Chapter 1 General Aspects of the Patient’s Neurologic History

The process of identifying a differential diagnosis should begin at the outset of questioning. In a broad sense, certain umbrella categories encompass virtually all etiologic mechanisms that underlie the differential diagnosis. Inevitably, there is some overlap (e.g., vascular occlusion in MELAS, a metabolic condition; mass effect of a brain abscess, an infectious condition). The fundamental pathologic processes, simplistically identified, are infectious, traumatic, metabolic, endocrinologic, toxic (exogenous and endogenous), congenital structural malformations, vascular, neoplastic, degenerative (usually of unknown or obscure cause), and idiopathic. Each of these categories has many subsets with which the clinician who evaluates neurologic problems in children must be familiar. The likelihood that one of the broad umbrella classifications applies to the problem of the pediatric patient must be judged while the history is obtained, during which time some categories will gain in probability and some will become increasingly remote. The information gathered during the history-taking session may be vital in the process of literature and database searches that may subsequently prove necessary. The precise role of genetic determination (i.e., gene product formation and use) in all familial pathologic processes is exceedingly important particularly now that the human genome has been mapped [Ali-Khan et al., 2009] and chromosomal microarray studies are available [Paciorkowsky and Fang, 2010]. Personalized genomic characterization will likely be utilized frequently in the immediate future [Guttmacher et al., 2010]. Results of newborn screening tests may be known by the caretakers and provide pertinent information [Duffner et al., 2009].

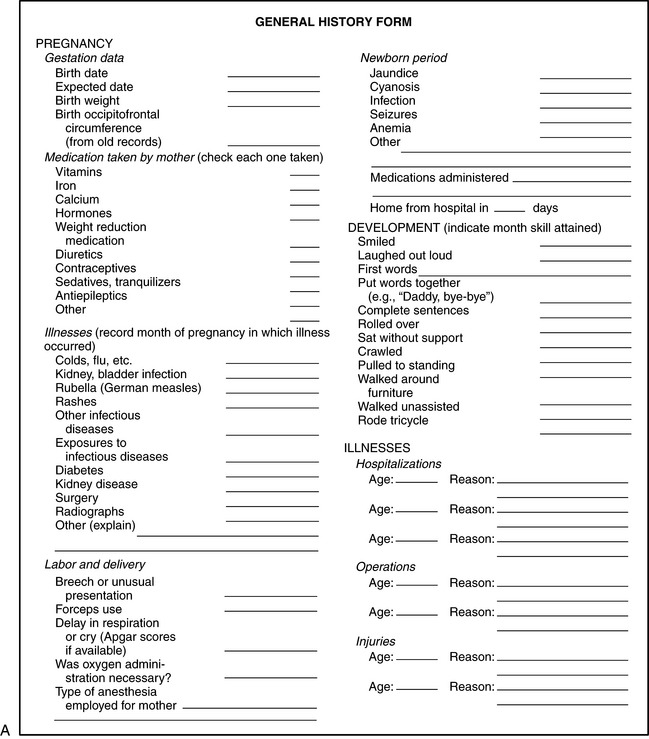

Review of past medical and developmental histories is an essential component of a good history-taking session. Information should be sought from records and from questioning the mother about health problems, including infertility, and diseases that occurred during pregnancy. With increasing data accumulating regarding adverse pediatric outcomes with assisted reproductive technologies [Jackson et al., 2004], it is important to ask whether conception was achieved naturally and, if not, what method of assisted reproductive technology was employed. Gestational information about infection, radiation, acute trauma, chronic illnesses such as diabetes mellitus, and toxins, including illicit drugs, tobacco, and alcohol, may prove invaluable. Further information about medications that the mother received, including over-the-counter preparations, should be probed.

