Examination of the Sexual Assault Victim

The majority of sexually assaulted individuals never report the crime to anyone, and only one third of sexual assaults are reported to law enforcement. In many cases, after contact with law enforcement, sexual assault victims are taken to the emergency department (ED) for evaluation, examination, and treatment. Sexual assault victims may also go to the ED without prior contact with law enforcement. In 2009, sexually assaulted patients accounted for approximately one tenth of all assault-related visits to the ED by female patients.1

Some sexual assault victims will cooperate with police investigations, but others will not. Federal legislation guarantees all victims the right to a forensic examination and treatment of sexual assault regardless of their cooperation with legal investigation or their desire to initially pursue prosecution.2 Some states require medical personnel treating sexual assault victims to report the assault to local law enforcement, whereas others forbid such reporting without patient consent. Clinicians must know their own state laws regarding such reports.

Definitions

Sexual assault refers to any sexual contact between one person and another without appropriate legal consent.3 Physical force may be used to overcome the victim’s lack of consent, but this is not mandatory to prove assault. Coercion into sexual contact by intimidation, threats, or fear also defines sexual assault. State laws differ slightly on the definition of exact acts that constitute sexual contact and on which populations are unable to give legal consent. In general, persons under the influence of drugs or alcohol, minors, and those who are mentally incapacitated are considered unable to give consent for sexual contact.

Evaluation and Treatment of Patients Suffering From Sexual Assault

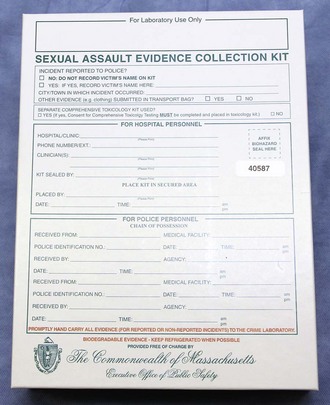

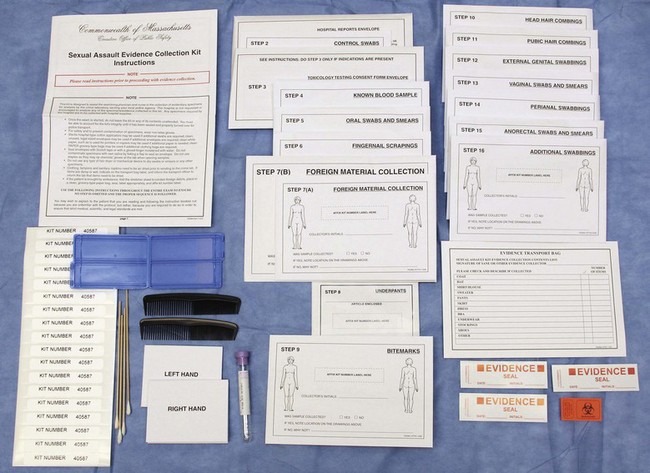

ED personnel must secure patient privacy and designate a separate area for the care of sexually assaulted patients. If medically and logistically possible, interviews should be conducted in a private room separate from the examination room. EDs often have such an area, frequently called the “grieving room” or the “family room.” Law enforcement or other governmental agencies may provide examination kits for the collection of forensic evidence from victims (Fig. 58-1). These kits should be available in the ED and the staff should be familiar with them. If such kits are not provided by local sources, hospital staff may need to assemble their own kits from material found in most EDs. Alternatively, private companies assemble and sell such kits (www.lynnpeavey.com or The Lynn Peavey Company, PO Box 14100, Lenexa, KS 66285-4100). Prepared kits save a tremendous amount of nursing and clinician time when a victim comes to the ED. A checklist of local requirements for sexual assault examination should be included in the kits and serves as a reminder for all the medicolegal procedures to be completed.

History

Elements of the victim’s history should help in deciding which potential samples to collect. For example, sperm may be recovered from the cervix for up to 12 days after intercourse and from the vagina for up to 5 days (Table 58-1).4 If the victim had voluntary intercourse 48 hours before the examination and was sexually assaulted 3 hours before the examination, obtain samples from both the vagina and the cervix and keep the two types of specimens separate. Taking a careful history makes it possible to perform an appropriate examination given these two separate events. In general, cervical swabs should be collected in addition to the usual vaginal swabs if the time between assault and examination is longer than 48 hours or if intercourse with a different person took place within a few days of the assault. Some experts advocate cervical samples in all cases that will involve speculum examination because of greater forensic yield.

TABLE 58-1

Maximal Reported Time Intervals for Sperm Recovery

| BODY CAVITY | MOTILE SPERM | NONMOTILE SPERM |

| Vagina | 6-28 hr | 14 hr-10 days |

| Cervix | 3-7 days | 7.5-19 days |

| Mouth | — | 2-31 hr |

| Rectum | — | 4-113 hr |

| Anus | — | 2-44 hr |

From Marx J, ed. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2006.

Physical Examination

General Body Examination

After the patient disrobes and is placed in a gown, examine her body for signs of trauma and foreign material. Uncover one part of the body at a time to examine and then carefully re-cover it. This allows the victim to retain some modesty during the examination. Important areas for evaluation are the back, thighs, breasts, wrists, and ankles (particularly if restraints were used). Even in the absence of ecchymosis, note tender areas during the examination. Evidence from the physical surroundings of the assault can occasionally be found in the hair or on the skin. Retain such material as evidence. Document areas of trauma and evaluate further (e.g., with radiographs) as indicated by the type and extent of injury. Approximately 10% to 67% of sexual assault victims display bodily injuries.3 Document these injuries because they correlate significantly with successful prosecution of perpetrators.5 Bodily evidence may range from abrasions to major blunt and penetrating trauma. If the victim has not bathed, bodily evidence in the form of dried semen stains may be visible on the hair or the skin of the victim. In a darkened room, dried semen (and, unfortunately, many other substances) on skin may fluoresce under examination with shortwave light, such as that produced by a Wood lamp or an alternative light source, but may also be noticed equally well by its reflective appearance under regular room lighting.6,7 Use moistened swabs to collect potential dried secretions; then air-dry them thoroughly and preserve as evidence. Fragments of the assailant’s skin, blood, facial hair, or other foreign material from the assault site may be trapped beneath a victim’s fingernails. Obtain fingernail scrapings by cleaning under a victim’s nails with a toothpick or small swab or by cutting the nails closely over a clean piece of paper. Fold the toothpick and debris into the paper, place it in an envelope, and package it with the other specimens.

