Chapter 58A Epidemiology of pancreatic cancer

Overview

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) accounts for 6% of all cancers in the United States. It is the fourth leading cause of cancer death in men, after lung, prostate, and colorectal cancer, and the fifth leading cause of cancer death in women, following lung, breast, colorectal, and ovarian cancer (Jemal et al, 2009). More than 42,000 incident cases of pancreas cancer are predicted annually, with about 35,240 deaths. Although mortality rates from pancreas cancer have improved slightly in the last decade, the diagnosis of PDA still confers an unfavorable prognosis.

Traditionally, PDA has been considered a predominantly male cancer; however, in 2009 the number of incident cases in women (21,420) exceeded the number of new cases in men (21,050) (Jemal et al, 2009). This suggests that the health consequences of increased smoking behavior by women over the last 3 decades are now becoming apparent. Pancreas cancer deaths remain higher in men (18,030) than in women (17,210), perhaps because of the presence of increased comorbidities or delayed diagnosis in men or greater genetic susceptibility to cancer, which limits treatment responsiveness in men (Jemal et al, 2009).

In the United States, the peak incidence of pancreas cancer occurs in the seventh and eighth decades of life (Horner et al, 2009). The U.S. population risk for pancreas cancer is 13.1 per 100,000 for men and 10.4 per 100,000 for women. The main risk for PDA occurs with advancing age. Between 2002 and 2006, the median age at diagnosis for cancer of the pancreas was 72 years, and the median age at death was 73 years according to Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data (Horner et al, 2009; SEER, 2010). Fifty-six percent of new PDA cases occur between the ages 65 and 84 years. The incidence of PDA remains highest for black Americans, with rates of 15.4 per 100,000 in men and 12.4 per 100,000 in women. The lowest risk of PDA is among Asian/Pacific Islander men and women (8.1 and 7.0 per 100,000, respectively). PDA is also a common second malignancy in both men and women who have had a prior smoking-related malignancy, such as lung or head and neck cancers (Neugut et al, 1995). The annual incidence rate worldwide for all histologic types of pancreas cancer is approximately 9 new cases per 100,000 persons (0.009), ranking it eleventh among all cancers.

In 2000, 217,000 new cases of pancreas cancer were reported globally, with 213,000 resultant deaths (Hariharan et al, 2008). The highest incidence of PDA in the world has been reported among Maoris in New Zealand, native Hawaiians, and black American populations; India and Nigeria have the lowest reported incidence (Boyle et al, 1989; Mack et al, 1985). In Europe during the same period, there were 60,139 incident cases with 64,801 deaths (Parkin et al, 2001). In Japan, PDA is the fifth leading cause of cancer death. Between 1950 and 1995, the worldwide incidence rates of PDA increased ninefold in men (1.4 to 12.5 per 100,000) and women (0.8 to 6.8 per 100,000), but rates have leveled off since 1985 (Lin et al, 1998). China reported 1619 deaths from pancreas cancer between 1991 and 2000, with rates higher in men and in urban areas compared with rural communities (Wang et al, 2003). No cases of PDA are reported in many African nations, reflecting the absence of an organized cancer registry system and an increased focus on more predominant causes of death in these nations. Incidence rates vary between 6 and 12 per 100,000 for the five Scandinavian countries, with Iceland having the lowest rates (Engholm et al, 2009).

Race And Ethnicity

African Americans

Combining all types of cancer, African Americans have the highest death rate (Ward et al, 2004) at 1.4 times higher than that of white males and 1.2 times higher than that of white females. In a 2004 study, Chang and colleagues (2004) used the California Cancer Registry of the Cancer Surveillance Section of the California Department of Health Services to determine the incidence of PDA between 1988 and 1998. African Americans had a higher age-adjusted incidence rate (8.8 per 100,000) for PDA when compared with all other races and ethnicities combined. African Americans were more likely to be seen with advanced disease and were least likely to receive surgical treatment, regardless of stage of disease (82.9% had no surgery compared with 77% of Asians, 67.8% of Hispanics, and 62.5% of non-Hispanic whites). Interestingly, serum cotinine levels, the primary metabolite of nicotine, are consistently higher in African Americans than in whites and Mexican Americans, even after adjustment for the number of cigarettes smoked per day, the number of smokers in the home, the number of hours of environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) exposure at work, the number of rooms in the home, and the region of the country where the subject lived (Caraballo et al, 1998). This suggests that genetic differences in cigarette product metabolism may influence rates of PDA.

Asians

Asian patients with PDA tend to have less aggressive tumors than do non-Asians (either black or white patients) and higher survival rates when assessed on a stage-adjusted basis (Clegg et al, 2008). To determine whether Asians develop a histologically different type of PDA than Western populations, Longnecker and colleagues (2000) conducted a population-based study using three SEER geographic areas: Hawaii, San Francisco, and Seattle. They compared PDA cases in Japanese, Chinese, Filipino, Hawaiian, black, and white patients. The study revealed that Japanese patients had the highest fraction of localized tumors with the lowest grade, and that Chinese, Filipino, and Japanese women had longer survival times than did whites, although survival time was significantly different for Japanese women only. Race-related genetic and environmental exposure factors may be involved in these survival discrepancies.

Ashkenazi Jews

Pancreatic cancer occurs in excess in Jews, particularly Jews of Ashkenazi heritage (Lynch et al, 1996). The age-standardized rates for PDA in Jews in Israel significantly exceed the rates for Israeli non-Jews (7.2 per 100,000 for all Jewish men and 5.7 per 100,000 for Jewish women vs. 4.0 per 100,000 for non-Jewish men and 2.9 per 100,000 for non-Jewish women). Approximately 5% to 10% of this discrepancy is attributed to the BRCA2 mutation, which is associated with breast, gastric, ovarian, and bile duct cancers.