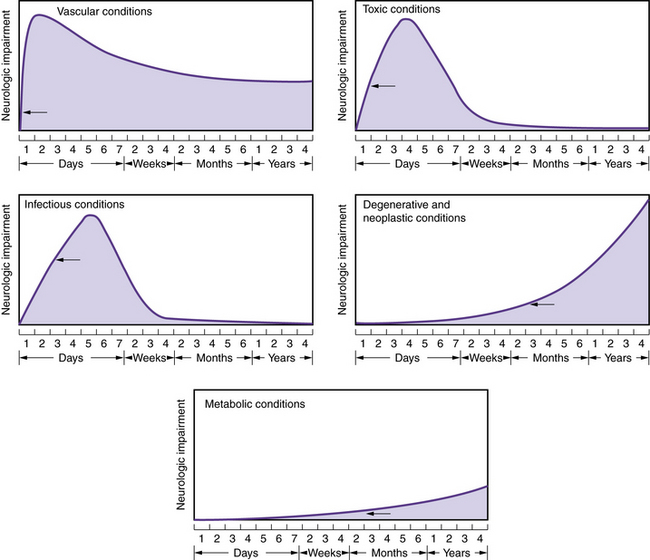

Sequelae of traumatic events develop over a period of minutes to a day (Figure 1-1). Although the clinical manifestations of cerebrovascular events normally develop over minutes to hours, the underlying process may be long-standing; therefore, acute onset of vascular symptoms may be the result of a subacute or chronic process. Infectious processes, electrolyte imbalances, and toxic processes (endogenous or exogenous) usually reach their zenith within a day to several days. Degenerative diseases, inborn metabolic disorders, and neoplastic conditions usually progress insidiously over weeks or months.

Fig. 1-1 Patterns of onset and courses of neurologic conditions.

The arrow in each graph signifies the point of clinical recognition.

(Adapted from Baker AB. Outline of Clinical Neurology. Dubuque, Iowa: William C Brown, 1958.)

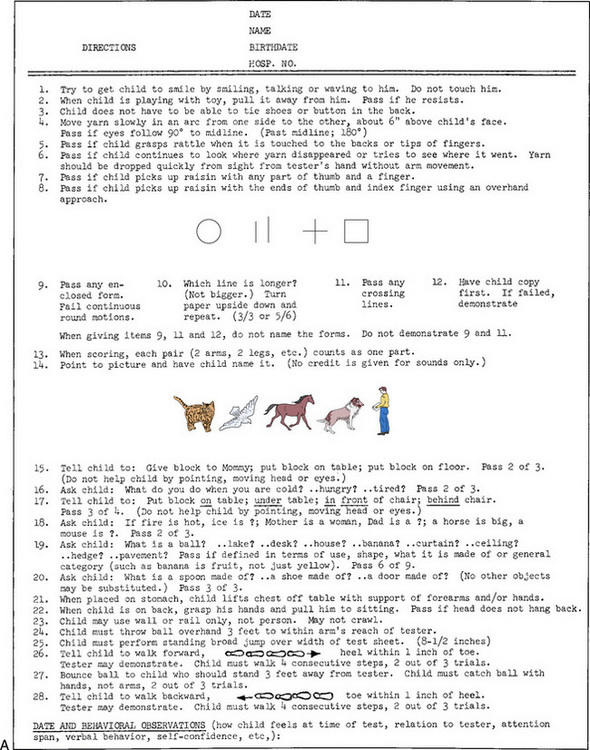

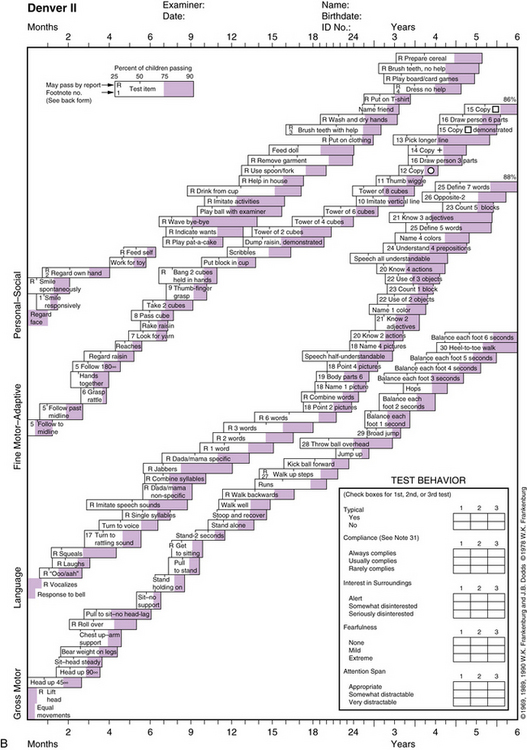

The Denver Developmental Screening Test (DDST) [Frankenburg and Dodds, 1967], the revised form [Frankenburg et al., 1981], the Denver II screening test (Figure 1-2) [Frankenburg et al., 1992], and other developmental surveys allow a more precise approach to the determination of whether gains or losses of skills have occurred and aid in the decision about whether a process is progressive or static.

Fig. 1-2 Denver Developmental Screening Test (Denver II) directions.