Oral Evaluation

If indicated by the history, inspect the oral cavity closely for signs of trauma and collect evidence if indicated. Mouth injuries from forced oral copulation include lacerations of the labial or lingual frenulum, mucosal lacerations, and abrasions. Injury to the lips is often produced by the victim’s own teeth as her lips are forced inward by forced oral penetration with the perpetrator’s penis. Potential injuries to the posterior pharyngeal wall and soft palate include petechiae, contusions, and lacerations (Fig. 58-2). Document these injuries at the initial examination because mucosal injuries heal quickly and may not be present hours or days later. Collect potential evidence with swabs rubbed between the teeth and the buccal mucosa on both the upper and lower gingival surfaces bilaterally. Spermatozoa have been identified in oral smears for hours after the attack despite brushing the teeth, using mouthwash, or drinking various fluids and may provide valuable evidence up to 12 hours after examination.8,9 Collect any foreign material (e.g., hair) to include as potential evidence. During the oral inspection, local law enforcement may request that examiners collect buccal cell swabs to provide the crime laboratory with a sample for victim DNA reference.

Pubic Hair Samples

Significant hair transfer occurs in less than 5% of assaults.10 For the small minority of cases in which foreign suspect hairs must be compared with the victim’s hair, a sample pulled from the victim may be desired. Although pulling the patient’s hair from the roots may provide the best sample, this collection method is painful, considered insensitive, and not recommended by these authors during the initial evaluation. These hairs will rarely be needed because the vast majority of cases are never adjudicated and those that are rarely concern this type of evidence. A victim can provide the hairs at a later time, if needed, and frequently the victim is willing to pluck the hairs herself at that time.

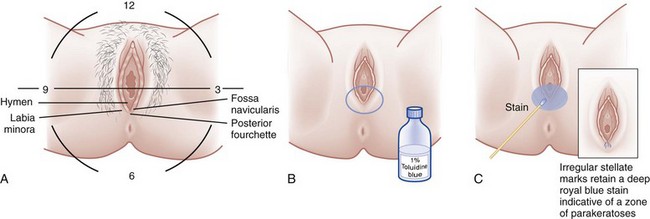

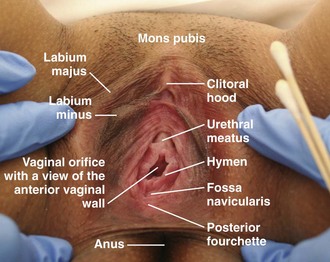

Genital examination of a sexual assault victim differs considerably from most ED pelvic examinations. First, perform a careful evaluation of the vulva and vaginal introitus for signs of trauma. The techniques of separation and traction move the tissues most likely to suffer injury into view. In performing separation, examiners use both hands to separate the labia laterally in each direction and inspect the posterior fourchette and vaginal introitus. Similarly, in performing traction, examiners use both hands to hold each labium majus and apply gentle inferior labial traction (i.e., toward the examiner); this gives a much-improved view of the hymen, especially in prepubertal females (Fig. 58-3). If the examiner fails to perform these maneuvers, traumatic genital injuries may be missed.

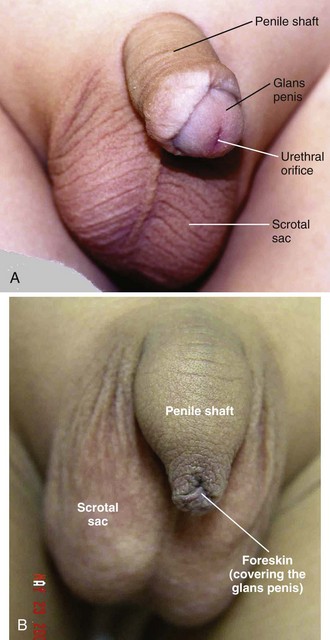

Familiarity with female (Fig. 58-4) and male (Fig. 58-5) genital anatomy, including all terms, is important for accurate descriptions. Although most novice examiners concern themselves with detecting injuries to the hymen, the majority of sexual assault–related vaginal injuries occur to the posterior fourchette (Fig. 58-6).11 In fact, hymenal injuries are rare in sexually active adult women and are more commonly observed in sexually inexperienced adolescents12,13 (Fig. 58-7). More uncommon injuries to the vaginal walls and cervix may be discovered during the speculum examination. Reported rates of genital injury in forensically examined victims range from 6% to 20% without colposcopy to 53% to 87% with colposcopy.11–13 Most importantly, examiners must be cognizant of the fact that completely normal findings on genital examination remain consistent with forced sexual assault. In fact, a study of more than 1000 sexual assault victims found that almost half of all victims with forensic evidence positive for sperm had no genital injury.14

Figure 58-4 Female anatomy.

Figure 58-5 Male anatomy. A, Circumcised. B, Uncircumcised.

Colposcopy

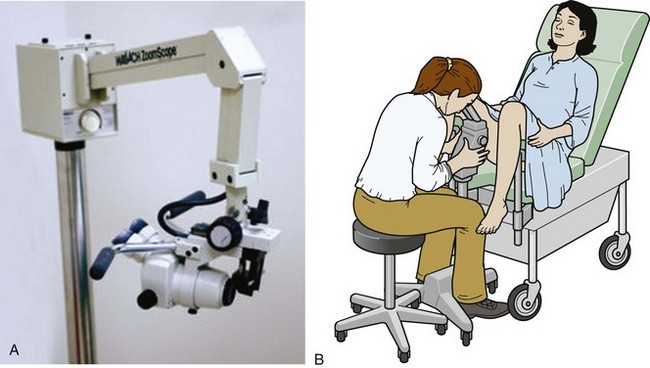

Teixeira first described the use of colposcopy for documentation of sexual assault in 1981.15 Although it is not readily available nor a standard of care in most EDs, the use of colposcopy has revolutionized the documentation of injury. The colposcope provides magnification, a bright light source, and usually permanent documentation of injuries in the form of still images or video (mainly in digital format but occasionally traditional film). In one small study the colposcope increased the rate of detection of genital injury from 6% to 53%.16 Colposcopes with photo or video attachments provide excellent photographic documentation for the court and allow review by expert practitioners for court testimony without subjecting the victim to reexamination (Fig. 58-8). Experienced sexual assault examiner programs are increasingly using high-quality digital single-lens reflex cameras mounted on a tripod to obtain excellent images that are indistinguishable from those obtained with colposcopy. ED practitioners may have access to such equipment. Colposcopically visible injuries have also been described in adolescent women after the first consensual intercourse; hence, genital injury does not always correlate with nonconsensual vaginal penetration.17 Conversely, totally normal findings on genital examination by colposcopy are often found after sexual assault. Even in sexually inexperienced adolescents, forced penetration can occur without leaving discernible genital injury.17 Although previous sexual experience by the victim decreases the likelihood of finding genital injury, experts cannot fully explain the reasons why some rape victims sustain measurable genital injury whereas others do not.