Risk Factors For Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma

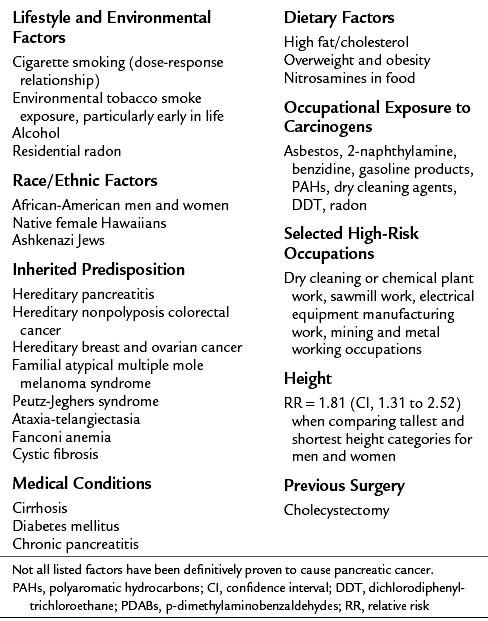

Our understanding of the risk factors for PDA continues to evolve. PDA is characterized by multiple germline and somatic genetic mutations (Hruban et al, 1998). This topic is covered extensively in Chapter 8A. It is estimated that less than 3% of pancreatic cancers are truly hereditary and due to inherited germline mutations and their respective syndromes (Wang et al, 2009). Other reported risk factors for PDA include cigarette, cigar, and pipe smoking; ETS exposure, also known as second-hand smoke or passive smoke exposure; exposure to occupational and environmental carcinogens; African American race; Ashkenazi Jewish heritage; high-fat, high-cholesterol diet; obesity; alcohol abuse; chronic pancreatitis; and long-standing diabetes (Table 58A.1; Gold et al, 1998; Everhardt et al, 1995; Silverman et al, 1994; Wynder, 1975).

Data from Ahlgren, 1996; Efthimiou et al, 2001; Ekbom et al, 1994; Garabrant et al, 1993; Gold et al, 1998; Hruban et al, 1998; Kogevinas et al, 2000; Lowenfels et al, 1997; Lynch et al, 1996; Michaud et al, 2001; Silverman et al, 1998; and Yeo et al, 2009.

Familial Pancreatic Cancer

Family history of pancreatic cancer is a strong risk factor in 5% to 10% of cases (Lowenfels et al, 2005). When a history of PDA exists in a close relative, a number of responsible genes have been identified (Wang et al, 2009). In the National Familial Pancreas Tumor Registry (NFPTR) at Johns Hopkins, prospective studies of family members of pancreas cancer kindreds found a twofold increased risk of pancreas cancer in the first-degree relatives of persons with sporadic pancreas cancer and a ninefold increased risk in first-degree relatives of those with familial pancreatic cancer (Klein et al, 2004; Wang et al, 2009). Germline mutations of BRCA2 are found in 6% to 19% of familial pancreatic cancer patients (Murphy et al, 2002). When a more stringent definition of familial pancreas cancer is used, a 57-fold increased risk of PDA was reported in kindreds with three or more family members affected with PDA (Tersmette et al, 2001). This corresponds to an incidence rate of 301 cases per 100,000 per year compared with the SEER age-adjusted rate for the entire U.S. population of 8.8 cases per 100,000 per year. A recent report identified a germline truncating mutation of the PALB2 gene in 3% of familial pancreas cancer patients (Jones et al, 2009; Blackford et al, 2009). Despite these many advances in the understanding of the mutations involved in the pathogenesis of PDA, no single “pancreas cancer gene” has been identified.

Six Genetic Syndromes Associated with Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma

Six genetic familial syndromes and their respective predisposing genes have been identified and linked to the development of PDA; these are described briefly below (see also Table 58A.2). Although individuals with these syndromes have an increased risk of developing PDA, collectively these syndromes account for less than 5% of the familial aggregation of PDA. The mean age of onset of familial PDA is similar to that of nonfamilial cases: 65.8 years versus 65.2 years (Hruban et al, 1998). Familial cases have also been noted to have a somewhat increased incidence of secondary primary cancers (23.8%) when compared with their nonfamilial counterparts (18.9%).

Table 58A.2 High-Risk Genetic Disorders Associated with Familial Pancreatic Cancer

| Genetic Syndrome | Gene/Chromosomal Mutation Region | Estimated Increased Risk of PDA |

|---|---|---|

| Hereditary pancreatitis | PRSS1 (7q35) | 50 to 80 times |

| Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch II variant) | hMSH2, hMSH1, hPMS2, hMSH3, hPMS1, hMSH6/GTBP | Undefined |

| Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer | BRCA2 (13q12-q13) | 3.5 to 10 times |

| FAMMM syndrome | p16 (9p21) | 20 to 34 times |

| Peutz-Jeghers syndrome | STK11/LKB1 (19p13) | 75 to 132 times |

| Ataxia-telangiectasia | ATM (11q22-23) | Rare |

FAMMM, Familial atypical multiple mole melanoma; PDA, pancreatic ductal carcinoma

Hereditary Pancreatitis

Children and adolescents with hereditary pancreatitis (HP) may develop severe pancreatitis at a young age, often in childhood or adolescence, with a resultant 50-fold to 80-fold increased risk of PDA developing over their lifetime. HP results from germline or new somatic mutations in the PRSS1 cationic trypsinogen gene (Lowenfels et al, 1997). Approximately 40% of those with HP will develop PDA when the additional risk factor of cigarette smoking is added. The risk of cancer seems to be limited to pancreatic cancers and not tumors in other organs.

Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer

Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) is an autosomal dominant inherited disease that predisposes affected persons to colorectal cancer and PDA (Hruban et al, 2002). It is usually caused by germline mutations in a number of DNA mismatch repair genes. Of the inherited syndromes associated with an increased risk of PDA, HNPCC is the least strongly linked to PDA.

Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer

Patients with germline BRCA2 mutations have up to a 10-fold increased risk (range, 3.5 to ×10) of PDA developing even in patients without a strong family history of breast cancer. Goggins and colleagues (1996) identified germline BRCA2 mutations in 7% of sporadic (nonfamilial) PDA patients screened, none of whom had a family history of breast cancer or PDA.

Familial Atypical Multiple Mole and Melanoma Syndrome

Familial atypical multiple mole and melanoma (FAMMM) syndrome is rare condition associated with p16 germline mutations, a tumor suppressor gene that may be mutated or may have its expression altered by posttranscriptional methylation. The syndrome predisposes affected individuals to melanomas, multiple nevi, atypical nevi, and PDA (Lynch et al, 1990). Those with FAMMM have a 20- to 34-fold increased risk of PDA over their lifetime.

Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is a rare autosomal dominant disease associated with alterations in the STK11 gene, in which affected individuals develop hamartomatous polyps of the gastrointestinal tract and lip freckles referred to as mucocutaneous melanocytic macules (Hruban et al, 2002). Individuals with this syndrome have a roughly 100-fold increased risk of developing PDA (Giardiello et al, 2000), and they also appear to have a tendency to form intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs).

Ataxia-Telangiectasia

Ataxia-telangiectasia is an autosomal recessive inherited disorder associated with ATM gene mutations, in which affected persons present with cerebellar ataxia, conjunctival telangiectasias, a hypofunctioning thymus gland, and oculomotor abnormalities. An association between ataxia-telangectasia and the subsequent development of PDA has been reported, but it is less well established than with the other five familial syndromes (Lynch et al, 1996).

Tobacco Exposure

Cigarette smoking is a contributing factor in approximately 20% to 25% of the cases of PDA and is the most consistently reported risk factor (Iodice et al, 2008; Jemal et al, 2009). Smoking has been associated with increased risk of PDA in at least 29 epidemiologic studies (Silverman et al, 1994), and smokers have a 70% increased risk of PDA compared with nonsmokers. Smoking habits in the 15 years preceding the diagnosis of PDA appear to be more relevant to increased risk, whereas former smokers who have quit for more than 13 years decrease their PDA risk to that of a lifetime nonsmoker (Howe et al, 1991).

Prospective and retrospective studies have found that the risk of PDA increases consistently with cigarette smoking but only inconsistently with cigar or pipe smoking (Wynder, 1975), suggesting perhaps that smoke must be deeply inhaled to exert its carcinogenic effects. A dose-response relationship between PDA and the number of cigarettes consumed has been documented in several investigations (Ahlgren, 1996; Howe et al, 1991). For current smokers who also have a family history of PDA, the relative risk of PDA has been reported to be as high as 8.23 (Schenk, 2001). Lowenfels and colleagues (1997) found that individuals with familial PDA tend to smoke more than those with sporadic PDA. These observations raise the possibility that smoking is interactive, perhaps multiplicatively, with genetic mutations known to be present in persons with familial PDA. Postmortem examinations of the pancreatic ducts of smokers have found widespread ductal hyperplasia, now called pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN), considered to be a premalignant lesion. Neugut and associates (1995) found a relationship between cigarette smoking and the development of PDA as a second malignancy in patients with a smoking-related first malignancy, such as lung, head and neck, or bladder cancer. This relationship is likely due to overlapping smoking-related genetic mutations among these different malignancies.

The socioeconomic status (SES) gap among smokers is widening in the United States and globally. Decreases in smoking prevalence in the U.S. population as a whole have not been realized in those from a lower SES background (Gilman et al, 2003). In a 2003 study of 657 adults aged 30 to 39 years that used parental occupation, adult educational attainment, and household income as indicators of SES, those of a lower SES were more likely to start smoking and to become regular smokers and were less likely to quit smoking than their higher SES counterparts.

The carcinogenic components of cigarette smoke are usually cleared from the bloodstream and excreted into bile; they reach the pancreas from the bile duct through biliary-pancreatic reflux, or they may be carried into the pancreatic parenchyma directly by the bloodstream. Cigarette smoke contains more than 60 known carcinogens, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), nitrosamines, benzo[a]pyrene, β-napthylamine, methylfluoranthenes, and arylamines (Hecht, 2003). These carcinogens may bind to DNA and form adducts, which increase the risk of somatic mutations and cancer if unrepaired. Nitrosamines are known to be organ specific, causing pancreatic carcinomas in hamsters that are histologically similar to the type found in humans (Wang et al, 2009). Little research has been conducted on the other carcinogens in cigarette smoke and their relationship to PDA. Another possible mechanism by which cigarette smoke leads to PDA is unrelated to the carcinogens in the smoke. Rather, higher cholesterol (lipid) levels are measured in smokers than in nonsmokers. The pathophysiologic mechanism of hypercholesterolemia may be partially due to nicotinic stimulation of circulating catecholamines, which increase serum cholesterol levels. Elevated lipid levels may be causative in the induction of PDA (Wang et al, 2009).

