Granulomatous Inflammation

Introduction

Chronic granulomatous inflammation is a proliferative inflammation characterized by a cellular infiltrate of epithelioid cells [and sometimes inflammatory giant cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells, polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs), and eosinophils; see Chapter 1].

Post-Traumatic

Sympathetic Uveitis [Sympathetic Ophthalmia (SO), Sympathetic Ophthalmitis]

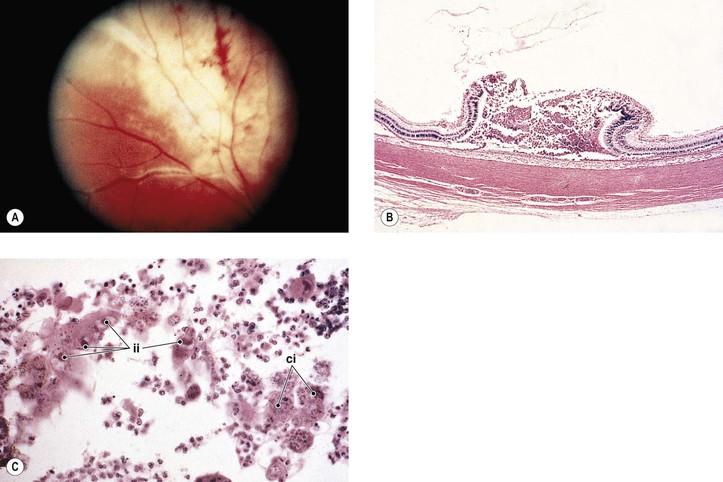

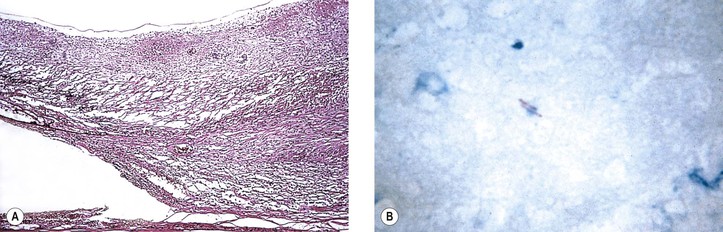

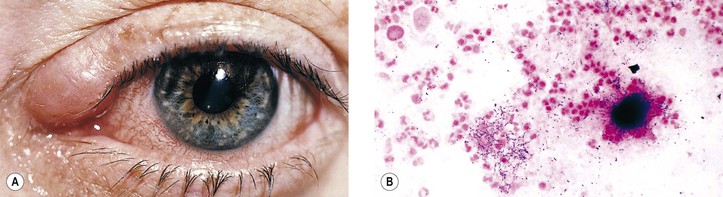

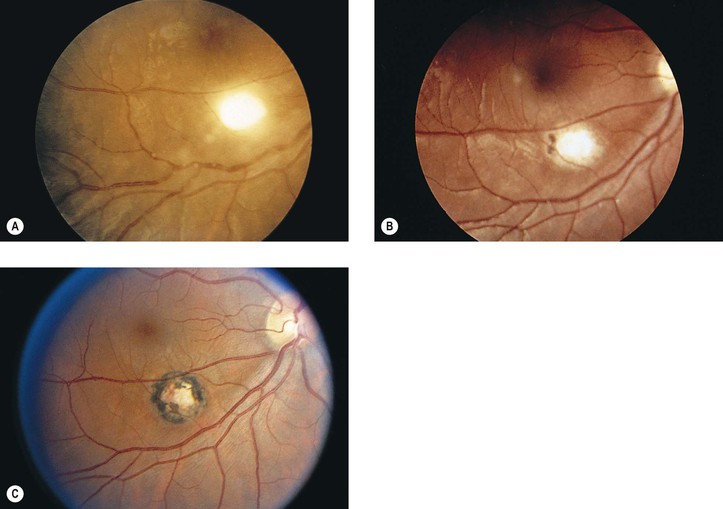

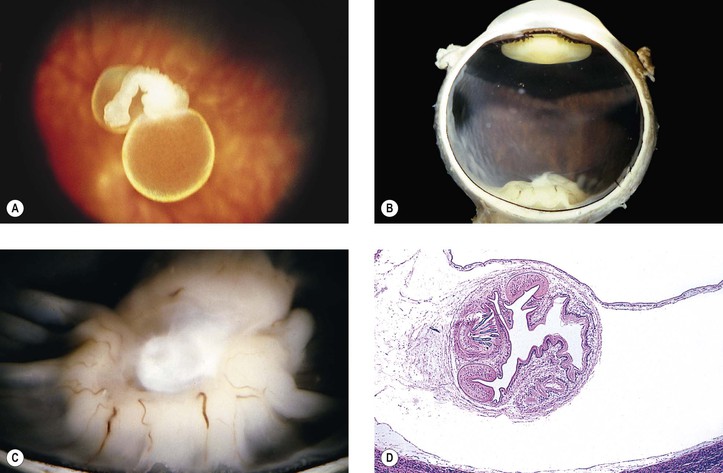

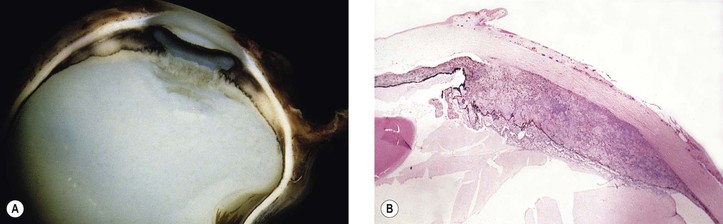

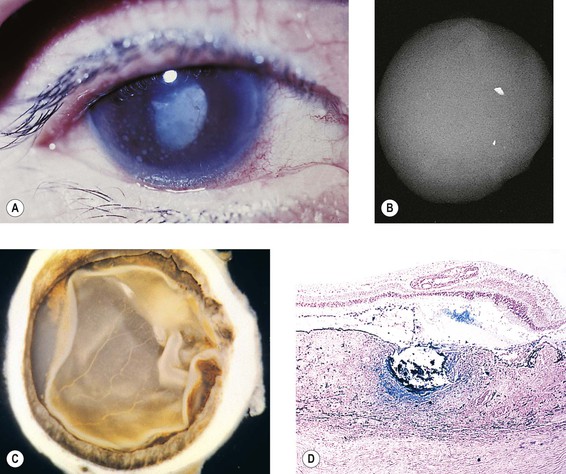

I. SO (Figs 4.1 and 4.2) is a bilateral, diffuse, granulomatous, T-cell-mediated uveitis that occurs from two weeks to many years after penetrating or perforating ocular injury and is associated with traumatic uveal incarceration or prolapse.

B. Removal of the injured eye before sympathetic uveitis occurs usually completely protects against inflammation developing in the noninjured eye.1 Once the inflammation starts, however, removal of the injured (“exciting”) eye probably has little effect on the course of the disease, especially after 3–6 months.

