CHAPTER 143 Esthesioneuroblastoma

Esthesioneuroblastoma, first described by Berger, Luc, and Richard in 1924,1 is an uncommon neoplasm that arises from olfactory epithelium high in the nasal vault and frequently invades the skull base, cranial vault, and orbit. Although esthesioneuroblastoma accounts for up to 3% of intranasal neoplasms in some series, fewer than 400 unique cases have been reported in the world literature. The recent apparent increase in incidence is at least in part attributable to improvements in diagnostic imaging and pathologic recognition of this relatively rare entity. Because of the limited number of subjects treated in different eras of medical and surgical practice, in addition to nonuniform treatment schemes and follow-up, management recommendations regarding these tumors have been based largely on anecdotal data and limited series.

Pathology

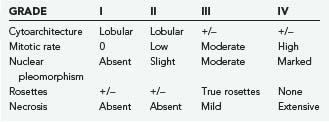

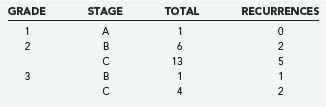

The morphologic, ultrastructural, and immunohistochemical features of esthesioneuroblastoma are similar to those of neuroblastoma of the adrenal glands and sympathetic nervous system. Light microscopy reveals a lobular architecture with sheets of cells in a dense neurofibrillary background. Individual cells have round to oval nuclei with scant, poorly defined cytoplasm. Occasionally, olfactory rosettes or pseudorosettes are present. A grading system based on histology has been proposed as a prognostic tool but has achieved varying success (Table 143-1) (Fig. 143-1).2

Ultrastructurally, dense membrane-bound neurosecretory granules are seen along with neurofilaments and microtubules. On immunohistochemical staining, most esthesioneuroblastomas are positive for neuron-specific enolase (NSE), neurofilament, synaptophysin, chromogranin, and Leu-7 and variably positive for S-100. Although similar to neuroblastoma histologically, correlated coexpression of NSE and cytokeratin points to an epithelial rather than neural crest origin of these tumors.3

Clinical Findings

Patients with esthesioneuroblastoma are typically evaluated by the otolaryngologist for complaints of nasal obstruction or recurrent epistaxis. A fleshy, friable nasal mass is frequently noted, and hyposmia is often detected on formal testing. Other, less common initial symptoms and signs include headache, visual impairment, and rhinorrhea (Table 143-2). Males and females are affected equally.4–6 The age at diagnosis has been reported to be 3 to 78 years with a bimodal distribution consisting of peaks in the second and fifth decades.7,8 No geographic, environmental, or lifestyle risk factors have been clearly associated with increased risk for esthesioneuroblastoma.

TABLE 143-2 Initial Symptoms and Signs of Esthesioneuroblastoma

| Nasal Obstruction |

| Epistaxis |

| Nasal mass |

| Hyposmia |

| Headache |

| Rhinorrhea |

| Visual acuity loss |

| Proptosis |

| Mental status changes |

| Neck mass |

| Tooth pain |

| Face pain |

| Face mass |

| Diplopia |

Metastatic disease is present in 17% to 48% of patients with esthesioneuroblastoma at diagnosis.9–12 Cervical lymph nodes account for the majority of metastases; other locations include lung, bone, and much less commonly, liver, mediastinum, adrenal gland, ovary, spleen, parotid, central nervous system, and spinal epidural space.6,13 In our experience, 8% of patients in whom esthesioneuroblastoma was detected had metastatic disease in the cervical lymph nodes, with cervical node disease eventually developing in 28%. Metastatic disease ultimately developed in some location in 37% of patients.

Patient Evaluation

Preoperative evaluation includes a thorough history and physical examination to determine the extent of the symptoms and concomitant medical conditions that might limit aggressive management. Evaluation by an otolaryngologist is warranted both to assess the extent of sinus and cervical disease and to provide a diagnostic biopsy specimen. A preoperative neuro-ophthalmologic evaluation should be performed to identify visual acuity or motility deficits and to document baseline function in patients with disease near orbital structures or in whom extensive surgical resection is anticipated (Table 143-3).