Mulder and colleagues (1999) developed multicountry computer-based models to estimate the impact of smoking cessation on the incidence of PDA in the European Union (EU). According to these models, the EU would reach a projected 600,000 new cases of PDA per year by 2020 if the present smoking levels were to continue. If all current smokers quit smoking, the predicted number of incident cases of PDA per year in the EU would be 175,000 by 2020. If 45% to 50% of smokers were able to successfully quit smoking, the reduction of new cases would still be a substantial 68,000 cases per year.

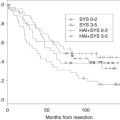

Environmental Tobacco Smoke

ETS is related to the development of PDA, with a possible dose-response relationship (Ahlgren, 1996; Villeneuve et al, 2004). A mildly elevated odds ratio (OR, 1.2.1; confidence interval [CI], 0.60 to 2.44) has been reported, suggesting a weak association between PDA and ETS exposure in nonsmokers who reported ETS exposure both as an adult and in childhood. The effect was more pronounced in smokers who reported ETS exposure. Recently published findings from a retrospective case-only analysis of familial and sporadic PDA indicate that nonsmokers with PDA who were exposed to ETS early in life (<21 years of age) were diagnosed with PDA at a significantly younger mean age (64.0 years) when compared with nonsmoker, non–ETS-exposed cases (66.5 years) (Yeo et al, 2009). Moreover, both cigarette smoking and ETS exposure in nonsmokers younger than 21 years is associated with a younger mean age of diagnosis in both familial, sporadic, and Ashkenazi Jewish cases of PDA.

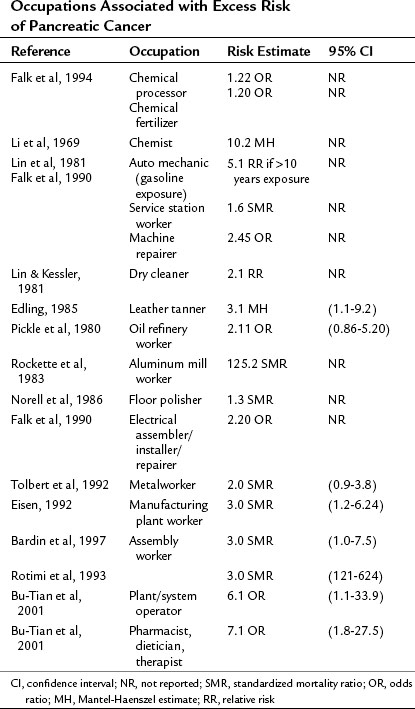

High-Risk Occupations

The evidence linking occupational exposures to PDA is inconsistent, reflecting the difficulty of quantifying workplace exposure to carcinogens and of differentiating these exposures from other risk factors. A number of epidemiologic investigations have suggested excess risk of pancreatic cancer in certain occupations. Definitively establishing certain occupations as high risk for the development of PDA is difficult because of the problems with self-reported exposures, lack of objective quantitative monitoring data, personal comorbidities, and the presence of other confounding and modifying risk factors. The available studies are summarized in Table 58A.3.

Occupational Exposures

Studies examining occupational exposures that increase a worker’s risk of developing PDA have been conducted both in the United States and in Europe, particularly in the Scandinavian countries. Occupational exposures linked to PDA are summarized in Table 58A.4. Overall the occupational etiologic fraction for PDA was estimated at 12% in a meta-analysis of 20 occupational studies conducted between 1969 and 1998 (Ojajarvi et al, 2000). A retrospective analysis of more than 22 occupational and environmental studies reported by people with PDA found that exposure to asbestos, pesticides and herbicides, residential radon, coal products, welding products, and radiation were the most commonly reported exposures (Yeo et al, 2009).

Table 58A.4 Occupational Exposures Linked to Pancreatic Cancer

| Chemical | Exposure Route | PDA Risk Estimates |

|---|---|---|

| Methylene chloride (chlorinated hydrocarbons) | Spray paintsPaint strippersAerosol propellantMetal degreasing agentPaint/paint thinnersVarnishSolvents | 1.61 OR1.40 OR1.6 risk ratio |

| Pesticides/herbicides DDT DDD Ethylan | Corn wet-millingFarmingFlight attendants | 1.4 OR4.8 RR4.3 RR5.0 RR |

| Asbestos | Industrial | 3.0 OR |

| Fertilizer | Farming | 1.2 OR |

| Cotton dust | Farming | 4.37 OR |

| Cement | Construction work (manufacturing of cement) | 1.28 OR |

| Lead | Various | 1.28 OR |

| Metalworking fluids | Machinist | 2.0 OR |

DDD, Dichlorodiphenyl-dichlorethane; OR, odds ratio; RR, relative risk

Data from references cited in Table 58A.3.

Calvert and colleagues (1989) conducted a review supported by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) of five cohort studies reporting an association between the use of metalworking fluids (MWFs) used in industrial machining and grinding operations and the development of all types of cancer, including PDA (Acquavella et al, 1993; Hoppin et al, 2000; Porta et al, 1999; Rotimi et al, 1993; Tolbert et al, 1992). More than 1 million workers are exposed to MWFs according to NIOSH estimates (Calvert et al, 1989). Substantial evidence was found for an increased risk of cancer at several sites, including the pancreas, larynx, rectum, skin, scrotum, and bladder. MWFs contain a number of compounds suspected to be cancer initiators or promoters including long-chain aliphatics, polyaromatic hydrocarbons, nitrosamines, sulfur-containing compounds, formaldehyde-releasing biocides, and heavy metals (Tolbert et al, 1992).