II. Blurred vision and photophobia in the noninjured (sympathizing) eye are usually the first symptoms. Vision and photophobia worsen concurrently in the injured (exciting) eye, and a granulomatous uveitis develops (see Fig. 4.1A).

III. The cause appears to be a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction of the uvea to antigens localized on the retinal pigment epithelium or on uveal melanocytes.

A. The lymphocytic infiltrate consists almost exclusively of T lymphocytes.

B. B cells found in some cases, usually of long duration, may represent the end stage of the disease.

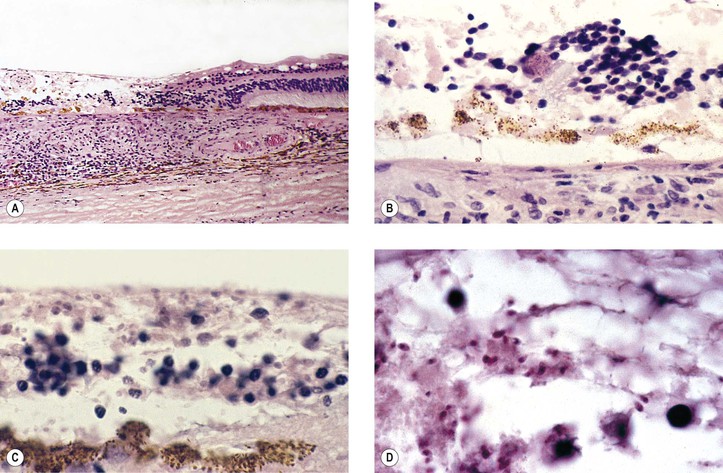

IV. Histologically, SO has certain characteristics that are suggestive of the disorder but not diagnostic.

A. Sympathetic uveitis is a clinicopathologic diagnosis, never a histologic diagnosis alone.

B. The following four histologic findings are characteristic of both sympathizing and exciting eyes:

2. Sparing of the choriocapillaris.

3. Epithelioid cells containing phagocytosed uveal pigment.

4. Dalen–Fuchs nodules (i.e., collections of epithelioid cells lying between Bruch’s membrane and the retinal pigment epithelium with no involvement of the overlying neural retina and sparing of the underlying choriocapillaris).2

