Chapter 87 Endogenous Endophthalmitis

Bacterial and Fungal

Epidemiology and risk factors

Endogenous endophthalmitis remains an uncommon but serious cause of intraocular inflammation.1 The incidence may be increasing, due to several factors. An increasing number of immunocompromised patients are receiving antineoplastic agents, immunomodulating agents, and newer broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents, all of which may reduce normal flora.2,3 Low-birthweight premature infants and patients with a history of intravenous substance abuse are at increased risk for endogenous endophthalmitis.4 Other reported risk factors include long-term intravenous line placement, peripheral hyperalimentation, systemic corticosteroids, abdominal surgery, hemodialysis, HIV infection, systemic malignancy, diabetes mellitus, pregnancy or postpartum state,5 massive systemic trauma, alcoholism, hepatic insufficiency, and genitourinary manipulation.6

One recent series of 64 cases over 10 years reported a culture positivity rate of 64%. Of culture-positive cases, fungi (predominantly Candida spp.) were isolated in 66%, Gram-negative bacteria in 19%, and Gram-positive bacteria in 15%. Fungal cases were associated with better visual outcomes.7

Clinical assessment of the patient

Infectious endophthalmitis may be categorized by the cause of the infection and by the characteristic timing of clinical signs and symptoms. One proposed categorization scheme is presented in Box 87.1.8 In general, endogenous endophthalmitis is suspected in a patient without risk factors for exogenous endophthalmitis, such as prior surgery, trauma, or keratitis. Patients with endogenous endophthalmitis may present with varying degrees of pain, inflammation, and visual loss. In the anterior chamber, cell and flare, fibrin, posterior synechiae, and hypopyon may occur. In the posterior segment, findings may include vitreous opacification and chorioretinitis, including hemorrhage, cotton-wool spots, retinal opacification, and vasculitis. An insidious onset, focal vitreous opacities, and chorioretinal infiltrates suggest fungal etiology. Relatively more rapid progression and more severe intraocular inflammation suggest bacterial etiology.

Box 87.1

Classification of endophthalmitis and common causative organisms

Acute-onset postoperative endophthalmitis

Chronic (delayed-onset) postoperative endophthalmitis

Filtering bleb-associated endophthalmitis

Post-traumatic endophthalmitis

(Adapted from Schwartz SG, Flynn HW Jr, Scott IU. Endophthalmitis: classification and current management. Expert Rev Ophthalmol 2007;2:385–96.)

Endogenous endophthalmitis may present as a relatively mild and nonspecific anterior uveitis.9 Early in the clinical course, the clinical features may be subtle, making the diagnosis difficult. The rate of initial misdiagnosis has been reported as high as 63% in one large series.10 A differential diagnosis of endogenous endophthalmitis is presented in Box 87.2.

Box 87.2

Differential diagnosis of endogenous endophthalmitis

Cases may be classified according to several criteria. One published classification scheme for endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis used zones of anatomic involvement (Box 87.3).11 Another scheme, designed for endogenous fungal endophthalmitis, also used anatomic criteria (Box 87.4); in this series, the stage at initial diagnosis was statistically correlated to the final visual acuity.12

Box 87. 3

Anatomic classification of endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis

Focal: One or a few discrete foci in the iris, ciliary body, retina, or choroid

Anterior diffuse: Severe generalized signs of inflammation in the anterior segment

Posterior diffuse: Intense inflammatory reaction in vitreous, obscuring the fundus

Panophthalmitis: Severe involvement of anterior segment, posterior segment, and orbital structures

(Adapted from Greenwald MJ, Wohl LG, Sell CH. Metastatic bacterial endophthalmitis: a contemporary reappraisal. Surv Ophthalmol 1986;31:81–101.)

Box 87.4

Classification of endogenous fungal endophthalmitis

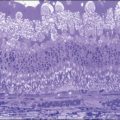

Stage I: Chorioretinal changes without extension into the vitreous cavity

Stage II: Fungal mass penetrating through the inner limiting membrane and budding into the vitreous cavity

(Adapted from Takebayashi H, Mizota A, Tanaka M. Relation between stage of endogenous fungal endophthalmitis and prognosis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2006;244:816–20.)

Medical evaluation of the patient

In contrast to patients with postoperative or post-traumatic endophthalmitis, nearly all patients with endogenous endophthalmitis have an identifiable systemic infection and require at least some degree of systemic evaluation. Generally, the medical evaluation is performed in consultation with an infectious disease specialist or other medical specialist. A high index of suspicion should be maintained, because both the ophthalmic and systemic symptoms are quite variable. In one series, 43% of patients with endogenous endophthalmitis had no nonocular symptoms.13 Endogenous endophthalmitis may present prior to the onset of systemic symptoms,14 or may occur in patients later found to have no other systemic infection.15 In one series, the rate of negative systemic workup was over 40%.16 In a patient not known to have systemic infection, intraocular cultures (aqueous, vitreous, or both) may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis. Intraocular cultures are also important in patients who progress despite treatment with empiric antimicrobial therapy.