Diabetes Mellitus

Two theories regarding the relationship between type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) and PDA have been postulated; in one theory, DM is viewed as a predisposing risk factor for PDA; in the other theory, type 2 DM and its attendant altered glucose homeostasis are considered a consequence of PDA (Yalniz et al, 2005). The majority of PDA patients (80%) have either subclinical impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 DM. Many investigators regard DM as a clinical manifestation of PDA rather than a risk factor, a result of the alteration of islet cell function—specifically, the loss of β-cell mass from tumor growth—or a result of disruptions in acinar–islet cell interactions.

A meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies focused on DM and the risk of PDA found that the pooled relative risk (RR) of PDA in people diagnosed with DM 5 years or more prior to the PDA diagnosis was twice the risk (RR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.3 to 2.2) of those without DM (Everhardt et al, 1995). In a population-based case-control study of 484 PDA cases and 2099 controls in three geographic areas of the United States, those diagnosed with DM at least 10 years prior to the development of PDA had a 50% increased risk of PDA compared with the control group (Silverman et al, 1998). Insulin treatment did not appear to alter the risk of development of PDA (OR, 1.6 with insulin and 1.5 without).

During an 18-year follow-up study of 88,802 women in the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), 180 incident cases of PDA were reported (Michaud et al, 2001). A positive association was observed between fructose intake and impaired glucose metabolism and increased PDA risk. The risk was most apparent in women with an elevated body mass index (BMI) above 30 kg/m2 and low physical activity. A diet high in glycemic load (GL), the glucose response to each unit of carbohydrate-containing foods, may increase the risk of PDA in women with underlying insulin resistance as a result of obesity. Chronically elevated plasma glucose levels and increased PDA risk were also observed by Gapstur and colleagues (2000), further suggesting that impaired glucose tolerance, insulin resistance, and hyperinsulinemia may be involved in the etiology of PDA.

Chronic Pancreatitis

Chronic pancreatitis has been linked to the development of PDA. It is not clear whether chronic pancreatitis is a risk factor or if it represents an indolent presentation of PDA. The standardized incidence ratio of PDA in individuals with a diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis was 16.5 compared with the 1.76 expected number of cases (Lowenfels et al, 1993). Because PDA may mimic chronic pancreatitis, misdiagnosis is a possibility. A review of the records of patients with acute, chronic, or unspecified pancreatitis was conducted on all inpatient medical institutions in Sweden from 1965 to 1983. In 7956 patients with pancreatitis, 46 pancreas cancers were diagnosed compared with 21 expected cases—a standardized incidence ratio of 2.2 (CI, 1.6 to 2.9) (Ekbom et al, 1994). Although it seems reasonable to conclude that the cellular destruction and glandular dysfunction caused by pancreatitis may yield an environment favoring the initiation of tumor growth, it remains problematic that some premalignant lesions may be initially incorrectly diagnosed as chronic pancreatitis.

Cholecystectomy

A history of cholelithiasis and/or cholecystectomy may precede the diagnosis of PDA, yet cholecystectomy per se is not believed to promote its development. Individuals who underwent cholecystectomy in the year preceding the diagnosis of PDA had an exceedingly high risk of developing PDA (OR, 57.9) in one investigation (Everhardt et al, 1995). This finding is most likely explained by the misdiagnosis of gallbladder disease, either cholelithiasis or cholecystitis, in the setting of cryptic PDA, often prompting gallbladder removal with an undetected tumor being left in place. However, when data subset analyses were performed in patients with a history of cholecystectomy 20 years or more prior to the diagnosis of PDA, a 70% excess risk of PDA was still evident.

Hormonal Factors

In recent years, a link between female reproductive factors and PDA has been hypothesized. A case-control study of 52 postmenopausal women with PDA and 233 matched controls was conducted as a component of the Canadian Enhanced Cancer Surveillance Project (Kreiger et al, 2001). A questionnaire focused on reproductive history, cigarette smoking, physical activity, diet, occupation, residential history, and sociodemographic information was mailed to eligible patients diagnosed with PDA. Multiparity, defined as three or more children, and use of oral contraceptives were associated with a decreased risk of PDA (OR, 0.22 and 0.36, respectively). Late age at birth of first child significantly increased the risk of PDA (OR, 4.05; CI, 1.50 to 10.92 for ages 25 to 29 years; for women 30 or older, OR, 3.78; CI, 1.02 to 14.06). No relationships were found between age of menarche or menopause and PDA. The inverse relationship between parity and PDA suggests that PDA may be partially an estrogen-dependent transformation, or that estrogen may act in an inhibitory manner upon pancreatic carcinogenesis.

Lifestyle Factors and Height

Michaud and associates (2001) reported on the relationship between BMI, height, physical activity, and smoking and the risk of PDA in two large, prospective cohort studies: the Health Professional Follow-up Study (HPFS) and the NHS. Activity levels and body weight were ascertained prospectively. A higher risk of PDA was found among obese men and women, as was a direct association between above-average height and risk of PDA. An additional 2.54 centimeters of height above average increased the risk of PDA by 6% in the HPFS and by 10% in the NHS. The association between height and cancer risk in general has been identified in other studies (Giovannucci et al, 1995; Smith et al, 1998). Height may serve as a proxy for calorie intake or exposure to growth factors, such as insulin or insulinlike growth factor-1, in childhood.