TABLE 143-3 Preoperative Evaluation of Patients with a Suspected Sinonasal Mass

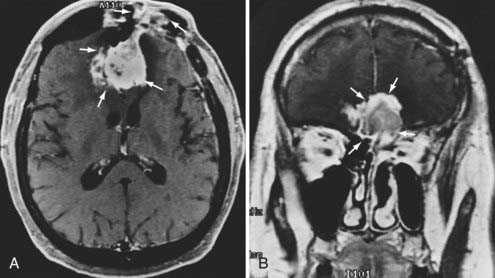

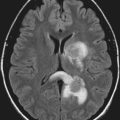

Radiographic assessment of tumor begins with contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT). Sinus disease and bony erosion are well depicted by CT. Erosion of the floor of the anterior fossa or orbital wall is common, and in such cases magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is of utility in more clearly depicting the extent of soft tissue disease and better visualizing pathology near the orbital apex (Fig. 143-2). However, when the bone erosion depicted on CT is minimal, MRI is still strongly recommended because the extent of intracranial disease may be significant even with little visualized bony involvement. Adequate radiographic assessment allows preoperative classification of the tumor according to the scheme proposed by Kadish and modified by others (Table 143-4).12,14,15 As discussed later, this system has been correlated with outcome with some reliability.

TABLE 143-4 Modified Kadish Staging of Esthesioneuroblastoma

| Stage A | Tumor confined to the nasal cavity |

| Stage B | Tumor extension to the paranasal sinuses |

| Stage C | Tumor beyond the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, including involvement of the cribriform plate, base of the skull, intracranial cavity, and/or orbit |

| Stage D | Tumor with metastases to the cervical lymph nodes and/or distant sites |

Treatment

Radiotherapy

Early lesions (Kadish stage A or B) have been managed successfully with radiation therapy alone in some cases; Elkton and coauthors reported short-term local tumor control with radiation therapy alone in 17 of 21 stage A or B tumors.16 Their findings have been confirmed by others,17 but some have suggested that the use of radiation as a sole treatment modality be reserved for inoperable cases.7,18 Anecdotal, unpublished cases of smaller tumors limited to the nasal cavity and successfully treated exclusively with biopsy and radiosurgery have been reported, although experience with this scheme is inadequately detailed and limited by short-term follow-up. However, based on our experience with the use of radiosurgery for focal areas of recurrent disease, primary definitive radiosurgery may be a valid plan for stage A and selected stage B tumors.

Preoperative radiotherapy has also been recommended. Theoretical benefits of preoperative radiation therapy include decreasing tumor mass and minimizing local tumor dissemination and distant metastases at the time of surgery by decreasing cell viability. Preoperative tumor irradiation has proved useful in sparing the orbital contents during surgery for paranasal sinus carcinoma.19 In doses of 50 to 60 Gy, radiation therapy has also been purported to decrease the likelihood of tumor recurrence. In a series from the Mayo Clinic, the incidence of recurrence of both high- and low-grade tumors was reduced by postoperative radiation treatment.8 A review of the recent literature revealed that just 20% of patients treated by radiotherapy and surgery had recurrence of tumor at 5 years versus 50% who underwent surgery alone. For patients with advanced or metastatic disease, adjuvant therapy may provide additional benefit. Improved outcomes have been reported for patients undergoing neck dissection and radiation therapy for cervical disease.5,20

Chemotherapy

Histologically and ultrastructurally, esthesioneuroblastoma shares features with other chemosensitive tumors such as neuroblastoma, small cell lung carcinoma, and primitive neuroectodermal tumor. Probably for this reason, similar chemotherapeutic regimens found to be effective for these other lesions have been used for esthesioneuroblastoma, with variable results. In one series of 7 patients, chemotherapy induced a partial response in 4 patients and no response in 3.6 Another study reported improvement after chemotherapy in 19 of 20 patients.21 A series from the Mayo Clinic demonstrated regression of disease after chemotherapy in 2 of 4 patients with Hyams’ grade III or grade IV tumors but in none of the 4 with lower grade lesions.22 Gross total tumor resection combined with chemotherapy has produced better outcomes than chemotherapy alone has, but this is confounded by the fact that patients who did not undergo attempted resection had more extensive disease at diagnosis. Typically, regimens include cyclophosphamide and vincristine, although doxorubicin is sometimes included. Platinum-based therapies have also been used with some favorable results. A few centers have used high-dose chemotherapy with bone marrow rescue and intra-arterial chemotherapy with some success as well.23–26

