12 Evaluation and pelvic floor management of urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes

Introduction

Urologic disorders and pelvic pain present an obvious relationship. A large proportion of the human population has endured pain or discomfort of a simple urinary tract infection. And one of the earliest adventures in human surgical intervention arose in the centuries BC as the Greeks ‘cut for stone’ to relieve the obstruction and pain of urinary bladder calculi. However, now that most of the urogynaecologic organ maladies of infection, neoplasia and obstruction are understood, we are still left with a noisome bag of discomforts lacking any clear pathogenesis. These are the urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes (UCPPS). The majority of these conditions arise from either a possible urinary bladder source known as bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis (BPS/IC) or prostate source known as prostate pain syndrome (PPS), named chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) in the United States. The European Association of Urology attempted to update and provide a classification of pelvic pain disorders to suggest avenues for further management (Fall et al. 2010). Their pelvic pain descriptions fit into neat little boxes of urological, gynaecological, anorectal, neuromuscular and ‘other’ categories. These non-malignant pain conditions or syndromes perceived in structures related to the pelvis of both males and females do not deserve more specific diagnoses because the aetiology and pathogenesis remains a mystery – ‘a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma’ – and we depend on a complex symptomatic analysis to help guide us in evaluation and therapy. Regrettably the final common pathway often defaults as a referral to a pain management team. While awaiting elucidation of the cellular and molecular pathogenic mechanisms of UCPPS, we should rely on a diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm to direct logical evaluation and multimodal management. We must develop alternative ways of thinking about managing these urologic pain conditions. UCPPS needs to be viewed as much more than an organ-specific disease, but rather as a biopsychosocial disorder. The central problem is pain. Traditional biomedical treatment for UCPPS has failed (Anderson 2006). Antibiotics, α-blocking agents and anti-inflammatory agents as well as virtually all other pharmaceuticals have shown unimpressive outcomes in ameliorating the effects of these disorders. The biopsychosocial model of this condition rather than the biomedical model holds the key to understanding the pathogenesis and possible future treatments. Phenotyping is one current trend and we recommend it for approaching patients with these disorders allowing specific guideline development for multimodal therapy (Baranowski et al. 2008, Nickel et al. 2009, Shoskes et al. 2009). Some of the recent developments and approaches arose from clinical investigation and treatment protocols supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the United States over the past 10 years. A descriptive phenotyping classification allows understanding of epidemiology, aetiology and potential design of randomized clinical trials. Clinically identifiable domains suggested include: urinary, psychosocial, organ specific, infection, neurological/systemic and muscle tenderness (Nickel & Shoskes 2009, Shoskes et al. 2009) (Table 12.1).

Table 12.1 Percentage of patients with specific myofascial trigger point tenderness

| Muscle groups | % Patients with trigger point tenderness, N = 72 |

|---|---|

| Internal muscles | |

| Puborectalis/pubococcygeus | 90.3 |

| Coccygeus | 34.7 |

| Sphincter ani | 16.6 |

| External muscles | |

| Rectus abdominis | 55.6 |

| External oblique | 52.8 |

| Adductors | 19.4 |

| Gluteus medius | 18.1 |

| Gluteus maximus | 6.9 |

| Bulbospongiosus | 12.5 |

| Transverse perineal | 11.1 |

Urologic diagnostic evaluation

Prostate pain syndrome

Chronic prostatitis is an incorrect label; we are dealing with a variable set of pain conditions with no objective markers and multivariate symptoms. The disorder is not prostatocentric symptomatology and pain sites exist between the umbilicus to above the mid thigh. The European Community has promoted the term prostate pain syndrome (PPS) as a more generic term over the NIH category III chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS). Still, it smacks of a prostatocentric approach, which is probably to be avoided for lack of evidence, and it encourages the use of antibiotics as standard therapy that clearly lacks efficacy. By definition, PPS is persistent discomfort or pain in the pelvic region with sterile specimen cultures and either significant or insignificant white blood cell counts in prostate specimens: semen, expressed prostatic secretion or urine collected after prostate massage. There does not appear to be any diagnostic or therapeutic advantage to differentiating between those patients with significant or insignificant leucocytes from the prostate (Schaeffer et al. 2002); however, in the author’s experience, men with no prostate inflammation appear to suffer greater degrees and longer duration of pelvic pain on average.

Medical history

We utilize symptom questionnaires and validated instruments to detail patient psychological issues. These tools help quantify the baseline, eventual progress and outcome of our management techniques. The most widely used research tool is the National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI). An alternative type of CPPS symptom questionnaire – the Pelvic Pain Symptom Score (PPSS) – has also been useful in our hands. The PPSS expands the description of named painful anatomical locations and grades the severity of pain (0 to 4+); it includes urinary symptoms that mimic the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), and scores sexual dysfunction aspects of the patient condition as a separate domain. Our group utilized this questionnaire in the treatment outcome analyses of pelvic floor therapy (Anderson et al. 2005, 2006). We have also used other psychosocial instruments including Brief Symptom Inventory, Beck Anxiety, and Perceived Stress Scale to study neuroendocrine psychiatric influences associated with CPPS (Anderson et al. 2008).