Diet

It is estimated that 30% to 50% of pancreatic cancers may be attributable to dietary factors. Both butter consumption and saturated fat intake were positively associated with PDA (hazard ratio [HR], 1.40; CI, 0.87 to 2.25; and HR, 1.60; CI, 0.96 to 2.64, respectively) in the Finnish Cancer Registry (Stolzenberg-Solomon et al, 2005). Fat entering the duodenum stimulates cholecystokinin secretion, and it is possible that chronic hypercholecystokininemia may be associated with an increased susceptibility of the pancreas to carcinogens. Other possible explanations include that the increased intake of saturated fat may lead to insulin resistance and the development of DM, or foods with a high soluble fat content may be contaminated with carcinogenic organochloride compounds from the environment.

Processed meats have been linked to the development of PDA. In a prospective study of more than 200,000 people, 482 individuals developed PDA during 7 years of follow-up (Nöthlings et al, 2007). Those who had consumed the greatest amount of processed meats had a 67% increased risk of PDA. Diets laden with pork and red meat intake were associated with a 50% increase in PDA risk, but poultry, fish, dairy product, and egg consumption conferred no additional risk. Heterocyclic amines and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons that form during high-temperature cooking are known to be carcinogenic and may be responsible for the increased risk of PDA observed with processed and barbecued meats. These compounds have also been linked to the development of other cancers.

Several recent investigations have focused on the relationship between glycemic load and glycemic index. Consumption of fruit juices and soda has been evaluated in six studies to date with conflicting results (Michaud et al, 2002; Mueller et al, 2010; Nöthlings et al, 2007; Silvera et al, 2005; Stolzenberg-Solomon et al, 2005). Two studies found no relationship between PDA and glycemic load, carbohydrate intake, or sugar, sucrose, or fructose intake (Johnson et al, 2005; Silvera et al, 2005). Three studies reported mixed findings (Michaud et al, 2002; Nöthlings et al, 2007; Stolzenberg-Solomon et al, 2005). In the Multiethnic Cohort Study, BMI modified the effect of high sucrose intake and the occurrence of PDA, with elevated BMI increasing the risk and normal BMI decreasing the risk (Nöthlings et al, 2007). A positive association with PDA was also observed with high fructose intake, but no association was observed with consumption of soft drinks (diet or regular).

Mueller and colleagues (2010) conducted a retrospective analysis of the Singapore Chinese Health Study regarding soft drink and fruit consumption and the risk of PDA. Among 63,257 participants, 142 incident PDA cases were identified. However, only 56.4% of the PDA cases were histologically confirmed, 5% were reported from death certificate data, and 38.8% were identified by signs and symptoms possibly related to PDA but not proven. The finding of an elevated HR for PDA in those who drink two to three soft drinks per week is suspect in this setting and requires further evaluation.

Coffee and Alcohol Consumption

Cohort studies from the 1970s and 1980s indicating that heavy coffee and alcohol consumption led to an excess risk of PDA were often confounded by excessive smoking among the heavy coffee and alcohol drinkers (Michaud et al, 2001). Three subsequent investigations have attempted to clarify this issue while controlling for smoking (Ghadirian et al, 1991; Lagergren et al, 2002; Michaud et al, 2001). Ghadirian and colleagues (1991) conducted a case-control study of residents of greater Montreal, obtaining all information through questionnaires administered to either the patient or a proxy. The results indicated that those who consumed alcohol were, in general, at lower risk for PDA (OR, 0.65; CI, 0.30 to 1.44). This was true for beer, white wine, and hard liquor. The odds ratio for red wine drinkers was elevated at 1.57, but it did not achieve statistical significance. Likewise, coffee drinkers had a lower overall risk of developing PDA (OR, 0.55; CI, 0.19 to 1.62), regardless of whether they drank caffeinated or decaffeinated coffee. The increased risk when coffee was taken on an empty stomach or between breakfast and lunch (OR, 1.30 and 1.15, respectively) was not statistically significant.

Lagergren and colleagues (2002) hypothesized that because heavy alcohol intake often causes chronic pancreatitis, which may be a risk factor for PDA, the ideal group to examine would be those with a diagnosis of alcoholism, alcoholic chronic pancreatitis, and alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Using the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare, data were collected on 178,688 patients over a 30-year period. A total of 305 incident cases of PDA were identified in the group, representing a 40% excess risk in observed compared with expected cases. Alcoholics with chronic pancreatitis or cirrhosis had a twofold increased risk of PDA. A major limitation of the study was the lack of information on smoking. The authors estimated that the observed excess risk of PDA in the alcoholic group “may be almost totally attributable to the confounding effect of smoking” (Lagergren et al, 2002).

Michaud and colleagues (2001) examined data on coffee and alcohol consumption and other dietary factors obtained at baseline in two large, national cohort studies. The HPFS, initiated in 1986, includes 51,529 men aged 40 to 75 years who responded to a mailed questionnaire; the NHS began in 1976 and includes 121,700 registered nurses. Follow-up information was gathered via a mailed questionnaire from both groups on age, marital status, weight, height, medical history, medication use, smoking status, physical activity, and intake of coffee and alcohol. The results regarding coffee and alcohol are compelling: during 1,907,222 person-years of follow-up, 288 incident cases of PDA were diagnosed. Data were analyzed separately for each of the cohorts and then pooled to compute overall RR estimates. The results revealed that neither coffee consumption nor alcohol consumption conferred an excess risk of PDA; a pooled RR of 0.62 was reported (95% CI, 0.27 to 1.43) for more than 3 cups of coffee per day versus no coffee, and a pooled RR of 1.00 (95% CI, 0.57 to 1.76) for more than 30 g alcohol per day versus no alcohol were found.