Forensic Evidence Collection

Protocols for collection of evidence vary by legal jurisdiction. Many sexual assault evaluation centers have abandoned the cumbersome kits used in the past and substituted simple collection methods that concentrate on important and usable legal evidence. The following discussion draws from the model protocol suggested by the state of California and the American College of Emergency Physicians manual.3

Obtain standard specimens during inspection of the external genitalia, rectum, vagina, and cervix. Lubricate the speculum with warm water rather than other lubricants because of the potential spermicidal activity of lubricants. However, if lubricants are inadvertently used, the potential for corruption of DNA evidence should be negligible.18 Generally, the specimens collected will be determined by victim’s history and local protocol, but they may include any of the items listed in Box 58-1 and shown in Figure 58-9. Some protocols recommend that examiners make a wet mount of one swab from the vaginal pool and look at it under the microscope for the presence of motile sperm. Because of rapid cell death, studies have shown a negligible chance of finding motile sperm from a vaginal wet mount more than 8 hours after intercourse.19 Furthermore, in complying with the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988, ED practitioners in the United States rarely have sufficient access or experience with microscopy to make this step a routine recommendation. Several swabs from the vaginal pool (including the one used to make the wet mount, if done) and the external genitalia should be obtained and then applied over clean slides for a dry mount. These slides should be allowed to air-dry and then labeled; all swabs and slides should be packaged in paper envelopes for the local crime laboratory. Some EDs maintain specific equipment (i.e., a Dry Box) to aid in the drying of specimens; in others, the swabs and slides must be left out until completely dried.

Crime laboratories may also request collection of a vaginal washing. For this procedure, insert 5 mL of sterile (but not bacteriostatic) water or saline into the vagina and then remove it. Place the washing in a sealed container (such as those used for urine collection or a red-topped blood tube). In addition, collect cervical swabs if the time from assault to examination (the postcoital interval) is longer than 48 hours or if there is a history of recent consensual intercourse as well. The crime laboratory may recover sperm from cervical specimens up to 12 days after coitus.3

Genital Testing for STDs

Guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) suggest obtaining a cervical, rectal, or oral specimen for culture or polymerase chain reaction (PCR), or both, for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. However, the majority of SART programs in the United States do not routinely perform these tests.20 STD testing during sexual assault examination can detect only infection before the assault and provides no meaningful information for the crime laboratory. In addition, routine prophylactic treatment with antibiotics effective against N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis makes detection of these preexisting infections superfluous; however, clinicians might want to consider obtaining samples for culture from child victims, in whom the presence of an STD would be indicative of previous sexual contact.

Perineal Toluidine Blue Dye Staining

Toluidine blue dye is a nuclear stain, also used for cancer detection and mast cell staining, that highlights areas of injury. It adheres to areas denuded by abrasions and lacerations where the epidermal layer of nonnucleated cells has been removed (Fig. 58-10). The underlying nucleated cells take up the dye. Although it is not a uniform standard of care and unavailable in many EDs, the dye can enhance the examiner’s ability to visualize and photographically document more subtle genital injuries (see Fig. 58-6). Genital lacerations may provide corroborating evidence of nonconsensual intercourse, or at least sexual activity. To outline injuries, apply a 1% aqueous solution of toluidine blue dye to the perineum and wipe the excess dye off with a cotton ball moistened with lubricating jelly. A swab containing the dye is commercially available. After the excess dye is removed, any areas that retain the stain signify a disruption in the epidermis, most likely injury. Separate any folds of the area and carefully examine them to avoid missing injuries. Ideally, apply the dye before speculum examination to eliminate the possibility of iatrogenic injury. The procedure is described in Figure 58-10 and Box 58-2. In one study, use of toluidine blue dye increased the injury detection rate from 16% to 40% in women without the use of colposcopy21; however, injuries detected with the aid of toluidine blue dye are not 100% specific for sexual assault because such injuries have also been found after consensual intercourse, especially in adolescents.22

Collect external genital samples before the application of toluidine blue to avoid washing away potential DNA evidence. The use of toluidine blue dye itself does not interfere with DNA evidence from vaginal specimens, and it has proved safe for mucosal application.23–25

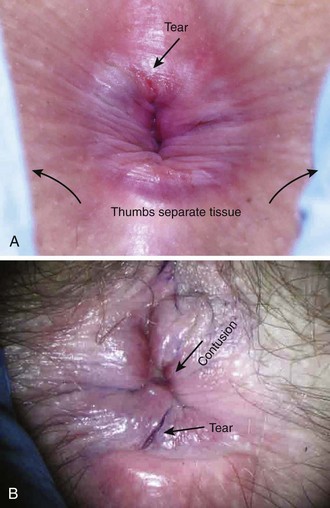

Anal Evaluation

The anal examination follows the genital examination in most cases (Fig. 58-11). Documentation of anal penetration holds significant value because it is a separate crime in addition to vaginal penetration and may increase criminal penalties against convicted sexual predators. Separate the anal folds to look for lacerations and abrasions, and if desired, apply toluidine blue as outlined in the genital section. Collect two external anal swabs before applying the dye. Clean the dye off thoroughly. If anoscopy is not planned, collect the internal rectal sample as follows: separate the anal folds as much as possible and insert swabs approximately 2 cm into the anus. Gently move them in a circular motion and then remove them. Use the swabs to make slides, air-dry them, and include them in the evidence sent to the crime laboratory. Use toluidine blue dye, as described earlier, to better visualize injuries. Anoscopy is indicated to document potential rectal injuries in victims who report anal penetration or describe loss of consciousness during the assault. Perform this procedure in the same manner as diagnostic anoscopy done to evaluate other anal or rectal emergencies in the ED. It is best to collect the internal rectal specimens at the end of the anoscope to prevent contamination from any external sample being dragged internally. In one retrospective observational study of male victims, the use of anoscopy and colposcopy provided superior documentation of injuries over colposcopy alone.26 The location of anoscopically detected injuries may be recorded geographically on an imaginary clock face as with vaginal injuries.