(From Frankenburg WK, Dodds JB, Archer P, et al. The Denver II: a major revision and restandardization of the Denver Developmental Screening Test. Pediatrics 1992;89:91.)

The Denver II differs from the DDST in the selected items, test form, and interpretation. The total number of items has been increased from 105 to 125, and items that were judged as difficult to administer or interpret have been modified or eliminated. Most of the new items are in the language section. The technical manual should be consulted if a delay is identified because it may be caused by sociocultural differences. The DDST II has been modified for use in different language and cultural norms [Lejarraga et al., 2002; Lim et al., 1994, 1996].

It is essential that examiners, caregivers, and educational personnel recognize that the Denver II provides an evaluation of the child’s current developmental level and is not a predictor of the future rate of development or eventual maximum attainment. The test may be used for early identification of neurologic deficits [Hallioglu et al., 2001]. Abnormalities in more complex and abstract functioning may not be recognizable until a later age and will require more sophisticated testing vehicles. Alteration in the child’s biologic or environmental status may affect developmental rate and achievement, and should be investigated and taken into account in the evaluation if appropriate.

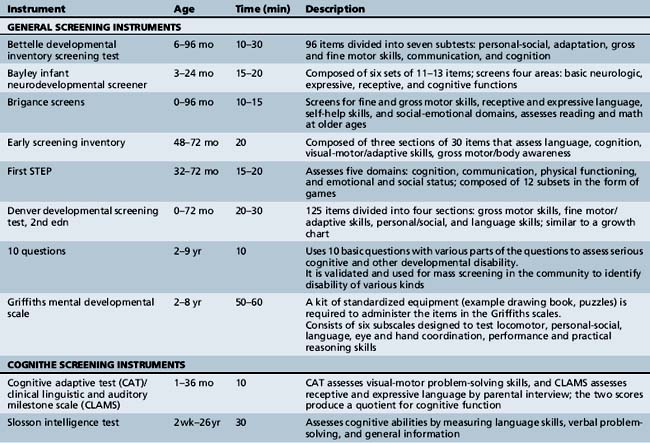

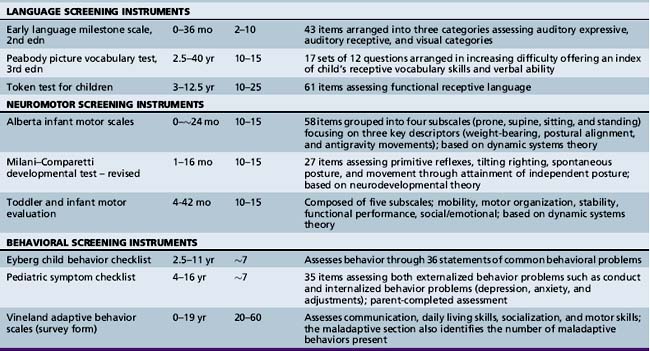

Various developmental screening instruments are available and their uses can be summarized briefly (Table 1-1) [Aly et al., 2010]. These instruments are useful when utilized in appropriate situations.

