deaths, though rare, have occurred. There are now several reported series of pregnancies following UAE; this treatment is therefore an option, after careful counselling, for women wishing to maintain their fertility.

If childbearing is complete and the woman is experiencing severe symptoms as a result of her fibroids, then hysterectomy may be considered (see below).

HMB with no pathology

In the majority of cases of HMB, no specific cause is found. Sometimes a woman is seeking reassurance that there is no pathology and does not necessarily wish treatment. For most women, however, treatment is requested. The following treatments may be considered.

Medical treatment

Intrauterine progestogens

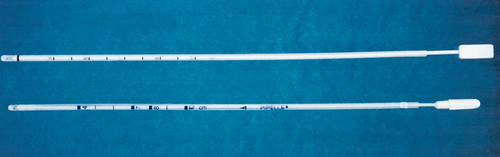

The levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) delivers progestogen directly to the uterus (Fig. 11.5) and is a first-line treatment for HMB, being particularly suitable for women requiring contraception: it is a highly effective reversible method of contraception and can stay in place for up to 5 years. After 12 months, menstrual blood loss is reduced by around 95% and many women are amenorrhoeic. The main problems with the LNG-IUS are the high incidence of irregular bleeding, particularly within the first 3–6 months after insertion, and an expulsion rate of 5%.

Prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) taken during menstruation reduce menstrual blood loss by around 25%, by reducing endometrial prostaglandin concentrations. The NSAID most commonly used for treatment of HMB is mefenamic acid, although other NSAIDs have not dissimilar efficacies. Side-effects include gastrointestinal complaints, dizziness and headache. These drugs are also of benefit for treating dysmenorrhoea.

Antifibrinolytics

Antifibrinolytics, such as tranexamic acid, work by inhibiting plasminogen activator, thereby reducing the fibrinolytic activity in the endometrium. This increases clot formation in the spiral arterioles and reduces menstrual loss. Tranexamic acid taken during menstruation reduces blood loss by around 50%. Gastrointestinal side-effects, nausea and tinnitus can occur. The drug should not be taken by women who are predisposed to thromboembolism.

The NSAIDs and antifibrinolytics are the best options for women wishing to conceive, since they are only taken during menstruation and do not suppress ovulation.

Combined oral contraceptive pill

This reduces blood loss by approximately 50%. Its mechanism for doing so is thought to be due to suppressive effects on the endometrium. There is no age restriction on use of the combined oral contraceptive in women at low risk (see p. 210).

Systemic progestogens

Oral progestogens are widely prescribed for HMB but overviews of well-designed trials of this therapy do not demonstrate a meaningful reduction in menstrual loss. Taken in a cyclical fashion, however, oral progestogens are often useful in regulating otherwise irregular cycles. If the depot injectable progestogen (medroxyprogesterone acetate) is administered for long enough, amenorrhoea frequently results. During initial months of use, however, bleeding can be unpredictable and heavy. Side-effects of progestogens include nausea, bloating, headache, breast tenderness, weight gain and acne.

GnRH analogues

Amenorrhoea occurs as a result of pituitary downregulation and thus inhibition of ovarian activity. Women may experience problems, however, associated with the resultant hypo-oestrogenism – particularly, hot flushes and vaginal dryness. GnRH analogues are usually reserved for short-term use only (up to 6 months) and add-back HRT is usually prescribed to relieve symptoms of hypo-oestrogenism.

Danazol

This is a synthetic androgen with anti-oestrogenic and anti-progestogenic activity, which reduces menstrual blood loss but is no longer recommended because of its poor side-effect profile, which includes irreversible virilization.

Surgical treatment

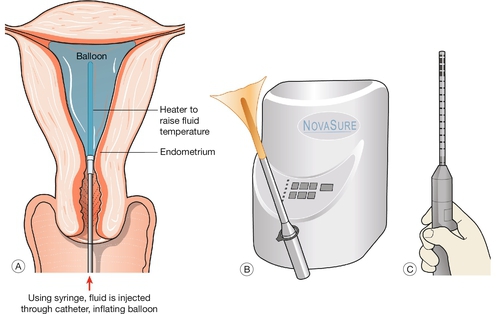

Endometrial ablation

Using a number of different techniques, it is possible to destroy most or all of the endometrium, thereby lessening or stopping menstrual loss altogether. Since endometrium regenerates from the basal layer, it is essential to ablate to the endomyometrial border. Endometrial ablation offers a safer method of symptom control, much shorter hospital stay and shorter recovery period than hysterectomy. Early techniques involved a hysteroscopic procedure under general anaesthesia during which the endometrium was treated, under direct visualization, with either laser or diathermy or by resection. Newer, non-hysteroscopic procedures include ablation with a heated balloon (e.g. Thermachoice, Cavaterm), bipolar radiofrequency impedance-controlled endometrial ablation (e.g. NovaSure), and other means are being developed all the time (Fig. 11.6). These newer procedures carry fewer risks than the hysteroscopic resections and some can be performed under local anaesthesia.

Fig. 11.6Conservative surgical treatments for menorrhagia.

(A) A thermal balloon; (B) impedance-controlled ablation; (C) microwave endometrial ablation.