Obtaining cultures from multiple sites may be necessary to make a specific diagnosis. In one series of patients with endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis, the rate of diagnostic cultures was 74% for vitreous, 72% for blood, and 96% overall.17 The rates of positive cultures are lower in patients with endogenous fungal endophthalmitis. Rates of positive cultures have been reported in the range of 44–70%,18 and as low as 18% in one prior series.19

Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis

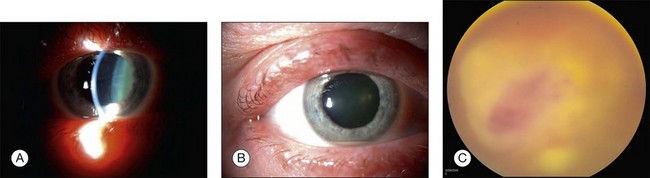

Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis is reported to comprise between 2% and 8% of all cases of infectious endophthalmitis (Fig. 87.1).20 Many bacteria have been reported to cause endogenous endophthalmitis. Gram-positive agents associated with bacterial endogenous endophthalmitis include Staphylococcus areus,21 group B Streptococcus,22 Streptococcus pneumoniae,23 Streptococcus bovis,24 Propionibacterium acnes,25 Listeria monocytogenes,26 Bacillus spp.,27 Nocardia spp.,28 and others. Gram-negative agents associated with bacterial endogenous endophthalmitis include Klebsiella pneumoniae,29 Pseudomonas aeruginosa,30 Escherichia coli,31 Enterococcus faecalis,32 Neisseria meningitidis,33 Proteus spp.,34 and others.

Endogenous fungal endophthalmitis

Over 50 000 species of fungi have been reported, yet fewer than 200 of these are associated with clinical disease in humans and even fewer have been reported to cause endogenous endophthalmitis (Box 87.5). Fungi may be differentiated using several criteria, but are commonly divided between unicellular yeasts and multicellular molds. Molds contain tubular structures (hyphae). Some fungi may grow with both yeast-like and mold-like morphology in tissues or culture. Fungi may also be classified by pigmentation (moniliaceous versus dermatiaceous), virulence (pathogenic versus opportunistic), or clinical presentation (cutaneous, subcutaneous, or systemic).

Box 87.5

Fungal isolates

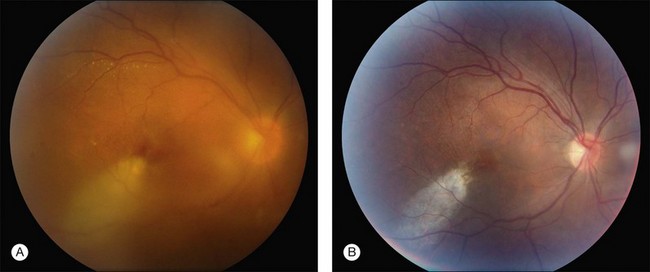

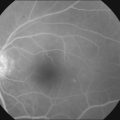

Candida albicans is the most common yeast isolate and the most common overall fungal isolate in patients with endogenous fungal endophthalmitis.35,36 C. albicans may be found as a commensal organism in the gastrointestinal tract and mucous membranes of healthy individuals.37Although the organism is of low virulence to healthy individuals, candidemia is associated with relatively high rates of morbidity and mortality.38 In one series, the mortality rate among patients with candidemia and endogenous Candida endophthalmitis was reported as 77%.39 Candida endophthalmitis is strongly associated with intravenous drug abuse.40 Other Candida species reported to cause endophthalmitis include C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, C. glabrata, C. guilliermondii, and C. krusei. Among patients with diagnosed candidemia, reported rates of endogenous endophthalmitis range from less than 3%41 to 44%.42 The prevalence of Candida endophthalmitis may be decreasing, as systemic antifungals are now more commonly prescribed for patients with positive blood cultures.43 The most characteristic clinical sign of Candida endophthlamitis is one or more creamy white, well-circumscribed chorioretinal lesion, less than 1 mm in diameter, most commonly in the posterior pole, with an overlying haze of vitreous inflammatory cells (Figs 87.2, 87.3). Yellow or fluffy-white vitreous opacities, sometimes connected by strands of inflammatory material (“string of pearls” configuration), may be noted. Recently, a subretinal abscess was reported in a patient with endogenous C. albicans endopthalmitis.44 The initial misdiagnosis rate may be high; one series reported this rate to approach 50%.45

Aspergillus is the most common mold isolate and the second most common overall fungal isolate in patients with endogenous fungal endophthalmitis.46 Reported risk factors include chronic pulmonary disease, liver transplantation,47 and treatment with systemic corticosteroids, but rare cases are reported in apparently immunocompetent individuals.48 Endogenous Aspergillus endophthalmitis is associated with a characteristic central macular chorioretinal inflammatory lesion.49 A gravitational layering (pseudohypopyon) of inflammatory exudates in either the preretinal (subhyaloid) or subretinal space may be noted with the macular lesion. Additionally, Aspergillus endophthalmitis may be associated with retinal vascular occlusion, choroidal vascular occlusion, and exudative retinal detachment.50 For these reasons, Aspergillus endophthalmitis generally has a poorer prognosis than Candida endophthalmitis. A case report documented a poor visual outcome, and eventual mortality, in a patient with acute myelogenous leukemia and bilateral endogenous Aspergillus fumigatus endophthalmitis despite prophylaxis with oral fluconazole. The intial ophthalmologic presentation was notable for diffuse hemorrhagic retinal necrosis, and the initial diagnosis was cytomegalovirus retinitis.51