Combined Chemoradiation Therapy

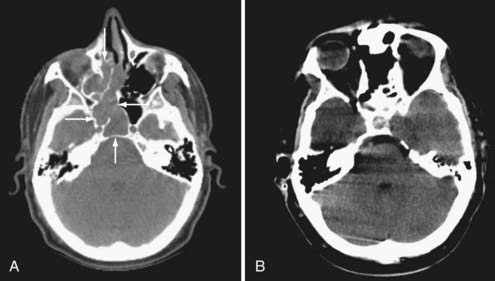

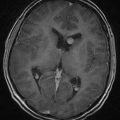

At the University of Virginia and Penn State University, we have routinely used preoperative radiation therapy and chemotherapy for our patients with esthesioneuroblastoma. Patients with Kadish stage A or B tumors received 45 to 50 Gy of radiation preoperatively; patients with Kadish stage C lesions underwent the same dose of radiation in addition to six cycles of cyclophosphamide-vincristine (20 patients) or cisplatin-etoposide (3 patients) chemotherapy. We have retrospectively analyzed pretreatment and posttreatment MRI findings in 24 patients. Our treatment regimen was associated with a decrease in total tumor volume of greater than 50% or a reduction in intracranial tumor mass of greater than 90% in 13 patients (54%). Total tumor volume reduction of 20% to 50% was seen in 4 patients (17%). Six patients (25%) showed no response (Fig. 143-3). Interestingly, the only patient with progression of tumor during the period of chemoradiation therapy received methotrexate instead of cyclophosphamide.

Surgical Resection

Surgical resection has been the mainstay of therapy for esthesioneuroblastoma despite reports of local tumor control with adjuvant treatment alone. In patients not medically precluded from surgery, resection appears to improve long-term results. Smith and colleagues described a combined transfacial and transcranial approach for resection of paranasal sinus carcinoma in 1954,27 and in 1970, the first craniofacial resection for esthesioneuroblastoma was performed by Drs. Slaughter Fitz-Hugh and John Jane at the University of Virginia. Soon thereafter, boosted by the reports of Ketcham and associates and Clifford, the use of craniofacial resection for tumors in this region became widespread.28,29 This era fostered development of the “craniofacial team” concept, in which members of the neurosurgical, ear, nose, and throat, and ophthalmologic disciplines are incorporated. The limits of tumor resection were extended, and improvements in outcome followed.30–33 At our institution, 5-year disease-free survival rates improved from 37% to 82% with the advent of a craniofacial approach to these tumors.11 In our experience and that of others, patients undergoing gross total tumor resection had a statistically significant improvement in outcome over those who underwent biopsy and radiation therapy.6 However, this analysis is confounded by the more advanced stage of disease in those selected to undergo the less invasive treatment option. Our experience at the University of Virginia with 50 patients showed disease-free survival rates of 86.5% and 82.6% at 5 and 15 years, respectively.34

