Education and Training in Intensive Care Medicine

Training Aspirations for Intensive Care Medicine

The purpose of any medical education program should be to integrate knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviors within a sound ethical and professional framework that encourages reflective life long learning, with the aim of producing competent and caring practitioners who possess both team-working and leadership capacities. Achieving this objective requires a firm focus on the needs of patients and confident and effective structures and processes for training and education. The American College of Critical Care Medicine states,1 “Critical care medicine trainees and faculty must acquire and maintain the skills necessary to provide state-of-the art clinical care to critically ill patients, to improve patient outcomes, optimize intensive care unit utilization, and continue to advance the theory and practice of critical care medicine. This should be accomplished in an environment dedicated to compassionate and ethical care.” To this statement one could add: using the knowledge and resources of a multiprofessional team and involvement of patients and caregivers.

The Training Environment

Training and service are necessary companions. In the last 20 years, health systems worldwide have seen that patients’ expectations of safe and reliable health care are not always satisfied.2,3 It is reasonable for patients to expect that their care should be delivered by fully trained specialists and not by less experienced individuals or those in training grades. However, this expectation is made difficult to satisfy by cost pressures, rationing, increased throughput, staffing limitations, and reduced hours of work for trainees.4,5 These challenges are a particular problem for acute and emergency care, including critical care,6 but it is in precisely these areas that some of the most innovative solutions can be found.

Physician assistants or extended-role nurse practitioners are now active in many roles. In ICM, the United Kingdom has developed a program for advanced critical care practitioners7 derived from the physicians’ Competency-Based Training in Intensive Care Medicine (CoBaTrICE) program. Critical care and outreach, medical emergency teams,8 and the United Kingdom’s hospital at night and 24/7 teams9 all involve senior nurses with diagnostic and management training. In the United States, growth of the hospitalist movement into a new specialty demonstrates how the clinical demands of acutely ill patients can have an impact on training and education.10 The National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties has developed a national program of competencies that includes diagnostic algorithms and treatment based on protocols,11 and many of the competencies are centered around management of acutely ill or physiologically unstable patients. Acutely ill patients are thus necessarily cared for by multiple teams involving physicians, nurses, and allied health care professionals. Such teams have rapidly changing membership, and colleagues often do not know each other well. Accurate and comprehensive clinical handoffs/handovers need to be standardized in order to ensure continuity of care. This care needs to be supplemented by objective processes that pick up measures of physiologic deterioration, escalate concerns in a timely and appropriate manner, and can call upon the best person at the right time, every time. Training to acquire these complex skills in the acute and emergency care environment must be embedded in undergraduate curricula for all health care professionals.12,13

Current Training in Intensive Care Medicine

In a survey of 41 countries carried out by the CoBaTrICE Collaboration14 under the aegis of the European Society for Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM), 54 different ICM training programs were identified (37 within the European region) that ranged in duration from 3 months to 6 years (most frequently 2 years). Entry criteria were significantly different between some countries with regard to the structure and format of the training program. Nursing surveys demonstrate similar diversity in their training programs. The CoBaTrICE survey was updated for European Region countries in 2009,15 and demonstrated that although progress had been made on convergence in speciality status and shared competencies there were still significant deficiencies in standards for assessment, quality assurance, and infrastructure support for training. Currently 10 European Region countries use the harmonized CoBaTrICE competencies.

Outside the CoBaTrICE program and those countries that have adopted it, few national programs define the outcomes of training explicitly in terms of the competencies expected of a specialist in ICM. There is tacit acknowledgment that the terms “attending,” “consultant,” and “specialist” may have administrative and logistic equivalence within individual countries and that a “good” specialist in one country is likely to be as well equipped with knowledge and skills as a good specialist in another, but there is little evidence to prove this, whereas there is solid evidence that standards of assessment and quality assurance vary widely between countries and even between different speciality programs within countries.15