Physical examination

Prostatic massage has been utilized as treatment for CP by several generations of urologists, particularly prior to the advent of antibiotics. In a report from a popular Philippine study, repeated prostatic massages reveal occult micro-organisms. Therapeutic benefit from massage derives from expression of poorly emptying ductal acini and may diminish smooth muscle prostatic pressure. Some have proposed massage plus antibiotic treatment (Shoskes & Zeitlin 1999). In his study, prostate massage plus antibiotics for 2–8 weeks produced 40% resolution of symptoms, 20% significant improvements; however, 40% had no improvement. There was no correlation between inflammatory content and bacterial cultures. Our opinion favours repetitive massage of the prostate, not for emptying the gland, but rather to relieve pelvic tension and release myofascial TrPs. We continue to be extremely sceptical of the concept of occult bacteria that need to be ‘massaged out’.

Imaging of the prostate in chronic prostatitis

We recommend transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) to image the prostate gland. It has not gained wide acceptance as a method of evaluation for PPS but may provide valuable information demonstrating inflamed tissue, the presence of stones in the ducts (representing urinary mineral deposits), swelling and thickening of seminal vesicles (semen storage organs behind the prostate) and accurate measurement of the size of the gland. Abdominal ultrasound and CT are inaccurate and magnetic resonance of the prostate is not cost-effective. Many urologists have observed intraprostatic calcifications on TRUS. Older men (55+) develop benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and it commonly associates with PPS. Most workers believe the ultrasound hyperdense areas represent deposits of urinary metabolite crystals and inspissated secretions within the ducts. These concretions are commonly seen exuding from the peripheral zone of the prostate at the time of transurethral resection. It has been noted, however, that a substantial percentage of younger men with chronic prostate or pelvic pain have such calcifications (Geramoutsos et al. 2004). Shoskes et al. (2007) imaged 47 men with PPS symptoms averaging 60 months and reported 47% of them had such calcifications. There was no difference in the CPSI score between those who did or did not have the finding; however, the men with stones had less discomfort and greater leucocyte presence.

Urodynamics

Many workers suggest relationships between chronic pain and smooth or striated muscle function of the urinary bladder, prostate or sexual organs. Small, undocumented reports of findings in PPS patients suggest possible avenues of scientific pursuit. Comparison of symptoms, morphological, microbiological and urodynamic findings in patients with PPS have existed for decades (Strohmaier & Bichler 2000, Lee 2001, Hetrick et al. 2006, Hafez 2009). A common theme emerges suggesting functional obstruction at the level of the bladder neck and external sphincter, high sensitivity during filling cystometry, and poor or interrupted urinary flow. Abnormally low urinary flow rates <15 ml/s were found in 65% of patients. Some patients respond to α-blocking agents as therapy for UCPPS while most do not.

Isolated male orchalgia (pain in the testicles)

Chronic orchalgia, or pain in the testis, vexes a lot of young men and they reluctantly bring this to the attention of their physician. Some would suggest that isolated male orchalgia does not belong with the phenotypes of PPS. However, pelvic floor dysfunction studies suggest an extremely large proportion of these patients (88%) exhibit an increased pelvic floor resting tone at a mean of 6.7 μV – values >3.0 μV are considered abnormal (Planken et al. 2010). Testicular pain occurs most commonly in young men in their 20s and 30s and requires a careful history and physical examination because this is also the age group where testicular cancer most commonly occurs. Usually the examination is negative, with the patient complaining of pain localized to one side or the other but occasionally bilateral, and when the epididymis is squeezed during examination it reproduces the pain for the patient. Rarely does a vasectomy result in such tenderness or chronic orchalgia. The common urologic diagnosis is sterile epididymitis, but there is virtually no evidence for any inflammatory condition.

Removal of the epididymis as an approach to treat chronic testis pain has met with variable success and positive results range from 32% (Sweeney et al. 2008) to 85% in post-vasectomy pain (Hori et al. 2009). Selective denervation is also successful using a microscopic method to remove all nerve fibres from the spermatic cord arising from the testicular tissue or the scrotal contents. We always perform at least three selective long-acting anaesthetic spermatic cord nerve blocks as a diagnostic trial, usually with a cortisone solution. Several of these nerve blocks at intervals may relieve the cyclical nature of this syndrome. Microscopic denervation after successful spermatic cord block has shown successful results with complete relief of pain in 76–97% of selected patients (Levine & Matkov 2001, Heidenreich et al. 2002). A recent report suggests that sacral nerve root electrical stimulation may be beneficial in these patients, and in some cases skin surface electrical stimulation has been helpful (McJunkin et al. 2009).

Pudendal nerve entrapment (pudendal neuralgia)

We should mention the concept of the pudendal nerves being compressed, stretched or entrapped in the pelvis as a potential cause of chronic pelvic pain. There are five essential diagnostic criteria (Stav et al. 2009):1. Pain along the anatomical distribution of the pudendal nerve; 2. The pain aggravated by sitting; 3. The patient is not awakened at night by the pain; 4. There is no objective sensory loss on clinical examination; 5. The pain is improved by an anaesthetic pudendal nerve block.

