Fungal infections

Fungi are responsible for an increasing proportion of CNS infections. Contributory factors include:

The widespread use of immunosuppressive drugs.

The widespread use of immunosuppressive drugs.

An increase in the relative number of elderly individuals in many Western populations, associated with an increase in the incidence of certain malignant diseases.

An increase in the relative number of elderly individuals in many Western populations, associated with an increase in the incidence of certain malignant diseases.

The commonest presentations are:

The manifestations of CNS infection partly reflect the form and size of the organism involved:

Yeasts are not large enough to occlude capillaries and tend to produce leptomeningitis.

Yeasts are not large enough to occlude capillaries and tend to produce leptomeningitis.

Hyphal forms obstruct large and medium-sized arteries and cause extensive infarcts, such as occur in aspergillosis and mucormycosis.

Hyphal forms obstruct large and medium-sized arteries and cause extensive infarcts, such as occur in aspergillosis and mucormycosis.

Pseudohyphae, such as those of Candida, occlude small parenchymal blood vessels (arterioles), producing immediately adjacent small infarcts that rapidly evolve into microabscesses.

Pseudohyphae, such as those of Candida, occlude small parenchymal blood vessels (arterioles), producing immediately adjacent small infarcts that rapidly evolve into microabscesses.

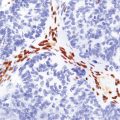

Staining techniques such as the periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) method and methenamine silver impregnation are valuable for identifying fungi in tissue sections. More recently, immunohistochemical reagents that facilitate accurate diagnosis of some fungal infections have become available (Table 17.1).

FILAMENTOUS FUNGI (MOLDS)

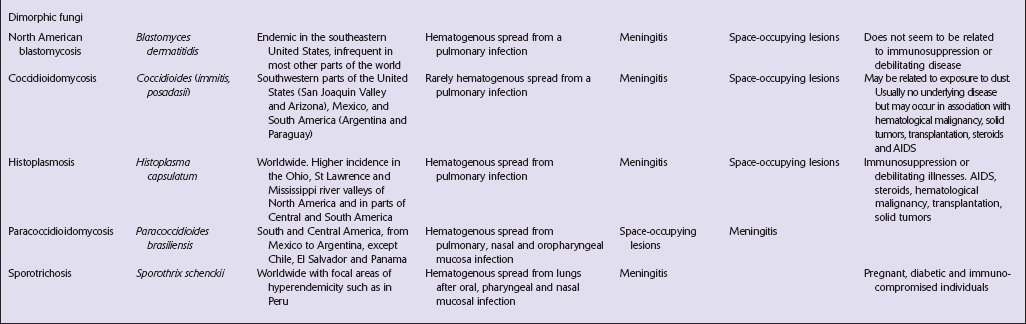

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

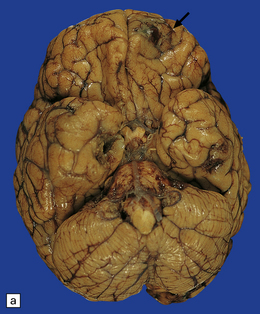

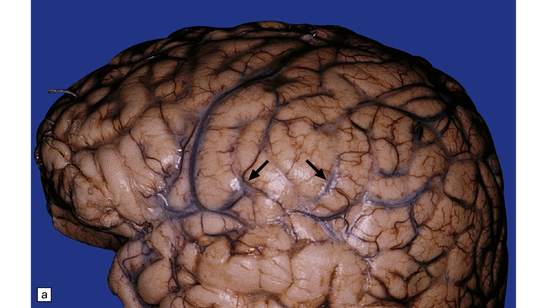

Hematogenous dissemination generally leads to multiple lesions, which vary from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter. These often occur in the anterior and middle cerebral artery distributions and involve the cerebral cortex (Fig. 17.1), white matter, and basal ganglia, but brain stem and cerebellar structures (Fig. 17.1) may also be affected.

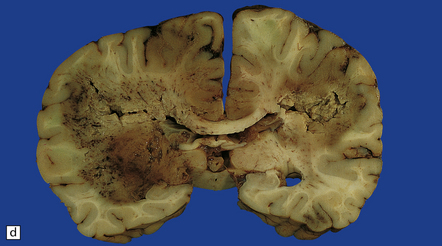

17.1 CNS aspergillosis.

(a) Scattered foci of softening and hemorrhage are visible on the external surface of the brain (arrow) from a leukemic patient with Aspergillus infection. (b) Aspergillus lesions in the cerebral cortex. The necrotic lesions (arrows) resemble foci of acute infarction. (c) Hemorrhagic Aspergillus lesions (arrows) in the cerebellum. (d) Aspergillus infection may cause extensive parenchymal necrosis. In this case large regions of cerebral necrosis are surrounded by dusky brown, hemorrhagic tissue.

Early lesions often resemble hemorrhagic infarcts (Fig. 17.1). These may form abscesses, although a thick fibrous capsule only rarely develops. In other lesions, there are foci of non-suppurative white or yellow necrotic material admixed with a variable amount of hemorrhagic tissue (Fig. 17.1). Much less frequently the fungus produces intraparenchymal granulomas or even meningitis. Aspergillus granulomas are usually a feature of chronic infection, but may be solitary lesions.

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Prominent microscopic features are:

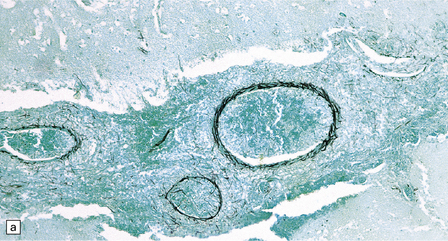

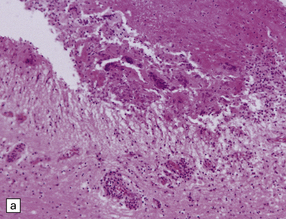

Hyphae are found in the lumen, the wall and adjacent tissue of blood vessels of varying caliber (Fig. 17.2) and may be visible as silhouette-like unstained structures in giant cells. Although they are faintly visible in hematoxylin and eosin preparations and stain with the PAS technique, the hyphae are most clearly demonstrated by methenamine silver impregnation. Because Aspergillus is morphologically similar to several other molds, a diagnosis of ‘invasive septate hyphae consistent with aspergillosis’ is the most accurate diagnosis that can be given on histopathology alone.