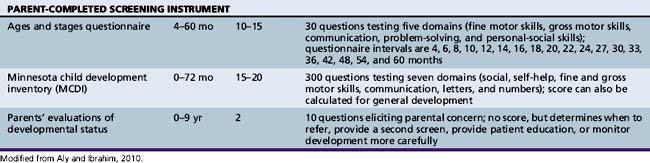

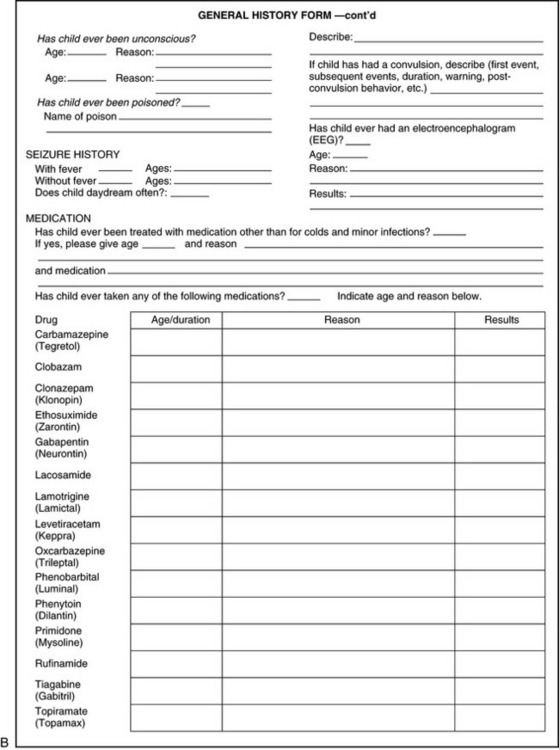

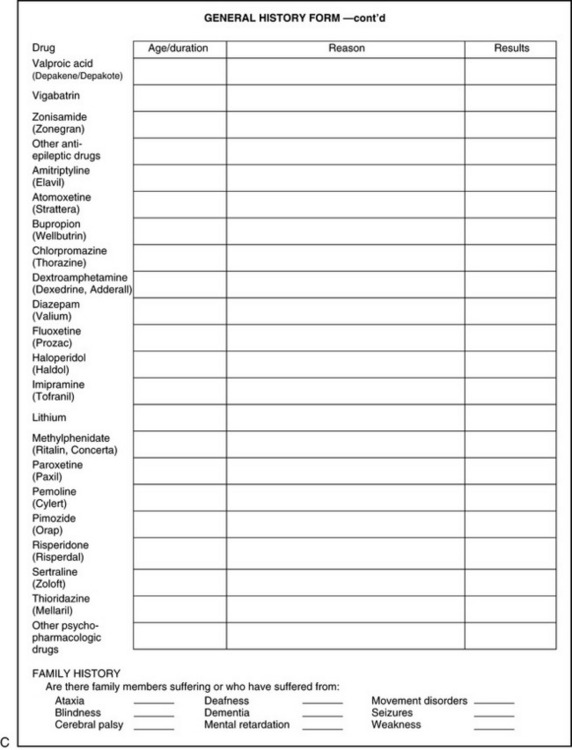

A specific form may be used by the examiner as a guideline to the history-taking procedure (Figure 1-3). There are many systems for recording history and the subsequent examination. The form printed in this chapter may be modified to the specific needs of the patient and the clinician.

Fig. 1-3 General history form.

(Courtesy of the Division of Pediatric Neurology, University of Minnesota Medical School.)

