Chapter 75B Esophageal varices

Acute management of portal hypertension

Overview

The most important aspect of care in patients with suspected variceal or other portal hypertensive hemorrhage is adequate resuscitation while directed diagnostic maneuvers and therapies are being coordinated. Although this chapter focuses on acute esophageal variceal bleeding, many of the principles and therapies may apply to other sources of portal hypertensive bleeding. Acute variceal hemorrhage is associated with a 15% to 20% mortality rate at 6 weeks (Abraldes et al, 2008; Villanueva et al, 2006). Although evidence supports the use of endoscopy for diagnosis and treatment, insufficient resuscitation can lead to significant periprocedural complications. Appropriate pharmacotherapy has proven equally effective in controlling variceal hemorrhage in some studies. More importantly, pharmacotherapy can be started immediately in any hospital, regardless of endoscopic staff availability.

The morbidity of patients who present with acute variceal hemorrhage is strongly influenced by their reason for recent decompensation. In most instances, early resuscitative measures followed by pharmacotherapy and endoscopy allow improvement in hepatic synthetic function and provide time to address more definitively the overall management of the patient and any recurrent bleeding. In patients with life-threatening exsanguination, balloon tamponade is a useful maneuver until the patient is stable enough for endoscopy. In patients with bleeding refractory to pharmacotherapy and endoscopic intervention, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting (TIPS) generally is the next option for short- and mid-term stabilization (see Chapter 76E). Shunt operations (see Chapters 76A through 76D) have traditionally been reserved for individuals for whom transplantation and TIPS are not an option but who have a reasonable chance of operative survival.

Emergency Management

Before any diagnostic maneuvers can be performed (e.g., endoscopy), support of the circulating blood volume with adequate resuscitation is imperative. Isotonic crystalloid is the first replacement fluid of choice, but typed and cross-matched blood products are needed for the majority of patients with variceal hemorrhage. Evidence supports the use of colloids over crystalloid and packed red blood cells with the end points of optimal hemodynamics and oxygen transport (Shoemaker, 1987). Maintenance of hemoglobin values of approximately 8 g/dL are recommended; higher blood volumes are associated with increased portal pressures, higher rebleeding rates, and higher mortality rates. Other measures of the adequacy of resuscitation include systolic blood pressures of 90 to 100 mm Hg, central venous pressures of 9 to 16 mm Hg, and adequate urine output; pulmonary artery occlusion catheters may be a useful adjunct in some patients. When the adjusted prothrombin time is prolonged by more than 3 to 4 seconds, fresh frozen plasma is likewise recommended. Recombinant Factor VIIa has not been shown to benefit patients with cirrhosis with gastrointestinal (GI) hemorrhage over standard therapy (Bosch et al, 2008). For patients with significant bleeding or decreased consciousness, endotracheal intubation should be expedited.

Complications from variceal bleeding contribute to overall morbidity and mortality related to chronic liver disease. Preventing these complications can therefore have a significant impact on the short-term mortality rate associated with variceal bleeding. Antibiotic prophylaxis has been shown to decrease variceal rebleeding and bacterial infection (Bernard et al, 1999; Fernandez et al, 2006). Systematic reviews have shown decreased mortality rates with antibiotic prophylaxis in the setting of GI bleeding (Soares-Weiser et al, 2002). Consensus agreement supports norfloxacin use for 7 days (400 mg bid) in patients with two or more of the following: malnutrition, ascites, encephalopathy, or serum bilirubin level greater than 3 mg/dL. Ceftriaxone had better outcomes than norfloxacin when given intravenously in areas with known quinolone resistance according to randomized, controlled data (Fernandez et al, 2006). It may be that other antibiotics with similar spectra of activity would provide satisfactory substitutes in the event of problems with patient tolerance, local antibiotic availability, or susceptibility issues.

Controlling Acute Hemorrhage: Pharmacologic Agents

Coupling pharmacologic measures and endoscopy with the initiation of preventative measures provides the most sustainable results when attempting to control acute GI hemorrhage in patients with advanced liver disease. The specific drugs are widely available, generally safe, and can be initiated as soon as variceal hemorrhage is suspected. Drugs such as somatostatin or its analogues, octreotide and vapreotide, work by constricting arterial and thus venous splanchnic blood flow, thereby reducing portal hypertension acutely. In randomized controlled trials comparing these vasoactive agents with others, including vasopressin and terlipressin, no significant differences in bleeding control were reported, although vasopressin was associated with more adverse events (Banares et al, 2002; Villaneuva et al, 2006). Currently, an initial bolus dose of octreotide 50 µg IV followed by 50 µg/h is recommended. Duration usually extends from 72 hours to 5 days, and recurrent bleeding should be treated with an additional bolus dose. Only octreotide and vasopressin are currently available in the United States.