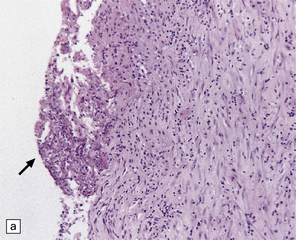

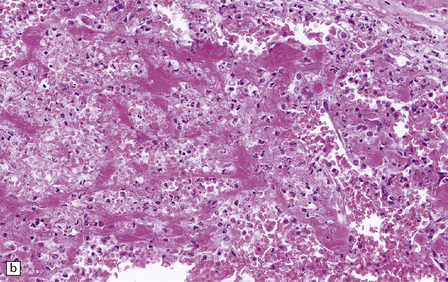

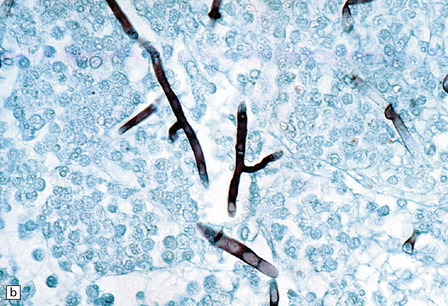

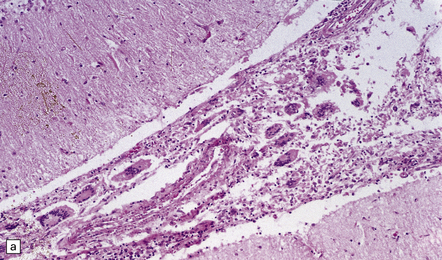

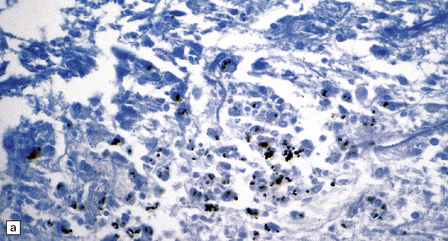

17.2 Aspergillus invasion of blood vessels.

(a) Extensive infiltration of the walls of leptomeningeal blood vessels by Aspergillus hyphae. (b) Vascular invasion by Aspergillus admixed with thrombus in the lumen, infiltrating the vessel wall and extending into adjacent tissue. (c) Aspergillus hyphae in the wall of an artery. Numerous hyphae are also visible within the adjacent inflammatory infiltrate that consists largely of macrophages. (d) Spread of infection along small parenchymal blood vessels.

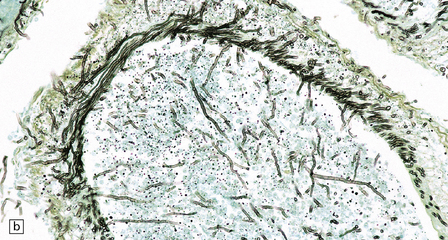

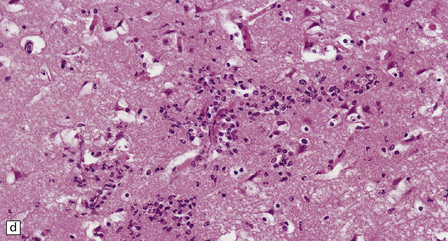

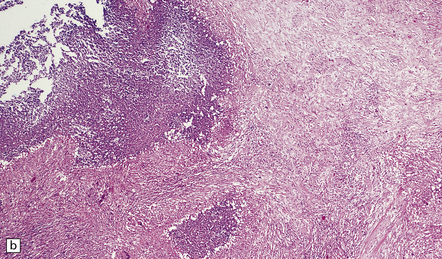

Neutrophils predominate in the early phase of disease and macrophages at later stages. In abscesses, frank pus can be seen in the center of the lesion and abundant neutrophil infiltration at the edges, in some cases accompanied by granulomas. Necrotizing non-suppurative lesions include zones of coagulative necrosis with scanty neutrophil reaction and hemorrhage. Both types of acute lesion are associated with vasculitis, vascular necrosis, and thrombosis (Fig. 17.3).

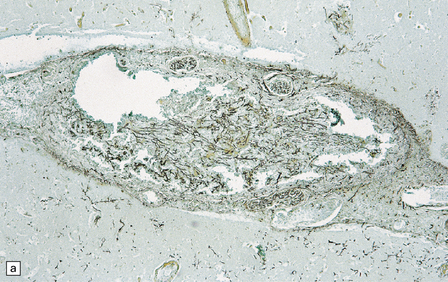

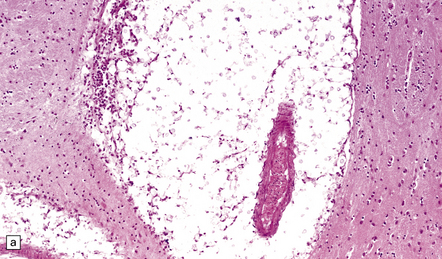

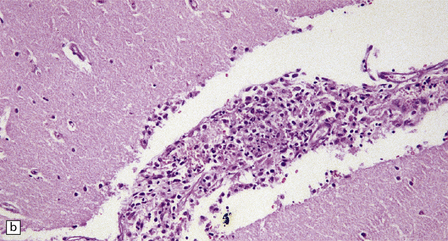

17.3 Arterial thrombosis in aspergillosis.

Inflammation, thrombosis and extensive destruction of a branch of the middle cerebral artery that had been infiltrated by Aspergillus.