Cryptococcus neoformans is associated with meningitis and visual loss through a variety of mechanisms, including cryptococcomas in the visual pathway, optic neuritis, and elevated intracranial pressure.52 C. neoformans may cause endophthalmitis, which is typically characterized by nonspecific intraocular inflammation, making initial misdiagnosis relatively common. The most common presentation is a multifocal chorioretinitis.53 Successful outcomes have been reported with a combination of systemic amphotericin B and fluconazole with intravitreal amphotericin B.54

Coccidioides immitis endophthalmitis is associated with chronic pulmonary or disseminated coccidioidomycosis.55 Endogenous endophthalmitis is infrequently reported.56 Asymptomatic patients with systemic coccidioidomycosis may have inactive chorioretinal scars, suggesting prior intraocular involvement.57 Alternatively, a case of ocular coccidiomycosis has been reported 22 years following treatment of systemic disease.58

Rare causes of endogenous fungal endophthalmitis include Histoplasma capsulatum,59 Sporothrix schenckii,60 and others.

Treatment strategies

Although successful treatment of chorioretinitis in a patient with systemic candidiasis has been reported after simply removing an infected catheter,61 most patients with endogenous endophthamitis require treatment with systemic antimicrobial agents. The choroid and retina are highly vascular structures, which suggests that systemic pharmacotherapy may be sufficient to treat infections confined to these structures, while severe intravitreal involvement may require intravitreal agents.62 In patients not responding to systemic therapy, intravitreal therapy should be considered. There is no current consensus regarding the precise role of surgical techniques, such as pars plana vitrectomy (PPV). The Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study (EVS) did not enroll patients with endogenous endophthalmitis and therefore its results are not directly applicable to these patients.63

Systemic pharmacotherapies

Systemic antimicrobials are associated with variable intravitreal penetration. For example, in a prospective study, intravenous teicoplanin was reported to have poor intravitreal penetration.64A more recent series of patients with postoperative endophthalmitis reported that systemic meropenem and linezolid offered no additional benefits.65

Alternatively, both systemic gatifloxacin66 and moxifloxacin67 have been reported to reach potentially therapeutic intraocular drug levels in the noninflamed eye, but their specific benefit in the treatment of endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis remains unproven. Systemic gatifloxacin is no longer commercially available, due to an associated dysglycemia in some patients.68 Additionally, systemic fluoroquinolones are associated with other serious adverse events, including tendinopathy, especially in the elderly and in patients taking systemic corticosteroids.69

A case report demonstrated that after a single dose of intravenous daptomycin, intravitreal concentrations of daptomycin were approximately 28% of the serum concentration, suggesting a potential role for this drug in the treatement of endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis.70

Systemic antibiotics may not prevent the onset of endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis. One case report documented that Pseudomonas aeruginosa endophthalmitis involved the second eye despite initation of intravenous ceftazidime.71

Commonly used systemic antifungals are reviewed in Box 87.6.

Amphotericin B has been widely used in the treatment of various fungal infections. An alternative liposomal formulation is also available,72 but experience with this formulation in the treatment of endogenous fungal endophthalmitis is limited at this time.73,74 Amphotericin B is administered intravenously, and is generally effective in the treatment of infections due to Candida,75 Aspergillus,76 Blastomyces,77 Coccidioides,78 and other fungi. The use of amphotericin B is limited by multiple toxic effects, including renal failure, chills, fever, vomiting, nausea, diarrhea, dyspnea, malaise, anemia, arrythmia, hypokalemia, and hearing loss.79 The intravitreal penetration of systemic amphotericin B is relatively poor, and although successful treatment of Candida endophthalmitis has been reported using systemic amphotericin B alone,80 this approach has a high rate of treatment failure.81 Either a systemic agent with better intraocular penetration, or combined systemic and intravitreal treatment, is generally selected.

Azoles collectively represent an alternative antifungal drug class. The imidazoles (miconazole and ketoconazole) were used historically, but largely have been replaced by the newer triazoles (fluconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, and posiconazole), although a case report documented a good outcome in endogenous Aspergillus terreus endophthalmitis using intravitreal amphotericin B, oral ketoconazole, and topical natamycin.82

Fluconazole has excellent gastrointestinal absorption and may be used orally or intravenously.83 Intraocular penetration from the systemic circulation is generally excellent.84 A case report documented good outcomes in a patient with bilateral endogenous C. albicans endophthalmitis using intravenous fluconazole and pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) in one eye only.85 Fluconazole (with or without PPV) has also been reported to successfully treat endophthalmitis caused by C. tropicalis,86 Coccidioides immitis,87 and Cryptococcus neoformans.88 Fluconazole is generally well tolerated, with gastrointestinal disturbance as the major reported toxicity.89 Oral fluconazole may be an appropriate antifungal choice in patients with chorioretinitis outside the posterior pole,90 in patients who have been initially treated with intravenous amphotericin B,91 and in patients at risk for toxicity.