Specialist status in all these schemes is obtained through some combination of time spent in the program, competency-based assessments, case reports, submission of diploma theses, oral (viva voce) examination, and clinical examination. There does not as yet exist an enforced recertification process specifically for ICM in any country, nor is there an agreed-upon standard for benchmarking intensive care units or training programs against international peers, though such standards are now being developed.16 For example, the United Kingdom has now established a multicollegiate Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine responsible for the new primary specialist training program in ICM, and for standards of revalidation and peer review.17,18

Competency-Based Training

Competencies are a method for describing the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behavior expected of specialists in terms of what they are able to do. Several national regulatory bodies for physicians have started to modify their training programs from syllabus-based, examination-driven systems to programs based on competencies assessed in the workplace, particularly the United Kingdom, Canada (using the CanMEDS framework19), and the United States. The challenge for trainers and trainees is to develop robust methods for workplace-based assessment and to create the necessary flexibility within training programs to allow time-based training to be replaced by programs in which trainees acquire competencies at different rates. This has been made more difficult by limitations on working hours.4,5 The resultant friction between service and training has led to poor use of assessment tools and an increasing belief that excellence in some has been sacrificed for a basic level of competence in many.20

The CoBaTrICE Collaboration was formed in 2003 to harmonize standards of training in ICM internationally, first by defining outcomes of specialist ICM training and then by developing guidance and standards for assessment of competence and program infrastructure and quality assurance.21,22 The underlying principle of this initiative was the concept that an ICM specialist trained in one country should have the same core skills and abilities as one trained in another, thereby ensuring a common standard of clinical competence. This follows the European Union ethos of free movement of professionals and mutual recognition of medical qualifications between member states.23 Competency-based training makes convergence possible by defining the outcomes of specialist training—a common “end product”—rather than enforcing rigid structures and processes of training. A minimum standard of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behavior is defined a priori and applied to existing structures and processes of training; acquisition and assessment of competence occur during training in the workplace.

Defining Core Competencies

The CoBaTrICE project has used consensus techniques—an extensive international consultation process using a modified online Delphi involving more than 500 clinicians in more than 50 countries, an eight-country postal survey of patients and relatives, and an expert nominal group—to define the core competencies required of a specialist in ICM.21,24 These competencies have been linked to a comprehensive syllabus, relevant educational resources, and guidance for the standardized assessment of competence in the workplace via a dedicated website.22 Since its launch in September 2006, 10 national training programs have adopted CoBaTrICE, and others have made use of the materials. In 2008, the second phase of the project developed international standards for national training programs in ICM,16 and further refined the methods of assessment of competence. The implementation and long-term evaluation of the CoBaTrICE program will be necessary to assess its impact on an individual’s competence and harmonization of ICM training. In the United States, a multisociety initiative has used a similar methodology to the CoBaTrICE program to create common competencies.25

Evolving Professional Roles: Implications for Training

The CoBaTrICE Delphi demonstrated the importance that intensive care clinicians attach not only to the acquisition of procedural technical skills but equally to aspects of professionalism—communication skills, attitudes and behavior, governance, team working, and judgment.24 The intensivist is akin to an “acute general practitioner,” a family doctor with enhanced role in acute medicine, physiology, diagnostics, palliative care, research, ethics, and with added technical ability. Most importantly they are the team leaders and orchestrators (and providers) of care, and their competencies must therefore include these team-management, integration-of-care skills. Competency-based training makes this possible by explicitly identifying which skills are shared in common and which are peculiar to specific disciplines. Thus, although weaning from ventilation,26 instigation of renal replacement, nutritional support, prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism, and chest pain management pathways,27 among others, can be nurse led and protocol driven, the intensivist provides a strategic, integrating, and continuity role as much as a technical one. Opportunities for collaboration between critical care physicians and hospitalists can also be clarified in this manner. In this model, hierarchies become flatter, practitioners become more patient focused, and the intensivist’s leadership skills must include the capacity for collaborative decision making while continuing to assume final responsibility for patient care. As nonphysician roles increase and extend, it is essential that their schemes for training be coordinated and better integrated with those for physicians, ideally starting at undergraduate level.28