Neuromuscular treatment

It is beyond the scope of this chapter to discuss the myriad therapeutic modalities that have been utilized to relieve UCPPS. We refer the reader to previous chapters and review articles with the caveat that very few level 1 or 2 evidence-based treatments have been documented and most cannot be recommended (Hanno et al. 2010). Traditional therapy includes antibiotics, α-blockers, anti-inflammatory agents, phytotherapy, minimally invasive therapies, heat therapy, neuromodulation and surgical invasion, including the extreme of radical extirpation of the urinary bladder and/or prostate. While urologists are trained surgeons, surgical procedures have failed to offer any solution to the CPPS. Urologists should carefully consider alternative and complementary methods of patient care, especially in relationship to CPP. At the same time, medical practice guidelines should be evidence-based and not advocated solely on opinions of efficacy. Well-educated patients and patient advocates seek greater control of their treatment and the planning thereof by focusing on preventative maintenance issues and partnering with physicians in managing their disorder.

Neuromuscular basis for therapy

Many investigators believe that the source of pain and dysfunction in men and women with CPP, including chronic testicular pain, relates to chronically tense myofascial tissue in and around the pelvic floor (Anderson et al. 2005, Berger et al. 2007, Planken et al. 2010). In simple and broad terms we can describe the neuromuscular disorder as pelvic myoneuropathy. Traditionally, the diagnosis of UCPPS depends upon a descriptive symptom complex. However, it is now clear that UCPPS is multifaceted and not all patients have the same constellation of symptoms, or respond in the same way to single treatment modalities. Because the pathogenic mechanisms associated with the development of pelvic genitourinary symptoms are unknown, it remains difficult to explain the role of painful myofascial tissue. One of the phenotypes proposed for UCPPS includes a domain of tenderness of skeletal muscle and this has been the focus of a growing number of clinical research trials and publications. A recent NIH-sponsored, multicentre study demonstrated the feasibility of performing clinical therapeutic trials utilizing muscle and connective tissue physiotherapy (myofascial physical therapy) to treat UCPPS (Fitzgerald et al. 2009). A comparator group of subjects was randomized to receive total-body traditional Western massage with no myofascial release or internal pelvic therapy. In the NIH trial the original physician investigators quantified the degree of tenderness in muscle groups prior to corroboration by physical therapists trained in such techniques. A clear discrepancy existed between what physicians scored for subjective pain on examination and what the physical therapists reported; physicians found 28% less tenderness on their examination (P < 0.01). Patients randomized to the myofascial physical therapy group underwent connective tissue manipulation to all body wall tissues of the abdominal wall, back, buttocks and thighs as well as internal pelvic muscles clinically found to contain connective tissue abnormalities and/or myofascial TrP release to painful myofascial TrPs. This was done until a texture change was noted in the treated tissue layer. Manual techniques such as TrP barrier release with or without active contraction or reciprocal inhibition, manual stretching of the TrP region and myofascial release were used on the identified TrPs. A secondary outcome of the pilot study revealed good patient response to the internal and external myofascial physical therapy as compared to generalized external Western massage only (57% versus 28%, respectively). This form of therapy was expanded to a larger trial in women suffering from IC/PBS and the results show an equally impressive response to the manual physical therapy.

Progress of discovery and understanding of chronic pain syndromes and myofascial trigger points

• 1838 Recaimer – First describes syndrome of tension myalgia of pelvic floor in ‘Stretching massage and rhythmic percussion in the treatment of muscular contractions’.

• 1937 Thiele – Describes tonic spasms of levator ani, coccygeus and piriformis muscles and their relationship to pain.

• 1942 Travell et al. – First description of myofascial TrPs as common cause of chronic muscle pain.

• 1951 Dittrich – First recognized pelvic pain occurring as a result of referral from TrPs in subfascial fat and perifascial tissue.

• 1963 Thiele – Successful use of digital massage of spastic levator muscles subsequently described as ‘Thiele massage’.

• 1977 Sinaki et al. – Consolidates various syndromes of pelvic musculature under one terminology: tension myalgia of the pelvic floor. Uses combined treatment with rectal diathermy, Thiele’s massage and relaxation exercises.

• 1983 Travell and Simons – Publish the first edition of Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual in 1983; identifying internal muscles and areas of referred pain from myofascial TrPs. Second edition published in 1992.

• 1984 Slocum – Treats TrPs related to the abdominal pelvic pain syndrome in women using locally injected anaesthetic. Indicates emotional stress frequently a potentiating factor, not a cause for CPP.

• 1994 Hong – Developed rabbit animal model to identify myofascial TrPs. With colleagues, subsequently publishes 36 animal clinical and 12 basic science articles to advance our understanding.

• 2004 Simons – Reviews the present understanding of myofascial TrPs as they relate to musculoskeletal dysfunction.