Itraconazole also may be prescribed orally, but is used infrequently in the treatment of endogenous endophthalmitis.92 It has relatively more effectiveness against Aspergillus than the other azoles,93 but intraocular penetration is relatively poor.

Voriconazole is a synthetic second-generation azole derived from fluconazole. It may be used orally or intravenously. Voriconazole is generally effective against most Candida species (including those resistant to fluconazole, such as C. krusei and C. glabrata),94 as well as Aspergillus and Cryptococcus.95 Voriconazole has excellent intravitreal penetration from the systemic circulation.96 Oral voriconazole alone has been reported to successfully manage a patient with presumed endogenous Candida endophthalmitis.97

Posaconazole is a newer azole with efficacy against Candida, Aspergillus, and Zygomycetes.98 Relatively little is known about its intraocular penetration. Successful treatment of refractory Fusarium deep keratitis or endophthalmitis has been reported with oral (or oral plus topical) posaconazole.99,100

Commonly used echinochandins include caspofungin, micafungin, and anidulafungin. These are newer agents and, compared with amphotericin B and the azoles, relatively little has been reported about their use in endogenous endophthalmitis. Caspofungin may be effective against C. albicans resistant to azoles.101 One case report documented successful treatment of C. glabrata endophthalmitis using only systemic caspofungin.102 A second report documented treatment of A. fumigatus endophthalmitis resistant to intravitreal amphotericin and systemic voriconazole with systemic caspofungin.103

Intravitreal pharmacotherapies

The Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study (EVS) did not enroll patients with endogenous endophthalmitis and therefore its results are not applicable to these patients.63 However, many of the principles of the EVS apply to patients with endogenous endophthalmitis. The EVS used intravitreal vancomycin and amikacin, which achieved broad-spectrum coverage of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative organisms. In a patient with bacteremia due to a known organism, targeted pharmacotherapy may be considered in patients with suspected ocular involvement. To reduce the risk of aminoglycoside toxicity, ceftazidime or ceftriaxone may be considered as an alternative to amikacin. Ceftazidime may precipitate when mixed with vancomycin, but this does not appear to affect its clinical efficacy.104 Injecting antibiotics through separate syringes is generally recommended.

Intravitreal antifungals are listed in Box 87.7. Animal studies have suggested that intravitreal amphotericin B, 5–10 µg, is generally nontoxic.105 A case series of patients inadvertently treated with very high doses reported severe noninfectious panophthalmitis, but ultimately good visual outcomes, following treatment with doses as high as 500 µg.106 Intravitreal amphotericin B alone, without systemic therapy, has been reported to successfully treat endogenous Candida endopthalmitis.107 A case report documented good outcomes using PPV, intravitreal liposomal amphotericin B, and systemic fluconazole in a patient with bilateral endogenous C. albicans endophthalmitis.108

Intravitreal fluconazole has been tested in animal models,109,110 but does not appear to be any more effective than intravitreal amphotericin B and is thus rarely used clinically.111 Intravitreal ketoconazole has been reported safe in a rabbit model,112 but its use has not been reported in humans.

Based on animal models, intravitreal voriconazole appears to be nontoxic up to doses of 100 µg, and may be less toxic to the retina than intravitreal amphotericin B.113 Intravitreal voriconazole, combined with PPV, has been reported to successfully treat a patient with endogenous A. terreus endophthalmitis resistant to PPV with repeated injections of intravitreal amphotericin B and systemic voriconazole.114

Intravitreal corticosteroids (e.g., dexamethasone 400 µg) may be a helpful adjunct in some patients with bacterial or fungal endophthalmitis, by reducing inflammation.115 Generally, corticosteroids should be withheld until proper antimicrobials have been initiated, especially in patients with suspected fungal disease.

Surgical treatments

Although there is no general agreement on exactly which patients will benefit from PPV,116 surgical treatments are typically reserved for patients with established vitreous involvement.117 PPV offers the advantages of removing infectious organisms from the vitreous cavity and providing ample material for cultures. Disadvantages of PPV include surgical risks, such as retinal detachment, choroidal detachment, or sclerotomy site leakage. One large series reported improved outcomes in patients treated with PPV.118 In patients with endogenous fungal endophthalmitis treated with PPV and systemic antifungals, adjunctive intravitreal antifungals were not used in one series of Candida cases.119 In phakic patients with an uninvolved crystalline lens, lensectomy is not required at the time of vitreous surgery.120

Vitreous needle tap may be useful in hospitalized patients who are poor surgical candidates or in facilities where access to PPV instrumentation and support staff is limited (Fig. 87.4).Patients who fail to respond to tap and inject should be considered for PPV during subsequent follow-up.