Radiosurgery

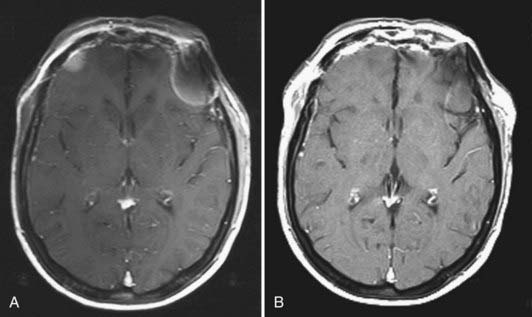

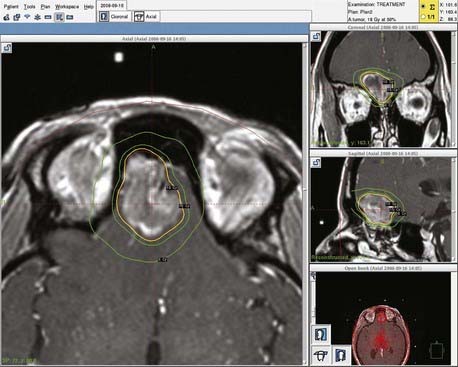

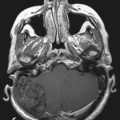

Experience with stereotactic radiosurgery for esthesioneuroblastoma is limited to a few anecdotal reports. No published reports of definitive (primary) radiosurgery for esthesioneuroblastoma exist. However, published reports have demonstrated success with radiosurgical treatment of recurrent or residual disease.35 Our personal experience with recurrent disease confirms that esthesioneuroblastomas are responsive to radiosurgery and that this technique merits further exploration for these tumors (Fig. 143-4). Radiosurgery may be complicated by the difficulty of determining an accurate target in the setting of postoperative changes, including extensive packing for cranial base reconstruction. In addition, doses may be limited by the proximity of the target volume to the optic nerves and chiasm (Fig. 143-5). When postoperative radiosurgery is anticipated, clearance of tumor from the area near the optic apparatus should be attempted to aid planning of the radiosurgical dose.

Surgical Technique

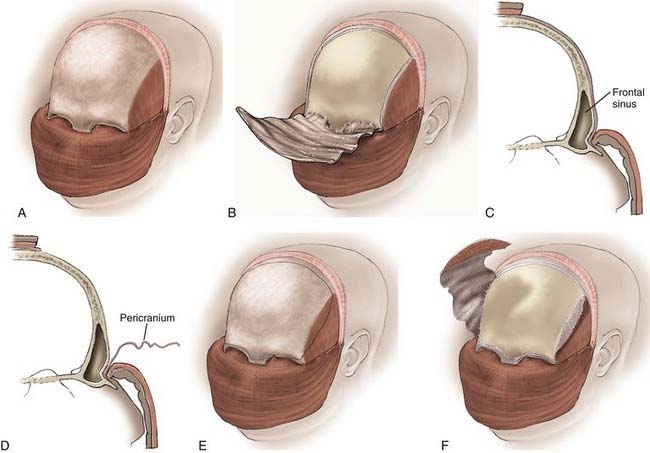

The transcranial portion of the procedure is accomplished through a bicoronal incision. The scalp and galea are initially reflected inferiorly to the level of the orbital rims while leaving the pericranium intact. The pericranial flap is based inferiorly along the brow line, and the posterior part of the scalp incision can be undermined to provide a larger pericranial flap if a large anterior fossa floor defect is anticipated (Fig. 143-6).

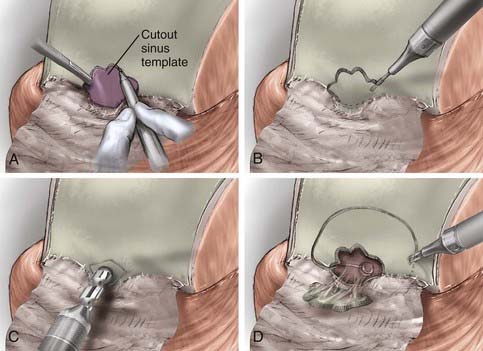

The inferior portion of the flap involves the frontal sinus, and there are several methods to enter and address the frontal sinus during this portion of the exposure. When the frontal sinus is small, a bur hole may be placed at the glabella to provide entry into the sinus; this site is then covered with a bur hole microplate at closure for cosmesis. In patients with more pneumatized frontal sinuses, a preoperative 6-ft Caldwell skull film can be used to create a cutout template of the frontal sinus. The template is sterilized and placed in position, and the edge of the sinus is traced (Fig. 143-7). Another alternative involves using the non-footplate drill guard and a pediatric side-cutting craniotomy bit to drill through the anterior wall of the sinus and then elevate the frontal bone flap and “crack” the posterior wall of the sinus. A more recent alternative is the use of a frameless image guidance system to delineate the extent of the frontal sinus. (The use of image guidance has been especially helpful in patients with extensive involvement of the anterior fossa floor and facilitates identification of the optic canals through extensive disease.) A thin side-cutting drill bit is then used to perforate the anterior wall of the frontal sinus along its periphery and detach any bony intrasinus septa. The anterior wall of the frontal sinus is next removed to provide entry into the sinus, and the mucosa of the frontal sinus is exenterated. The dura is exposed with the use of a drill and a rongeur to remove the posterior wall of the sinus. In a patient with a well-pneumatized sinus and no appreciable intracranial extension of tumor, the frontal sinus itself provides adequate exposure. If additional exposure is necessary, a single bur hole is placed on the midline of the frontal bone and a craniotomy is turned down to the orbital rim bilaterally and across the brow line (Fig. 143-7).

