Chapter 14. Face, Nose, and Oral Cavity

The face provides a map of the child’s emotional status and clues to neurologic, congenital, and allergic conditions. The nose provides entry to the respiratory tract, and the mouth provides entry to the digestive tract. Examination of the nose, mouth, and sinuses provides information about the functioning of the respiratory and digestive tracts and about the overall health of the child.

The common occurrence of tonsillitis provides reason enough for inspection of the oropharynx; however, examination of the nose, oral cavity, and oropharynx also yields valuable information about congenital anomalies, nutritional status, feeding practices, hydration, hygienic practices, and overall health. The information obtained can be used in the prevention, early detection, and nursing management of such disorders.

Anatomy and Physiology

The face of the newborn infant and child is noticeably different from that of the adult. Typically the neonate appears to have a slightly receding chin. By 6 years of age the mandible and maxilla have grown significantly in length and width and the chin shows greater development. A 6-year-old child has approximately 80% of the facial dimensions of the adult.

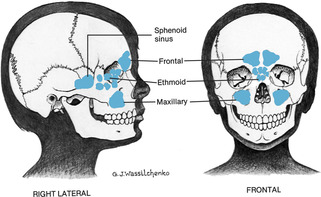

Sinuses are air pockets adjacent to the nasal passage. Only the ethmoid and maxillary sinuses are present at birth (Figure 14-1). The frontal sinus develops at around 7 years of age, and the sphenoid sinus develops in adolescence. Development of the sinuses is assisted by enlarging skull bones.

|

| Figure 14-1Location of sinuses.(From Hockenberry MJ et al: Wong’s nursing care of infants and children, ed 7, St Louis, 2003, Mosby.)Elsevier Inc. |

The nose warms, filters, and moistens air entering the respiratory tract and is the organ of smell. Infants have a narrow bridge and are obligate nose breathers, which readily predisposes them to compromise of the upper airway. The sense of smell is poor at birth but develops with age.

The mouth of the young infant is short, smooth, and has a relatively long, soft palate. The tongue appears large in the shorter oral cavity and tends to press into the concavity of the roof of the mouth, which allows milk to flow back to the pharynx. By 6 months of age the mouth is proportioned like that of the adult. Until approximately 4 months of age the infant demonstrates an active tongue thrust, or extrusion reflex, in which the tongue is pressed under the nipple. This reflex is of concern to some parents, who think that the infant is rejecting solid foods by thrusting them out as soon as they are placed on the tongue. By approximately 6 months of age the rhythmic up-and-down sucking motions of the tongue become the more adult forward-backward tongue movement. The rooting reflex, in which the infant turns the mouth in the direction that the cheek is touched, assists in food attainment and is seen in the infant younger than 3 or 4 months.

Typically the infant of 3 months begins to drool as salivation increases. The increased saliva production, together with an inappropriate swallowing reflex and lack of lower teeth, allows saliva to flow outward.

The sense of taste is immature at birth but becomes acute by 2 to 3 months as taste buds mature; however, the sense of taste is not fully functional until approximately 2 years of age, as evidenced by the strange things that young children ingest.

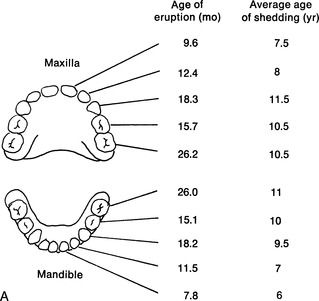

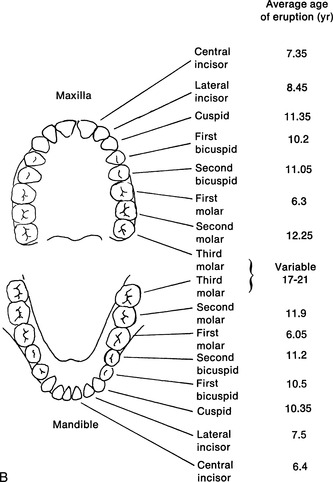

In newborn infants the gingivae (gums) are smooth, with a raised fringe of tissue along the gum line. Pearlike areas might be seen along the gingivae. These are often mistaken for teeth but are retention cysts and disappear in 1 to 2 months. True dentition begins at approximately 6 months of age, when the lower central incisors appear. By 30 months the child has 20 teeth and primary dentition is complete (Figure 14-1). During middle childhood the permanent molars erupt and the primary teeth are lost. The typical 6 year old appears toothless because of the loss of the middle teeth. Tooth eruptions and losses are genetically predetermined.