Most recently, Brand and colleagues examined data on 29,239 histologically confirmed cases of pancreas cancer from 350 U.S. hospitals between the years 1993 and 2003 by cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption self-reported history (Brand et al, 2009). Current smokers were diagnosed with PDA at significantly younger ages (6.3 to 8.6 years) than nonsmoking counterparts. Among nonsmokers, age at diagnosis of PDA progressed linearly according to the amount of alcohol consumed, from 6 years younger for minimal drinkers to 8.7 years younger for self-described heavy alcohol consumers.

Acquavella J, et al. Occupational experience and mortality among a cohort of metal components manufacturing workers. Epidemiology. 1993;4:428-434.

Ahlgren J. Epidemiology and risk factors in pancreatic cancer. Semin Oncol. 1996;23(2):241-250.

Bardin J, et al. Mortality studies of machining fluid exposure in the automobile industry. V. A case-control study of pancreatic cancer. Am J Ind Med. 1997;32:240-247.

Blackford A, et al. Genetic mutations associated with cigarette smoking in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3681-3688.

Boyle P, et al. Epidemiology of pancreas cancer 1988. Int J Pancreatol. 1989;5:327-346.

Brand R, et al. Pancreatic cancer patients who smoke and drink are diagnosed at younger ages. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(9):1007-1012.

Bu-Tian J, et al. Occupational exposures to pesticides and pancreatic cancer. Am J Ind Med. 2001;39:92-99.

Calvert G, et al. Cancer risks among workers exposed to metalworking fluids: a systematic review. Am J Ind Med. 1989;33:282-292.

Caraballo R, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in serum cotinine levels of cigarette smokers. JAMA. 1998;280(2):135-139.

Chang K, et al. Risk of pancreatic cancer. Cancer. 2004;103(2):349-357.

Clegg L, et al. Chapter 31: Race and Ethnicity. National Cancer Institute, SEER Survival Monograph; 2008. pp 263-276. Available at http://seer.cancer.gov/publications/survival/surv_race_ethnicity.pdf

Edling C, et al. Cancer mortality among leather tanners. Br J Ind Med. 1985;43:494-496.

Efthimiou E, et al. Inherited predisposition to pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2001;48:143-147.

Ekbom A, et al. Pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer: a population-based study. J Ntl Cancer Inst. 1994;86(8):625-627.

Eisen E, et al. Mortality studies of machining fluid exposure in the automobile industry I: a standardized mortality ratio analysis. Am J Ind Med. 1992;22:809-824.

Engholm G, et al. NORDCAN: Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Prevalence and Prediction in the Nordic Countries, Version 3.5. Association of the Nordic Cancer Registries, Danish Cancer Society. www.ancr.nu, 2009. Accessed 28 March 2010

Everhardt J, et al. Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for pancreatic cancer. JAMA. 1995;273:1605-1608.

Falk R, et al. Occupation and pancreatic cancer risk in Louisiana. Am J Ind Med. 1994;18:565-576.

Gapstur S, et al. Abnormal glucose metabolism and pancreatic cancer mortality. JAMA. 2000;283(12):1512-1523.

Garabrant D, et al. DDT and related compounds and risk of pancreatic cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;84(10):764-771.

Ghadirian P, et al. Tobacco, alcohol and coffee and cancer of the pancreas. Cancer. 1991;67:2664-2670.

Giardiello F, et al. Very high risk of cancer in familial Peutz–Jeghers syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2000;119(6):1447-1453.

Gilman S, et al. Socioeconomic status over the life course and stages of cigarette use: initiation, regular use, and cessation. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:802-808.

Giovannucci E, et al. Physical activity, obesity, and risk for colon cancer and adenoma in men. Ann Int Med. 1995;122:327-334.

Goggins M, et al. Germline BRCA2 gene mutations in patients with apparently sporadic pancreatic carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5360-5364.

Gold E, et al. Epidemiology of and risk factors for pancreatic cancer. Surg Oncol Clin North Am. 1998;7(1):67-91.

Hariharan D, et al. Analysis of mortality rates for pancreatic cancer across the world. HBP. 2008;10(1):58-62.

Hecht S. Tobacco carcinogens, their biomarkers and tobacco-induced cancer. Cancer. 2003;3(10):733-744.

Hoppin J, et al. Pancreatic cancer and serum organochlorine levels. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9(2):199-205.

Horner MJ, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2006. Bethesda, Md.: National Cancer Institute; 2009. Based on November 2008 SEER data submission. seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2006

Howe G, et al. Cigarette smoking and cancer of the pancreas: evidence from a population-based case-control study in Toronto Canada. Int J Cancer. 1991;47:323-328.

Hruban R, et al. Genetics of pancreatic cancer. Surg Onc Clinics N Amer. 1998;7(1):1-23.

Hruban R, et al. Pancreatic cancer. In: Vogelstein, B, Kinzler, K. The Genetic Basis of Human Cancer. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2002:659-669.

Iodice S, et al. Tobacco and the risk of pancreatic cancer: a review and meta-analysis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2008;393:535-545.

Jemal A, et al. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59(4):225-249.

Johnson KJ, et al. No association between dietary glycemic index or load and pancreatic cancer incidence in premenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(6):1574-1575.