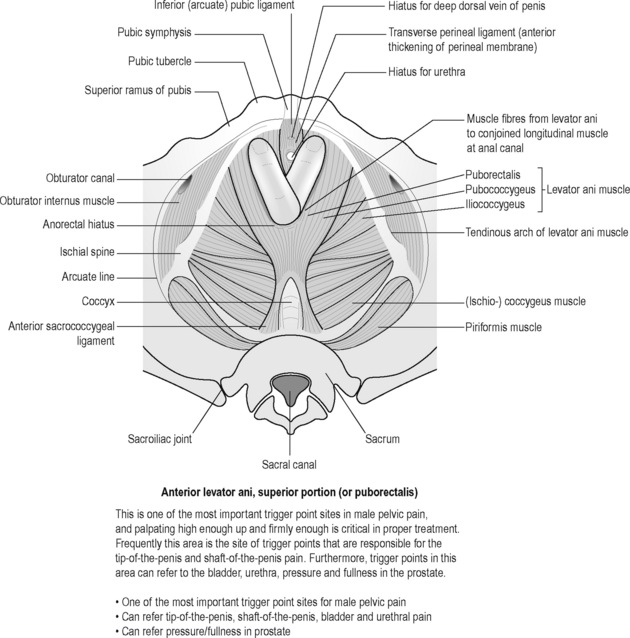

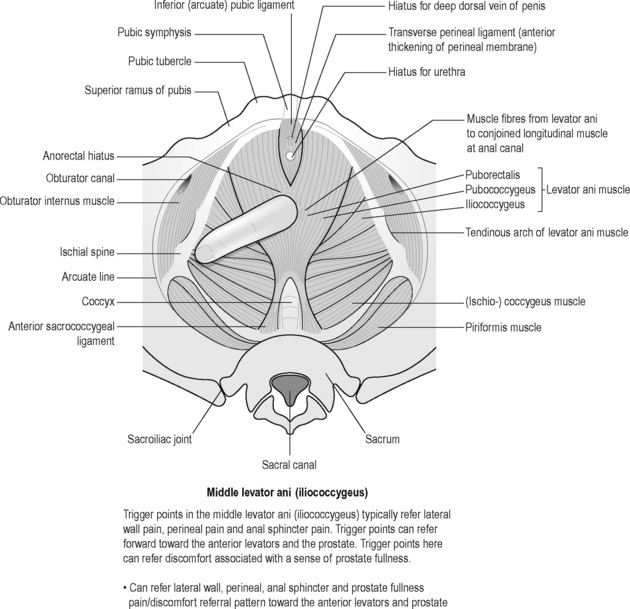

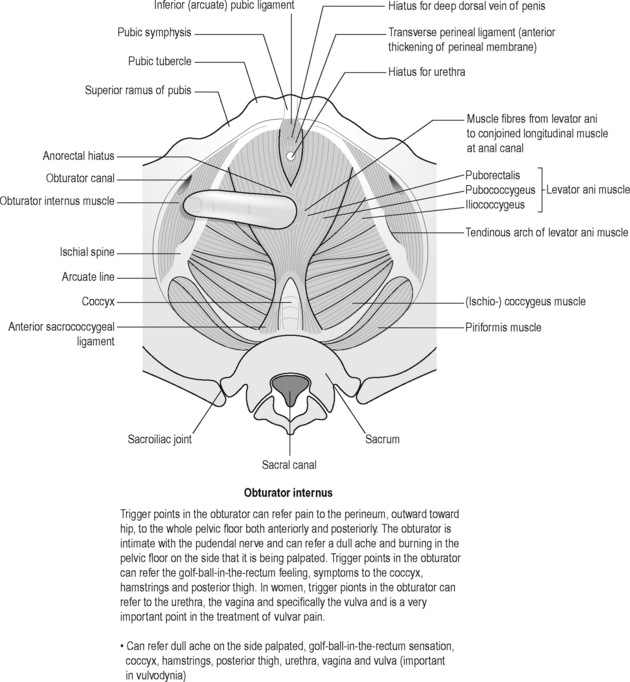

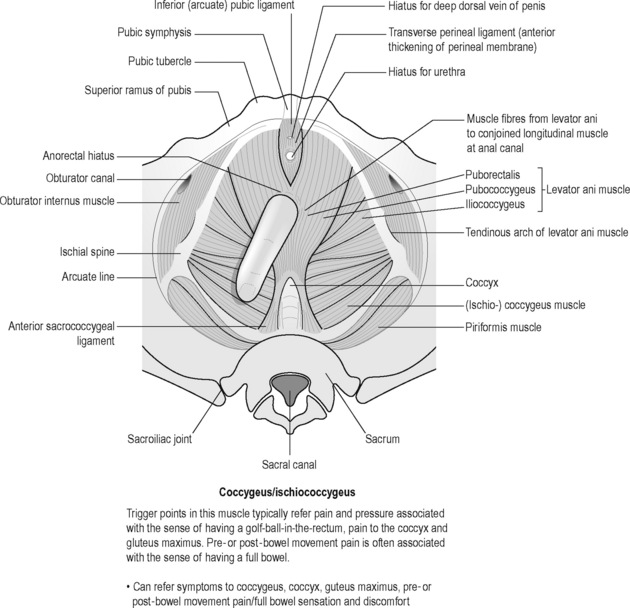

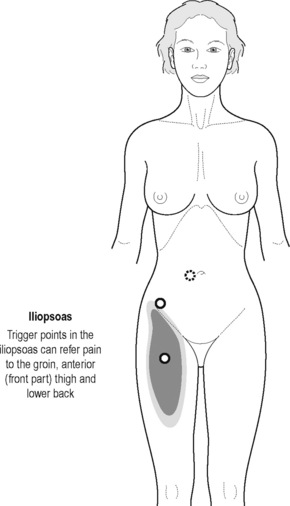

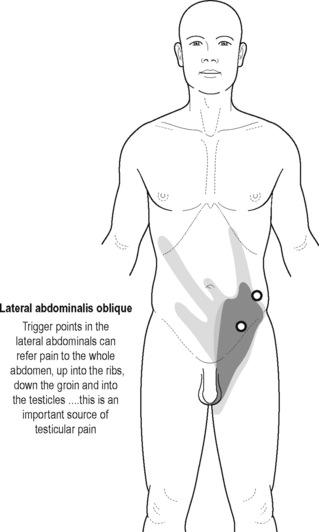

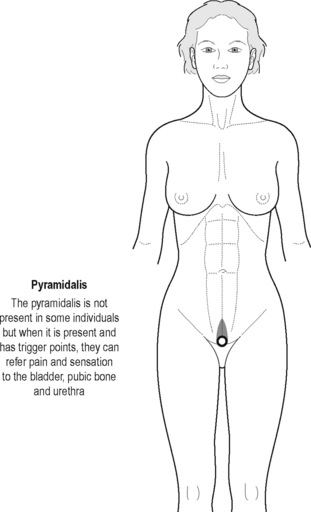

Sinaki believed that the definitive test for the conditions he was reviewing was the digital–rectal examination in which the doctor inserts a gloved lubricated finger into the rectum to feel the state of the muscles. He observed, however, that the normal digital–rectal examination was inadequate to assess the tenderness of the muscles. Figures 12.1–12.5 demonstrate the internal pelvic muscle palpations and typical referral of discomfort when a TrP is involved. Figures 12.6 and 12.7 show typical pain referral patterns from external palpations.

We previously indirectly measured the internal pelvic level of muscle tension via the rectum and vagina of patients consulting us for pelvic pain and dysfunction. Men with PPS show an increased level of pelvic floor muscle tension on EMG. Many women demonstrate weakness and inability to contract pelvic muscles; however, this is only a surface recording of the anal or vaginal muscles not the entire pelvic floor or deeper pelvic muscles around the prostate. There is emerging interest in utilizing behavioural pelvic floor rehabilitation techniques in treating male CPPS. A group from Northwestern University Medical School in Chicago used biofeedback in pelvic floor re-education as well as bladder training for this disorder (Clemens et al. 2000). They recognized that pelvic floor tension myalgia contributes to the symptoms. They studied a small group of 19 men, average age of 36 years, and treated them with this non-interventional process. The men showed improvement, particularly in their urinary scores, but also had a significant decrease in their median pain scores, from 5 to 1 on a scale of 0 (no symptoms) to 10 (worse symptoms). Dr. Howard Glazer reports on his extensive experience utilizing biofeedback in a previous chapter.