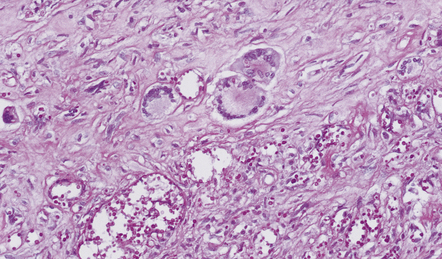

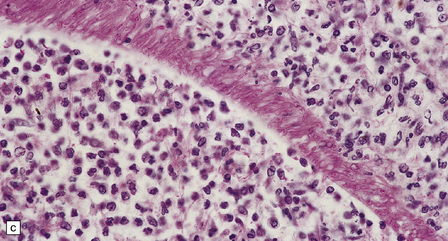

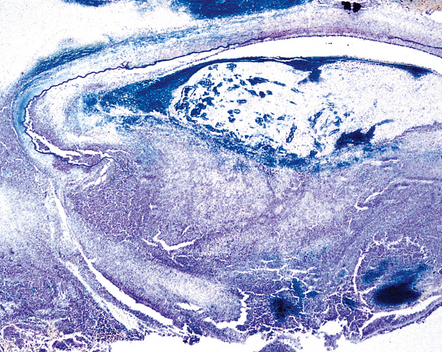

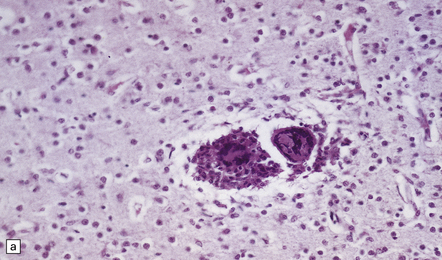

Granulomatous lesions consist of aggregates of lymphocytes, plasma cells, epithelioid macrophages, Langhans-type multinucleated giant cells, and variable amounts of collagen and necrotic tissue (Fig. 17.4). Chronic granulomas may become densely fibrotic.

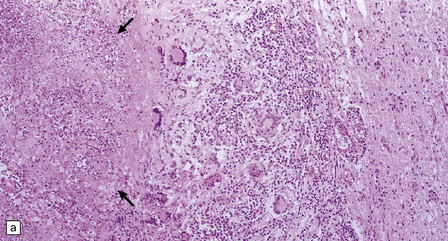

17.4 Granulomatous inflammation in aspergillosis.

(a) and (b) show granulomatous periventricular and intraventricular inflammation due to Aspergillus. The inflammatory infiltrate includes multinucleated giant cells.

Chronic abscesses may develop a dense collagenous connective tissue capsule (Fig. 17.5) without a granulomatous tissue reaction. The amount of inflammation varies from patient to patient and may be scanty in treated cases.

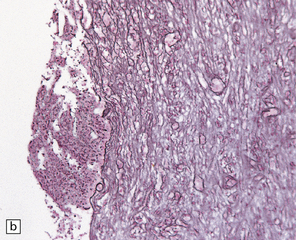

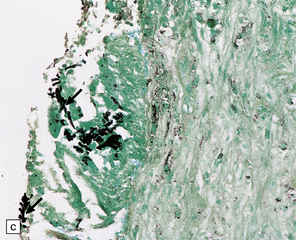

17.5 Adjacent sections through a chronic Aspergillus abscess.

(a) The abscess cavity contains necrotic debris (arrow). The wall consists of multiple layers of fibroblasts and collagen, and contains scattered lymphocytes and macrophages. (b) Abundant intercellular reticulin in the abscess wall. (c) Fungal hyphae (arrows) can be demonstrated amongst the necrotic debris within the abscess cavity.

MUCORMYCOSIS/ZYGOMYCOSIS

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

In rhinocerebral mucormycosis, foci of hemorrhagic necrosis are most prominent in the orbital part of the frontal lobes (Fig. 17.6). Necrotic, hemorrhagic tissue is present in the nasopharynx, orbit, and adjacent skull base. There may be thrombosis in the cavernous sinus or carotid artery. When CNS involvement results from hematogenous dissemination, lesions tend to be concentrated in the basal ganglia.

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

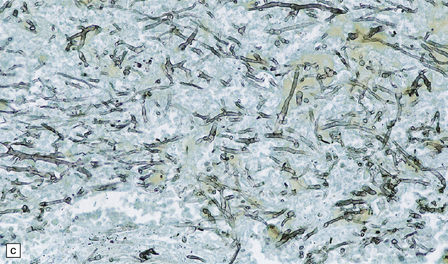

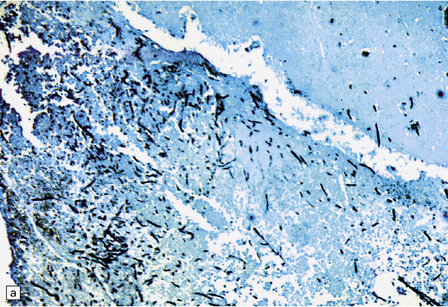

The diagnostic broad non-septate hyphae vary in caliber and branch at irregular intervals. They can be seen in and around the walls of blood vessels in the meninges and brain (Fig. 17.7). Admixed hyphae and thrombus occlude the lumina and are associated with extensive hemorrhagic infarction (Fig. 17.7). The hyphae, which may be relatively sparse, are best demonstrated by methenamine silver impregnation. A mixed or predominantly neutrophil inflammatory response may occur around the infiltrated blood vessels and where hyphae extend into adjacent brain tissue. Multinucleated giant cells are occasionally seen, but granulomas are not a typical feature.