1. Tissue damage caused by the trauma

2. Extension of the granulomatous inflammation into the scleral canals and optic disc

Phacoanaphylactic (Phacoimmune, Phacoantigenic, or Phacogenic) Endophthalmitis

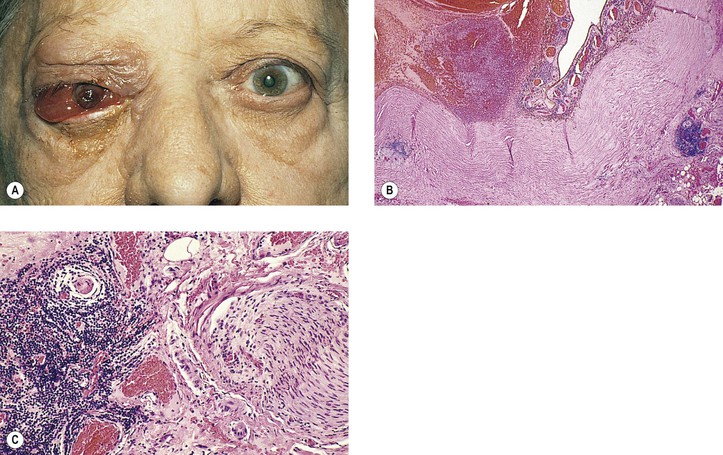

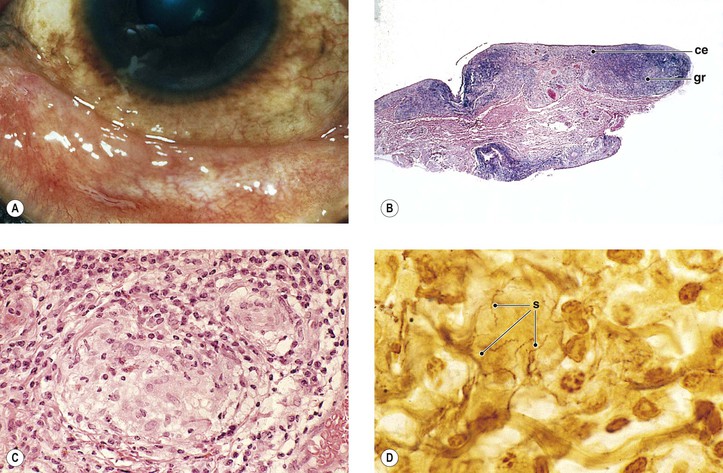

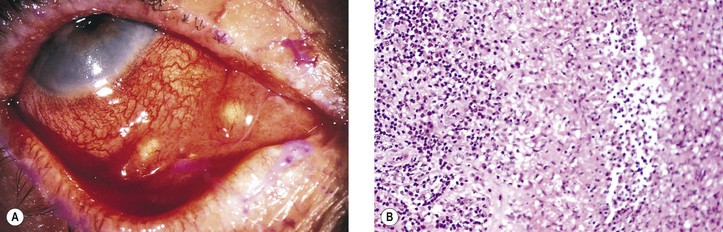

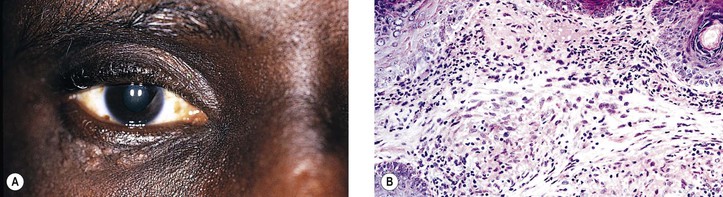

I. Phacoanaphylactic endophthalmitis (PE) (Fig. 4.3) is a rare, autoimmune, unilateral (sometimes bilateral if the lens capsule is ruptured in each eye), zonal, granulomatous inflammation centered around lens material. It depends on a ruptured lens capsule for its development.

II. The disease occurs under special conditions that involve an abrogation of tolerance to lens protein.

III. Histologically, in addition to the findings at the site of injury, a zonal granulomatous inflammation is found.

D. Usually the iris is encased in, and inseparable from, the inflammatory reaction.

Foreign-Body Granulomas

Nontraumatic Infections

Viral

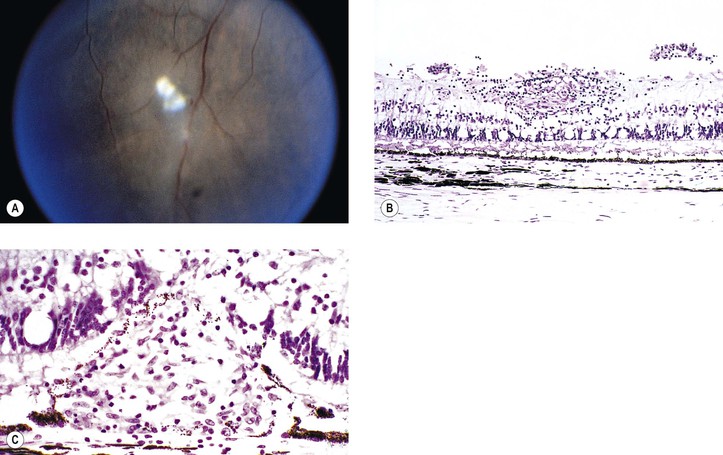

I. Cytomegalic inclusion disease (salivary gland disease; Fig. 4.4)

B. Clinically, a central retinochoroiditis, as seen in the congenital form, is similar to that seen in toxoplasmosis.

2. Neural retinal detachments may develop in 15% of affected eyes.

3. Other ocular findings include iridocyclitis, punctate keratitis, and optic neuritis.

C. Histologically, a primary coagulative necrotizing retinitis and a secondary diffuse granulomatous choroiditis are seen.