|

|

| Figure 14-2Primary and secondary dentition. A, Sequence of eruption and shedding of teeth. B, Sequence of eruption of secondary teeth.(From Wong DL: Whaley & Wong’s essentials of pediatric nursing, ed 4, St Louis, 1993, Mosby.)Elsevier Inc. |

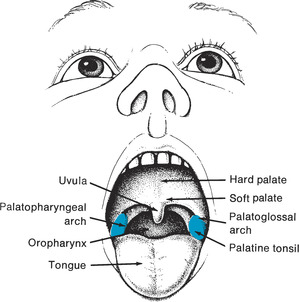

Tonsils are found in the pharyngeal cavity and are part of the lymphatic system. Several pairs of tonsils make up Waldeyer’s tonsillar ring, which encircles the pharynx; but only the palatine, or faucial, tonsil is readily visible behind the faucial pillars in the oropharynx (Figure 14-3). The pharyngeal tonsils and adenoids are located on the posterior wall of the oropharynx. Although tonsillar tissue begins to shrink by approximately 7 years of age, the child normally has larger tonsils and adenoids than either the adolescent or adult.

|

| Figure 14-3Interior structures of mouth.(From Hockenberry MJ et al: Wong’s nursing care of infants and children, ed 7, St Louis, 2003, Mosby.)Elsevier Inc. |

▪ Tongue blade (flavored, if available)

▪ Penlight

▪ Glove

Preparation

Inquire whether the child is a mouth breather or has or has had frequent sore throats; epistaxis; allergies; hay fever; fever; difficulty swallowing; vocal changes (e.g., hoarseness, nasality); or recent contact with persons with communicable disease. Ask about oral hygiene practices and date of last dental visit (if 1 year or older). Ask if the child is receiving medications.

Infants and children find examination of the mouth intrusive, and it is best left until the end of the examination. The nurse often has an opportunity to visualize the oral cavity without a tongue blade when the infant or child cries, laughs, or yawns. Infants and young children are often more comfortable on the parent’s lap during this part of the examination and can be reclined slightly for a better view. Letting the child examine the parent’s mouth or that of a puppet can assist in relieving apprehension about the examination. Having the child tilt the head slightly and breathe deeply can eliminate the need for use of the tongue blade as this will lower the tongue to the floor of the mouth. Infants and young children might need restraining.

Assessment of Face and Nose

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Observe the spacing and size of facial features. | Infants who were premature might have a narrow forehead. |

| Clinical Alert | |

| Coarse features combined with a low hairline and large tongue can indicate cretinism. | |

| An enlarged forehead can indicate hydrocephalus or ectodermal dysplasia. |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| A long, narrow face with prominent jaw can suggest fragile X syndrome, especially if there are developmental and language delays. | |

| A flat midface, thin upper lip, smooth philtrum, and micrognathia can be suggestive of fetal alcohol syndrome. | |

| Carefully observe the facial expression, especially around the eyes and mouth. | Clinical Alert |

| A child with a persistently sad and forlorn expression might be abused, particularly if bruises can be detected on the body. | |

| A child who demonstrates an open mouth and facial contortions might be suffering from allergic rhinitis. | |

| Shadows under the eyes can indicate fatigue or allergy. | |

| Observe the symmetry of the nasolabial folds as the child cries and smiles. | Normal nasolabial folds are symmetric. |

| Clinical Alert | |

| Asymmetry of the nasolabial folds can indicate facial nerve impairment or Bell’s palsy. | |

| Tilt the head backward and push the tip of the nose upward to visualize the internal nasal cavity. Use a penlight for better illumination. Observe the integrity, color, and consistency of the mucosa, the position of the septum, and for perforation of the septum. Perforation will be indicated by light showing through the perforation to the other nostril. | The nasal mucosa should be firm and pink. |

| Clinical Alert | |

| A pale, boggy nasal mucosa, with or without pink-grape polyps, indicates allergic rhinitis. A red mucosa indicates infection. | |

| Excoriation of the nasal mucosa can indicate nose picking, a common cause of epistaxis in children, or cocaine or amphetamine use. |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Usually inspection without a speculum is adequate; however, if closer examination is warranted, a short-barreled speculum, attached to the otoscope, can be used. Explain beforehand what will happen and insert the speculum into the nasal passageway, avoiding the septum. Tilt the otoscope upward to straighten the passageway toward the posterior wall. | Grayish soft outgrowths of mucosa are polyps that can partially obstruct the nares. |

| Report any deviation of the nasal septum. | |

| Diminished nasal hair can suggest cocaine or amphetamine use. | |

| Observe the size and shape of the nose. Draw an imaginary line down the center of the face between the eyes and down the notch of the upper lip. | The nose should be symmetric and in the center of the face. A flattened bridge is sometimes seen in Asian and black children. |