The International Association for the Study of Pain defines pain using descriptions and does not address the mechanism of pain. Zermann et al. (2001) found 88% of men with PPS had tender myofascial palpation. Berger et al. (2007) also showed that pelvic tenderness is not limited to the prostate in men with PPS. They studied 62 men with PPS and 98 men without pelvic pain, examining tenderness of ten external pelvic tender points, seven internal pelvic tender points, and other tender points as described by the American College of Rheumatology for evaluation of fibromyalgia. They found 75% of men with PPS had prostate tenderness but so did 50% of normal controls. They also observed no correlation with leucocytosis in expressed prostatic fluid.

Sites of pain have also been recently described for PBS by Warren and colleagues (2008) who hypothesized that careful, systematic analysis of pain experienced by such patients would indicate patterns that might provide clues to pathogenesis. In the 226 women surveyed, 66% reported two or more pain sites; mean of 2.1 sites per patient. Suprapubic prominence and changes in the voiding cycle are consistent with the bladder being the site of pain generation, but do not prove the point. Women with vulvodynia or urethral syndrome do not differ in these pain sites. When specific TrPs are discovered in females, it is feasible to augment myofascial release therapy with TrP injection utilizing local anaesthetic. In a limited study by Langford et al. (2007) 18 women were treated with localized injection and 13 of the 18 women (72%) were improved at 3 months follow-up; six were completely pain-free.

Wise-Anderson Stanford Protocol

After many years of treating patients with UCPPS utilizing both manual physical therapy as well as cognitive behaviour relaxation training, we determined that intensive or immersion therapy over several days was an ideal method to break long-term pain cycles and teach patients to care for themselves. Patients are evaluated as above by a urologist and then immerse themselves into daily physical therapy and paradoxical relaxation training over a 6-day period. We have conducted over 80 monthly sessions of this type, and several months of follow-up (3–24 months) have revealed significant benefit to a large proportion of patients. There has been a significant decrease in NIH-CPSI scores (P < 0.001) and more than 50% of the patients have global response assessments categorized as moderately or markedly improved. In addition a large number of the patients have shown significant psychological benefit (Anderson et al. 2010).

