Chapter 3. Family Assessment

The assessment guidelines outlined in this chapter are adapted from those outlined by Wright and Leahey (2000) in the Calgary Family Assessment Model (CFAM) and reflect its strongly supported systems approach to family care.

Rationale

The family should be viewed as interacting, complex elements. The decisions and activities of one family member affect the others, and the family has an impact on the individual. Understanding family members’ interactions and communications, family norms and expectations, how decisions are made, and how the family balances individual and family needs enables the nurse to understand the family’s responses and needs during times of stress and well-being. This understanding can enrich the relationship between the nurse and family. The nurse’s positive, proactive responses to family concerns and capabilities can help the family promote the development and well-being of its members.

General Concepts Related to Assessment

The primary premise in family systems assessment is that individuals are best understood in the context of their families. Studying a child and a parent as separate units does not constitute family assessment because it neglects observation of interactions. The parents and children are part of subsystems within a larger family system, which in turn is part of a larger subsystem. Changes in any one of these systems components affect the other components, a characteristic that has been likened to the impact of wind or motion on the pieces of a mobile.

The analogy of a mobile is useful for considering a second concept in family systems assessment. When piece A of the mobile strikes piece B, piece B might rebound and strike piece A with increased energy. Piece A affects piece B and piece B affects piece A. Circular causality assumes that behavior is reciprocal; each family member’s behavior influences the others. If mother responds angrily to her toddler because he turned on the hot water tap while her infant was in the tub, the toddler reciprocates with a response that further influences the mother. It is important to remain open to the multiple interpretations of reality within a family, recognizing that family members might not fully realize how their behavior affects others or how others affect them.

All systems have boundaries. Knowledge of the family’s boundaries can help the nurse predict the level of social support that the family might perceive and receive. Families with rigid, closed boundaries might have few contacts with the community suprasystem and might require tremendous assistance to network appropriately for help. Conversely, families with very loose, permeable boundaries might be caught between many opinions as they seek to make health-related decisions. Members within family systems might similarly experience extremely closed or permeable boundaries. In enmeshed families, boundaries between parent and child subsystems might be blurred to the extent that children adopt inappropriate parental roles. In more rigid families, the boundaries between adult and child subsystems might be so closed that the developing child is unable to assume more mature roles.

Families attempt to maintain balances between change and stability. The crisis of illness might temporarily produce a state of great change within a family. Efforts at stability, such as emphatic attempts at maintenance of usual feeding routines during the illness of an infant, might seem paradoxical to the period of change; however, both change and stability can and do coexist in family systems. Overwhelming change or rigid equilibrium can contribute to and be symptomatic of severe family dysfunction. Sustained change usually produces a new level of balance as the family regroups and reorganizes to cope with the change.

Change and stability are integral concepts in development. Like individuals, families experience a developmental sequence, which can be divided into eight distinct stages.

Stage One: Marriage (Joining of Families)

Marriage involves the combining of families of origin as well as of individuals. The establishment of couple identity and the negotiation of new relationships with the families of origin is essential to the successful resolution of this stage. The new relationships will vary with the cultural context of the couple.

Stage Two: Families with Infants

This stage begins with the birth of the first child and involves integration of the infant into the family, design and acceptance of new roles, and maintenance of the spousal relationship. The birth of an infant brings about profound changes to the family and offers more challenges than any other stage in family development. A decrease in marital satisfaction is common during this stage, especially if the infant is ill or has a handicapping condition, and is influenced by individual characteristics of the parents, relationships within the nuclear and extended families, and division of labor.

Stage Three: Families with Preschoolers

Stage three begins when the eldest child is 3 years of age and involves socialization of the child(ren) and successful adjustment to separation by parents and child(ren).

Stage Four: Families with School-Age Children

This stage begins when the eldest child begins elementary or primary school (at about 6 years). Although all stages are perceived by some families as especially stressful, others report this as a particularly stressful stage. Tasks involve establishment of peer relationships by the children and adjustment to peer and other external influences by the parents.