Controlling Acute Hemorrhage: Endoscopic Therapy

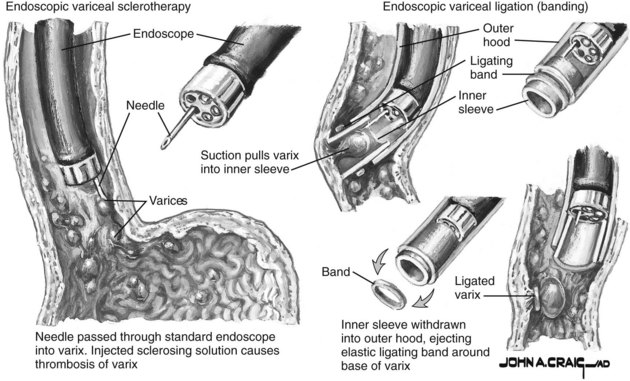

The two main endoscopic therapeutic choices are endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) and sclerotherapy. The strong preference remains for EVL, given its superior control of bleeding and decreases reported in rebleeding rates, mortality rates, and esophageal complications. Both techniques require a skilled endoscopist; however, when both groups were treated with somatostatin concomitantly, failure rates of EVL were estimated at 10% compared with 24% of sclerotherapy patients. Failure to control acute bleeding is also significantly more frequent in the sclerotherapy group (Villanueva et al, 2006).

After adequate sedation and diagnostic endoscopy, EVL should commence. The decision regarding whether to start with a standard 2.8-mm gastroscope versus a therapeutic endoscope is practitioner dependent given the potential for clot removal by irrigation. Once a variceal source has been identified, the endoscope should be removed and a multibanding kit should be applied with a standard gastroscope. Bands should be applied to any vessels actively spurting blood or displaying stigmata of recent hemorrhage, such as red wale marks, white nipples, and/or adherent blood clots. Other vessels should then be ligated, starting as close as possible to the esophagogastric junction. The varix is drawn into the ligator by applying suction, and a band is then applied as shown in Figure 75B.1.

FIGURE 75B.1 Variceal bleeding ligation techniques.

(Netter illustration from www.netterimages.com. Copyright Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved.)

Balloon Tamponade

The balloon tube should be inserted by a practitioner familiar with the technique (details presented below). The tube should be left in place for as short a time as needed for resuscitation, endoscopic treatment, or TIPS placement. Bleeding that continues after tube insertion warrants additional assessment regarding correct placement and potential for repeat endoscopy. In these cases, a bleeding lesion below the balloon in the distal stomach or duodenum that was missed at the first diagnostic endoscopy is usually the culprit (Terblanche et al, 1994).

Technique

Patients with a balloon tube in place are monitored carefully in an intensive care unit (ICU). When the balloon tube has been inserted and fixed and bleeding has been arrested, resuscitation is continued, clotting abnormalities are corrected, and the patient is made as fit as possible for the necessary subsequent management. The balloon tube should usually be removed within 24 hours (Blumgart & Belghiti, 2007).

Gastric Varices

Approximately 20% of patients with cirrhosis have gastric varices, either in isolation or associated with esophageal varices. Bleeding from gastric varices carries greater risk and is associated with increased mortality rates (Ryan et al, 2004). In these cases, endoscopic variceal obturation (EVO) with cyanoacrylate has been demonstrated as superior to endoscopic variceal ligation in controlling initial hemorrhage as well as controlling rebleeding (Lo et al, 2001; Tan et al, 2006). TIPS is also effective in controlling acute hemorrhage from gastric varices. Decreased recurrent bleeding has recently been demonstrated in patients undergoing TIPS versus EVO (Lo et al, 2007). In the United States, where N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate is not available and 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate has been used instead, adverse events have been noted. Its use requires specialized endoscopic training; in situations where this is not available, primary placement of TIPS is preferred (Garcia-Tsao & Lim, 2009).

Ectopic Varices

Ectopic varices are those in an atypical location (nonesophageal or nongastric). Bleeding from ectopic varices accounts for approximately 1% to 5% of variceal bleeding (Helmy et al, 2008). Most ectopic varices arise from global portal hypertension, but they may be related to regional thrombosis or prior surgery sites, where the healing process promotes venous connections between a high-pressure portal system and the lower pressure systemic circulation. Common sites include the duodenum, anorectal region, umbilicus, and ostomies. Patients typically bleed into the lumen of the GI tract, but peritoneal and retroperitoneal bleeding can occasionally occur. Given their relatively rare occurrence, treatment recommendations have been made on case reports, case series, and small reviews, not in randomized controlled trials.