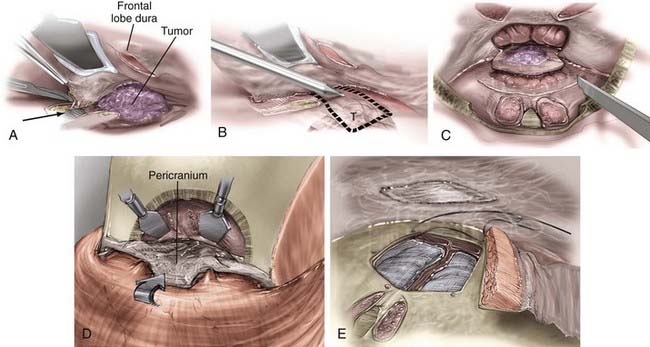

The dura over the medial orbital roof and midline is elevated, and the crista galli is removed. The anterior ethmoidal arteries are coagulated and divided. Next, the dural coverings of the olfactory fibers are identified as they pass through the cribriform plate and sharply divided as close to the cribriform as possible. When the last of these coverings is divided, epidural dissection can be continued posteriorly as far as necessary. Cutting of these dural coverings leaves two parallel linear openings in the dura, which allows CSF to drain temporarily, if necessary. After verifying hemostasis of the intracranial ends of the cut fibers, the dura is closed primarily with a watertight continuous stitch. If the tumor has extended through the dura, the intracranial portion of the tumor and involved dura are removed. Radical removal is indicated and extensive dural grafting is often necessary. A number of dural graft options are available to assist in closure by suturing the graft to the remaining dural edge in watertight fashion to close such a defect (Fig. 143-8).

More recently, authors have described success with a combination of endoscopic sinus surgery and stereotactic radiosurgery for the treatment of esthesioneuroblastoma.35 Given the frequent extensive sinus disease, total oncologic resection via the endoscope is unlikely, but the potency of radiosurgery may provide adequate control of residual disease in patients in whom the area of concern is not immediately adjacent to the optic nerves or chiasm, which would limit the allowable treatment dose that can be delivered. We have had success in treating residual or recurrent disease in four patients with Gamma Knife radiosurgery; however, follow-up at this time remains limited.

Complications

Complications in the treatment of esthesioneuroblastoma are usually due to radiation therapy and surgical intervention. In our experience and that of others, blindness secondary to radiation- induced optic neuropathy, retinopathy, or keratoconjunctivitis has not been seen.8 However, the doses used are sufficient to lead to a low incidence of delayed visual deterioration. In addition, we have not experienced radiation-related problems with wound healing in patients preoperatively treated with radiotherapy, although this risk certainly exists and problems have been reported by others. Surgical complications are also infrequent. Cerebral infarction and contusion, CSF leakage, epidural abscess, meningitis, bone flap infection requiring flap removal, and visual complications such as blindness, loss of acuity, diplopia, and exophthalmos have been reported.6,7,36 Two of our patients suffered infections requiring bone flap removal, and one had an epidural abscess. There were no cases of meningitis, and hyponatremia was seen in one patient. Chemotoxic complications at our institution have included bone marrow suppression, vocal cord paralysis, peripheral neuropathy, and herpes zoster infection, each in one patient.

Outcomes

Attempts have been made to correlate outcome in patients with esthesioneuroblastoma to age, gender, clinical findings, stage, and histologic grade.2,12,16,37–39 Unfortunately, the small number of subjects has limited the consistency and significance of these relationships. Some authors have suggested that female gender or age older than 50 years predicts a worse course; others have disagreed.6,7,15 No strong correlation between initial symptoms and outcome has been made.