Stage Five: Families with Teenagers

This stage begins when the eldest child is 13 years of age and is viewed by some as an intense period of turmoil. Stage five focuses on the increasing autonomy and individuation of the child, a return to midlife and career issues for parents, and increasing recognition by parents of their predicament as the “sandwich generation.”

Stage Six: Families as Launching Centers

Stage six begins when the first child leaves home and continues until the youngest child departs. During this time, the couple realigns the marital relationship while they and the child(ren) adjust to new roles as parents and separate adults.

Stage Seven: Middle-Age Families

Stage seven begins when the last child leaves home and continues until a parent retires. (This is often a stage for maximum contact between the marriage partners.) Successful resolution depends on development of independent interests within a newly reconstituted couple identity, inclusion of new and extended family relationships, and coming to terms with disabilities and deaths in the older generation. Within some cultures, such as the Vietnamese culture, parents might be incorporated into a multigenerational household.

Stage Eight: Aging Families

This stage begins with retirement and ends with the death of the spouses. It is marked by concern with development of retirement roles, maintenance of individual/couple relationships, aging, and preparation for death.

Tasks and Characteristics of Stepfamilies

Stepfamilies face unique challenges as they attempt to build a new family unit from members who all bring a history of relationships, expectations, and life experiences. Intense conflict can arise as marriage partners attempt to cope with instant children without the benefit of instant affection. The parents move from a fantasy stage, in which they dream of fixing everything that went wrong in previous marriages, to a reality stage in which the challenges and losses of transition are realized.

Guidelines for Communicating with Families

▪ Display a sincere sense of warmth, caring, and encouragement.

▪ Demonstrate neutrality; perceptions of partiality toward particular family members can interfere with assessment and assistance.

▪ Convey a sense of cooperation and partnership with the family.

▪ Promote participatory decision making.

▪ Promote the competencies of the family.

▪ Encourage the family’s use of natural support networks.

Assessment of the Family

Assessment of the family usually involves the entire family, except when the infant or child is too ill to participate.

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Internal Structure | |

| Use a genogram (see Chapter 2) to diagram family structure. The genogram is often useful in helping the family to clarify information related to family composition. | |

| Family Composition | |

|

Refers to everyone in the household.

Ask who is in the family.

|

Extended families and multigenerational households are common among many cultures such as Vietnamese, Chinese, and South Asians.

Clinical Alert

Losses or additions to families can result in crisis.

|

| Rank Order | |

| Refers to the arrangement of children according to age and gender. |

Family position is thought to influence relationships and even careers. Eldest children are considered more conscientious, perfectionistic; middle children are sometimes considered nonconformist, and to have many friends; and youngest children are sometimes seen as precocious, less responsible with resources, and playful.

Clinical Alert

Frequent references to rank order (“She’s the eldest”) might signify a role assignment that is uncomfortable for the individual who is involved.

The first child can be at increased risk for abuse in abusive families.

|

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Subsystems | |

|

Smaller units in the family marked by sex, role, interests, or age.

Ask if the family has special smaller groups.

|

Clinical Alert

A child acting as a parent surrogate might signify family dysfunction or abuse.

Mothers who are highly involved with their infants and who form tight subsystems with the infants can unintentionally push the father to an outside position. This can exacerbate marital dissatisfaction and conflict.

|

| Boundaries | |

|

Refers to who is part of what system or subsystem.

Need to consider if family boundaries and subsystems are closed, open, rigid, or permeable.

|

Strength of boundaries might be influenced by culture.

East Indian families, for example, tend to be close-knit and highly interdependent.

Cambodians and Laotians consider family problems very personal, private, and off limits to outsiders.

Clinical Alert

|

| Ask who the family members approach with concerns. |

A family with rigid boundaries might become distanced or disengaged from others.

Disengagement might also occur within families; these families are characterized by little intrafamilial communication and highly autonomous members.

|

| Assessment | Findings | ||

|---|---|---|---|

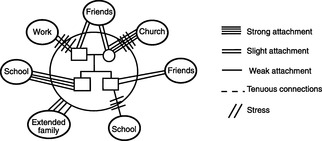

| Can be visually represented with an ecomap (Figure 3-1). | Isolation or absent or poor social networks might indicate family dysfunction. | ||

| Culture | |||

|

Way of life for a group.