Jones S, et al. Exomic sequencing identifies PALB2 as a pancreatic susceptibility gene. Science. 2009;324:2548-2552.

Klein AP, et al. Prospective risk of pancreatic cancer in familial pancreatic cancer kindreds. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2634-2638.

Kogevinas M, et al. Occupational exposures and pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2000;57(5):316-324.

Kreiger N, et al. Hormonal factors and pancreatic cancer in women. Ann Epidemiol. 2001;11(8):563-567.

Lagergren W, et al. Alcohol abuse and the risk of pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2002;51:236-239.

Li F, et al. Cancer mortality among chemists. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1969;43:1159-1164.

Lin R, et al. A multi-factorial model for pancreatic cancer in man: epidemiologic evidence. JAMA. 1981;45:147-152.

Lin Y, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of pancreas cancer in Japan. J Epidemiol. 1998;8(1):52-59.

Longnecker D, et al. Racial differences in pancreatic cancer: comparison of survival and histologic types of pancreatic carcinoma in Asians, blacks, and whites in the United States. Pancreas. 2000;21:338-343.

Lowenfels A, et al. Pancreatitis and the risk of pancreatic cancer: International Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;20(238):1433-1437.

Lowenfels A, et al. International Hereditary Pancreatitis Study Group: hereditary pancreatitis and the risk of pancreatic cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89(6):442-446.

Lowenfels AB, et al. Risk factors for pancreatic cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2005;95:649-656.

Lynch H, et al. Familial pancreatic cancer: clinicopathologic study of 18 nuclear families. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:54-60.

Lynch H, et al. Familial pancreatic cancer: a review. Semin Oncol. 1996;23(2):251-275.

Mack TM, et al. Pancreas cancer is unrelated to the workplace in Los Angeles. Am J Ind Med. 1985;7:253-266.

Michaud D, et al. Physical activity, obesity, height, and the risk of pancreatic cancer. JAMA. 2001;286(8):921-929.

Michaud D, et al. Dietary sugar, glycemic load and pancreatic cancer in a prospective study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;17:1293-1300.

Mueller N, et al. Soft drink and juice consumption and risk of pancreatic cancer: the Singapore Chinese Health Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(2):447-455.

Mulder I, et al. The impact of smoking on future pancreatic cancer: a computer simulation. Ann Oncol. 1999;10(S4):S74-S78.

Murphy K, et al. Evaluation of candidate genes MAP2K4, MADH4, ACVR1B and BRCA2 in familial pancreatic cancer: deleterious BRCA2 mutations in 17. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3789-3793.

Neugut A, et al. Pancreatic cancer as a second primary malignancy: a population-based study. Cancer. 1995;76:589-592.

Norell S, et al. Occupational factors and pancreatic cancer. Br J Med. 1986;43:775-778.

Nöthlings U, et al. Dietary glycemic load, added sugars, and carbohydrates as risk factors for pancreatic cancer: the Multiethnic Cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:1495-1501.

Ojajarvi I, et al. Occupational exposures and pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2000;57(5):316-324.

Parkin DM, et al. Cancer burden in the year 2000: the global picture. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(Suppl 8):S4-S66.

Pickle L, et al. Pancreatic cancer mortality in Louisiana. Am J Public Health. 1980;70(3):256-259.

Porta M, et al. Serum concentrations of organochlorine compounds and K-ras mutations in exocrine pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 1999;354:2125-2129.

Rockette H, et al. Mortality of aluminum reduction plant workers: pot room and carbon department. J Occup Med. 1983;25:549-557.

Rotimi C, et al. Retrospective follow-up study of foundry and engine plant workers. Am J Ind Med. 1993;24:485-498.

Schenk M. Familial risk of pancreatic cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(8):640-644.

Silvera S, et al. Glycemic index, glycemic load and pancreatic cancer risk (Canada). Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16:431-436.

Silverman D, et al. Cigarette smoking and pancreas cancer: a case-control study based on direct interviews. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86(20):1510-1516.

Silverman D, et al. Diabetes mellitus, other medical conditions and familial history of cancer as risk factors for pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 1998;80(11):1830-1837.

Smith G, et al. Height and mortality from cancer among men: prospective study. Br Med J. 1998;317:1351-1352.

Stolzenberg-Solomon R, et al. Insulin, glucose, insulin resistance, and pancreatic cancer in male smokers. JAMA. 2005;294:2872-2878.

Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Stat Fact Sheets. Pancreas. Available at seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/pancreas.html

Tersmette A, et al. Increased risk of incident pancreatic cancer among first-degree relatives of patients with familial pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:738-744.

Tolbert P, et al. Mortality studies of machining-fluid exposure in the automobile industry II: Risks associated with specific fluid types. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1992;18:351-360.

Villeneuve P, et al. Environmental tobacco smoke and the risk of pancreatic cancer: findings from a Canadian population-based case-control study. Can J Public Health. 2004;95(1):32-37.

Wang U, et al. Pancreatic cancer mortality in China (1991-2000). World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9(8):1819-1823.

Wang L, et al. Elevated cancer mortality in the relatives of patients with pancreatic cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Preven. 2009;18(11):2829-2834.

Ward E, et al. Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:78-93.

Wynder E. An epidemiological evaluation of the causes of cancer of the pancreas. Cancer Res. 1975;35:2228-2233.

Yalniz M, et al. Diabetes mellitus: a risk factor for pancreatic cancer? Arch Surg. 2005;390:66-72.

Yeo TP, et al. Assessment of gene-environment interaction in cases of familial pancreatic cancer compared to cases of sporadic pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13(8):1487-1494.