Surgical treatment, including direct focal devascularization, is effective and usually performed in the presence of portal vein occlusion or advanced cirrhosis. Some of the direct approaches used are oversewing of varices via duodenotomy, duodenal dearterialization and stapling, circumferentially stapled anoplasty, and double-selective shunting. Nonselective portosystemic shunts (see Chapter 76D) are much more invasive and are therefore less commonly used (Helmy et al, 2008).

Portal Gastropathy and Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia

Recently, banding of antral mucosa has been described as a treatment for this condition. Up to 12 bands can be placed per session with about three sessions required to complete the treatment course. Banded mucosa is sloughed and replaced by mucosa without ectatic blood vessels. Wider experience with this modality will help determine the place of banding in this difficult to manage condition (Wells et al, 2008).

Recurrent Bleeding

GI hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis either recurs or cannot be controlled in approximately 10% to 20% of cases despite coordinated efforts with directed therapy. In these cases, shunt therapy is indicated. In Child-Turcotte-Pugh class A (compensated) cirrhotic patients, surgical shunts (see Chapters 76A through 76D) have proven efficacious. However, in most acute and later recurrences, TIPS is the preferred mechanism of portal decompression (see Chapter 76E). In addition to serving as a bridge to liver transplantation in patients not responding to pharmacologic and endoscopic therapy, TIPS is sometimes thought to be advantageous because of the lower portal pressures during transplantation. A TIPS functions as a nonselective shunt, and the development of encephalopathy or worsening of existing encephalopathy should be considered before implantation. Stenosis or occlusion may develop in up to 50% of patients within 1 year with bare metal stents; however, results appear to be improved when stents covered with polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) are used; both types of stents can be restored with angiographic interventions.

In the era of TIPS, an extensive gastric and lower esophageal devascularization together with transection of the lower esophagus is rarely required (see Chapter 75C). The extensive abdominothoracic Sugiura procedure popularized in Japan has been replaced by a transabdominal procedure in most institutions (Blumgart & Belghiti, 2007).

Abraldes JG, et al. Hepatic venous pressure gradient and prognosis in patients with acute variceal bleeding treated with pharmacologic and endoscopic therapy. J Hepatol. 2008;48(2):229-236.

Banares R, et al. Endoscopic treatment versus endoscopic plus pharmacologic treatment for acute variceal bleeding: a meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2002;35(3):609-615.

Bernard B, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of bacterial infections in cirrhotic patients with gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis. Hepatology. 1999;29(6):1655-1661.

Blumgart LH, Belghiti J. Surgery of the Liver, Biliary Tract, and Pancreas, 4th ed, vol. 2. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2007. p 1837

Bosch J, et al. Recombinant Factor VIIa for variceal bleeding in patients with advanced cirrhosis: a randomized, controlled trial. Hepatology. 2008;47(5):1604-1614.

Fernandez J, et al. Norfloxacin vs ceftriaxone in the prophylaxis of infections in patients with advanced cirrhosis and hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(4):1049-1056.

Garcia-Tsao G, Lim JK. Management and treatment of patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension: recommendations from the Department of Veterans Affairs Hepatitis C Resource Center Program and the National Hepatitis C Program. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(7):1802-1829.

Helmy A, Al Kahtani K, Al Fadda M. Updates in the pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of ectopic varices. Hepatol Int. 2008;2(3):322-334.

Lo GH, et al. A prospective, randomized trial of butyl cyanoacrylate injection versus band ligation in the management of bleeding gastric varices. Hepatology. 2001;33(5):1060-1064.

Lo GH, et al. A prospective, randomized controlled trial of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt versus cyanoacrylate injection in the prevention of gastric variceal rebleeding. Endoscopy. 2007;39(8):679-685.

Ryan BM, Stockbrugger RW, Ryan JM. A pathophysiologic, gastroenterologic, and radiologic approach to the management of gastric varices. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(4):1175-1189.

Shoemaker WC. Relation of oxygen transport patterns to the pathophysiology and therapy of shock states. Intensive Care Med. 1987;13(4):230-243.

Soares-Weiser K, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for cirrhotic patients with gastrointestinal bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2002. CD002907

Tan PC, et al. A randomized trial of endoscopic treatment of acute gastric variceal hemorrhage: N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate injection versus band ligation. Hepatology. 2006;43(4):690-697.

Terblanche J, et al. Long-term management of variceal bleeding: the place of varix injection and ligation. World J Surg. 1994;18(2):185-192.

Villanueva C, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing ligation and sclerotherapy as emergency endoscopic treatment added to somatostatin in acute variceal bleeding. J Hepatol. 2006;45(4):560-567.

Wells CD, et al. Treatment of gastric antral vascular ectasia (watermelon stomach) with endoscopic band ligation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68(2):231-236.