The median age of the 72 men with CPPS in this analysis was 40 years (range 20–72; IQR = 32, 49) with a median duration of symptoms of 44 months (range 4–408 months). The severity of symptoms at the time of the initial examination was measured by the pain VAS (visual analogue scale) score and NIH-CPSI score with higher scores representing greater severity. The median VAS score was 5 out of 10 (range 1–9). The median NIH-CPSI overall score was 27 (43 is the maximum possible) with a median pain domain score of 13 (possible maximum = 21), urinary complaints of 5 (possible maximum = 10) and quality of life score of 10.5 (possible maximum = 12). The median total number of self-reported locations of pain was 4 (IQR = 3, 5) out of a possible 7 pre-designated sites. There was no correlation between pain VAS score and total number of painful locations (R = –0.195; P = 0.11). Furthermore, there was no statistically significant difference in pain VAS score by the presence of pain in any specific location. However, we did find that tenderness in the puborectalis and/or pubococcygeus muscles was associated with a higher pain VAS score (P = 0.013, Mann-Whitney test). Table 12.2 presents the internal and external muscles palpated and how frequently they elicited a painful response. For example, 90.3% (65/72) of men stated that they felt pain associated with palpation of the puborectalis and/or pubococcygeus muscles.

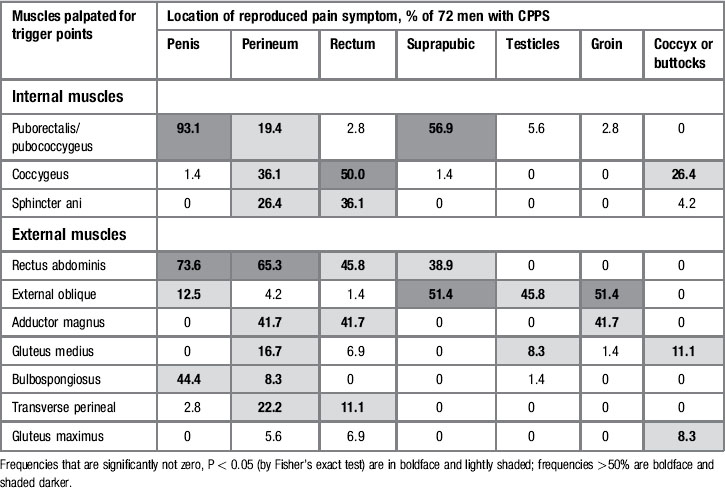

Table 12.2 Frequencies of specific locations of pain elicited by palpation of myofascial trigger points

Painful TrPs, areas of restriction and associated pain location

Table 12.3 presents the muscles palpated and frequencies of referred pain to specific locations, whether or not the patient had initially complained of pain in that anatomical area. For example, palpation of the puborectalis and/or pubococcygeus muscles elicited pain in the penis in 93% (67/72) of the patients. At least two of the ten TrPs could elicit or refer pain to every one of the anatomical sites in a statistically significant proportion of patients (P values determined by the Fisher’s exact test) and every TrP was able to reproduce pain in at least one site. The most reactive muscles were the rectus abdominis and external obliques; palpation of TrPs in these muscles elicited pain in four of the seven sites. Perineal pain was the most reproducible, being elicited by eight out of ten TrPs.

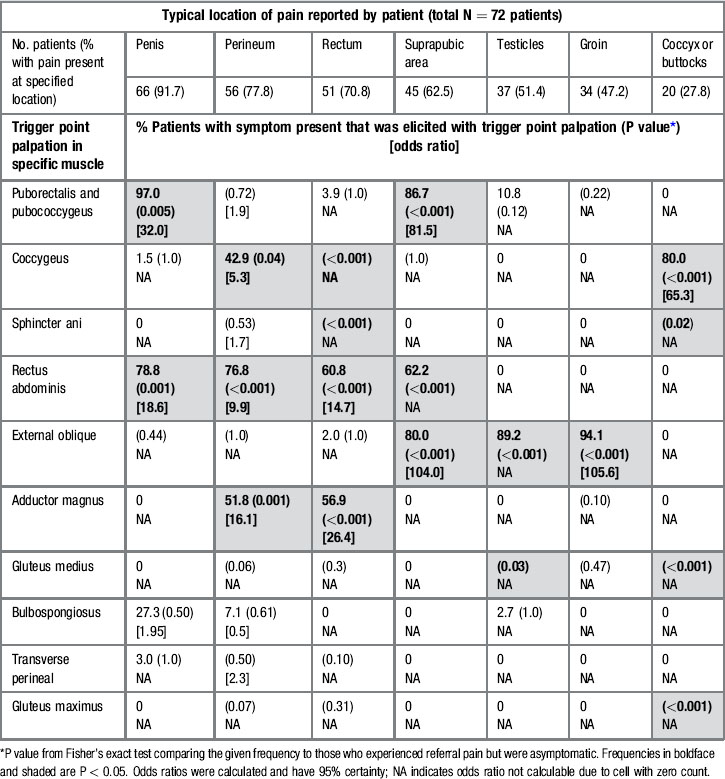

Table 12.3 Frequencies and odds ratios of pain reproduced at specific sites after trigger point palpation among men with CPPS who pre-identified a site of chronic pain