17.7 Rhinocerebral mucormycosis.

(a) Thrombosed artery in which thrombus is admixed with fungal hyphae. Hyphae are also present in the adjacent necrotic brain tissue. (b) Higher magnification reveals broad irregular hyphae admixed with fibrin and macrophages. (c) Methenamine silver impregnation shows the hyphae to be broad, non-septate and of varying calibre. (d) The adjacent frontal cortex and white matter were extensively infarcted. This section includes the edge of the region of infarction, and shows small foci of hemorrhage in the white matter.

FUSARIUM Infection

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Disseminated infection can cause meningitis and brain abscesses, with an associated mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltrate. Microglial nodules may be widely scattered throughout the brain. The fungus tends to invade blood vessels, causing thrombosis and tissue necrosis. The septate, broad, branching hyphae are well visualized by silver impregnation (Fig. 17.8). Differentiation from other hyalohyphomycoses such as Aspergillus requires culture.

17.8 Fusarium meningoencephalitis.

(a) Cerebral abscess in an immunocompromised patient with disseminated infection. Methenamine silver impregnation reveals numerous fungal hyphae. (b) Higher magnification shows the hyphae to be septate and of varying caliber, although mostly quite broad. (Courtesy of Dr F Soares, Cancer Hospital, Sáo Paulo, Brazil.)

PHAEOHYPHOMYCOSIS

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

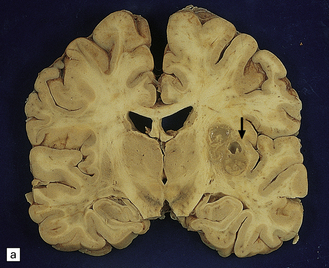

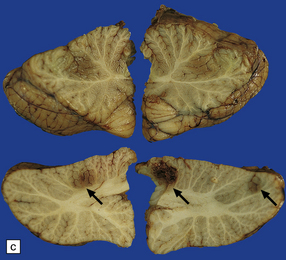

The frontal lobe is most often involved, but lesions can occur anywhere in the brain. Foci of infarction and necrosis occur, may cavitate and become encapsulated to form single or multiple abscesses (Fig. 17.9). These may extend into the subarachnoid space or ventricles, producing leptomeningitis or ventriculitis. The characteristic brown color of the mycelia can be recognized macroscopically.

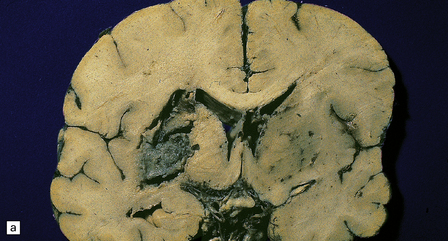

17.9 CNS phaeohyphomycosis caused by C. trichoides (cladosporidiosis).

(a) A coronal section through the cerebral hemispheres shows a large focus of necrosis in the left basal ganglia. The brown discoloration of the material within the abscess is partly due to the pigmentation of the fungi. There is also infarction and dusky discoloration of the right basal ganglia and insula. (b) The brown pigmentation of the fungal hyphae and conidia is clearly visible in this tissue section. (c) Mononuclear inflammation and early encapsulation at the edge of the abscess. (d) The hyphae and elliptical conidia are well demonstrated by methenamine silver impregnation. (Courtesy of Dr Luciano Queiroz.)

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Histology reveals infarcts and parenchymal abscesses. There may be a chronic meningitis and ventriculitis. The abscesses contain necrotic debris and branching fungal hyphae with prominent round or elliptical conidia (Fig. 17.9). Both the conidia and the hyphae are pigmented, and can be seen in unstained sections. They are also well visualized with PAS, or methenamine silver impregnation. The parenchymal inflammatory reaction varies. In some cases the necrotic tissue and fungi are surrounded by neutrophils, lymphocytes, histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells, and there is prominent fibrosis and reactive gliosis. In other cases the reaction may be minimal.

YEASTS

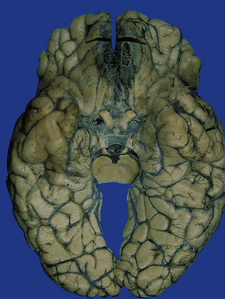

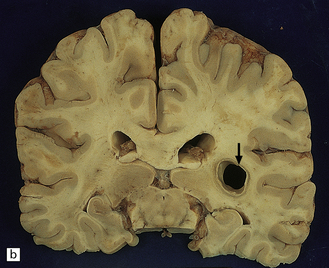

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

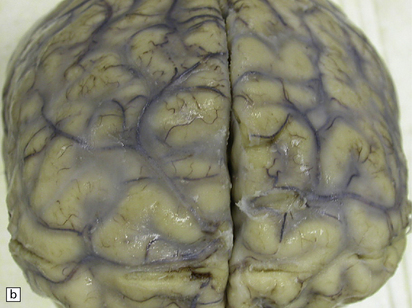

Macroscopic changes may be minimal. However, in most cases the meninges are moderately thickened and opacified (Fig. 17.10). In cases of particularly florid infection, the large number of organisms gives the surface of the specimen a slimy consistency. Rarely, small granulomas 2–3 mm in diameter and similar to those of tuberculous meningitis are seen (Fig. 17.10). In some patients with AIDS, there is a yellow–gray exudate in the ventricles and perivascular spaces as well as in the leptomeninges.

17.10 Examples of cryptococcal meningitis.

(a) and (b) The meninges are thickened particularly over the sulci. A few small granulomas are visible in (a) (arrows).

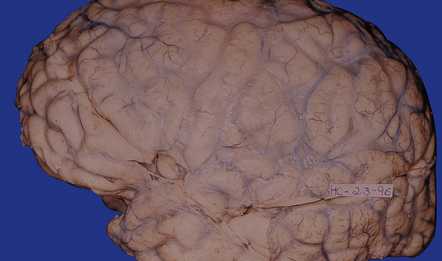

Subacute or chronic cryptococcal meningitis produces leptomeningeal fibrosis (Fig. 17.11) and is often associated with hydrocephalus (Fig. 17.12).