Suggested management

In patients with clinically suspected endogenous endophthalmitis, the history, physical findings, and blood cultures may be useful to determine an etiology. Because of the relative infrequency of these cases (especially bacterial cases), there are no generally established treatment guidelines.121

1 Smith SR, Kroll AJ, Lou PL, et al. Endogenous bacterial and fungal endophthalmitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2007;47:173–183.

2 Essman TF, Flynn HW, Jr., Smiddy WE, et al. Treatment outcomes in a 10-year study of endogenous fungal endophthalmitis. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 1997;28:185–194.

3 Chakrabarti A, Shivaprakash MR, Singh R, et al. Fungal endophthalmitis: fourteen years’ experience from a center in India. Retina. 2008;28:1400–1407.

4 Schiedler V, Scott IU, Flynn HW, Jr., et al. Culture-proven endogenous endophthalmitis: clinical features and visual acuity outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:725–731.

5 Rahman W, Hanson R, Westcott M. A rare case of peripartum endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis. Int Ophthalmol. 2011;31:113–115.

6 Smith SR, Kroll AJ, Lou PL, et al. Endogenous bacterial and fungal endophthalmitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2007;47:173–183.

7 Connell PP, O’Neill EC, Fabinyi D, et al. Endogenous endophthalmitis: 10-year experience at a tertiary referral centre. Eye. 2011;25:66–72.

8 Schwartz SG, Flynn HW, Jr., Scott IU. Endophthalmitis: classification and current management. Expert Rev Ophthalmol. 2007;2:385–396.

9 Chhabra MS, Noble AG, Kumar AV, et al. Neisseria meningitidis endogenous endophthalmitis presenting as anterior uveitis. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2007;44:309–310.

10 Jackson TL, Eykyn SJ, Graham EM, et al. Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis: a 17-year prospective series and review of 267 reported cases. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48:403–423.

11 Greenwald MJ, Wohl LG, Sell CH. Metastatic bacterial endophthalmitis: a contemporary reappraisal. Surv Ophthalmol. 1986;31:81–101.

12 Takebayashi H, Mizota A, Tanaka M. Relation between stage of endogenous fungal endophthalmitis and prognosis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;244:816–820.

13 Khan A, Okhravi N, Lightman S. The eye in systemic sepsis. Clin Med. 2002;2:444–448.

14 Kim SJ, Seo SW, Park JM, et al. Bilateral endophthalmitis as the initial presentation of bacterial meningitis. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2009;23:321–324.

15 Shankar K, Gyanendra L, Hari S, et al. Culture proven endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis in apparently healthy individuals. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009;17:396–399.

16 Binder MI, Chua J, Kaiser PK, et al. Endogenous endophthalmitis: an 18-year review of culture-positive cases at a tertiary care center. Medicine. 2003;82:97–105.

17 Okada AA, Johnson RP, Liles WC, et al. Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis: report of a ten-year retrospective study. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:832–838.

18 Anand AR, Madhavan HN, Neelam V, et al. Use of polymerase chain reaction in the diagnosis of fungal endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:326–330.

19 McDonnell PJ, McDonnell JM, Brown RH, et al. Ocular involvement in patients with fungal infections. Ophthalmology. 1985;92:706–709.

20 Okada AA, Johnson RP, Liles WC, et al. Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis: report of a ten-year retrospective study. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:832–838.

21 Major JC, Jr., Engelbert M, Flynn HW, Jr., et al. Staphylococcus aureus endophthalmitis: antibiotic susceptibilities, methicillin resistance, and clinical outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149:278–283.

22 Sparks JR, Recchia FM, Weitkamp JH. Endogenous group B streptococcal endophthalmitis in a preterm infant. J Perinatol. 2007;27:392–394.

23 Torii H, Miyata H, Sugisaka E, et al. Bilateral endophthlamitis in a patient with bacterial meningitis caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae. Ophthalmologica. 2008;222:357–359.

24 Hayasaka K, Nakamura H, Hayakawa K, et al. A case of endogenous bacterial endophthlamitis caused by Streptococcus bovis. Int Ophthalmol. 2008;28:55–57.

25 Montero JA, Ruiz-Moreno JM, Rodriguez AE, et al. Endogenous endophthalmitis by Propionobacterium acnes associated with leflunomide and adalimumab therapy. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2006;16:343–345.

26 Augsten R, Konigsdorffer E, Dawczynski J, et al. [Listeria monocytogenes endophthalmitis.]. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2004;221:1054–1056.

27 Miller JJ, Scott IU, Flynn HW, Jr., et al. Endophthalmitis caused by Bacillus species. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145:883–888.

28 Kawakami H, Sawada A, Mochizuki K, et al. Endogenous Nocardia farcinica endophthalmitis. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2010;54:164–166.

29 Ang M, Jap A, Chee SP. Prognostic factors and outcomes in endogenous Klebsiella pneumoniae endophthalmitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151(2):338–344.