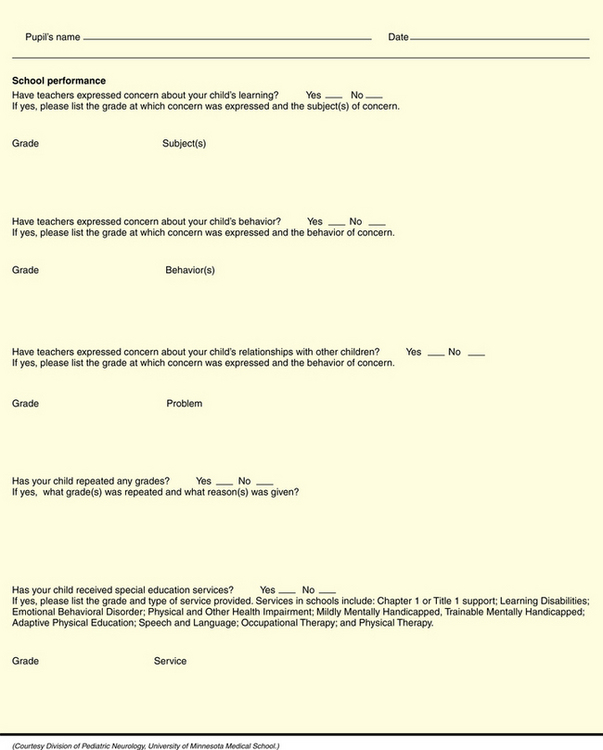

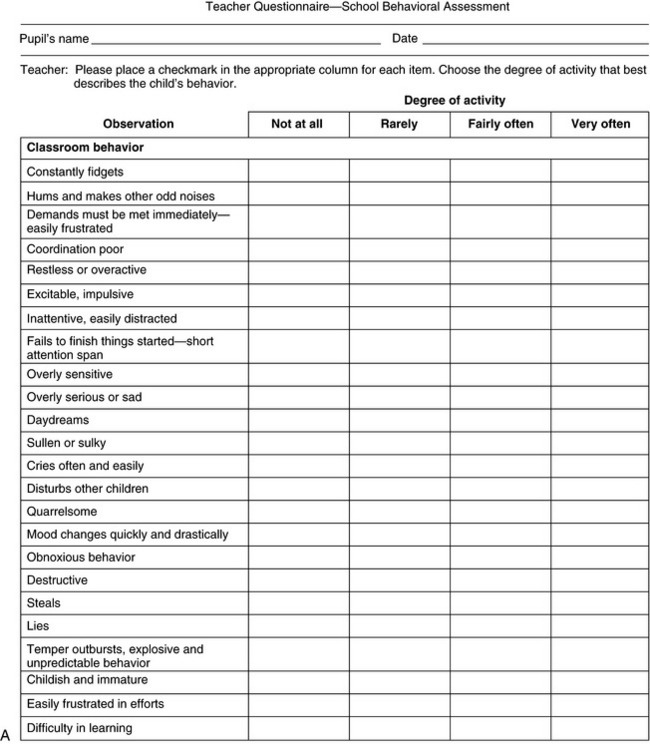

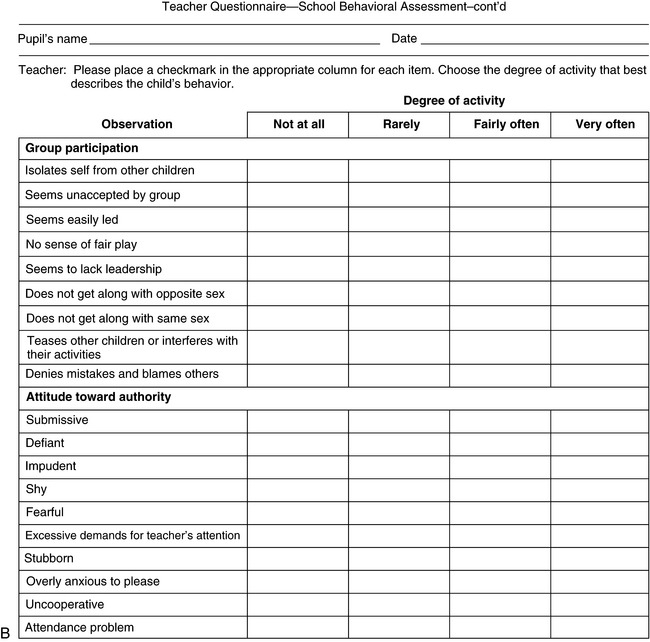

The question of hyperactivity is often at the core of the caregiver’s complaint. A rating scale may be completed by teachers to aid the clinician in diagnosis (Figure 1-4) [Connors, 1969]. The problem is discussed in more detail in Chapter 47. School behavior can also be assessed by caregivers, as shown in Box 1-1.

Fig. 1-4 Teacher questionnaire for behavioral assessment.

(Adapted from Conners CK. A teacher rating scale for use in drug studies with children. Am J Psychiatry 1967;126:884.)