17.11 Chronic cryptococcal meningitis.

Markedly fibrotic leptomeninges in chronic cryptococcal meningitis.

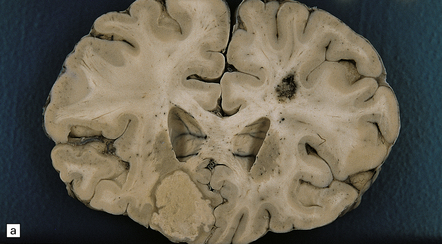

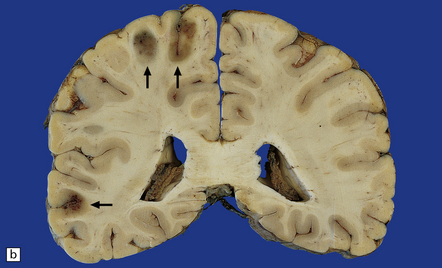

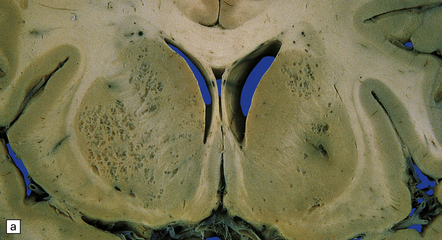

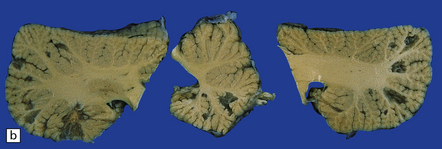

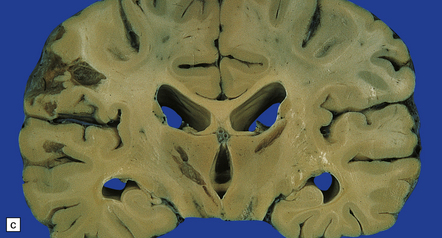

17.12 Cryptococcosis with multiple small cysts.

(a) In the basal ganglia; (b) cerebellum; (c) and the thalamus and cerebral cortex. Note the moderate hydrocephalus in (c).

Approximately 50% of cases show, in addition to meningeal involvement, multiple intraparenchymal cysts that have been likened to soap bubbles (Fig. 17.12). These are related to the exuberant capsular material produced by proliferating cryptococci in perivascular spaces in the gray matter. Cryptococcal cysts are often prominent in the basal ganglia. The dura mater is occasionally involved, particularly in the spinal canal.

Cryptococcomas have a variable appearance. Some are solid gelatinous (Fig. 17.13) or granulomatous lesions, while others resemble bacterial abscesses. They can occur in the meninges, parenchyma, adjacent to ependymal surfaces, or in the choroid plexus.

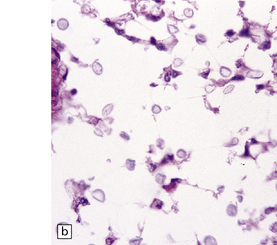

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

The organisms appear as singly budding yeast forms. They have a round body, 4–7 μm in diameter, and are surrounded by a capsule 3–5 μm thick, which stains strongly with Alcian blue or mucicarmine. The fungi can also be visualized by PAS staining or methenamine silver impregnation. Shrinkage of the capsule during paraffin embedding may leave a clear ‘halo’ around the stained organisms. The staining reactions are similar to those of corpora amylacea, with which cryptococci can be confused (Fig. 17.14).

17.14 Cryptococci in perivascular space.

(a) Enlarged perivascular space containing numerous cryptococci. (b) In sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin, cryptococci appear as spherical basophilic bodies that may resemble corpora amylacea. (c) The cryptococci are strongly PAS-positive.

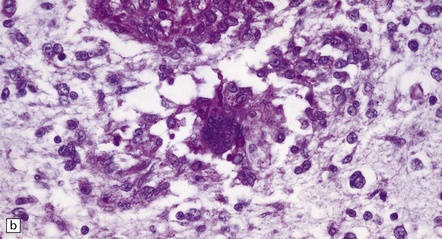

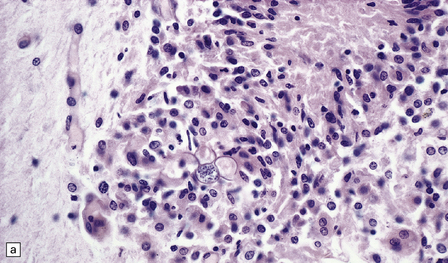

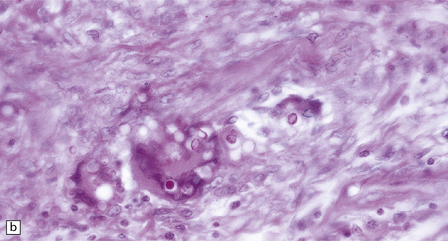

Leptomeningeal inflammation is usually scant, but can be pronounced. When present, it comprises collections of lymphocytes, plasma cells, eosinophils, and multinucleated giant cells. The nuclei of the giant cells are generally located more centrally than in Langhans-type giant cells (Fig. 17.15). Cryptococci, with or without capsules, are often visible in the cytoplasm of the giant cells (Fig. 17.15).

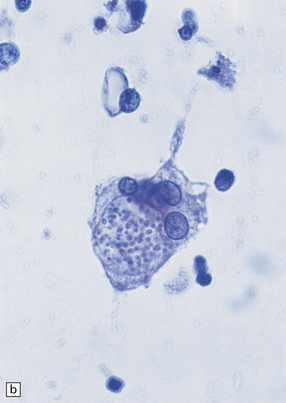

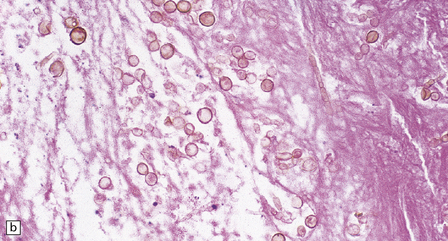

17.15 Cryptococcal meningitis.

(a) Leptomeningeal inflammatory infiltrate including several multinucleated giant cells. (b) Cryptococci in the cytoplasm of multinucleated giant cells. Note the clear halos due to shrinkage of the capsule around many of the cryptococci.