30 Motley WW, 3rd., Augsburger JJ, Hutchins RK, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa endogenous endophthalmitis with choroidal abscess in a patient with cystic fibrosis. Retina. 2005;25:202–207.

31 Tseng CY, Liu PY, Shi ZY, et al. Endogenous endophthalmitis due to Escherichia coli: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:1107–1108.

32 Rishi E, Rishi P, Nandi K, et al. Endophthalmitis caused by Enterococcus faecalis: a case series. Retina. 2009;29:214–217.

33 Balaskas K, Potamitou D. Endogenous endophthalmitis secondary to bacterial meningitis from Neisseria meningitidis: a case report and review of the literature. Cases J. 2009;2:149.

34 Leng T, Flynn HW, Jr., Miller D, et al. Endophthalmitis caused by Proteus species: antibiotic sensitivities and visual acuity outcomes. Retina. 2009;29:1019–1024.

35 Ness T, Pelz K, Hansen LL. Endogenous endophthalmitis: microorganisms, disposition, and prognosis. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2007;85:852–856.

36 Lingappan A, Wykoff CC, Albini TA, et al. Endogenous fungal endophthalmitis: causative organisms, management strategies, and visual acuity outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153:162–166.

37 Walsh TJ. Emerging fungal pathogens: evolving challenges to immunocompromised patients. In: Scheld WM, Armstrong D, Hughes JM. Emerging infections. Washington, DC: ASM Press, 1998. ch. 15

38 Pappas PG, Rex JH, Lee J, et al. A prospective observational study of candidemia: epidemiology, therapy, and influences on mortality in hospitalized adult and pediatric patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:634–643.

39 Menezes AV, Sigesmund DA, Demajo WA, et al. Mortality of hospitalized patients with Candida endopthalmitis. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:2093–2097.

40 Connell PP, O’Neill EC, Amirul Islam FM, et al. Endogenous endophthalmitis associated with intravenous drug abuse: seven-year experience at a tertiary referral center. Retina. 2010;30:1721–1725.

41 Scherer WJ, Lee K. Implications of early systemic therapy on the incidence of endogenous fungal endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:1593–1598.

42 Bross J, Talbot GH, Maislin G, et al. Risk factors for nosocomial candidemia: a case–control study in adults without leukemia. Am J Med. 1989;87:614–620.

43 Donahue SP, Hein E, Sinatra RB. Ocular involvement in children with candidemia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135:886–887.

44 Kaburaki T, Takamoto M, Araki F, et al. Endogenous Candida albicans infection causing subretinal abscess. Int Ophthalmol. 2010;30:203–206.

45 Schiedler V, Scott IU, Flynn HW, Jr., et al. Culture-proven endogenous endophthalmitis: clinical features and visual acuity outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:725–731.

46 Ness T, Pelz K, Hansen LL. Endogenous endophthalmitis: microorganisms, disposition, and prognosis. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2007;85:852–856.

47 Hashemi SB, Shishegar M, Nikeghbalian S, et al. Endogenous Aspergillus endophthalmitis occurring after liver transplantation: a case report. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:2933–2935.

48 Logan S, Rajan M, Graham E, et al. A case of aspergillus endophthalmitis in an immunocompetent woman: intra-ocular penetration of oral voriconazole: a case report. Cases J. 2010;3:31.

49 Weishaar PD, Flynn HW, Jr., Murray TG, et al. Endogenous Aspergillus endophthalmitis: clinical features and treatment outcomes. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:57–65.

50 Jampol LM, Dyckman S, Maniates V, et al. Retinal and choroidal infarction from Aspergillus: clinical diagnosis and clinicopathologic correlations. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1988;86:422–440.

51 Georgala A, Layeux B, Kwan J, et al. Inaugural bilateral aspergillus endophthalmitis in a seriously immunocompromised patient. Mycoses. 2011;54(5):371–465.

52 Rex JH, Larsen RA, Dismukes WE, et al. Catastrophic visual loss due to Cryptococcus neoformans meningitis. Medicine. 1993;72:207–224.

53 Henderly DE, Liggett PE, Rao NA. Cryptococcal chorioretinitis and endophthalmitis. Retina. 1987;7:75–79.

54 Sheu SJ, Chen YC, Kuo NW, et al. Endogenous cryptococcal endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:377–381.

55 Zakka KA, Foos RY, Brown WJ. Intraocular coccidiomycosis. Surv Ophthalmol. 1978;22:313–321.

56 Blumenkranz MS, Stevens DA. Endogenous coccidiodal endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology. 1980;87:974–984.

57 Rodenbiker HT, Ganley JP, Galgiani JN, et al. Prevalence of chorioretinal scars associated with coccidiomycosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981;99:71–75.

58 Stone JL, Kalina RE. Ocular coccidioidomycosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993;116:249–250.

59 Gonzales CA, Scott IU, Chaudhry NA, et al. Endogenous endophthalmitis caused by Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum: a case report and literature review. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:725–729.