Several authors have suggested that pathologic grade may be related to outcome.2,8,37,39 Patients with higher grade tumors may be more likely to have recurrent and metastatic disease and to die of disease progression. Other investigators have found no reliable relationship between grade and clinical behavior of the tumor.9,38,40,41 Our patients with Hyams’ grade II histology demonstrated an 86% 5-year survival rate versus only 58% for patients with grade III lesions; however, because of the small sample size, no statistically significant correlation could be made.

Tumor stage has been proposed as a prognostic factor as well.12,16 Goldsweig and Sundaresan found that the extent of disease and the degree of resectability of the mass were related to outcome,21 and many authors have found that lower stage tumors have longer disease-free survival and fewer recurrences than do more advanced tumors.6,7,42 At the University of Virginia, no patients with Kadish stage A or B tumors died of esthesioneuroblastoma, whereas 7 of 26 patients with stage C disease did (average follow-up of 8 years). No tumor recurrence was seen in 9 of 11 patients with stage A and stage B lesions as opposed to 15 of 26 patients with stage C tumors. Patients with metastatic disease have been found to have a worse clinical course than those with local disease only, and those with disease beyond the cervical lymph nodes rarely survive more than 1 year. However, others have found no relationship between the extent of local or metastatic disease and outcome.15 Blurring the distinction between the significance of grade and stage is the fact that they are intimately interrelated; patients with higher grade, more aggressive tumors generally have more advanced disease at initial evaluation.

In a series of 25 patients who received their entire course of treatment at our institution, we have not found histologic grade to be of more prognostic significance than disease stage. There were 19 patients with grade 2 pathology and 5 patients with grade 3. Of the grade 2 patients, 6 were stage B, 2 of whom experienced recurrence of disease; 5 of the 13 grade 2, stage C tumors recurred. For grade 3 tumors, the lone stage B tumor recurred, as did 2 of the 4 stage C tumors. The only grade 1 tumor has not recurred (Table 143-5).

Beitler JJ, Fass DE, Brenner HA, et al. Esthesioneuroblastoma: is there a role for elective neck treatment? Head Neck. 1991;13:321-326.

Berger L, Luc H, Richard A. L’esthesioneuroepitheliomeolfactif. Bull Assoc Franc Etude Cancer. 1924;13:410-421.

Cantrell RW. Esthesioneuroblastoma. In: Sekhar LN, Janecka IP, editors. Surgery of Cranial Base Tumors. New York: Raven Press; 1993:471-476.

Cantrell RW, Ghorayeb BY, Fitz-Hugh GS. Esthesioneuroblastoma: diagnosis and management. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1977;86:760-765.

Castaneda VL, Cheah MS, Saldivar VA, et al. Cytogenetic and molecular evaluation of clinically aggressive esthesioneuroblastoma. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1991;13:62-70.

Dulguerov P, Calcaterra T. Esthesioneuroblastoma: the UCLA experience 1970-1990. Laryngoscope. 1992;102:843-849.

Goldsweig HG, Sundaresan N. Chemotherapy of recurrent esthesioneuroblastoma: case report and review of the literature. Am J Clin Oncol. 1990;13:139-143.

Hyams VJ. Tumors of the upper respiratory tract and ear. In: Hyams VJ, Batsakis JG, Michaels L, editors. Atlas of Tumor Pathology, Second Series, Fascicle 25. Washington DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1988:240-248.

Kadish S, Goodman M, Wang CC. Olfactory neuroblastoma: a clinical analysis of 17 cases. Cancer. 1976;37:1571-1576.

Levine PA, Debo RF, Meredith SD, et al. Craniofacial resection at the University of Virginia (1976-1992): survival analysis. Head Neck. 1994;16:574-577.

Loy AH, Reibel JF, Read PW, et al. Esthesioneuroblastoma: continued follow-up of a single institution’s experience. Arch Otol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:134-138.

McElroy EA, Buckner JC, Lewis JE. Chemotherapy for advanced esthesioneuroblastoma: the Mayo Clinic experience. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:1023-1028.

Mills SE, Frierson HF. Olfactory neuroblastoma: a clinicopathologic study of 21 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985;9:317-327.