Spermatozoa, Semen, and DNA Testing

Motile and immotile sperm may be found microscopically in wet mounts of vaginal aspirates and in vaginal, oral, and rectal swabs. If formally trained, evaluate the slide microscopically immediately after the physical examination. Examiners find sperm in 13% to 26% of vaginal wet mount specimens.13,27 Early discovery of sperm may be helpful to law enforcement investigations. However, most ED examiners lack formal training in this process and crime laboratories possess much higher sensitivity for detection of sperm, thus making a negative initial wet mount unhelpful. For these reasons, many examiners do not routinely perform the wet mount examination.13 After consensual intercourse with a normal ejaculate, laboratory testing of vaginal secretions detects sperm in 50% of specimens 4 days after coitus.27 However, despite penile penetration during sexual assault, crime laboratories may fail to detect sperm. Reasons for failure include inadequate specimen collection, degradation of the ejaculate, azoospermia, failure of the perpetrator to ejaculate, vasectomy in the perpetrator, washing by the victim, or use of a condom.

A crime laboratory analyst initially looks for semen in a given sample by searching microscopically for sperm on a concentrated specimen and by testing for other components found in semen. Such seminal plasma components include p30 and acid phosphatase. p30 is a glycoprotein specific to the prostate and is regarded as conclusive evidence of semen (i.e., ejaculation within 48 hours), whereas acid phosphatase is presumptive evidence only because it can occur in other body fluids, such as vaginal secretions.28 Although this was a main component of crime laboratory investigation in the past, many laboratories have abandoned the acid phosphatase test in favor of the more specific p30 test.28,29 Despite negative testing for seminal plasma components, laboratories may be able to detect valuable DNA evidence from persistent sperm cells or the perpetrator’s epithelial cells.30,31 As DNA testing technology rapidly changes, the ability of crime laboratories to perform a specific forensic test varies by location and over time. Most crime laboratories look for unique short tandem repeats in perpetrator DNA with PCR amplification testing, which requires minimal material.

Treatment

The approach to prophylaxis for potential diseases transmitted by sexual assault vary by region, disease prevalence, and local practice and is often influenced by the emotional state of the victim and personal and religious viewpoints. We present an overview that may serve as a general guideline, with the understanding that many issues are vague, unsettled, and not totally adopted by all clinicians (Box 58-3).

It is advisable to address the issues of STD, pregnancy, psychological distress, and follow-up in the treatment of a sexual assault victim. Because infection rates before the assault are not known, the risk of contracting an STD as a consequence of a sexual assault has been difficult to determine, and estimates vary widely (Table 58-2).32 Jenny and colleagues found the postassault incidence of STDs to be 2% for Chlamydia and 4% for gonorrhea.33 The reported rates of 12% for Trichomonas and 19% for bacterial vaginosis seem high and may reflect a preexposure infection because male transmission of these infections, especially bacterial vaginosis, is uncommon. We lack specific data on risk for the development of herpes, hepatitis B, or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection from sexual assault. However, HIV transmission has been noted.34

TABLE 58-2

Risk for STDs after Sexual Assault

| DISEASE | RISK (%) |

| Gonorrhea | 6-18 |

| Chlamydia | 4-17 |

| Syphilis | 0.5-3 |

| Human immunodeficiency virus | <1 |

STDs, sexually transmitted diseases.

From Marx J, ed. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2006.

Because victims tend to have relatively low compliance with keeping follow-up visits, most examiners offer, at the least, treatment of gonorrhea and Chlamydia at the time of the initial examination.21 Though most often termed prophylaxis, technically this antibiotic administration is considered “treatment” given so early that the disease is subclinical. The need for routine administration of medication to combat Trichomonas is unclear, and many clinicians do not recommend it as a routine intervention. Prophylaxis for bacterial vaginosis is rarely suggested.

With the increasing prevalence of antibiotic-resistant N. gonorrhoeae, ceftriaxone and cefixime have become the CDC’s recommended antibiotics of choice in targeting gonorrhea after sexual assault. Ceftriaxone also treats incubating syphilis. (The World Health Organization [WHO] also considers a 2-g dose of azithromycin to be effective against incubating syphilis.) No single-dose regimen for gonorrhea is effective against coexisting C. trachomatis infection. Therefore, give patients either a single dose of azithromycin (1 g orally) or a 7-day course of doxycycline (100 mg orally twice a day) or tetracycline (500 mg orally four times a day). A negative pregnancy test is a prerequisite for using either of the latter two antibiotics. Erythromycin may be used as a second alternative for Chlamydia prophylaxis in a pregnant patient. Some examiners administer prophylaxis for Trichomonas with a single 2-g oral dose of metronidazole; although effective and recommended by the CDC,35 this dose of metronidazole may cause significant nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, which can interfere with the efficacy of pregnancy prophylaxis. Box 58-4 provides several options for STD prophylaxis.

Prevention of Hepatitis B

Most sexual assaults involve perpetrators whose hepatitis B status is unknown. In these cases, the CDC recommends hepatitis B vaccination at the time of examination, followed by two more vaccines at the age-appropriate vaccine dose and schedule for previously unvaccinated victims.35 Give the vaccine to victims as soon as possible after the assault. The CDC recommends that it be given within 24 hours, but this may not be possible in all cases. When a perpetrator is known to be hepatitis B antigen positive and the victim is known to be hepatitis B antigen negative and has not been adequately vaccinated, the CDC recommends the administration of hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) in addition to vaccination. HBIG is not recommended if the patient is first seen by medical providers 14 days or more after the sexual exposure. Hepatitis B vaccine should be administered simultaneously with HBIG in a separate injection site, and the vaccine series should be completed at subsequent visits. Complete CDC recommendations for treatment of hepatitis B and other sexually transmitted infections in sexual assault victims can be found at http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2010/sexual-assault.htm.

Prevention of HIV Infection

In a non–assault-related scenario, the risk for transmission of HIV from one episode of unprotected consensual receptive vaginal intercourse with an infected individual is approximately 1 in 1000. The incidence with unprotected receptive anal intercourse is significantly higher at 8 to 32 per 1000.36 However, sexual assault victims often sustain tissue injury because of the violent nature of the act, which may increase the rate of transmission of the virus. Although postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) for parenteral occupational exposure to infected body fluids (i.e., needlestick) is believed to be effective based on case-control studies, there is no proof that PEP for human sexual exposure prevents transmission of the virus.37 Furthermore, victims of sexual assault frequently arrive for treatment much later than those who have occupational exposures.