| Clinical Alert | |

| A flattened nose can indicate congenital anomalies and should be reported. | |

| Fissures associated with cleft lip can extend to the nostril and involve one or both nostrils. | |

| Clinical Alert | |

| Observe the external nares for flaring, discharge, excoriation, and odor. | Flaring external nares can indicate respiratory distress or crying. |

| The skin of the external nares should be intact. No discharge should be seen, although a clear, watery discharge might be present if the child has been crying. |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Excoriation of the external nares can indicate the presence of an irritating discharge and frequent nose wiping. | |

| A clear, thin, nasal discharge is often present with allergic rhinitis. Purulent yellow or green discharge accompanies infection. | |

| Clear nasal discharge that tests positive for glucose after a head injury or dental or nose surgery can suggest leakage of spinal fluid. | |

| A foul odor and discharge from one nostril can indicate the presence of a foreign body. | |

| Test the patency of the nares by placing the diaphragm of the stethoscope under one nostril while blocking the other. A film appears on the diaphragm if the naris is patent. While assessing patency, the sense of smell can also be assessed. While each nostril is blocked, ask the child to close his or her eyes and to identify distinctive odors such as coffee and lemon. The child should be able to correctly identify each. | Both nares should be patent. |

| Clinical Alert | |

| Diminished smell can indicate olfactory nerve impairment or upper respiratory infection. | |

| Occlusion of the nostrils can indicate upper respiratory infection, presence of a foreign body, deviated septum, allergies, or nasal polyps. | |

| Palpate above the eyebrows and on each side of the nose to determine whether pain and tenderness are present. | Clinical Alert |

| Pain and tenderness in these regions can indicate sinusitis. |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Inspect the lips for color, symmetry, moisture, swelling, sores, and fissures. | The lips should be intact, pink, and firm. |

| Clinical Alert | |

| Blueness of the lips is a reliable sign of cyanosis in fair-skinned children; ashen coloration can indicate cyanosis in dark-skinned children. | |

| Deep red coloration can be present during an asthmatic attack. | |

| Pallor can indicate anemia. | |

| Cherry red coloration is seen with acidosis. | |

| Cracked lips are usually the result of harsh climate, lip biting, mouth breathing, or fever. | |

| Fissures at the corners of the mouth can indicate deficiency of riboflavin or niacin. | |

| Notching of the vermillion border of the lip indicates cleft lip. | |

| Drooping of one side of the lips indicates facial nerve impairment. | |

| A thin upper lip and long philtrum can suggest fetal alcohol syndrome, if other features of the syndrome are present. | |

| Inspect the buccal margins, gingivae, tongue, and palate for moisture, color, intactness, and bleeding. | The oral membranes are normally pink, firm, smooth, and moist. |

| The buccal cavity, tongue margins, and gums appear bluish in black children. |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| To inspect the buccal mucosa, ask the child to use his or her fingers to move the outer lip and cheek to one side. With toddlers and infants, it is necessary to use a tongue blade, unless a good view is possible while the child is crying. When using the tongue blade, slide it along the side of the tongue. | Clinical Alert |

| Clefts or notches in the hard or soft palate should be noted. | |

| An abnormally high, narrow arch can cause problems with sucking in the infant and with speech in the older child. | |

| White ulcerated sores on the oral mucosa are cankers, related to mild trauma, viral infection, or local irritants. | |

| Saltlike areas rimmed with red and found on the inner cheek opposite the second molar are Koplik’s spots and indicate the onset of measles. | |

| Use a glove and penlight for clearer visualization of any suspected abnormalities. | |

| White curdy patches on the gum margins, inner cheeks, tongue, or palate usually indicate thrush (oral moniliasis). | |

| Observe for the presence of odor or halitosis. | Thrush is common in infants (particularly during or following antibiotic therapy), but in children could indicate a deficient immune system disorder such as AIDS or HIV infection. These patches can be distinguished from milk curds in that they cannot be easily scraped away. |

| Petechiae on oral mucous membranes can indicate presence of emboli, accidental biting, or infection. | |

| Hyperplasic gum tissue can be related to anticonvulsant therapy. |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Reddened, swollen, bleeding gums can indicate infection, poor nutrition, or poor oral hygiene. | |

| A red tongue is related to vitamin deficiencies and to scarlet fever (“strawberry tongue”). | |

| A gray, furrowed tongue can be normal or can indicate drug ingestion, allergy, or fever. | |

| Odor or halitosis can indicate poor oral hygiene, tooth decay, constipation, dehydration, sinusitis, food trapped in tonsillar crypts, diabetic ketoacidosis or other systemic illness. | |

| Drooling accompanied by fever and respiratory distress is indicative of epiglottitis. | |