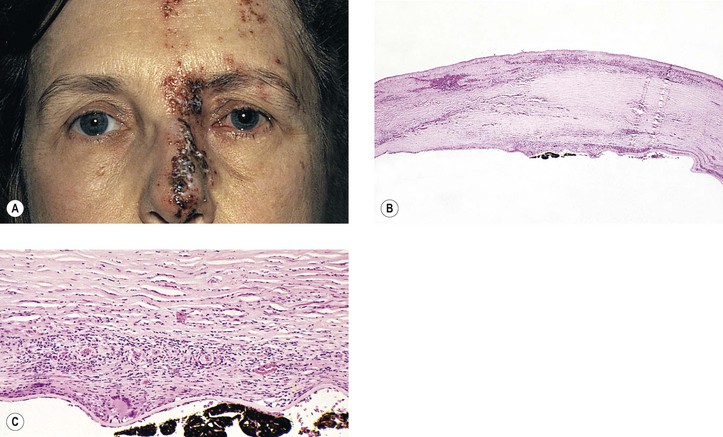

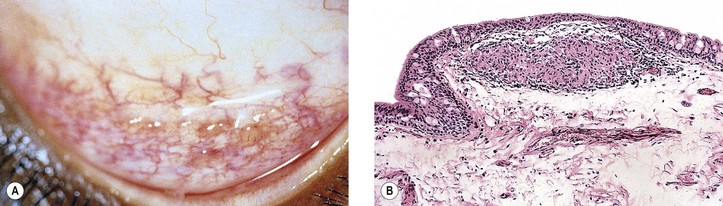

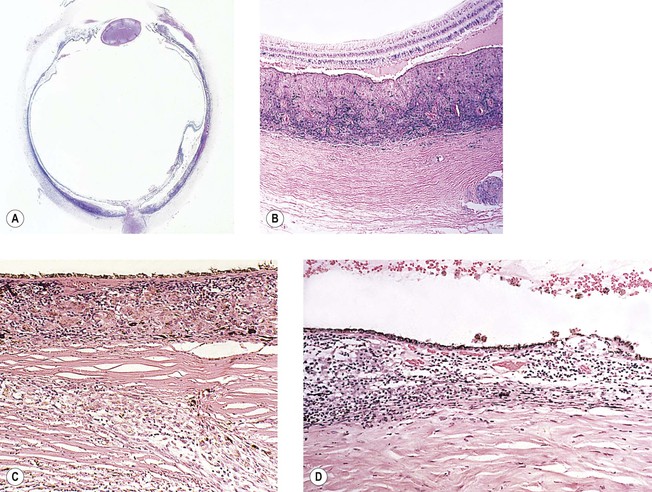

II. Varicella/herpes zoster virus (VZV; Figs 4.5 and 4.6)

A. VZV causes varicella (chickenpox) and herpes zoster (shingles).

2. Congenital infection is rare (differential diagnosis consists of the TORCH syndrome; see Chapter 3).

3. In immunocompetent individuals, VZV is a major cause of the acute retinal necrosis syndrome (see Chapter 11).

B. Ocular complications occur in approximately 50% of cases of herpes zoster ophthalmicus:

2. Anterior segment: iridocyclitis followed by peripheral anterior synechiae, exudate, and hyphema

Bacterial

I. Tuberculosis (Mycobacterium tuberculosis; Figs 4.7 and 4.8)

B. Tubercle bacilli reach the eye through the bloodstream, after lung infection.

D. Histologically, the classic pattern of caseation necrosis consists of a zonal type of granulomatous reaction around the area of coagulative necrosis.

II. Leprosy (Hansen’s disease; M. leprae; Fig. 4.9)

2. Histologically, a diffuse type of granulomatous inflammatory reaction, known as a leproma, is present.

b. The lepra cells and Virchow’s cells teem with beaded bacilli (no immunity).

B. In tuberculoid leprosy, the lepromin test is positive, suggesting immunity. The prognosis is good.

3. Histologically, a discrete (sarcoidal, tuberculoidal) type of granulomatous inflammatory reaction is seen, mainly centered around nerves.

III. Syphilis (Treponema pallidum; Fig. 4.10)

A. Both the congenital and acquired forms of syphilis may produce a nongranulomatous interstitial keratitis (see Chapter 8) or anterior or posterior uveitis. Syphilis may occur in immunologically deficient patients (e.g., those with AIDS).

B. Syphilis, a venereal disease, is divided into three chronologically overlapping stages.

The nonvenereal treponematoses caused by subspecies T. p. pertenue (yaws) and T. p. endemicum (bejel) are morphologically indistinguishable from T. pallidum and display only subtle immunologic differences.

2. Secondary stage: The period when the systemic treponemal concentration is greatest, usually 2–12 weeks after contact.

a. This stage may be manifest by fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy, and mucocutaneous lesions.

b. The secondary stage subsides in weeks to months but may recur within 1–4 years.