The gelatinous parenchymal lesions consist of colonies of cryptococci, which fill and expand the perivascular spaces. There is usually little or no surrounding inflammation and gliosis (Fig. 17.14).

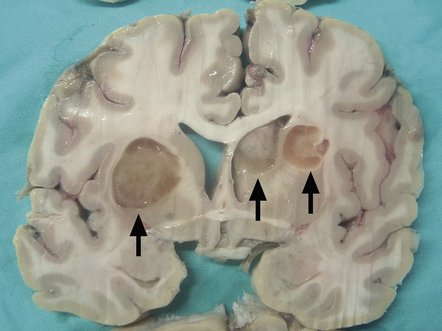

CANDIDIASIS

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

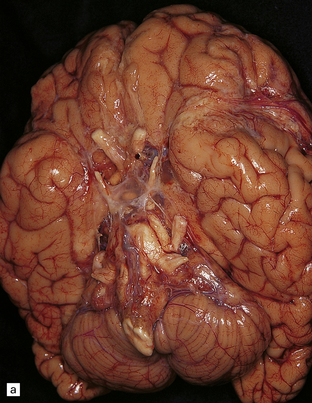

In some cases, there are no macroscopic abnormalities. The meninges usually appear normal. Scattered hemorrhagic infarcts may involve any part of the CNS, but occur most often in the perfusion territories of the anterior and middle cerebral arteries. The infarcts evolve into small abscesses (Fig. 17.17) or granulomas.

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

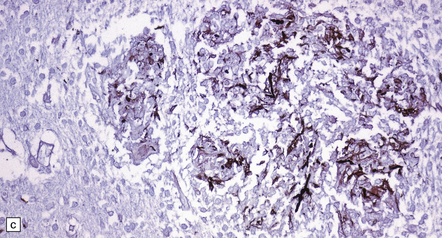

The budding yeasts and pseudohyphae are faintly basophilic in sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Fig. 17.18), stain intensely with PAS (Fig. 17.18), and are also well visualized with methenamine silver impregnation (Fig. 17.18). They are demonstrable in and around blood vessels and in and adjacent to foci of necrosis. There may be thrombosed blood vessels with adjacent hemorrhage and infarction.

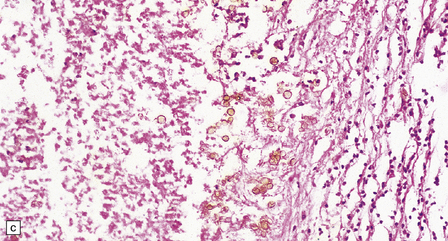

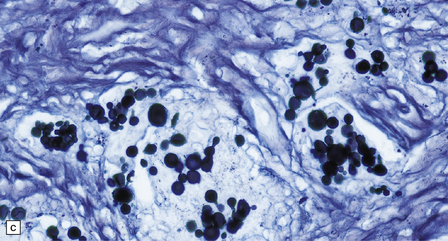

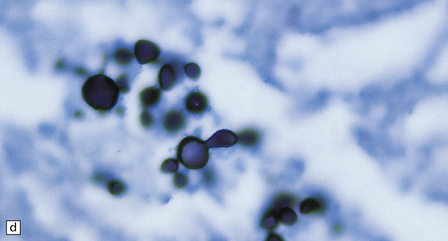

17.18 CNS candidiasis.

(a) Basophilic Candida yeasts and pseudohyphae. The surrounding brain tissue shows changes of acute infarction. (b) The yeasts stain strongly with PAS. Here they are surrounded by an infiltrate of lymphocytes and macrophages. (c) Silver methenamine impregnation of Candida fungi within a focus of granulomatous inflammation.

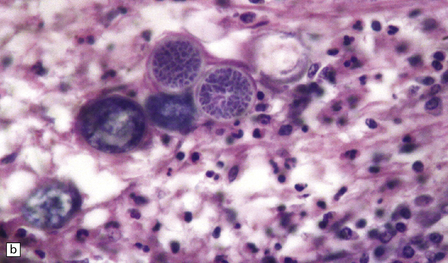

Formation of microabscesses with an accumulation of mononuclear and polymorphonuclear leukocytes.

Formation of microabscesses with an accumulation of mononuclear and polymorphonuclear leukocytes.

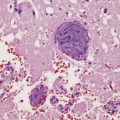

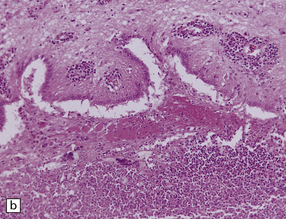

Formation of small granulomas (Fig. 17.19) associated with lymphocytes, macrophages, plasma cells, and occasional multinucleated giant cells.

Formation of small granulomas (Fig. 17.19) associated with lymphocytes, macrophages, plasma cells, and occasional multinucleated giant cells.

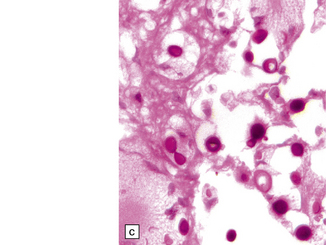

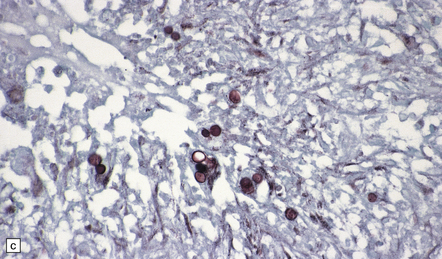

17.19 Candida granulomas.

(a) Small Candida granuloma containing multinucleated giant cells. (b) Foci of necrosis surrounded by dense fibrosis with large numbers of inflammatory cells, including multinucleated giant cells. (c) Demonstration of Candida yeasts within the granulomas by silver methenamine impregnation.