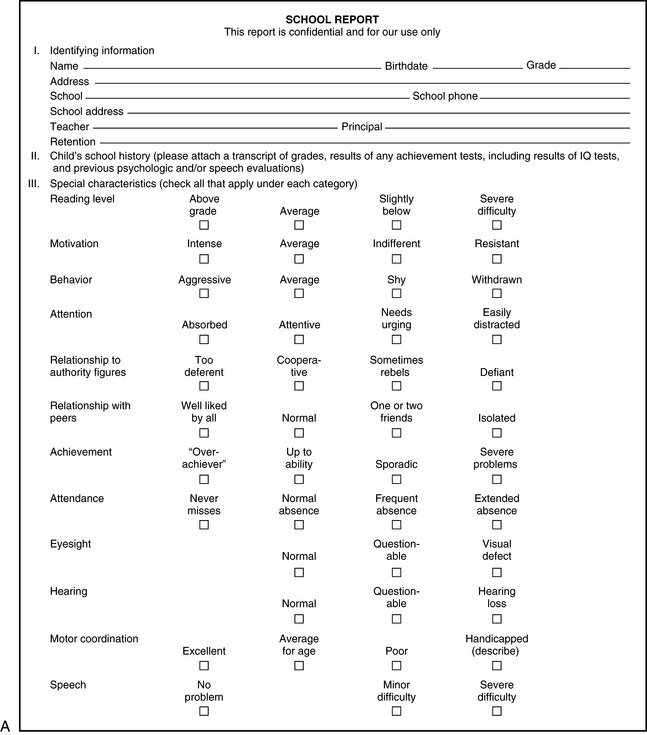

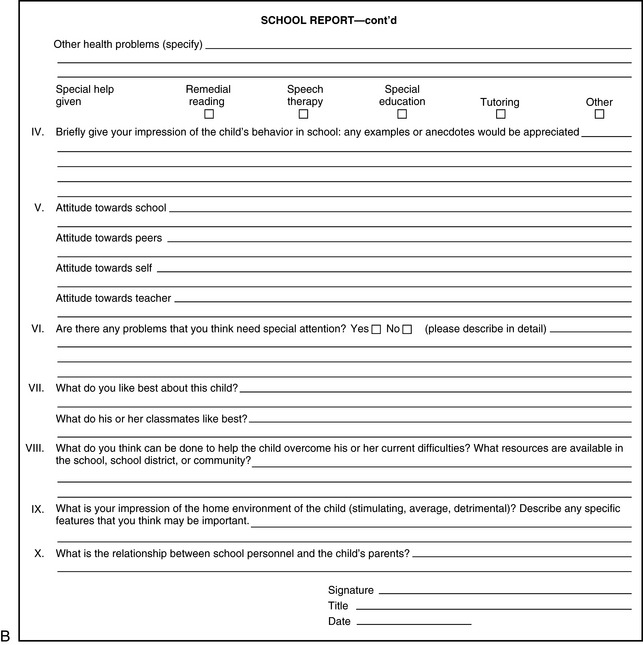

Many children are involved in some planned day activity, day care, or school program after the age of 2 or 3 years. A questionnaire, as in Figure 1-5, can be devised that will allow supervisory personnel to record intellectual, motor, and emotional characteristics.

Fig. 1-5 School information form.

(Courtesy of the Division of Pediatric Neurology, University of Minnesota Medical School.)

Autosomal-dominant traits may be present in successive generations, although the degree of expressivity may vary. Autosomal-recessive traits often do not manifest in successive generations but may be present in siblings. Consanguinity must be considered when autosomal-recessive disease is part of the differential diagnosis. X-linked recessive conditions are manifest in male siblings, male first cousins, and maternal uncles. Careful questioning of the mother, if possible, is highly desirable. Although mitochondrial diseases may be inherited through transmission of maternal DNA, paternal inheritance patterns are also possible [Schwartz and Vissing, 2003]. If a genetic condition is suspected, it is wise to examine siblings, parents, and other family members to augment the history.

References

![]() The complete list of references for this chapter is available online atwww.expertconsult.com.

The complete list of references for this chapter is available online atwww.expertconsult.com.

Ali-Khan S.E., Daar A.S., Shuman C., et al. Whole genome scanning: resolving clinical diagnosis management amidst complex data. Pediatr Res. 2009;66:357-363.

Aly Z., Taj F., Ibrahim S. Missed opportunities in surveillance and screening systems to detect developmental delay: A developing country perspective. Brain Dev. 2010;32:90.

Conners C.K. A teacher rating scale for use in drug studies with children. Am J Psychiatry. 1969;126:152.

Duffner P.K., Caggana M., Orsini J.J., et al. Newborn screening for Krabbe Disease: the New York State Model. Pediatr Neurol. 2009;40:245-252.

Frankenburg W.K., Dodds J.B. Denver developmental screening test. J Pediatr. 1967;71:181.

Frankenburg W.K., Fandal A.W., Sciarillo W., et al. The newly abbreviated and revised Denver Developmental Screening Test. J Pediatr. 1981;99:995.

Frankenburg W.K., Dodds J.B., Archer P., et al. The Denver II: A major revision and restandardization of the Denver Developmental screening test. Pediatrics. 1992;89:91.

Guttmacher A.E., McGuire A.L., Ponder B., et al. Personalized genomic information: preparing for the future of genetic medicine. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:161-165.

Hallioglu O., Topaloglu A.K., Zenciroglu A., et al. Denver developmental screening test II for early identification of the infants who will develop major neurological deficit as a sequelae of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatr Int. 2001;43:400.

Jackson R., Gibson K.A., Wu Y.W., et al. Perinatal outcomes in singletons following in vitro fertilization: A meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:551.

Lim H.C., Chan T., Yoong T. Standardisation and adaptation of the Denver Developmental Screening Test (DDST) and Denver II for use in Singapore children. Singapore Med J. 1994;35:156.

Lim H.C., Ho L.Y., Goh L.H., et al. The field testing of Denver Developmental Screening Test Singapore: A Singapore version of Denver II Developmental Screening Test. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1996;25:200.

Lejarraga H., Pascucci M.C., Krupitzky S., et al. Psychomotor development in Argentinean children aged 0–5 years. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2002;16:47.

Paciorkowsky A.R., Fang M. Chromosomal microarray interpretation: What is a child neurologist to do? Pediatr Neurol. 2009;41:391-398.

Schwartz M., Vissing J. New patterns of inheritance in mitochondrial disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;310:247.