Practical Implications of Competency-Based Training

Concerns about competency-based training include the perception that competencies describe a “craftsman” rather than a “professional” and that “being a good doctor” is too complex to be defined by lists of skills or activities.29–31 This may be an artificial distinction, because both may aspire to excellence through constant practice and reflection. The professional has the privilege of self-regulation based on defined standards of practice, which emphasizes the importance of revalidation and recertification. The minimum standard for revalidation should include the competencies of a specialist, plus evidence of excellence, which may include the domains of research, teaching, professional development, role modeling, and high-quality patient care demonstrated through processes or outcomes. A minimum safe standard is where professional training starts, not where it ends.

Documentation is a crucial component of training because it provides the evidence on which the trainee makes the case for being accepted as competent or, indeed, excellent. Portfolios are the responsibility of the trainee but require review by the trainer designated as mentor or supervisor for that trainee. It seems likely that most training programs will move from traditional paper-based methods to e-portfolios as technology evolves. This change brings with it both advantages and disadvantages (Box 74.1). A particular advantage of Internet-based technologies is the ability to link competencies and syllabi to the rapidly expanding repository of web-based educational resources.32 They may also make it easier to deliver educational interventions in the workplace during clinical work rather than limiting provision of education to office hours.33

Maintenance of competence has become an increasingly regulated activity for specialists, incorporating the distinct but related processes of accredited continuing medical education (CME) or continuing professional development (CPD), appraisal, revalidation, and recertification or maintenance of certification. Standards for recertification vary widely.34 Several countries now have mandated processes, including Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United States, and from 2013 the United Kingdom. Maintenance of certification in the United States is based on demonstrating competence in six domains,35 and in the United Kingdom in four domains.36 The process for revalidation for intensive care specialists in the United Kingdom has recently been defined.37

Assessment

Workplace-based assessment of competence (Box 74.2)38–46 is not generally problematic for the majority of trainees, but the potential complexity of assessment becomes apparent when there is a trainee in difficulty or when an adverse assessment results in litigation or revelations of serial malpractice later in life. Why was the problem not detected earlier? Whose responsibility is it to undertake assessment? How should it be performed? How often should assessments be made? How reliable and repeatable are the methods used, and how does one deal with disagreement between different trainers?

For any program of training, a system of evaluation must exist to test the validity of the teaching method, the content, and its application. If the curriculum is to have an assessment component, it too requires regular evaluation to ensure that it remains valid, that is, repeatable and consistent between observers. The ultimate test is whether the curriculum and method of testing lead to improvements in health care. Miller’s hierarchy of learning47 suggests that whereas undergraduate training is more focused on the acquisition of knowledge, postgraduate training places increasing importance on performance, and assessment strategies must therefore focus at the “action” level or on “what one does.” Assessments need to take into account the trainees’ abilities and previous experience, the complexity of the tasks that they perform, and the context. In a variation of the Miller pyramid, the route to becoming a true specialist might be a training ladder, with step 1 (the novice) representing the acquisition of knowledge; step 2 (the trainee) the period of training, which will vary in duration and intensity, depending on needs; step 3 (the competent new specialist) indicating independence; and step 4 (the expert) with experience and further training beyond basic competencies. The steps are not truly rigid because in reality, skills and knowledge are learned together and experiences and practice occur at all stages in training. This schema is equally applicable to all disciplines.

Definitions of competencies serve to guide the assessment process. Descriptions of what physicians should be able to do create a benchmark against which judgments can be made of clinical performance (“does,” rather than “can do”). A range of methods and tools may be used to assess training, but assessment of physicians’ performance at work is still in its infancy.48 Assessment must go beyond technical skills to include aspects of professionalism, attitudes, and behavior: communication skills, familiarity with current knowledge, shared decision making, respect for autonomy, and compassion. Techniques for the assessment of holistic professionalism include “360-degree assessment,” also called multisource feedback.49,50 This technique involves actively seeking the opinion of others on the team, both one’s peers and junior colleagues and, where appropriate, patients and relatives, about one’s performance.