Ask if other languages are spoken.

Ask how long family has lived in area/country.

Ask if family identifies with a particular ethnic group.

Ask how ethnic background influences their lifestyle.

Ask what they believe causes health/illness.

Ask what they do to prevent/treat illness.

|

The internal and external structures of a family, as well as parenting practices, are affected by ethnicity.

For example, Native

American Indians discipline through observational learning rather than through coercive control.

|

||

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Might significantly affect care. | |

| Religion | |

|

Influences family values and beliefs.

Might affect care of the infant/child.

Ask if family is involved in a church or if they identify with a particular religious group.

Ask how religion is a part of their life.

Observe for religious icons and artifacts in the home.

|

In families who are Jehovah’s Witnesses, blood transfusions are not allowed. Christian Scientists believe that healing is a religious function and oppose drugs, blood transfusions, and extensive physical examinations.

Buddhists might be reluctant to consent to treatments on holy days. Families who are Black Muslim prefer vegan diets and might refuse pork-base medicines. Islamic families might refuse narcotics and any other medicines that are deemed addictive or to have an alcohol base. Hindu families might refuse beef-based medical products.

|

| Social Class Status and Mobility | |

|

Mold family values.

Inquire about work moves, satisfaction, and aspirations.

|

Clinical Alert

Family dysfunction might be associated with job instability.

Migrancy can result in social isolation and lack of health care.

|

| Environment | |

|

Refers to home, neighborhood, and community. Ask about living arrangements (house, apartment, other?), how long in current

home. If transient, inquire about planned length of stay in community.

Refers to adequacy and safety of home, school, recreation, and transportation.

Can affect family’s ability to visit and receive ongoing care.

|

Clinical Alert

Chipped paint, heavy street traffic, uncertain water supplies, and sanitation can all affect family health.

Temporary shelters or lack of dwelling might indicate homelessness of family, related to physical or substance abuse, job layoffs, domestic conflicts, parental illness, or other crisis.

|

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Extended Family | |

|

Refers to families of origin and steprelatives.

Ask about contacts (who? frequency? significance?) with extended family members.

|

Extended family might need to be involved in care if contact is significant. In some cultures (East Indian, Iranian, Japanese), extended family might be consulted about health care decisions. |

| Family Development | |

|

Use age and school placement of oldest child to delineate stage.

Questions evolve from the developmental stage of the family. For stage two, the practitioner might inquire about the differences noticed since the birth of an infant.

|

Clinical Alert

A family that resists change might become stuck in a stage. The adolescent, for example, might be treated as a young child, producing great distress.

Family breakdown and divorce affect the family differently depending on the timing in the family cycle.

|

| Instrumental Functioning | |

|

Refers to the routine mechanics of eating, dressing, sleeping.

Inquire about concerns with accomplishment of daily tasks.

In families with young infants, inquire about how child care and household tasks are shared.

Inquire about what families would like to change related to sharing of tasks and responsibilities, if anything.

|

Clinical Alert

An ill or disabled child can significantly alter the family’s pattern of activities and ability to carry out activities.

Imbalances in the division of labor in families with young infants can be a significant source of stress and conflict.

|

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Expressive Functioning | |

| Refers to the affective issues and is useful in delineating functional families and those families who are experiencing distress and who would benefit from intervention or referral. |

Clinical Alert

A family might refuse to showemotion appropriately or allow members to do so, which can suggest dysfunction. In alcoholic families, for example, members might show an unusually bland response to extremes in circumstances or behavior.

Expression of emotions might be influenced by culture. In some cultures (e.g., Japanese), expression of emotions might be restrained.

|

| Emotional Communication | |

|

Range and type of emotions expressed in a family.

Inquire how intense emotions, such as anger and sadness, are expressed and who is most expressive.