The frequency with which TrP palpation referred pain to a patient’s self-reported chronic pain location is presented in Table 12.3. The odds ratio is shown when calculable. For example, among the 66 patients with penile pain, 64 (97%) experienced this pain after palpation of TrPs in the puborectalis and/or pubococcygeus muscles. The odds ratio of 32.0; 95% CI (2.3, 461.0) implies that these patients were 32 times more likely to have penile pain reproduced with this muscle palpation than patients without penile pain. However, a more conservative interpretation lies with the lower limit of the CI. Thus with 95% certainty, patients with penile pain are at least 2.3 times more likely to have their pain reproduced with this TrP than patients who do not report penile pain. The odds ratio or P value could not be derived in some cases because of zero cell counts. For example, eight of 20 patients (40%) had coccyx or buttocks pain elicited by palpation of the gluteus maximus. None of the patients without coccyx or buttocks pain experienced pain in this location after palpation (0/52 without pain versus 8/20 with pain, P < 0.001, Fisher’s exact test); the odds ratio was not calculable because of the zero cell count. Table 12.3 reveals that pain in each location could be reproduced by at least one TrP in a statistically significant proportion of patients with that prior pain report; rectal and coccyx/buttocks pain were each elicited by four different TrPs. Palpation of the external oblique muscles referred pain to the suprapubic area, testes and groin at least 80% of the time in patients with pain in these locations. Moreover, 80% (8/10) of the TrP palpations reproduced pain in at least one location, and palpation of the rectus abdominis elicited pain in four locations (penis, perineum, rectum and suprapubic area). Repeated palpation of a muscle group had a consistent effect in pain referral. These physical examination findings may lead to greater understanding of pathogenic mechanisms and lead to more focused therapy.

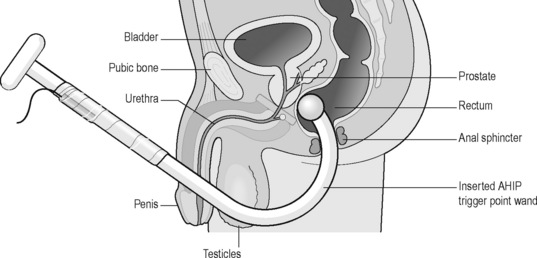

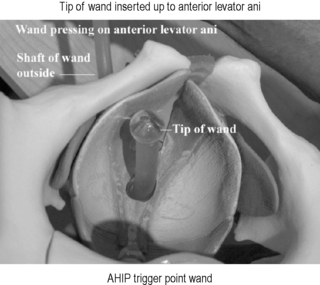

The personal therapeutic wand for chronic pelvic pain

The ideal therapeutic provider combination for care of UCPPS should include a urologist evaluating the urologic signs and symptoms in a systematic fashion, a knowledgeable psychologist to provide psychosocial interpretation, psychological support and cognitive behaviour training such as progressive relaxation therapy and possible medical hypnosis, and a skilled physiotherapist who understands myofascial TrPs, how to release them and how to teach the patient self care. It is not always possible for patients to find follow-up physiotherapy from those who may be appropriately trained and skilled in the techniques required. We have introduced and taught patients self-treatment utilizing a personal therapeutic wand that can be inserted into the rectum or vagina to seek and release TrPs (Figures 12.8–12.10). Previous self-treatment devices have been inadequate to reach appropriate TrPs accurately and safely. Patients are carefully instructed regarding the location of their TrPs and then observed and guided to using the wand within specific pressure ranges to avoid any mucosal trauma or induction of internal tissue damage. These pressures have ranged between 2 and 6 pounds per square inch. Fibromyalgia TrP testing is typically performed at 4 kilograms per square centimetre. In some instances we have been able to train a spouse or significant other to assist in administering the therapeutic wand. Aside from one or two limited minor rectal bleeding episodes, no significant adverse effects have been noted. Patients are prospectively enrolled into a clinical trial under Institutional Review Board approval and followed for a period of 6 months, evaluating safety and efficacy. The intention is to enrol and evaluate 200 patient subjects.

Figure 12.8 • ![]() Illustration of personal massage wand to release trigger points with safety pressure monitoring

Illustration of personal massage wand to release trigger points with safety pressure monitoring

Paradoxical relaxation

An important foundation of the Wise-Anderson Stanford Protocol was established early by Dr. David Wise in an attempt to achieve pelvic floor relaxation effortlessly (Wise 2010). He stated that ‘Paradoxical Relaxation was a method that emerged in the trenches of chronic pain where I closed my own eyes, brought my attention to the inside, and dealt with the question of how I could stop the physical pain and anxiety in which I found myself.’ Nothing that he proposes is theoretical, but shared outcomes from the personal laboratory of his own relaxation practice.

Anderson R.U. Traditional therapy for chronic pelvic pain does not work: what do we do now? Nat. Clin. Pract. Urol.. 2006;3:145-156.

Anderson R.U., Wise D., Sawyer T., et al. Integration of myofascial trigger point release and paradoxical relaxation training treatment of chronic pelvic pain in men. J. Urol.. 2005;174:155-160.

Anderson R.U., Wise D., Sawyer T., et al. Sexual dysfunction in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: Improvement after trigger point release and paradoxical relaxation training. J. Urol.. 2006;176:1534-1539.

Anderson R.U., Orenberg E.K., Chan C.A., et al. Psychometric profiles and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J. Urol.. 2008;179:956-960.

Anderson R.U., Wise D., Sawyer T., Glowe P., Orenberg E. 6-day intensive treatment protocol for refractory chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome using myofascial release and paradoxical relaxation training. J Urology. 2010;185:1294-1299.