C. The common form of posterior uveitis is a smoldering, indolent, chronic, nongranulomatous inflammation.

2. A more virulent type of uveitis may occur with a granulomatous inflammation.

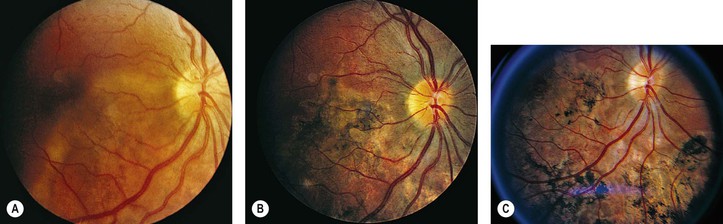

1. The chronic nongranulomatous disseminated form of posterior choroiditis:

2. The granulomatous form of posterior chorioretinitis:

b. Spirochetes can be demonstrated in the inflammatory tissue.

3. The preceding two types of reactions may also involve the anterior uvea.

IV. Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi; Fig. 4.11)

C. Like syphilis, Lyme disease is divided into three chronologically overlapping stages. Not all patients exhibit each stage, and the signs and symptoms are variable within each stage.

2. Stage 2 occurs within days, weeks, or even months and reflects systemic dissemination of the spirochete.

3. Stage 3 can follow a disease-free period and may last years.

a. “Lyme arthritis” is the hallmark of stage 3, appearing in more than 50% of untreated cases.

c. Ocular findings include stromal keratitis, episcleritis, orbital myositis, and cortical blindness.

V. Streptothrix (Actinomyces; Fig. 4.12)

A. The organism responsible for streptothrix infection of the lacrimal sac (see Chapter 6) and for a chronic form of conjunctivitis belongs to the class Schizomycetes, which contains the genera Actinomyces and Nocardia. The organism superficially resembles a fungus, but it is a bacterium, best classified as an anaerobic and facultative capnophilic bacterium of the genus Actinomyces.

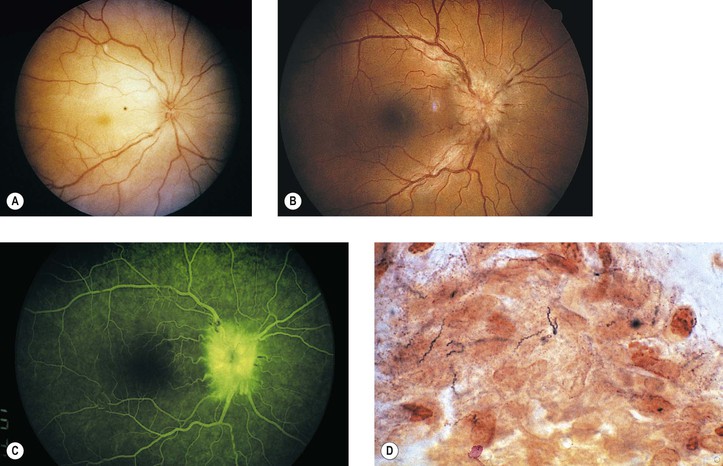

VI. Cat-scratch disease [CSD: Bartonella (previously called Rochalimaea) henselae, cat-scratch bacillus]

A. CSD is a subacute regional lymphadenitis following a scratch by a kitten or cat (or perhaps a bite from the cat flea, Ctenocephalides felis), caused by the cat-scratch bacillus, B. henselae, a slow-growing, fastidious, gram-negative, pleomorphic bacillus, which is a member of the α2 subgroup of the class Probacteria, order Rickettsiales, family Rickettsiaceae.

2. Ocular findings include Parinaud’s oculoglandular fever (see Chapter 7), neuroretinitis, branch retinal artery or vein occlusion, multifocal retinitis (retinal white-dot syndrome), focal choroiditis, intraretinal white spots, macular hole, optic disc edema associated with peripapillary serous retinal detachment, optic nerve head inflammation, and orbital infiltrates.

C. The domestic cat and its fleas are the major reservoir for B. henselae.

D. Histopathologically, the characteristics are discrete granulomas (which in time become suppurative) and follicular hyperplasia with general preservation of the lymph node architecture.

1. Warthin–Starry silver stain demonstrates the cat-scratch bacillus in tissue sections.

2. Electron microscopy shows extracellular rod-shaped bacteria.

VII. Tularemia (Francisella tularensis, also called Pasteurella tularensis; Fig. 4.13)

VIII. Other bacterial diseases

Fungal

I. Blastomycosis (Blastomyces dermatitidis, thermally dimorphic fungus)

A. North American blastomycosis may involve the eyes in the form of an endophthalmitis as part of a secondary generalized blastomycosis that follows primary pulmonary blastomycosis, or it may involve the skin about the eyes in the form of single or multiple elevated red ulcers.