During training these assessments should be formative—that is, they should contribute to learning and not be a final pass/fail judgment. This traditional “apprentice-master” model requires frequent observation during routine clinical work by an experienced trainer and works well for the majority of trainees. However, the model may need to be supplemented by formal methods involving more objective assessment of performance. The assessments should be documented in the trainee’s portfolio and combined with annual appraisal. A more novel technique is based on video recording of team behaviors during ward rounds.51

Delivering Training and Assessment in the Workplace: Role of Simulation

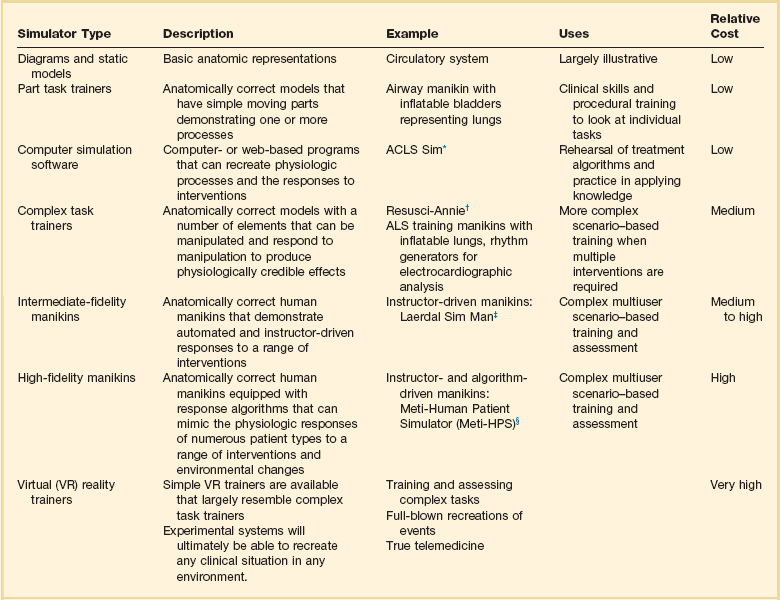

Simulators in health care are not a new concept. The Romans had birthing phantoms made from various leathers and bone to teach midwifery. Indeed early vivisectionists would have claimed operations on animals improved performance of the surgeon when dealing with patients. Simulated clinical environments and patient or equipment simulators have long seemed a highly effective solution to the problems of providing effective individual and team training. Modern medical simulators come in various guises, from simple anatomic models, to part task trainers, to complex virtual reality systems (Table 74.1). However, the most important part of a simulator is not the technology, but the faculty who write the scenario and, more importantly, debrief the students after simulation. Simulated cases lend themselves well to acute care settings. Here, a number of discrete interventions carried out on a single “patient” by various members of the team can be evaluated, subsequently can be viewed in private or during group discussion, and can be of assistance in understanding team working. Rare critical events associated with high rates of mortality or morbidity will not be encountered with sufficient frequency in normal clinical practice for all clinicians to gain proficiency in their avoidance and management, but they can easily be incorporated in simulations. This ability to re create complex and infrequent but highly significant clinical scenarios improves the consistency and repeatability of assessment.

Table 74.1

Categories of Simulators Used in Medicine

ALCS, advanced cardiac life support; ALS, advanced life support.

*ACLS Sim is a computer screen–based Advanced Cardiac Life Support training program that tests applied knowledge of resuscitation treatment algorithms. Further information is available at www.acls.net/sim.htm.

†Resusci-Annie is an ALS trainer manikin made by Laerdal Medical AS, Stavanger, Norway. Further information is available at www.laerdal.com.

‡Sim Man is the universal patient simulator made by Laerdal Medical AS, Stavanger, Norway. Further information is available at www.laerdal.com.