60 Cartwright MJ, Promersberger M, Stevens GA. Sporothrix schenckii endophthalmitis presenting as granulomatous uveitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77:61–62.

61 Dellon AL, Stark WJ, Chretien PB. Spontaneous resolution of endogenous Candida endophthalmitis complicating intravenous hyperalimentation. Am J Ophthalmol. 1975;79:648–654.

62 Riddell JIV, Comer GM, Kauffman CA. Treatment of endogenous fungal endophthalmitis: focus on new antifungal agents. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:648–653.

63 Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study Group. Results of the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study: a randomized trial of immediate vitrectomy and of intravenous antibiotics for the treatment of postoperative bacterial endophthalmitis: Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study Group. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113:1479–1496.

64 Briggs MC, McDonald P, Bourke R, et al. Intravitreal penetration of teicoplanin. Eye. 1998;12:252–255.

65 Tappeiner C, Schuerch K, Goldblum D, et al. Combined meropenem and linezolid as a systemic treatment for postoperative endophthalmitis. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2010;227:257–261.

66 Hariprasad SM, Mieler WF, Holz ER. Vitreous and aqueous penetration of orally administered gatifloxacin in humans. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;121:345–350.

67 Hariprasad SM, Shah GK, Mieler WF, et al. Vitreous and aqueous penetration of orally administered moxifloxacin in humans. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:178–182.

68 Park-Wyllie LY, Juurlink DN, Kopp A, et al. Outpatient gatifloxacin therapy and dysglycemia in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1352–1361.

69 Mehlhorn AJ, Brown DA. Safety concerns with fluoroquinolones. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:1859–1866.

70 Sheridan KR, Potoski BA, Shields RK, et al. Presence of adequate intravitreal concentrations of daptomycin after systemic intravenous administration in a patient with endogenous endophthalmitis. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30:1247–1251.

71 Chan WM, Liu DT, Fan DS, et al. Failure of systemic antibiotic in preventing sequential endogenous endophthalmitis of a bronchiectasis patient. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:549–550.

72 Rex JH, Walsh TJ, Sobel JD, et al. Practice guidelines for the treatment of candidiasis: Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:662–678.

73 Darling K, Singh J, Wilks D. Successful treatment of Candida glabrata endophthalmitis with amphotericin B lipid complex (ABLC). J Infect. 2000;40:92–94.

74 Virata SR, Kylstra JA, Brown JC, et al. Worsening of endogenous Candida albicans endophthalmitis during therapy with intravenous lipid complex amphotericin B. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:1177–1178.

75 Griffin JR, Pettit TH, Fishman LS, et al. Blood-borne Candida endophthalmitis. A clinical and pathologic study of 21 cases. Arch Ophthalmol. 1973;89:450–456.

76 Roney P, Barr CC, Chun CH, et al. Endogenous Aspergillus endophthalmitis. Rev Infect Dis. 1986;8:955–958.

77 Lewis H, Aaberg TM, Fary DR, et al. Latent disseminated blastomycosis with choroidal involvement. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988;106:527–530.

78 Blumenkranz MS, Stevens DA. Endogenous coccidiodal endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology. 1980;87:974–984.

79 Lemke A, Kiderlen AF, Kayser O, et al. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;68:151–162.

80 Kinyoun JL. Treatment of Candida endophthalmitis. Retina. 1982;2:215–222.

81 Green WR, Bennett JE, Goos RD. Ocular penetration of amphotericin B: a report of laboratory studies and a case report of post surgical Cephalosporium endophthalmitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1965;73:769–775.

82 Dave VP, Majji AB, Suma N, et al. A rare case of Aspergillus terreus endogenous endophthalmitis in a patient of acute lymphoid leukemia with good clinical outcome. Eye. 2011;25(8):1094–1096.

83 Humphrey MJ, Jevons S, Tarbit MH. Pharmacokinetic evaluation of UK-49,858, a metabolically stable triazole antifungal drug, in animals and humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;28:648–653.

84 Savani DJ, Perfect JR, Cobo LM, et al. Penetration of new azole compounds into the eye and efficacy in experimental Candida endophthalmitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:6–10.

85 Annamalai T, Fong KC, Choo MM. Intravenous fluconazole for bilateral endogenous Candida endophthalmitis. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2011;27:105–107.

86 Christmas NJ, Smiddy WE. Vitrectomy and systemic fluconazole for treatment of endogenous fungal endophthalmitis. Ophthalm Surg Lasers. 1996;27:1012–1018.

87 Luttrull JK, Wan WL, Kubak BM, et al. Treatment of ocular fungal infections with oral fluconazole. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;119:477–481.

88 Urbak SF, Degn T. Fluconazole in the management of fungal ocular infections. Ophthalmologica. 1994;208:147–156.

89 Como JA, Dismukes WE. Oral azole drugs as systemic antifungal therapy. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:263–272.

90 Edwards JE, Jr., Bodey GP, Bowden RA, et al. International conference for the development of a consensus on the management and prevention of severe candidal infections. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:43–59.