DIMORPHIC FUNGI

NORTH AMERICAN BLASTOMYCOSIS

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Although usually visible in hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections, the fungi are best demonstrated with PAS or methenamine silver impregnation (Fig. 17.20). B. dermatitidis elicits a mixed granulomatous and purulent reaction in varying combinations. Neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages surround necrotic tissue containing variable numbers of yeasts. Older abscesses develop a thick collagenous capsule (Fig. 17.20). The lesions may resemble tuberculous granulomas with central caseous necrosis and Langhans-type multinucleated giant cells.

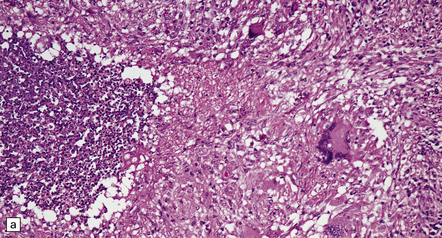

17.20 CNS blastomycosis.

(a) and (b) Blastomyces abscess cavities that contain necrotic debris and are surrounded by a granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate, with scattered multinucleated giant cells. (c) The Blastomyces yeasts are demonstrated by methenamine silver impregnation. (Courtesy of Dr Sydney Schochet, West Virginia University, USA.)

COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

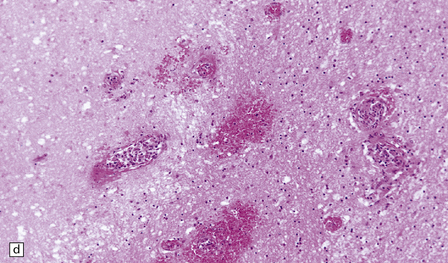

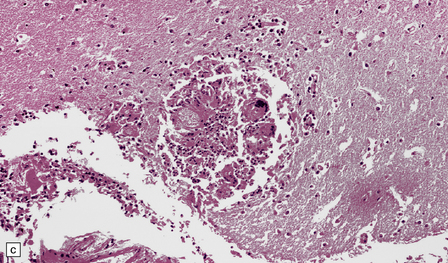

The spherules and enclosed endospores usually appear basophilic when stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Fig. 17.21), but are better demonstrated by methenamine silver impregnation. The spherules are surrounded by varying numbers of lymphocytes, plasma cells, epithelioid cells, multinucleated giant cells, and fibroblasts (Fig. 17.21). These may be aggregated to form small granulomas with central caseous necrosis. The inflammatory reaction resembles that of a tuberculous infection. On rupture of the spherules, however, the endospores tend to elicit a more acute inflammatory response with neutrophils and microabscess formation. Extension of the acute inflammation into the meninges may produce a florid but localized meningoencephalitis (Fig. 17.21).

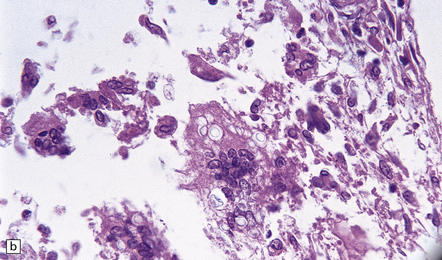

17.21 CNS coccidioidomycosis.

(a) Coccidioides spherules with enclosed endospores (arrow) are visible in a focus of granulomatous inflammation with central necrosis. (b) The morphology of the spherules and endospores is well demonstrated in this lesion. (c) Small Coccidioides granuloma with multinucleated giant cells present in the cerebral cortex. (d) Florid meningoencephalitis in a patient with coccidioidomycosis.

HISTOPLASMOSIS

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Lesions in the CNS consist of thickened leptomeninges, especially around the base of the brain, miliary granulomas, and small foci of necrosis. A yellowish gray exudate may accumulate within the cerebral sulci and basal meninges (Fig. 17.22). Basal inflammation and associated thrombosis of perforating vessels may cause infarction of the basal ganglia. The granulomas often involve the ependyma and choroid plexus.

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

The 2–5 μm yeasts are best visualized with PAS or methenamine silver impregnation (Figs 17.22, 17.23). The fungi appear much smaller on hematoxylin and eosin staining, which reveals only the basophilic yeast cytoplasm and not the surrounding cell wall. The cytoplasm tends to shrink away from the cell wall during tissue processing to produce a halo, which on cursory examination resembles a capsule.

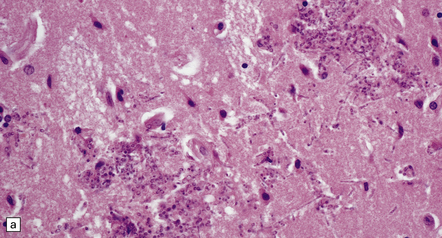

17.23 CNS histoplasmosis

(a) Histoplasma yeasts in macrophages and lying extracellularly in the brain of a patient with AIDS. (b) Inflammatory infiltrate in the meninges of a patient with CNS histoplasmosis.

Lesions range from small nodular aggregates of macrophages to classical caseating or non-caseating granulomas containing epithelioid cells and Langhans giant cells. The yeasts are usually found aggregated within the cytoplasm of macrophages (Figs 17.22, 17.23), but may be sparse.

The meningeal infiltrate (Fig. 17.23) resembles that of tuberculous meningitis, with lymphocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells, and occasional granulomas. The inflammation can extend into the walls of blood vessels, causing focal vascular necrosis and thrombosis.

PARACOCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

The more frequent form of CNS paracoccidioidomycosis is the pseudotumorous form, which results from the formation of one or more paracoccidioidomycomas. These well-circumscribed necrotic nodules vary from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter (Fig. 17.24) and are usually situated in the cerebral cortex. Similar lesions can occur in the brain stem and spinal cord. Paracoccidioidomycomas in the dura mater may simulate meningiomas both clinically and macroscopically. The leptomeningitis is granulomatous, predominantly basal, and may cause obstructive hydrocephalus.

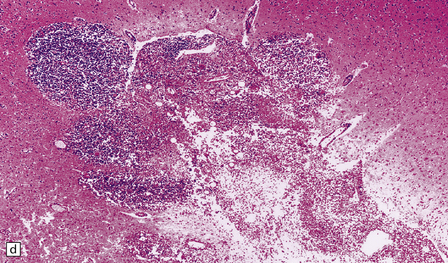

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

The granulomas are formed from lymphocytes, macrophages, epithelioid cells, and Langhans- or foreign body-type giant cells (Fig. 17.25). The granulomas may have a necrotic center and resemble tubercles, but thick-walled budding yeasts are usually demonstrable in sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin, PAS, or methenamine silver impregnation (Fig. 17.25). There may be a chronic inflammatory infiltrate in the leptomeninges. The meningeal infiltrate tends to extend along the perivascular (Virchow–Robin) space into the underlying brain parenchyma, particularly in the hypothalamus and the lateral fissures.

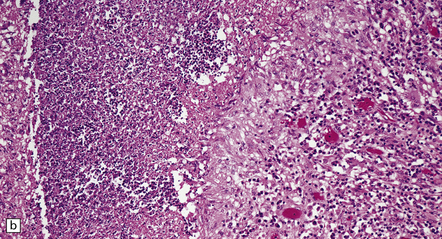

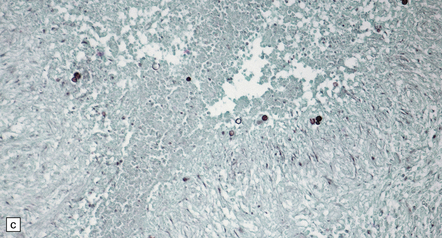

17.25 CNS paracoccidioidomycosis.

(a) Paracoccidioidomycomas with central necrosis (arrows) and surrounding inflammation, including multinucleated giant cells. (b) PAS-stained yeasts in the cytoplasm of multinucleated cells. (c) The yeasts within a paracoccidioidomycoma are well demonstrated by methenamine silver impregnation. (d) High magnification view of budding Paracoccidioides yeasts.

REFERENCES

Chakrabarti, A. Epidemiology of central nervous system mycoses. Neurol India.. 2007;55:191–197.

Chimelli, L., Mahler-Araujo, M.B. Fungal infections. Brain Pathol.. 1997;7:613–627.

Davis, L.E. Fungal infections of the central nervous system. Neurol Clin.. 1999;17:761–781.

de Medeiros, B.C., de Medeiros, C.R., Werner, B., et al. Central nervous system infections following bone marrow transplantation: an autopsy report of 27 cases. J Hematother Stem Cell Res.. 2000;9:535–540.

Gottfredsson, M., Perfect, J.R. Fungal meningitis. Semin Neurol.. 2000;20:307–322.

Marra, C.M. Bacterial and fungal brain infections in AIDS. Semin Neurol.. 1999;19:177–184.

Raparia, K., Powell, S.Z., Cernoch, P., et al. Cerebral mycosis: 7-year retrospective series in a tertiary center. Neuropathology.. 2010;30:218–223.

Rauchway, A.C., Husain, S., Selhorst, J.B. Neurologic presentations of fungal infections. Neurol Clin.. 2010;28:293–309.

Shankar, S.K., Mahadevan, A., Sundaram, C., et al. Pathobiology of fungal infections of the central nervous system with special reference to the Indian scenario. Neurol India.. 2007;55:198–215.

Sundaram, C., Umabala, P., Laxmi, V., et al. Pathology of fungal infections of the central nervous system: 17 years’ experience from Southern India. Histopathology.. 2006;49:396–405.

Elinav, H., Zimhony, O., Cohen, M.J., et al. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis in patients without predisposing medical conditions: a review of the literature. Clin Microbiol Infect.. 2009;15:693–697.

Hussain, S., Salahuddin, N., Ahmad, I., et al. Rhinocerebral invasive mycosis: occurrence in immunocompetent individuals. Eur J Radiol.. 1995;20:151–155.

Kantarcioglu, A.S., de Hoog, G.S. Infections of the central nervous system by melanized fungi: a review of cases presented between 1999 and 2004. Mycoses.. 2004;47:4–13.

Revankar, S.G., Sutton, D.A., Rinaldi, M.G. Primary central nervous system phaeohyphomycosis: a review of 101 cases. Clin Infect Dis.. 2004;38:206–216.

Revankar, S.G., Sutton, D.A. Melanized fungi in human disease. Clin Microbiol Rev.. 2010;23:884–928.

Revankar, S.G. Phaeohyphomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am.. 2006;20:609–620.

Shamim, M.S., Enam, S.A., Ali, R., et al. Craniocerebral aspergillosis: a review of advances in diagnosis and management. J Pak Med Assoc.. 2010;60:573–579.

Skiada, A., Vrana, L., Polychronopoulou, H., et al. Disseminated zygomycosis with involvement of the central nervous system. Clin Microbiol Infect.. 2009;15:S46–S49.

Davis, J.A., Horn, D.L., Marr, K.A., et al. Central nervous system involvement in cryptococcal infection in individuals after solid organ transplantation or with AIDS. Transpl Infect Dis.. 2009;11:432–437.

Graciela Agar, C.H., Orozco Rosalba, V., Macias Ivan, C., et al. Cryptococcal choroid plexitis an uncommon fungal disease. Case report and review. Can J Neurol Sci.. 2009;36:117–122.