1. Cutaneous blastomycosis does not usually become generalized.

II. Cryptococcosis (Cryptococcus neoformans, Torula histolytica)

III. Coccidioidomycosis (Coccidioides immitis)

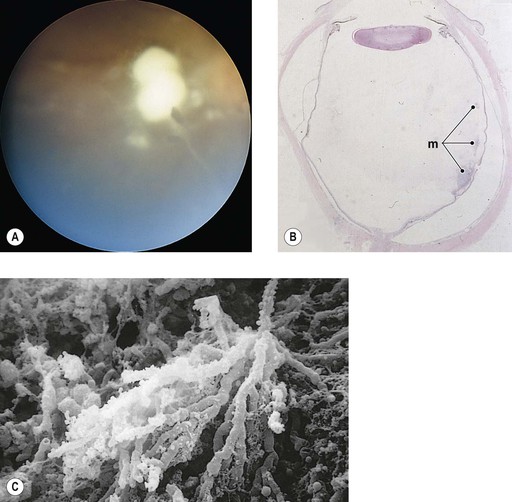

IV. Aspergillosis (Aspergillus fumigatus; Fig. 4.14B and C)

V. Rhinosporidiosis (Rhinosporidium seeberi)

A. Rhinosporidiosis is caused by a fungus of uncertain classification.

B. The main ocular manifestation of rhinosporidiosis is lid or conjunctival infection.

VI. Phycomycosis (mucormycosis, zygomycosis; see Fig. 14.7)

A. The family Mucoraceae of the order Mucorales, in the class of fungi Phycomycetes, contains the genera Mucor and Rhizopus, which can cause human infections called phycomycoses, usually in patients who have severe acidosis [e.g., diabetes, burns, diarrhea, and immunosuppression (see Chapter 14)] or iron overload (e.g., in primary hemochromatosis).

C. Histologically, the hyphae of Mucor and Rhizopus are nonseptate, very broad (3–12 µm in diameter), and branch freely.

2. Typically, the hyphae infiltrate and cause thrombosis of blood vessels, leading to infarction.

3. Inflammatory reactions vary from acute suppurative to chronic nongranulomatous to granulomatous.

VII. Candidiasis (Candida albicans; see Fig. 4.13A)

A. Candida albicans may cause a keratitis or an endophthalmitis.

VIII. Histoplasmosis (Histoplasma capsulatum)

Disseminated histoplasmosis with ocular involvement can be seen in immunologically deficient patients (e.g., in HIV-positive persons; see Chapter 11).

IX. Sporotrichosis (Sporotrichum schenkii)

A. Ocular involvement in sporotrichosis is usually the result of direct extension from primary cutaneous lesions of the lids and conjunctiva eroding into the eye and orbit.

1. Lesions in adjacent bony structures may encroach on ophthalmic tissues.

X. Pneumocystis carinii (PC; Fig. 4.15)

C. Clinically, choroidal lesions are yellow to pale yellow, usually seen in the posterior pole.

Parasitic

I. Protozoa

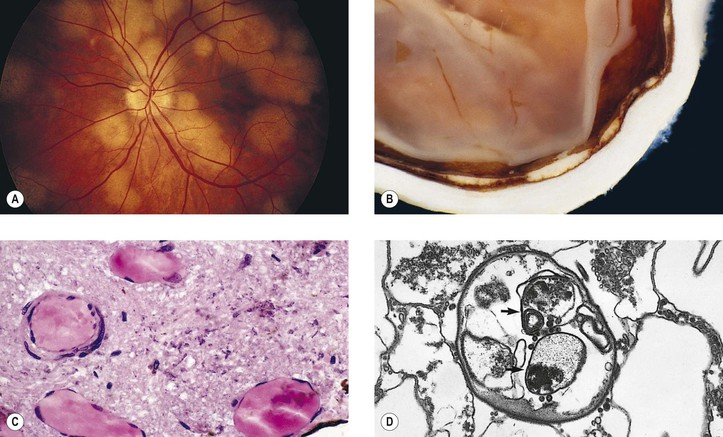

A. Toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma gondii; Figs 4.16 and 4.17)

2. The parasite primarily invades retinal cells directly.

5. Years later, reactivation can occur in the areas of the scars, or sometimes in new areas.

6. Both congenital and acquired forms are recognized.

b. The acquired form usually presents as a posterior uveitis and sometimes as an optic neuritis.

7. Histologically, the protozoa are found in three forms: free, in pseudocysts, or in true cysts.

a. Rarely, the protozoa may be found in a free form in the neural retina.

c. If the environment becomes inhospitable, an intracellular protozoan (trophozoite) may transform itself into a bradyzoite, surround itself with a self-made membrane, multiply, and then form a true cyst that extrudes from the cell and lies free in the tissue.

1) It is found in the late stage of the disease, at the time of remission.

2) The true cyst is resistant to the host’s defenses and can remain in this latent form indefinitely.

C. Microsporidiosis (Encephalitozoon, Enterocytozoon, Nosema, and Pleistophora)

D. Acanthamoeba species (A. casttellani, A. polyphaga, A. culbertsoni; see Chapter 8)

II. Nematodes

A. Toxocariasis (Toxocara canis; see Fig. 18.20)

1. Ocular toxocariasis is a manifestation of visceral larva migrans (i.e., larvae of the nematode T. canis). Rarely, Toxocara cati may also cause toxocariasis.

a. One eye tends to be involved, usually in children 6–11 years of age.

b. Rarely, bilateral ocular toxocariasis can be demonstrated by aqueous humor ELISA.

c. Often, the child’s history shows that the family possesses a puppy rather than an adult dog.