Baranowski A.P., Abrams P., Berger R.E., et al. Urogenital pain–time to accept a new approach to phenotyping and, as a consequence, management. Eur. Urol.. 2008;53:33-36.

Berger R.E., Ciol M.A., Rothman I., et al. Pelvic tenderness is not limited to the prostate in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) type IIIA and IIIB: comparison of men with and without CP?/CPPS. Biomedical Center Urology. 2007;7:17.

Clemens J.Q., Nadler R.B., Schaeffer A.J., et al. Biofeedback, pelvic floor re-education, and bladder training for male chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Urology. 2000;56:951-955.

Fall M., Baranowski A.P., Sohier E., et al. EAU guidelines on chronic pelvic pain. Eur. Urol.. 2010;57:35-48.

Fitzgerald M.P., Anderson R.U., Potts J., et al. Randomized multicenter feasibility trial of myofascial physical therapy for the treatment of urological chronic pelvic pain syndromes. J. Urol.. 2009;182:570-580.

Geramoutsos I., Gyftopoulos K., Perimenis P., et al. Clinical correlation of prostatic lithiasis with chronic pelvic pain syndromes in young adults. Eur. Urol.. 2004;45:333-337.

Hafez H. Urodynamic evaluation of patients with chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Urotoday International Journal. 2009:2.

Hanno P., Lin A., Nordling J., et al. Bladder pain syndrome international consultation on incontinence. Neurourol. Urodyn.. 2010;29:191-198.

Heidenreich A., Olbert P., Engelmann U.H. Management of chronic testalgia by microsurgical testicular denervation. Eur. Urol.. 2002;41:392-397.

Hetrick D.C., Glazer H., Liu Y.W., et al. Pelvic floor electromyography in men with chronic pelvic pain syndrome: A case-control study. Neurourol. Urodyn.. 2006;25:46-49.

Hori S., Sengupta A., Shuklaw C.J., et al. Long-term outcome of epidiymectomy for the management of chronic epididymal pain. J. Urol.. 2009;182:1407-1412.

Langford C.F., Nagy S.U., Ghomeim G.M. Levator ani trigger point injections: An underutilized treatment for chronic pelvic pain. Neurourol. Urodyn.. 2007;26:59-62.

Lee J.C., Yang C.C., Kromm B.G., et al. Neurophysiologic testing in chronic pelvic pain syndrome: A pilot study. Urology. 2001;58:246-250.

Levine L.A., Matkov T.G. Microsurgical denervation of the spermatic cord as primary surgical treatment of chronic orchialgia. J. Urol.. 2001;165:1927-1929.

McJunkin T.L., Wuollet A.L., Lynch P.J. Sacral nerve stimulation as a treatment modality for intractable neuropathic testicular pain. Pain Physician. 2009;12:991-995.

Nickel J.C., Shoskes D.A., Irvine-Brid K. Clinical phenotyping of women with interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome: A key to classification and potentially improved management. J. Urol.. 2009;182:155-160.

Planken E., Voorham van der Zaim P.J., Lycklama Nijeholt A.B., et al. Chronic testicular pain as a symptom of pelvic floor dysfunction. J. Urol.. 2010;183:177-181.

Schaeffer A.J., Knauss J.S., Landis J.R., et al. Leukocyte and bacterial counts do not correlate with severity of symptoms in men with chronic prostatitis: The National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis cohort study. J. Urol.. 2002;168:1048-1053.

Shoskes D.A., Zeitlin S.I. Use of prostate massage in combination with antibiotics in the treatment of chronic prostatitis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis.. 1999;2:159-162.

Shoskes D.A., Lee C.T., Murphy D., et al. Incidence and significance of prostatic stones in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Urology. 2007;70:235-238.

Shoskes D.A., Nickel J.C., Dolinga R., et al. Clinical phenotyping of patients with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome and correlation with symptom severity. Urology. 2009;73:538-542.

Stav K., Dwyer P.L., Roberts L. Pudendal neuralgia fact or fiction? Obstet. Gynecol. Surv.. 2009;64:190-199.

Strohmaier W.L., Bichler K.H. Comparison of symptoms, morphological, microbiological and urodynamic findings in patients with chronic prostatitis/pelvic pain syndrome. Is it possible to differentiate separate categories? Urol. Int.. 2000;65:112-116.

Sweeney C.A., Oades G.M., Fraser M., et al. Does surgery have a role in management of chronic intrascrotal pain? Urology. 2008;71:1099-1102.

Warren J.W., Langenberg P., Greenberg P., et al. Sites of pain from interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. J. Urol.. 2008;180:1373-1377.

Weiss J.M. Pelvic floor myofascial trigger points: Manual therapy for interstitial cystitis and the urgency-frequency syndrome. J. Urol.. 2001;166:2226-2231.

Wise D. Paradoxical relaxation. In Wise D., Anderson R.U., editors: A Headache In The Pelvis: A new understanding and treatment for chronic pelvic pain syndromes, sixth ed., Sebastapol, CA: National Center for Pelvic Pain, 2008.

Zermann D.H., Ishigooka M., Doggweiler-Wiygul R., et al. The male chronic pelvic pain syndrome. World J. Urol.. 2001;19:173-179.