Chapter 611 Examination of the Eye

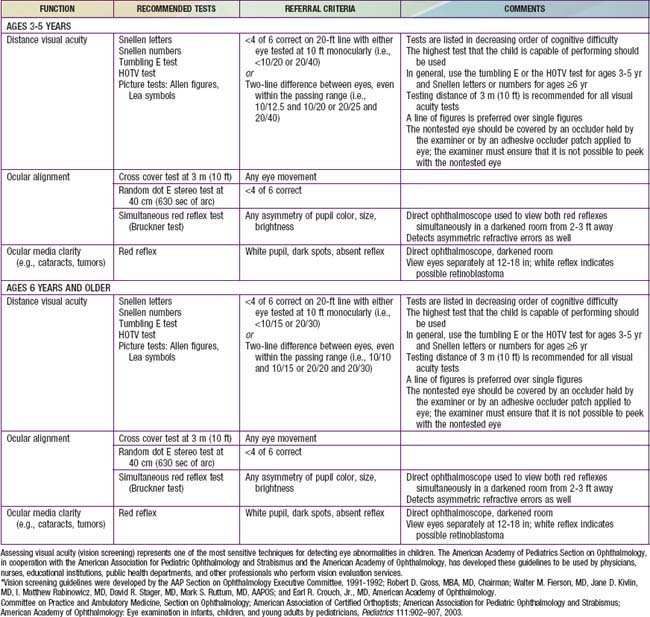

Examination of the eyes is a routine part of the periodic pediatric assessment beginning in the newborn period. The primary care physician is very important in detecting both obvious and insidious asymptomatic eye diseases. Screening by lay persons in schools and community programs can also be effective in detecting problems early. The best method of screening (ages 3-5 yrs) is currently being investigated. The American Academy of Ophthalmology recommend preschool vision screening as a means of reducing preventable visual loss (Table 611-1). This testing should also be done by pediatricians during well child visits. Children should be examined by an ophthalmologist whenever a significant ocular abnormality or vision defect is noted or suspected. Children who are at high risk of ophthalmologic problems, such as genetically inherited ocular conditions and various systemic disorders, should also be examined by an ophthalmologist.

Pupillary Examination

Examination of the pupils includes evaluation of both, the direct and consensual reactions to light, the reaction on near gaze, and the response to reduced illumination, noting the size and symmetry of the pupils under all conditions. Special care must be taken to differentiate the reaction to light from the reaction to near gaze. A child’s natural tendency is to look directly at the approaching light, inducing the near gaze reflex when one is attempting to test only the reaction to light; accordingly, every effort must be made to control fixation. The swinging flashlight test is especially useful for detecting unilateral or asymmetric prechiasmatic afferent defects in children (see “Marcus Gunn Pupil” section in Chapter 614).

Ocular Motility

Ocular motility is tested by having a child follow an object into the various positions of gaze. Movements of each eye individually (ductions) and of the two eyes together (versions, conjugate movements, and convergence) are assessed. Alignment is judged by the symmetry of the corneal light reflexes and by the response to alternate occlusion of each eye (see discussion on cover tests for strabismus in Chapter 615).

Bennett DM, Gordon G, Dutton GN. The useful field of view test, normative data in children of school age. Optom Vis Sci. 2009;86:717-721.

Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine, Section on Ophthalmology; American Association of Certified Orthoptists; American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus; American Academy of Ophthalmology. Eye examination in infants, children, and young adults by pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2003;111:902-907.

Donahue SP, Johnson TM, Ottar W, et al. Sensitivity of photoscreening to detect high-magnitude amblyogenic factors. J AAPOS. 2002;6:86-91.

Fulton A. Screening preschool children to detect visual and ocular disorders. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992;110:1553-1554.

Isenberg SJ. Clinical application of the pupil examination in neonates. J Pediatr. 1991;118:650-652.

Powell C, Hatt SR: Vision screening for amblyopia in childhood. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3):CD005020, 2009.

Reinecke RD. Screening 3-year olds for visual problems: are we gaining or falling behind? Arch Ophthalmol. 1986;104:245-248.

Salcido AA, Bradley J, Donahue SP. Predictive value of photoscreening and traditional screening of preschool children. J AAPOS. 2005;9:114-120.

Simons K. Preschool vision screening: rationale, methodology and outcome. Surv Ophthalmol. 1996;41:3-30.

Solouki AM, Verhoeven VJM, van Duijn CM, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies a susceptibility locus for refractive errors and myopia at 15q14. Nat Genet. 2010;42(10):897-901.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Vision screening for children 1 to 5 years of age: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. Pediatrics. 2011;127:340-346.