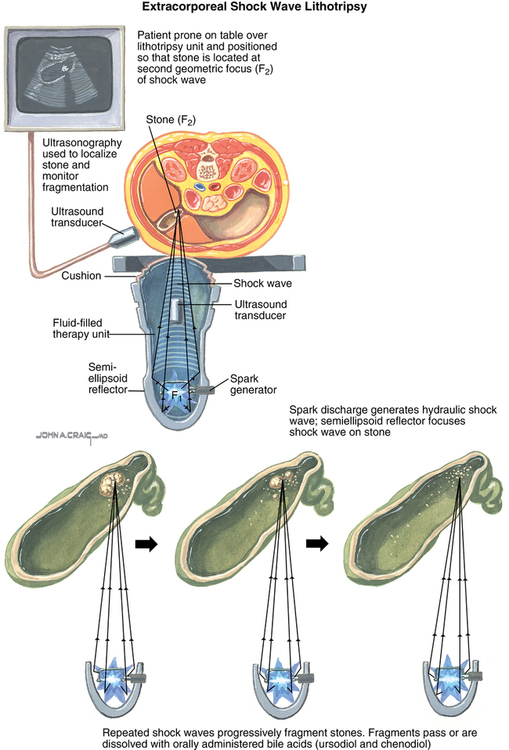

Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy

Urolithiasis is a common condition with a lifetime prevalence of 12% in the United States. It is more common in men than women and most often presents in the third to fourth decade of life. Most urinary stones can be passed spontaneously; however, 10% to 30% require urologic intervention. Since the introduction of the first lithotripter in 1980, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) (Figure 167-1) has gradually replaced open and percutaneous surgical approaches as the treatment of choice for most urinary stones requiring intervention in the kidney or upper ureter.

Patient selection

ESWL has been used successfully to manage urinary stones in infants, children, and adults. Absolute and relative contraindications to the procedure are listed in Box 167-1. Performing ESWL on patients with untreated urinary infection and urinary obstruction distal to the location of the target stone predispose the patient to the development of urosepsis. Pregnancy is considered an absolute contraindication, because the effects of shock waves on the fetus are unknown, although ESWL has been inadvertently performed on pregnant women without apparent adverse effects on the fetus. The calcified wall of an abdominal aortic aneurysm provides an acoustic interface that can result in liberation of shock-wave energy and aneurysm rupture. Various authors have recommended minimum safe aneurysm diameters (e.g., 5 to 5.5 cm) and aneurysm-to-stone distances (e.g., at least 5 cm) along with maximum voltage settings and number of shock waves that can be safely delivered. ESWL in patients who are morbidly obese can be technically challenging and have lower success rates. ESWL can be safely performed in patients with pectorally-located implanted cardiac devices (i.e., pacemakers and automated implantable cardioverter-defibrillators), provided certain conditions are met (Box 167-2). Performing ESWL in a patient with abdominally located cardiac devices is not recommended.