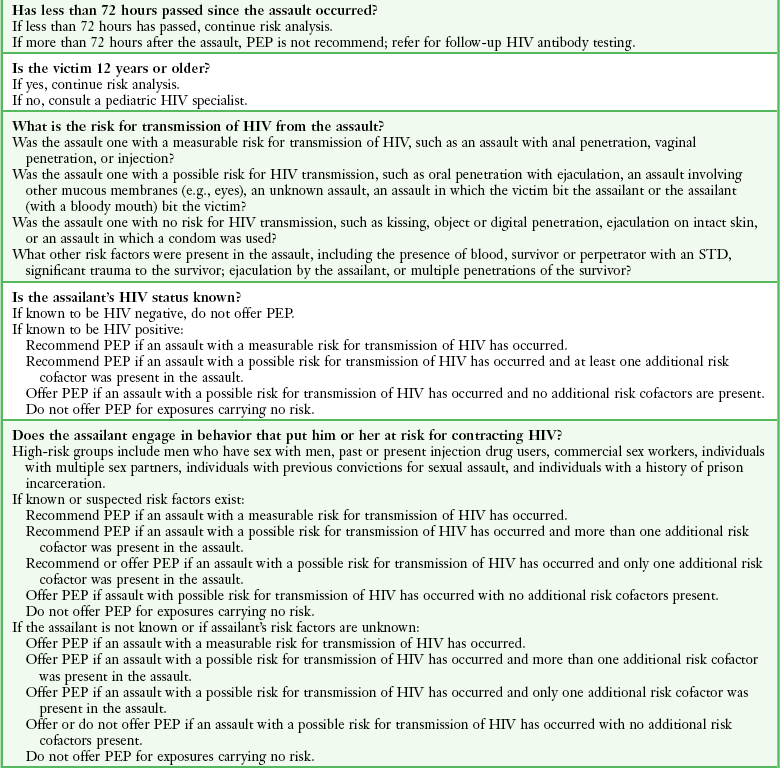

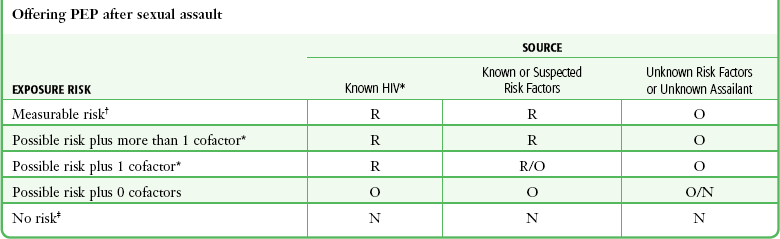

However, 40% of sexual assault victims fear contracting HIV after assault and should, at a minimum, receive counseling and, some argue, the option of taking anti-HIV medications because they may be effective.38,39 Unfortunately, immediate testing of the perpetrator remains a remote option. The majority of cases lack a perpetrator in custody for testing, and few state laws provide for legal preconviction HIV testing of alleged perpetrators.40 In 2005 the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Working Group on Nonoccupational Postexposure Prophylaxis recommended administering PEP to sexual assault victims only in cases in which the perpetrator is known to be HIV positive.41 This recommendation specifies a 28-day medication course for sexual assault victims who arrive for care less than 72 hours after the event with an HIV-positive perpetrator when that exposure represents a substantial risk for transmission (i.e., mucosal contact with genital secretions). As with occupational exposure, antiretroviral medications should be initiated as soon as possible after exposure. For sexual assault exposure with a perpetrator of unknown HIV status, the working group declined to offer a recommendation concerning antiretroviral administration; this must be addressed by practitioners on an individual case-by-case basis.42 Given the extreme negative outcome, the relative safety of treatment, and the lack of conclusive scientific evidence, at least two states have written policies to guide examiners in this complex issue. One such policy is shown in Table 58-3.

TABLE 58-3

Empirical Guide to Offering Postexposure Prophylaxis for HIV

*Acts with a possible risk for transmission of HIV, including oral penetration with ejaculation, unknown act, contact with other mucous membranes, victim biting the assailant, and an assailant with a bloody mouth biting the victim.

†Acts with a measurable risk for transmission of HIV, including anal penetration, vaginal penetration, and injection with a contaminated needle.

‡Acts with no risk for HIV transmission, including kissing; penetration of the vagina, mouth, or anus with digits or objects; and ejaculation on intact skin.

Pregnancy Prophylaxis

Pregnancy occurs in up to 4.7% of sexual assault victims.43 An estimated 22,000 annual rape-related pregnancies could be avoided if all victims received pregnancy prophylaxis within 72 hours.44 Perform a urine pregnancy test before administering postcoital contraception (PCC). Modern urine pregnancy tests possess a detection threshold approaching 20 to 25 mIU/mL and will usually be positive 1 to 2 weeks after conception, often before a menstrual period is missed.

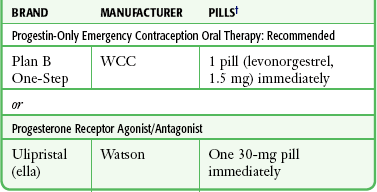

Offer pregnancy prevention with available oral PCC to all sexual assault victims. Several methods can be used to prevent pregnancy after assault (Table 58-4). The drug of choice for PCC is levonorgestrel, which is available in the United States in a commercial kit called “Plan B,” “Plan B One-Step,” or “Next Choice.” The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the sale of Plan B without a prescription for individuals 17 years or older. Although the original Plan B kit included two pills containing 0.75 mg of levonorgestrel, each approved for administration 12 hours apart, a large WHO trial demonstrated that both pills may be taken at once with the same efficacy as the divided dose and the potential for increased compliance.45 The newer Plan B One-Step is a single 1.5-mg pill to be taken as outlined in the WHO study. In the rare instance in which levonorgestrel is unavailable, there are several combined oral contraceptive pills, known as the Yuzpe regimen, that may be used for PCC (see Table 58-4).45 The Yuzpe method is somewhat less effective but prevents approximately 75% of pregnancies that would otherwise have occurred.45 Plan B prevents 89% of pregnancies that would otherwise have occurred and causes fewer side effects. Potential adverse side effects of both methods include nausea, vomiting, and breast tenderness. If the patient vomits within 1 hour of taking a dose, repeat the dose. Some practitioners routinely offer prophylactic antiemetic therapy; others reserve such treatment for patients who vomit. In 2010 the FDA approved a third option for pharmacologic emergency contraception, ulipristal acetate (brand name ella). This selective progesterone receptor modulator has been demonstrated to be as effective as levonorgestrel for prevention of pregnancy 72 hours after intercourse and more effective for longer postcoital use. Ulipristal requires a prescription and is approved for use up to 120 hours after intercourse.46

TABLE 58-4

Note: For the most up-to-date and alternative recommendations and general information, call 1-800-not-2-late or view www.not-2-late.com.