O’Connor GT, Drake CR, Johns ME, et al. Treatment of advanced esthesioneuroblastoma with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous bone marrow transplantation: a case report. Cancer. 1985;55:347-349.

Perry CF, Levine PA, Williamson BR, et al. Preservation of the eye in paranasal sinus cancer surgery. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988;114:632-634.

Polin RS, Sheehan JP, Chenelle AG, et al. The role of pre-operative adjuvant treatment in the management of esthesioneuroblastoma: the University of Virginia experience. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:1029-1037.

Richtsmeier WJ, Briggs RJ, Koch WM, et al. Complications and early outcome in anterior craniofacial resection. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118:913-917.

Scher RL, Richtsmeier WJ. Craniofacial resection of anterior skull base tumors. In: Wilkins RH, Rengachary SS, editors. Neurosurgery. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1996:1603-1610.

Stewart FM, Lazarus HM, Levine PA, et al. High-dose chemotherapy and autologous marrow transplantation for esthesioneuroblastoma and sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 1989;12:217-221.

Unger F, Haselsberger K, Walch C, et al. Combined endoscopic surgery and radiosurgery as treatment modality for olfactory neuroblastoma (esthesioneuroblastoma). Acta Neurochir. 2005;147:595-602.

1 Berger L, Luc H, Richard A. L’esthesioneuroepitheliomeolfactif. Bull Assoc Franc Etude Cancer. 1924;13:410-421.

2 Hyams VJ. Tumors of the upper respiratory tract and ear. In: Hyams VJ, Batsakis JG, Michaels L, editors. Atlas of Tumor Pathology, Second Series, Fascicle 25. Washington DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1988:240-248.

3 Banerjee AK, Sharma BS, Vashishta RK, et al. Intracranial olfactory neuroblastoma: evidence for olfactory epithelial origin. J Clin Pathol. 1992;45:299-302.

4 Cantrell RW. Esthesioneuroblastoma. In: Sekhar LN, Janecka IP, editors. Surgery of Cranial Base Tumors. New York: Raven Press; 1993:471-476.

5 Zappia JJ, Carroll WR, Wolf GT, et al. Olfactory neuroblastoma: the results of modern treatment approaches at the University of Michigan. Head Neck. 1993;15:190-196.

6 Morita A, Ebersold MJ, Olsen KD, et al. Esthesioneuroblastoma: prognosis and management. Neurosurgery. 1993;32:706-715.

7 Polin RS, Sheehan JP, Chenelle AG, et al. The role of pre-operative adjuvant treatment in the management of esthesioneuroblastoma: the University of Virginia experience. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:1029-1037.

8 Ebersold MJ, Olsen KD, Foote RL, et al. Esthesioneuroblastoma. In: Kaye AH, Laws ER, editors. Brain Tumors. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1997:825-838.

9 Bailey BJ, Barton S. Olfactory neuroblastoma, management and prognosis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1975;101:1-5.

10 Cantrell RW, Ghorayeb BY, Fitz-Hugh GS. Esthesioneuroblastoma: diagnosis and management. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1977;86:760-765.

11 Levine PA, McLean WC, Cantrell RW. Esthesioneuroblastoma: the University of Virginia experience. Laryngoscope. 1985;96:742-746.

12 Kadish S, Goodman M, Wang CC. Olfactory neuroblastoma: a clinical analysis of 17 cases. Cancer. 1976;37:1571-1576.

13 Castaneda VL, Cheah MS, Saldivar VA, et al. Cytogenetic and molecular evaluation of clinically aggressive esthesioneuroblastoma. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1991;13:62-70.

14 Biller HF, Lawson W, Sachdev VP, et al. Esthesioneuroblastoma: surgical treatment without radiation. Laryngoscope. 1990;100:1199-1201.

15 Dulguerov P, Calcaterra T. Esthesioneuroblastoma: the UCLA experience 1970-1990. Laryngoscope. 1992;102:843-849.

16 Elkton D, Hightower SI, Lim ML, et al. Esthesioneuroblastoma. Cancer. 1979;44:1087-1094.

17 Obert GJ, Devine KD, MacDonald JR. Olfactory neuroblastomas. Cancer. 1960;13:205-215.

18 Djalilian M, Zujko RD, Weiland LH, et al. Olfactory neuroblastoma. Surg Clin North Am. 1977;57:751-762.

19 Perry CF, Levine PA, Williamson BR, et al. Preservation of the eye in paranasal sinus cancer surgery. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988;114:632-634.