The success rates of the different ablative techniques are broadly similar. All are associated with a 70–80% overall satisfaction rate, and an amenorrhoea rate of 20% for balloon treatment and around 50% for impedance-controlled ablation. Complications are rare but include uterine perforation, hyponatraemia and infection. Pregnancy is contraindicated after an ablation procedure and women are urged to use a reliable, if not permanent, form of contraception.

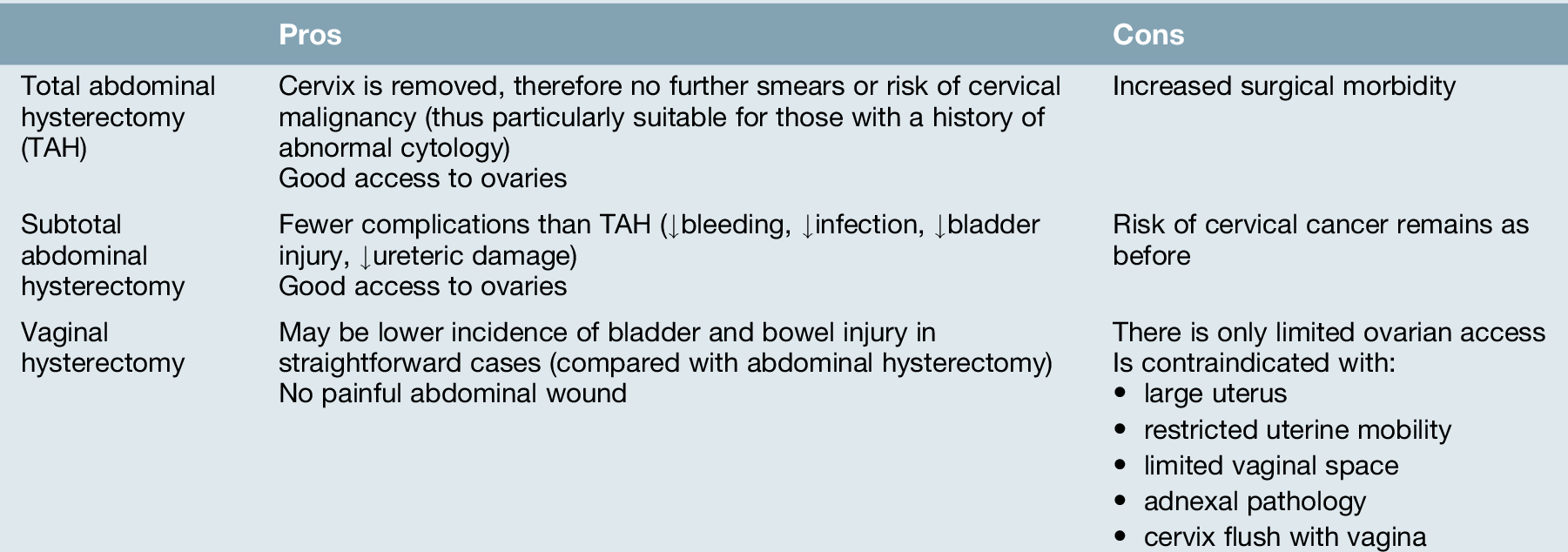

Hysterectomy

This is the only treatment that guarantees amenorrhoea and as a consequence, it is associated with a high level of satisfaction. Hysterectomy is performed by the abdominal or vaginal route, the latter with or without laparoscopic assistance (laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy or LAVH). Abdominal hysterectomy involves a laparotomy incision, which is usually transverse; a vaginal hysterectomy involves an incision through the vaginal wall. The choice between the two procedures depends on the size of the uterus, the degree of uterine descent, the wish to remove the ovaries (difficult by the vaginal route) and the skills and preferences of the surgeon (Table 11.2). Complications of hysterectomy include haemorrhage, bowel trauma, damage to the urinary tract, infection, postoperative thromboembolism and risk of vaginal prolapse in later yearsComplications are significantly greater in those with uterine fibroidsWomen undergoing a vaginal procedure recover more quickly from the operation than do those undergoing an abdominal hysterectomy, but the incidence of major complications, although low, is slightly higher with the vaginal route.