*Some regimens cause nausea and an antiemetic may be used. If vomiting occurs, repeat the dose of antiemetic.

†Alternatively, the older Yuzpe method may be used. Examples include Lo/Ovral or Ogestrel oral contraceptive, two pills immediately and two pills in 12 hours.

All available evidence demonstrates no untoward effects on the fetus should pregnancy occur despite PCC.47 The common practice of obtaining written patient consent for these medications seems unwarranted.

Unfortunately, religious preferences may deter some hospital EDs from providing PCC.48 In these instances, the website and number listed at the end of this paragraph provide practitioners information to give referral for easy access to PCC for patients who cannot obtain Plan B (i.e., those younger than 17 or lacking funds to pay for the medication). In addition, given the ever-increasing availability of new methods and drugs for PCC, examiners may want to obtain up-to-date information from this site (www.not-2-late.com; telephone: 1-800-not-2-late).

Psychological Support

Sexual assault precipitates a psychological crisis for the patient, and psychological care should begin when the patient first arrives in the ED.49,50 Reassure the victim that she will be in control of the examination, that she may ask questions at any point, and that she should notify the examiner if anything hurts or if she needs a break. Giving the victim control over her body and the examination is the first step toward psychological support. Unfortunately, if this is not made a priority, full recovery may be impaired. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), manifested as numbed responsiveness to the external world, disturbances in sleep, feelings of guilt, memory impairment, avoidance of activities, and other symptoms, often develops in sexual assault victims.51 Rape trauma syndrome is the specific label for PTSD in this population.52 Rape trauma syndrome stems from the following characteristics of sexual assault: (1) it is sudden and the victim is unable to develop adequate defenses, (2) it involves intentional cruelty or inhumanity, (3) it makes the victim feel trapped and unable to fight back, and (4) it often involves physical injury. Attention to the initial psychological care of a rape victim in the ED is fundamental and can reduce distress during forensic examination.53

Postexamination Follow-Up

Medical and psychological follow-up of sexual assault victims is essential. Unfortunately, less than one third of victims complete follow-up medical care.54 Many protocols recommend a 2-week follow-up to reexamine any injuries and to repeat testing for STDs and pregnancy. The timing of this follow-up seems to be less important given the widespread use of prophylactic medication to prevent STDs and pregnancy. However, because of the measurable failure rate of PCC, repeated pregnancy testing is critical for a victim who does not experience an expected menses. Further follow-up evaluations may be performed at 4 or 6 weeks and 4 to 6 months to repeat serologic tests for HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and syphilis. In addition, local volunteer support groups can be of immense assistance to a sexual assault victim; contact with such a group should be offered to each victim.

Specific Populations

Male evidentiary examinations include all of the same forensic evidence collection as for female victims except vaginal and cervical specimens. As with all victims, the forensic examination is guided by the history of events related by the victim. Most male victims suffer from anal penetration, or sodomy, by a perpetrator. In addition to rape trauma syndrome, heterosexual male victims may suffer psychological trauma and wonder whether the assault dictates a change in their sexual orientation. Examiners should inform such victims that forced sodomy does not indicate subsequent sexual orientation as a victim may believe that suffering sodomy makes one a homosexual. The increased risk for transmission of HIV with anal intercourse has been noted (see “Prevention of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection” earlier in this chapter). Because of the extreme emotional reaction that men often feel after a sexual assault, they report the crime even more sporadically than female victims do.54,55 Male victims deserve the same unhurried, nonjudgmental manner that female victims do. Penile samples from the shaft, glans, corona, and scrotum may be obtained if there is oral or anal contact with the perpetrator.

Child Sexual Assault Examinations

A well-known study by Adams and associates demonstrated that the majority of children reporting sexual abuse have normal or nonspecific genital findings.56 As these authors succinctly stated regarding child sexual assault, it is “normal to be normal.” Despite expert physical examination, the vast majority of sexually abused children cannot be differentiated from nonabused children.57 Discovery of one of the rare examination markers of injury should be confirmed by experts, and a discussion of these findings, though beyond the scope of this chapter, is covered extensively in other resources.58 The potential sexual assault history provided by the child or caretaker should therefore remain the primary indicator that inappropriate genital contact has occurred. At the very least, the history warrants an investigation of the possibility of sexual abuse.

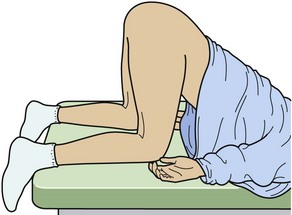

It cannot be emphasized enough that the examiner’s responsibility in the care of a child victim of sexual abuse remains within the realm of experts. However, in EDs lacking timely availability of local experts, inspect the genitalia carefully in an unhurried, child-friendly manner, and if indicated, collect forensic specimens. For a very young child with small genital orifices, the aid of a magnification source may be extremely helpful. Ask a parent to assist in the calming, reassurance, and positioning of the child for careful inspection. However, when the parent is a suspect, the practitioner must exclude that parent from the examination. Whereas the basic lithotomy position may be used for an older, more mature child or an adolescent patient, use of alternative positioning of a pediatric female patient is essential for inspection. The frog leg position (the feet together and the knees spread widely apart) with the use of labial or gluteal (or both) separation and traction is often beneficial in children (Fig. 58-12). Take care to gently separate the labia to avoid superficial examiner-induced injuries. In addition, to get a better look at the hymenal perimeter in prepubertal girls and the anus in girls and boys, ask them to turn over into the knee-chest position (Fig. 58-13). Genital findings that are deemed definitive of sexual abuse or penetration or are nonspecific are included in Box 58-5. However, many normal hymenal differences exist from one child to the next, and the definitive diagnosis of “abnormal” is often difficult even for experts. When any doubt exists in the ED, describe the findings and refer the child for later examination by experts. The availability of a colposcope or alternative photographic equipment with magnification clearly aids in the documentation of any injuries that may heal before examination by an expert can be performed.

Figure 58-12 “Frog leg” position to examine children.

Genital specimens to screen for STDs remain a controversial issue in the realm of child abuse experts. For N. gonorrhoeae, at least, the literature supports the notion that all infected children will display an abnormal discharge.59 With very young children, the practitioner may have only one opportunity to collect vaginal specimens without causing agitation prohibiting further examination. Forcing specimen collection under physical restraint is considered a second assault on the child. Because the child is being evaluated for possible sexual abuse, the primary specimens collected should be for forensic DNA analysis. STD detection and treatment can be performed at a later time. Clinicians should consult local child abuse centers for protocols regarding immediate STD specimen collection, referral, and follow-up services.