2. The condition may take at least three ocular forms:

b. A discrete lesion, usually in the posterior pole and seen through clear media

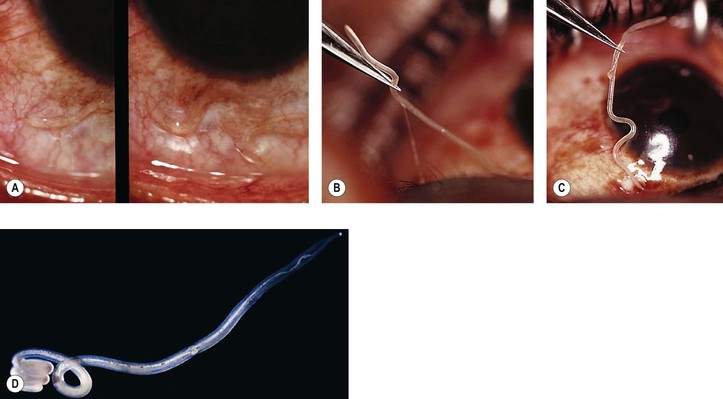

B. Diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis (DUSN; unilateral wipe-out syndrome)

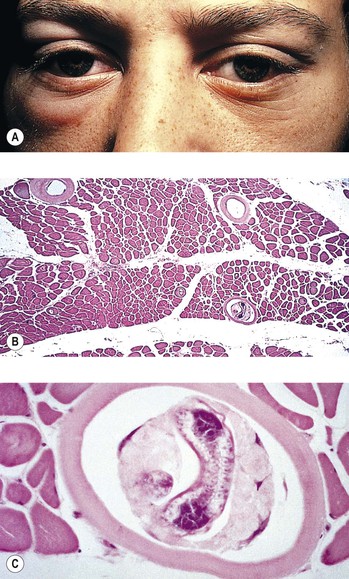

C. Trichinosis (Trichinella spiralis; Fig. 4.18)

2. Clinically, the lids and extraocular muscles may be involved as the larvae migrate systemically.

2. Histologically, little inflammatory reaction occurs while the worm is alive.

E. Dracunculiasis (Dracunculus medinensis; guinea worm; serpent worm)

2. Histologically, the worm, when dead, is surrounded by an abscess.

A. Cysticercosis (Cysticercus cellulosae; Fig. 4.20)

B. Hydatid cyst (Echinococcus granulosus)

2. In humans, the tapeworm has a predilection for the orbit.

C. Coenurus (Multiceps multiceps)

2. The bladderworm may involve the subconjunctival or orbital regions, or it may occur in the eye.

4. Histologically, multiple inverted scolices line up against an outer cuticular wall.

IV. Trematodes (flukes): Schistosomiasis (Schistosoma haematobium, S. mansoni, and S. japonicum)

V. Ophthalmomyiasis (fly larva)

VI. Retinal pigment epitheliopathy associated with the amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/parkinsonism–dementia complex of Guam—see Chapter 11.

Nontraumatic Noninfectious

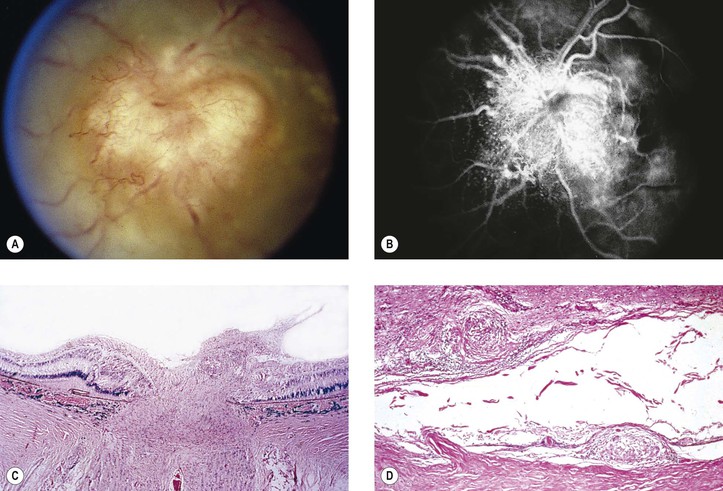

Sarcoidosis (Figs. 4.21–4.26)

III. The most common ocular manifestation is an anterior granulomatous uveitis that occurs in approximately one-fifth of people who have sarcoidosis.

IV. Histologically, a noncaseating, granulomatous, inflammation of the discrete (sarcoidal, tuberculoidal) type, frequently with inflammatory foreign-body giant cells, is found.

A. Most of the granulomatous nodules are approximately the same size.

B. Slight central necrosis may be seen, but caseation is rare.

D. Small granulomas may be present histologically in the submucosa of the conjunctiva even in the absence of visible clinical lesions.

1. The yield of positive lesions is higher, however, if a nodule is seen clinically.

Granulomatous Scleritis

I. Granulomatous scleritis, anterior or posterior (see Fig. 8.64), is associated with rheumatoid arthritis (or other collagen disease) in approximately 15% of patients (see section on Scleritis in Chapter 8), and approximately 45% have a known systemic condition.

II. Histologically, a zonal type of granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate surrounds a nidus of necrotic scleral collagen.