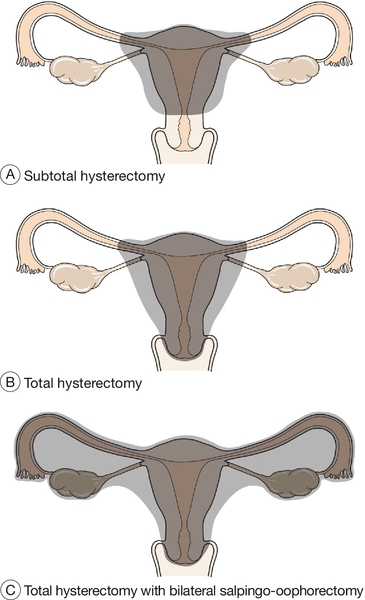

For women with no pathology who are undergoing an abdominal hysterectomy and who have a history of normal cervical cytology, there is the choice of having a ‘subtotal’ hysterectomy. This involves removing the body of the uterus but leaving the cervix behind. The advantages of a subtotal compared with a ‘total’ hysterectomy are that the operation is quicker, with less risk of damage to structures surrounding the cervix (bowel and urinary tract) (Fig. 11.7). There are also reported, but unproven, advantages of less disruption to the bowel, bladder and sexual functioning postoperatively. If the cervix is left, the surgeon must be careful to remove any residual endometrium in the cervical canal at the time of surgery. This is to minimize the small risk that menses would continue from the endometrium in the cervical canal. The disadvantages of a subtotal hysterectomy are that the woman must continue in the cervical cytology screening programme. The risk of cervical cancer arising in the stump of the cervix is extremely small (< 0.1%) provided that cervical cytology was normal prior to the operation.

Fig. 11.7Types of abdominal hysterectomy.

(A) Subtotal abdominal hysterectomy; (B) total abdominal hysterectomy; (C) total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

Whether to remove the ovaries at the time of abdominal hysterectomy depends on several factors, including the woman’s preferences, her age, her family history of breast or ovarian carcinoma and her attitude towards HRT. In someone who is 50 years old, it is unlikely that there will be much further ovarian function (average age of menopause 51), and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy will significantly reduce the incidence of later ovarian carcinoma and surgery for benign ovarian tumours. Residual ovaries (ovaries not removed at time of hysterectomy) may also occasionally cause chronic pain or dyspareunia if adherent to the vagina or side wall of the pelvis. In a woman who is 40, however, a further 10 years of ovarian oestrogen secretion may be expected and many women will not wish to take HRT for such a duration. It may therefore be appropriate to discuss ‘routine’ oophorectomy in women over 45 and ovarian conservation in women under 45. The decision must remain, however, a very individualized consideration.

Medical disorders and clotting defects

Referral should be made to the appropriate physician/haematologist to institute further investigation and treatment of the underlying condition.

Dysmenorrhoea

Excessive menstrual pain (dysmenorrhoea) is a significant clinical problem. It is characteristically a cramping lower abdominal pain, which may radiate to the lower back and legs and may be associated with gastrointestinal symptoms or malaise. It has been estimated that dysmenorrhoea affects 30–50% of menstruating women. It is also one of the most frequent causes of absenteeism from school and of days off work. As with heavy menstrual bleeding, dysmenorrhoea may be idiopathic (primary dysmenorrhoea) or due to pelvic pathology (secondary dysmenorrhoea).

Primary dysmenorrhoea

This generally begins with the onset of ovulatory cycles, typically within the first 2 years of the menarche. Pain is usually most severe on the day of menstruation or the day preceding this. There is good evidence that prostaglandins are involved in the aetiology, with higher concentrations of PGE2 and PGF2α in the menstrual fluid of women who suffer from dysmenorrhoea. PGF2α increases the contractility of the myometrium and can lead to the dysmenorrhoea pain.

Management of primary dysmenorrhoea

Pelvic examination may not be helpful in primary dysmenorrhoea and not appropriate when dealing with an adolescent. A transabdominal ultrasound scan will reveal normal pelvic organs and provide considerable reassurance to a young woman and her family. Discussion and reassurance are an essential part of the management. If dysmenorrhoea is unresponsive to standard medical therapy (see below), then consideration should be given to the possibility of underlying pathology and appropriate investigation instituted.

Treatment of primary dysmenorrhoea

Prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors

NSAIDs reduce the uterine production of PGF2α and thus dysmenorrhoea. Most NSAIDs have been shown to be effective treatments, but mefenamic acid and ibuprofen are preferred in view of their favourable efficacy and safety profiles.

Combined oral contraceptive pill

Suppression of ovulation with the combined contraceptive pill is highly effective in reducing the severity of dysmenorrhoea.

Depot progestogens

The injectable progestogen-only contraceptive suppresses ovulation and thus may be a useful treatment in alleviating dysmenorrhoea.

Levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS)

In addition to reducing menstrual blood loss, the LNG-IUS is effective at reducing dysmenorrhoea. Insertion of the device may, however, be difficult in those who have not been pregnant.

Secondary dysmenorrhoea

This is, by definition, associated with pelvic pathology. It usually has its onset many years after the menarche. Common associated pathologies are endometriosis, adenomyosis, pelvic infection and fibroids. It may also be associated with the presence of an intrauterine contraceptive device. In contrast, however, the LNG-IUS is associated with reduced dysmenorrhoea.

Management of secondary dysmenorrhoea

Women who have no other complaints but dysmenorrhoea and who have no abnormalities on abdominal, pelvic or speculum examination, may be safely treated without further investigation. Swabs from the genital tract, however, are helpful to exclude active pelvic infection, particularly Chlamydia trachomatis.

If pelvic masses such as fibroids are suspected, a pelvic ultrasound may be helpful. A laparoscopy is indicated if endometriosis or pelvic inflammatory disease is suspected, or for those women in whom standard medical therapy has been ineffective.

Treatment of secondary dysmenorrhoea

Treatment is dependent on the underlying pathology (see Chapter 13 for the management of endometriosis).