Suspect Examinations

The physical and evidentiary examination of the suspect is similar to that of the victim. The primary differences lie in history taking, reference samples, and more “blind” samples. During the examination of a suspect, law enforcement officers rather than the suspect provide the history of the event. Collect reference samples of head and pubic hairs, as well as blood, saliva, and urine, if possible. Apply special attention not only to nail scrapings but also to swabbing all the fingers for possible vaginal epithelial cells from digital penetration. The shaft and corona of the glans penis should be swabbed along with separate swabs of the scrotum for vaginal secretions. With an unwashed penis, swabs almost uniformly show evidence of female cells up to 24 hours after coitus.30

The Unconscious Victim and “Drug-Facilitated Sexual Assault”

Alcohol and other drugs play an important role in many sexual assaults. Half of all sexual assaults involve drug or alcohol ingestion.60 In many cases it is unclear whether a drug was taken voluntarily or whether it was surreptitiously given to the assaulted victim.

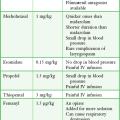

Popular media has raised public awareness of drugs used to facilitate sexual assault under the term date-rape drugs (Box 58-6).61 Although date-rape drugs are of significant concern, extensive forensic testing in the United States shows that a minority of sexual assault cases involve the scenario in which a victim’s drink is covertly spiked with a tablet, capsule, powder, or liquid containing mind-altering drugs.62 However, laboratory testing may be inadequately sensitive to test for all substances used during drug-facilitated sexual assault. The drugs most commonly associated with drug-facilitated sexual assault are ethanol, marijuana, cocaine, and benzodiazepines. Frequently, more than one drug is found. Although any type of sedative or hypnotic drug, or a combination of both, may be used to facilitate sexual assault, the most publicized drugs include flunitrazepam (Rohypnol), γ-hydroxybutyrate (GHB), and most recently, beverages containing high amounts of alcohol and caffeine (for example, Four Loko).62,63 In previous decades, laboratory testing implicated flunitrazepam and GHB in drug-facilitated sexual assault in approximately 3% to 5% of cases.61 Flunitrazepam is a benzodiazepine unavailable in the United States but available in Mexico. It can be detected in urine up to 3 weeks after ingestion.64 In the United States, GHB is a schedule 1, federally banned central nervous system depressant. Legally, it is available only by prescription as the drug Xyrem for narcolepsy with a schedule 3 exception, but it can easily be manufactured illegally by users. It can be detected in drinking material residue by crime laboratories as well in the victim’s urine up to 4 hours after a sufficiently large ingestion. Drugs similar to GHB are 1,4 butanediol and γ-butyrolactone.

Sexual Assault Response Teams

1. The practitioner performing the examination is specifically dedicated to treating the victim, not tending to multiple patients in a busy ED.

2. The clinician has usually completed more extensive training on sexual assault examination (mean of 80 hours) and evidence collection and, accordingly, may perform a more comprehensive examination with better collection of evidence.21,65

3. Many involved feel that designated clinicians consider the emotional needs of the victim more fully because of their extra specialty training.

Useful guidelines and resources for establishing SANE programs are currently available.2,3,63,66

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System [online], Atlanta, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009. Available at, http://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/nfirates2001.html. [Cited April 23, 2011].

2. The Violence Against Women and Department of Justice Reauthorization Act, 42 U.S.C. §3796gg-4d.

3. American College of Emergency Physicians. Evaluation and Management of the Sexually Assaulted or Sexually Abused Patient. Atlanta, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1999.

4. Morrison, AI. Persistence of spermatozoa in the vagina and cervix. Br J Vener Dis. 1972;48:141.

5. Rambow, B, Adkinson, C, Frost, TH, et al. Female sexual assault: medical and legal implications. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:727.

6. Wawryk, J, Odell, M. Fluorescent identification of biological and other stains on skin by the use of alternative light sources. J Clin Forensic Med. 2005;12:296–301.

7. Santucci, KA, Nelson, DG, McQuillen, KK, et al. Wood’s lamp utility in the identification of semen. Pediatrics. 1999;104:1342.

8. Gabby, T, Winkleby, MA, Boyce, WT, et al. Sexual abuse of children: the detection of semen on skin. Am J Dis Child. 1992;146:700.

9. Enos, WF, Beyer, JC. Spermatozoa in the anal canal and rectum and in the oral cavity in female rape victims. J Forensic Sci. 1978;23:231.

10. Mann, MJ. Hair transfers in sexual assault: a six-year case study. J Forensic Sci. 1990;35:951.

11. Slaughter, L, Brown, CRV, Crowley, S, et al. Patterns of genital injury in female sexual assault victims. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:609.

12. Sugar, NF, Fine, DN, Eckert, LO. Physical injury after sexual assault: findings of a large case series. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:71–76.

13. Riggs, N, Houry, D, Long, G, et al. Analysis of 1,076 cases of sexual assault. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35:358.

14. Biggs, M, Stermac, LE, Divinsky, M. Genital injuries following sexual assault of women with and without prior sexual intercourse experience. CMAJ. 1998;159:33.

15. Teixeira, WRG. Hymeneal colposcopic examination in sexual offenses. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1981;2:209.

16. Jones, JS, Rossman, L, Hartman, M, et al. Anogenital injuries in adolescents after consensual sexual intercourse. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:1378–1383.

17. Kellogg, ND, Menard, SW, Santos, A. Genital anatomy in pregnant adolescents: “normal” does not mean “nothing happened.”. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e67–e69.

18. Tagatz, GE, Okagaki, T, Sciarra, JJ. The effect of vaginal lubricants on sperm motility in vitro. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1972;113:88.

19. Cartwright, PS. Factors that correlate with injury sustained by survivors of sexual assault. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;70:44.

20. Rupp, JC. Sperm survival and prostatic acid phosphatase activity in victims of sexual assault. J Forensic Sci. 1968;14:177.

21. Ciancone, AC, Wilson, C, Collette, R, et al. Sexual assault nurse examiner programs in the United States. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35:353.

22. Lauber, AA, Souma, ML. Use of toluidine blue for documentation of traumatic intercourse. Obstet Gynecol. 1982;60:644.

23. McCauley, J, Gorman, RL, Guzinski, G. Toluidine blue in the detection of perineal lacerations in pediatric and adolescent sexual abuse victims. Pediatrics. 1986;78:1039.

24. Hochmeister, MN, Whelan, M, Borer, UV, et al. Effects of toluidine blue and destaining reagents used in sexual assault examinations on the ability to obtain DNA profiles from postcoital vaginal swabs. J Forensic Sci. 1997;42:316.