20 Beitler JJ, Fass DE, Brenner HA, et al. Esthesioneuroblastoma: is there a role for elective neck treatment? Head Neck. 1991;13:321-326.

21 Goldsweig HG, Sundaresan N. Chemotherapy of recurrent esthesioneuroblastoma: case report and review of the literature. Am J Clin Oncol. 1990;13:139-143.

22 McElroy EA, Buckner JC, Lewis JE. Chemotherapy for advanced esthesioneuroblastoma: the Mayo Clinic experience. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:1023-1028.

23 Nguyen QA, Villablanca JG, Siegel SE, et al. Esthesioneuroblastoma in the pediatric age group: the role of chemotherapy and autologous bone marrow transplantation. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1996;37:45-52.

24 O’Connor GT, Drake CR, Johns ME, et al. Treatment of advanced esthesioneuroblastoma with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous bone marrow transplantation: a case report. Cancer. 1985;55:347-349.

25 Watney K, Hager B. Treatment of recurrent esthesioneuroblastoma with combined intra-arterial chemotherapy: a case report. J Neurooncol. 1987;5:47-50.

26 Stewart FM, Lazarus HM, Levine PA, et al. High-dose chemotherapy and autologous marrow transplantation for esthesioneuroblastoma and sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 1989;12:217-221.

27 Smith RR, Klopp CT, Williams LM. Surgical treatment of cancer of the frontal sinus and adjacent areas. Cancer. 1954;7:991-994.

28 Ketcham AS, Chretien PB, Van Buren JM, et al. The ethmoid sinuses: a re-evaluation of surgical resection. Am J Surg. 1973;126:469-476.

29 Clifford P. Transcranial approach to cancer of the anteroethmoid area. Clin Otolaryngol. 1977;2:115-130.

30 Levine PA, Frierson HF, Stewart FM, et al. Sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma: a distinctive and highly aggressive neoplasm. Laryngoscope. 1987;97:905-908.

31 Richtsmeier WJ, Briggs RJ, Koch WM, et al. Complications and early outcome in anterior craniofacial resection. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118:913-917.

32 Shah JP, Sundaresan N, Galicich J, et al. Craniofacial resection for tumors involving the base of the skull. Am J Surg. 1987;154:352-358.

33 Schramm VL, Myers EN, Maroon JC. Anterior skull base surgery for benign and malignant disease. Laryngoscope. 1979;89:1077-1091.

34 Loy AH, Reibel JF, Read PW, et al. Esthesioneuroblastoma: continued follow-up of a single institution’s experience. Arch Otol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:134-138.

35 Unger F, Haselsberger K, Walch C, et al. Combined endoscopic surgery and radiosurgery as treatment modality for olfactory neuroblastoma (esthesioneuroblastoma). Acta Neurochir. 2005;147:595-602.

36 Scher RL, Richtsmeier WJ. Craniofacial resection of anterior skull base tumors. In: Wilkins RH, Rengachary SS, editors. Neurosurgery. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1996:1603-1610.

37 McCormack LJ, Harris HE. Neurogenic tumors of the nasal fossa. JAMA. 1955;157:318-321.

38 Mills SE, Frierson HF. Olfactory neuroblastoma: a clinicopathologic study of 21 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985;9:317-327.

39 Silva EG, Butler JJ, Mackay B, et al. Neuroblastomas and neuroendocrine carcinomas of the nasal cavity: a proposed new classification. Cancer. 1982;50:2388-2405.

40 Lewis JS, Hunter RV, Toffelson HR, et al. Nasal tumors of olfactory origin. Arch Otolaryngol. 1965;81:169-174.

41 Oberman HA, Dale HR. Olfactory neuroblastoma: a clinicopathologic study. Cancer. 1976;38:2494-2502.

42 Levine PA, Debo RF, Meredith SD, et al. Craniofacial resection at the University of Virginia (1976-1992): survival analysis. Head Neck. 1994;16:574-577.