| Dry, sticky mucous membranes suggest dehydration or mouth breathing. | |

| Inspect the tongue for movement and size. | The frenulum attaches to the undersurface of the tongue or near its tip, allowing the child to reach the areolar ridge with the tip of the tongue. |

| The older child can be asked to reach the tip of the tongue to the roof of the mouth. | |

| Clinical Alert | |

| Observe the movement of the tongue in infants and younger children as they vocalize or cry. | Inability to touch the tongue to the areolar ridge can signify tongue tie and later speech problems. |

| Glossoptosis, or tongue protrusion, is seen in mental retardation and cerebral palsy. |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Inspect the teeth for number, type, condition, and occlusion. To estimate the number of teeth that should be present in a child 2 years of age or younger, subtract 6 months from the child’s age in months. Ask the child who is 5 years or older if teeth are loose. To assess malocclusion, ask the child to bite teeth together. | A normal 30-month-old child has 20 temporary teeth. A child with full permanent dentition has 32 teeth. The upper teeth should slightly override the lower teeth. |

| Clinical Alert | |

| Brown and black spots usually indicate caries. Mottling can indicate excessive fluoride intake. Green and black staining can accompany oral iron intake. | |

| Observe for fillings and braces. | |

| Extensive decay of the maxillary or upper incisors and molars in infants and young children suggests bottle or nursing caries. | |

| An increase in dental caries in adolescents can indicate frequent, self-induced vomiting. | |

| Absent, delayed, or peg teeth can indicate ectodermal dysplasia. | |

| Protrusion of the lower teeth or marked protrusion of the upper teeth should be noted. | |

| Tonsils can be inspected in the older child by asking the child to say “Ahh” or to yawn. Asking the child to tilt the head slightly back, to breathe deeply, and to hold the breath can also aid in visualization. | Tonsils, if present, are normally the same color as the buccal mucosa. They are large in the preschool-age and young school-age child and appear larger as they move toward the uvula. Crypts might be present on their surface. |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| If the child has difficulty holding the tongue down, the tongue can be lightly depressed with the tongue blade on either side. | Clinical Alert |

| Reddened tonsils covered with white exudate suggest group A hemolytic streptococcal infection or infectious mononucleosis. | |

| Playing games and demonstrating what is expected of the child through the use of a parent or doll can be very useful. | |

| Thick, gray exudate can indicate diphtheric tonsillitis. | |

| Visualization of adenoids suggests that they are enlarged. | |

| If the nurse is unable to observe the tonsil bed while the infant or older child is crying, the tongue blade can be slid between the lips, along the side of the gum, then quickly slipped between the gums along the side of the tongue. | |

| If adenoids are visualized during gagging or saying “Ahh,” they appear as grapelike structures. | |

| Any inspection of the pharynx that involves use of the tongue blade and that might elicit the gag reflex must not be performed on a child who is suspected to have any of the croup syndromes. | |

| Observe movement of the uvula during examination of the tonsils. | The uvula remains in midline. |

| Upon gagging the uvula moves upward. | |

| Movement of the uvula can be assessed by producing a gag reflex. | Clinical Alert |

| Deviation of the uvula or absence of movement can signal involvement of the glossopharyngeal or vagus nerves. Producing the gag reflex in a child with epiglottitis could produce total obstruction. |

Related Nursing Diagnoses

Ineffective airway clearance: related to retained secretions, excessive mucus, foreign body in airway, infection, asthma, allergic airways.

Altered oral mucous membrane: related to barriers to professional care, immunosuppression, cleft lip or palate, medication side effects, trauma, NPO status, mouth breathing, malnutrition or vitamin deficiency, dehydration, infection, ineffective oral hygiene, mechanical factors, impaired salivation.

Impaired skin integrity: related to altered nutritional state, altered fluid status.

Altered dentition: related to ineffective oral hygiene, barriers to self-care, barriers to professional care, nutritional deficits, dietary habits, genetic predisposition, selected prescription drugs, premature loss of primary teeth, excessive intake of fluorides, chronic vomiting, lack of knowledge regarding dental health, bruxism.

Risk for infection: related to inadequate primary defenses, inadequate secondary defenses, malnutrition, insufficient knowledge to avoid exposure to pathogens, immunosuppression.

Impaired verbal communication: related to anatomic defect.

Impaired swallowing: related to congenital deficits, neurologic problems.

Ineffective infant feeding pattern: related to anatomic abnormality.

Sensory/perceptual alterations (gustatory, olfactory): related to altered sensory perception.

Risk for fluid volume deficit: related to deviations affecting intake.

Altered nutrition, less than body requirements: related to inability to ingest food because of biologic factors.

Altered family processes: related to shift in health status of a family member.