A. Typically, the inflammation is in the sclera between the limbus and the equator.

Chalazion

See Chapter 6.

Xanthogranulomas (Juvenile Xanthogranuloma and Langerhans’ Granulomatoses; Histiocytosis X)

See Chapter 9 and subsection on Reticuloendothelial System in Chapter 14.

Granulomatous Reaction to Descemet’s Membrane

I. In approximately 10% of eyes with corneal ulcer or keratitis that are examined histologically, a granulomatous reaction to Descemet’s membrane is found (see Fig. 4.5B and C). Most frequently, the corneas have a disciform keratitis with or without a history of herpes simplex or zoster keratitis.

Chédiak–Higashi Syndrome

See Chapter 11.

Allergic Granulomatosis and Midline Lethal Granuloma Syndrome

See section on Collagen Diseases in Chapter 6.

Weber–Christian Disease (Relapsing Febrile Nodular Nonsuppurative Panniculitis)

See Chapter 6.

Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada Syndrome (Uveomeningoencephalitic Syndrome)

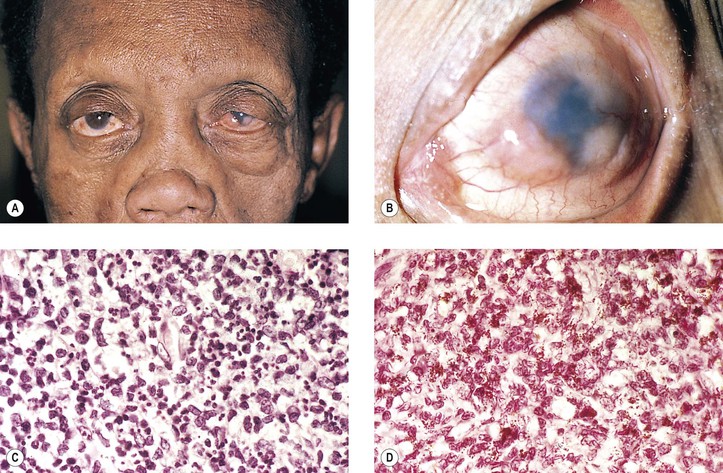

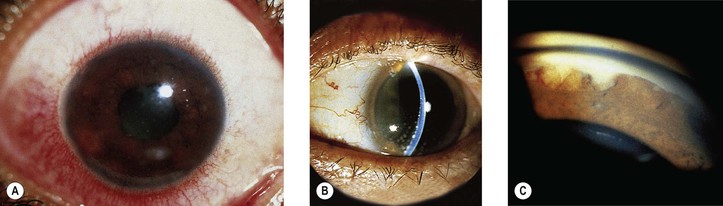

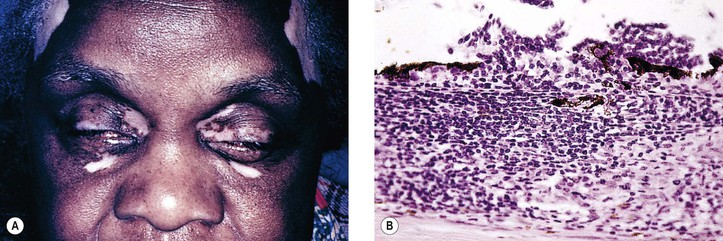

I. VKH syndrome (Fig. 4.27) is a multisystem disorder that reflects the integration of Vogt–Koyanagi syndrome with Harada’s disease.

B. VKH syndrome consists of a severe, acute, often bilateral, anterior uveitis associated with vitiligo (leukodermia), poliosis (whitened hair or canities), alopecia, and dysacusia. Perilimbal vitiligo in VKH syndrome is called Sugiura sign.

C. The cerebrospinal fluid shows increased protein levels and pleocytosis.

II. Autoaggressive cell-bound responses to uveal pigment may play a role in the histogenesis of VKH syndrome.

C. Also, T lymphocytes are decreased in the peripheral blood.

III. Histologically, a chronic, diffuse, granulomatous uveitis, closely resembling sympathetic uveitis, is seen.

Familial Chronic Granulomatous Disease of Childhood

II. FCGD is a heterogeneous group of disorders of phagocytic, oxidative metabolism.

B. The patients have a common phenotype of recurrent bacterial infections with catalase-positive microbes (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus and Serratia, Pseudomonas, Klebsiella, Chromobacterium, Escherichia, Nocardia, and Aspergillus species).

PMNs in patients with FCGD ingest bacteria but do not kill them because of a deficiency in leukocyte hydrogen peroxide metabolism. Furthermore, lysosomal hydrolytic enzymes (acid phosphatase and β-glucuronidase) are released in decreased amounts by PMNs during phagocytosis, resulting in abnormal (lessened) degranulation of the PMNs.

C. Humoral immunity, cell-mediated immunity, and inflammatory responses are normal.

III. Ocular findings include lid dermatitis, keratoconjunctivitis, and chorioretinitis.

IV. Histologically, suppurative and granulomatous inflammatory lesions characteristically coexist.

B. The choroid and sclera show multiple foci of granulomatous inflammation.

Access the complete reference list online at ![]()