91 Ackler ME, Vellend H, McNeely DM, et al. Use of fluconazole in the treatment of candidal endophthalmitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:657–664.

92 van’t Wout JW, Novakova I, Verhagen CA, et al. The efficacy of itraconazole against fungal infections in neutropenic patients: a randomized comparative study with amphotericin B. J Infect. 1991;22:45–52.

93 Como JA, Dismukes WE. Oral azole drugs as systemic antifungal therapy. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:263–272.

94 Pappas PG, Rex JH, Sobel JD, et al. Guidelines for treatment of candidiasis. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:161–189.

95 Scott LJ, Simpson D. Voriconazole: a review of its use in the management of invasive fungal infections. Drugs. 2007;67:269–298.

96 Hariprasad SM, Mieler WF, Holz ER, et al. Determination of vitreous, aqueous, and plasma concentrations of orally administered voriconazole in humans. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:42–47.

97 Biju R, Sushil D, Georgy NK. Successful management of presumed Candida endogenous endophthalmitis with oral voriconazole. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2009;57:306–308.

98 Morris MI. Posaconazole: a new antifungal agent with expanded spectrum of activity. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009;66:225–236.

99 Sponsel WE, Graybill JR, Nevarez HL, et al. Ocular and systemic posaconazole (SCH-56592) treatment of invasive Fusarium solani keratitis and endophthalmitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:829–830.

100 Tu EY, McCartney DL, Beatty RF, et al. Successful treatment of resistant ocular fusariosis with posaconazole (SCH-56592). Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:222–227.

101 Bennett JE. Antimicrobial agents (continued): Antifungal Agents. In: Hardman JG, Limbird LE. Goodman and Gilman’s The pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 10th ed. New York: McGraw–Hill; 2001:1295–1312.

102 Sarria JC, Bradely JC, Habash R, et al. Candida glabrata endophthalmitis treated successfully with caspofungin. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:46–48.

103 Durand ML, Kim IK, D’Amico DJ, et al. Successful treatment of Fusarium endophthalmitis with voriconazole and Aspergillus endophthalmitis with voriconazole plus caspofungin. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:552–554.

104 Kwok AK, Hui M, Panc CP, et al. An in vitro study of ceftazidime and vancomycin concentrations in various fluid media: implications for use in treating endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:1182–1188.

105 Axelrod AJ, Peyman GA, Apple DJ. Toxicity of intravitreal injection of amphotericin B. Am J Ophthalmol. 1973;76:578–583.

106 Payne JF, Keenum DG, Sternberg P, Jr., et al. Concentrated intravitreal amphotericin B in fungal endophthalmitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:1546–1550.

107 Brod RD, Flynn HW, Jr., Clarkson JG, et al. Endogenous Candida endophthalmitis: management without intravenous amphotericin B. Ophthalmology. 1990;97:666–672.

108 Koc A, Onal S, Yenice O, et al. Pars plana vitrectomy and intravitreal liposomal amphotericin B in the treatment of Candida endophthalmitis. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2010 Mar;9:1–3. Epub ahead of print doi: 10.3928/15428877-20100215-35

109 Schulman JA, Peyman G, Fiscella R, et al. Toxicity of intravitreal injection of fluconazole in the rabbit. Can J Ophthalmol. 1987;22:304–306.

110 Velpandian T, Narayanan K, Nag TC, et al. Retinal toxicity of intravitreally injected plain and liposome formulation of fluconazole in rabbit eye. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2006;54:237–240.

111 Urbak SF, Degn T. Fluconazole in the management of fungal ocular infections. Ophthalmologica. 1994;208:147–156.

112 Yoshizumi MO, Banihashemi AR. Experimental intravitreal ketoconazole in DMSO. Retina. 1988;8:210–215.

113 Gao H, Pennesi ME, Shah K, et al. Intravitreal voriconazole: an electroretinographic and histopathologic study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:1687–1692.

114 Kramer M, Kramer MR, Blau H, et al. Intravitreal voriconazole for the treatment of endogenous Aspergillus endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1184–1186.

115 Schulman JA, Peyman GA. Intravitreal corticosteroids as an adjunct in the treatment of bacterial and fungal endophthalmitis: a review. Retina. 1992;12:336–340.

116 Kinyoun JL. Treatment of Candida endophthalmitis. Retina. 1982;2:215–222.

117 Snip RC, Michels RG. Pars plana vitrectomy in the management of endogenous Candida endophthalmitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1976;82:699–704.

118 Jackson TL, Eykyn SJ, Graham EM, et al. Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis: a 17-year prospective series and review of 267 reported cases. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48:403–423.

119 Christmas NJ, Smiddy WE. Vitrectomy and systemic fluconazole for treatment of endogenous fungal endophthalmitis. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 1996;27:1012–1018.

120 Huang SS, Brod RD, Flynn HW, Jr. Management of endophthalmitis while preserving the uninvolved crystalline lens. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;112:695–701.

121 Jackson TL, Eykyn SJ, Graham EM, et al. Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis: a 17-year prospective series and review of 267 reported cases. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48:403–423.