25. Redman, RS, Krasnow, SH, Sniffen, RA. Evaluation of the carcinogenic potential for toluidine blue O in the hamster cheek pouch. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;74:473.

26. Ernst, AA, Green, E, Ferguson, MT, et al. The utility of anoscopy and colposcopy in the evaluation of male sexual assault victims. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;36:432.

27. Davies, A, Wilson, E. The persistence of seminal constituents in the human vagina. Forensic Sci. 1974;3:45.

28. Kamenev, L, Leclercq, M, Francois Gerard, C. Detection of p30 antigen in sexual assault case material. J Forensic Sci Soc. 1990;30:193.

29. Graves, H, Sensabaugh, G, Blake, E. Postcoital detection of a male-specific semen protein. Application to the investigation of rape. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:338.

30. Collins, KA, Cina, MS, Pettanati, MJ, et al. Identification of female cells in postcoital penile swabs using fluorescence in situ hybridization. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:1080.

31. Rao, PN, Collins, KA, Geisinger, KR, et al. Identification of male epithelial cells in routine postcoital cervicovaginal smears using fluorescence in situ hybridization. Am J Clin Pathol. 1995;104:32.

32. Schiff, AF. A statistical evaluation of rape. Forensic Sci. 1973;2:339.

33. Jenny, C, Hooton, TM, Bowers, A, et al. Sexually transmitted diseases in victims of rape. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:713.

34. Vandercam, B, Therasse, P, Aziz, M, et al. HIV infection and rape. Acta Urol Belg. 1992;60:77.

35. Centers for Disease Control and PreventionWorkowski, KA, Berman, SM, Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep, 2006;55(No. RR-11):1–94. Available at, http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2006/sexual-assault.htm35a. [MMWR Recommendations and Reports. Appendix B. December 8, 2006;55(RR-16):30-31].

36. Royce, RA, Sena, A, Cates, W, et al. Sexual transmission of HIV. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1072.

37. Cardo, DM, Culver, DH, Ciesielski, CA, et al. A case-control study of HIV seroconversion in health care workers after percutaneous exposure. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1485.

38. Gostin, LO, Lazzarini, Z, Alexander, D, et al. HIV testing, counseling, and prophylaxis after sexual assault. JAMA. 1994;271:1436.

39. Lurie, P, Miller, S, Hecht, F, et al. Postexposure prophylaxis after nonoccupational HIV exposure: clinical, ethical, and policy consideration. JAMA. 1998;280:1769.

40. Myles, JE, Hirozawa, A, Katz, MH, et al. Postexposure prophylaxis for HIV after sexual assault. JAMA. 2000;284:1516.

41. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwR/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5402a1.htm.

42. Wiebe, ER, Comay, SE, McGregor, M, et al. Offering HIV prophylaxis to people who have been sexually assaulted: 16 months’ experience in sexual assault service. CMAJ. 2000;162:641.

43. Holmes, MM, Resnick, HS, Kilpatrick, DG, et al. Rape-related pregnancy: estimates and descriptive characteristics from a national sample of women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:320.

44. Stewart, FH, Trussell, J. Prevention of pregnancy resulting from rape. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19:228.

45. von Hertzen, H, Piaggio, G, Ding, J, et al. Low dose mifepristone and two regimens of levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a WHO multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1803–1810.

46. Glasier, AF, Cameron, ST, Fine, PM, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomized non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;25:345–363.

47. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Prescription drug products: certain combined oral contraceptives for use as postcoital emergency contraception. Fed Regist. 1997;62:8610.

48. Trussell, J, Rodriguez, G, Ellerston, G. Updated estimates of the effectiveness of the Yuzpe regimen of emergency contraception. Contraception. 1999;59:147.

49. Task Force on Postovulatory Methods of Fertility Regulation. Randomized controlled trial of levonorgestrel versus the Yuzpe regimen of combined oral contraceptives for emergency contraception. Lancet. 1998;352:428.

50. Korba, VD, Heil, CG, Jr. Eight years of fertility control with norgestrel–ethinyl estradiol (Ovral): an updated clinical review. Fertil Steril. 1975;26:973.

51. Smugar, SS, Spina, BJ, Merz, JF. Informed consent for emergency contraception: variability in hospital care of rape victims. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1372.

52. Burgess, AW, Holstrom, LL. Rape trauma syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1974;131:981.

53. Resnick, H. Prevention of post-rape psychopathology: preliminary findings of a controlled acute rape treatment study. Anxiety Disord. 1999;13:359.

54. Holmes, MM, Resnick, HS, Frampton, D. Follow-up of sexual assault victims. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:336.

55. Holmes, WC, Slap, GB. Sexual abuse of boys: definition, prevalence, correlates, sequelae, and management. JAMA. 1998;280:1855.

56. Adams, JA, Harper, K, Knudson, S, et al. Examination findings in legally confirmed child sexual abuse cases: it’s normal to be normal. Pediatrics. 1994;94:310.

57. Berenson, AB, Chacho, MR, Weimann, CMK, et al. A case-control study of anatomic changes resulting from sexual abuse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:820.

58. Heger, A, Emans, SJ. Evaluation of the Sexually Abused Child: A Medical Textbook and Photographic Atlas. New York: Oxford University Press; 1992.

59. Sicoli, RA, Losek, JD, Hudlett, JM, et al. Indications for Neisseria gonorrhoeae cultures in children with suspected sexual abuse. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149:86.

60. Abbey, A, Zawacki, T, Buck, PO, et al. Alcohol and sexual assault. Alcohol Res Health. 2001;25:43.

61. Schwartz, RH, Milteer, R, LeBeau, M. Drug-facilitated sexual assault (“date rape”). South Med J. 2000;93:558.

62. Slaughter, L. Involvement of drugs in sexual assault. J Reprod Med. 2000;45:425.

63. http://www.campussafetymagazine.com/Channel/University-Security/News/2010/10/26/Alcoholic-Energy-Drinks-Not-Date-Rape-Drugs-Linked-to-Central-Washington-U-Hospitalizations.aspx.

64. Negrusz, A, Moore, CM, Stockham, TL, et al. Elimination of 7-aminoflunitrazepam and flunitrazepam in urine after a single dose of Rohypnol. J Forensic Sci. 2000;45:1031.

65. Ledray, LE, Simmelink, K. Efficacy of SANE evidence collection: a Minnesota study. J Emerg Nurs. 1997;23:75.

66. Smith, K, Holmseth, J, MacGregor, M, et al. Sexual assault response team: overcoming obstacles to program development. J Emerg Nurs. 1998;24:365.