Ask who provides comfort in the family. When something new is to be tried, who provides support?

|

Clinical Alert

Expression might be narrow, rigid, and inappropriate in dysfunctional families.

|

| Verbal Communication | |

|

Verbal communication addresses the clarity, directness, openness, and direction of communication.

Can be observed during the interview. Indirect communication can be clarified by asking questions such as, “What is your mom telling you?”

Observe congruence of verbal and nonverbal communications.

Observe if family members wait to speak until others are through.

Do parents or older siblings talk down to younger children?

|

Clinical Alert

Alcoholic and/or abusive families are frequently characterized by secrecy among family members and in relation to those outside the family. Within dysfunctional families, verbal exchanges might evidence blaming, scapegoating, or derogatory remarks. Adolescents might be exposed to public ridicule, threats related to expulsion from the family or forced encounters with police, and intense criticism.

Triangulation refers to an indirect communication pattern in which one member communicates with another through a third member.

|

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Circular Communication | |

|

Reciprocal communication that is adaptive or maladaptive.

Useful in understanding communication in dyads.

If a mother complains that her adolescent never listens to her, you might inquire: “So Susan ignores your. instruction What do you do then?”

|

|

| Problem Solving | |

|

Refers to ability of family to solve own problems.

Ask who first notices problems, how decisions are made, who makes decisions.

|

Decision making is culturally influenced. In many cultures (e.g., Hispanic, Vietnamese, Puerto Rican) the father is the main family decision maker.

Clinical Alert

Dysfunctional families might tend to employ a narrow range of strategies, consistently apply inappropriate strategies, or fail to adapt strategies to needs and stages of family members.

|

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Roles | |

|

Focuses on established behavior patterns.

Consider flexibility or rigidity of roles and whether certain idiosyncratic roles are applied to family members (“She’s always been a problem” or “He’s a good kid”).

Consider the effect of culture on roles. Ask, “In your culture what do women do? What do men do?”

Consider the influence of the multigenerational family on roles. “In your family, what did your father do? What did your mother do?”

|

Clinical Alert

Dysfunctional families might assign narrowly prescriptive roles.

|

| Control | |

|

Refers to ways of influencing the behavior of others. Might be psychologic (use of communication and feelings), corporal (hugging or spanking), or instrumental (use of reinforcers such as privileges or objects).

Inquire about family rules and what occurs when rules are broken.

Ask who enforces family rules.

Do children have a say in rules?

Consider the impact of culture on family expectations. Ask, “How are children expected to behave? What happens if they do not behave?”

|

Clinical Alert

Excessive control or chaos in relation to rules can signify an abusive family.

|

Related Nursing Diagnoses

Risk for trauma: related to neighborhood, home environment, lack of safety measures, lack of safety education, insufficient resources to purchase safety equipment or to make repairs.

Relocation stress syndrome: related to impaired psychosocial health status, losses, moderate to high degree of environment change, lack of adequate support system, feeling of powerlessness, little or no preparation for impending move.

Risk for altered growth: related to deprivation, poverty, violence, natural disasters.

Altered growth and development: related to environmental and stimulation deficiencies, inconsistent responsiveness.

Impaired home maintenance: related to family disease or injury, unfamiliarity with neighborhood resources, inadequate support systems, impaired emotional or cognitive functioning, insufficient family planning or organization.

Altered health maintenance: related to ineffective family coping, lack of material resources.

Decisional conflict: related to support system deficit, lack of experience with decision making.

Family coping, potential for growth: related to sufficient gratification of needs, effective addressing of adaptive tasks.

Ineffective family coping, compromised: related to temporary family disorganization, role changes, situational or developmental crises.

Ineffective family coping, disabling: related to highly ambivalent family relationships.

Altered family processes: related to informal or formal interaction with community, modification in family social status or finances, developmental transition or crisis, shift in health status of family member, power shift of family members.

Risk for altered parenting: related to social factors, knowledge, psychologic factors, illness.

Risk for altered parent/infant/child attachment: related to physical barriers, anxiety associated with parent role, ill child, lack of privacy, separation, inability of parents to meet personal needs.