§Meti-HPS is the human patient simulator made by Medical Education Technologies, Inc., Sarasota, FL. Further information is available at www.meti.com.

From Gautam N: Uses of Human Patient Simulators for Critical Care Training [thesis for diploma in intensive care medicine]. London, Intercollegiate Board for Training in Intensive Care Medicine (IBTICM), 2004.

Areas in which simulators are frequently used are the advanced life support courses, the Fundamentals of Critical Care Support course developed by the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM),52 and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine’s PACT (Patient-centered Acute Care Training) program.53

References

1. Dorman, T, Angood, PB, Angus, DC, et al. Guidelines for critical care medicine training and continuing medical education. Crit Care Med. 2004; 32(1):263–272.

2. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2000.

3. Blendon, RJ, DesRoches, CM, Brodie, M, et al. Views of practicing physicians and the public on medical errors. N Engl J Med. 2002; 347:1933–1940.

4. ACGME duty hours requirements. Available at http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/dutyHours/dh_index.asp, 2012. [Accessed June].

5. European working time directive: UK analysis. Available via http://www.nhsemployers.org/planningyourworkforce/MedicalWorkforce/ewtd/Pages/EWTD.aspx, 2012. [Accessed June].

6. Bion, JF, Heffner, J. Improving hospital safety for acutely ill patients. A Lancet quintet. I: Current challenges in the care of the acutely ill patient. Lancet. 2004; 363:970–977.

7. Department of Health, The national education and competence framework for advanced critical care practitioners. Department of Health, London, 2008. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_084011

8. Bellomo, R, Goldsmith, D, Uchino, S. A prospective before-and-after trial of a medical emergency team. Med J Aust. 2003; 179:283–287.

9. MacDonald, R. The hospital at night. BMJ Career Focus. 2004; 328:19s.

10. Goodrich, K, Krumholz, HM, Conway, PH, et al. Hospitalist utilization and hospital performance on 6 publicly reported patient outcomes. J Hosp Med. 2012; 7(6):482–488.

11. National Panel for Acute Care Nurse Practitioner Competencies. Acute Care Nurse Practitioner Competencies. Washington, DC: National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties; 2004.

12. Hall, P, Weaver, L. Interdisciplinary education and teamwork: A long and winding road. Med Educ. 2001; 35:867–875.

13. Perkins, GD, Barrett, H, Bullock, I, et al. The Acute Care Undergraduate Teaching (ACUTE) Initiative: Consensus development of core competencies in acute care for undergraduates in the United Kingdom. Intensive Care Med. 2005; 31:1627–1633.

14. Barrett, H, Bion, JF, on behalf of the CoBaTrICE Collaboration. An international survey of training in adult intensive care medicine. Intensive Care Med. 2005; 31:552–561.

15. The CoBaTrICE Collaboration. The educational environment for competency-based training in intensive care medicine: Structures, processes, outcomes and challenges for trainers and trainees in the European Region. Intensive Care Med. 2009; 35(9):1575–1583.

16. The CoBaTrICE Collaboration. International standards for programmes of training in intensive care medicine in Europe. Special article. Intensive Care Med. 2011; 37:385–393.

17. Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine. Available at http://www.ficm.ac.uk/.

18. Bion, J, Evans, T. The influence of health care reform on intensive care: A UK perspective. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011; 184:1093–1094.

19. Stopponi, MA, Alexander, GL, McClure, JB, et al, Recruitment to a web-based nutrition intervention trial. J Med Internet Res. 2009; 11(3):e38. http://www.royalcollege.ca/public/resources/aboutcanmeds

20. Tooke, J, Aspiring to excellence: Final report of the independent inquiry into modernising medical careers. MMC Inquiry, London, 2008. www.mmcinquiry.org.uk

21. The CoBaTrICE Collaboration. Development of core competencies for an international training programme in intensive care medicine. Intensive Care Med. 2006; 32:1371–1382.

22. CoBaTrICE website. Available at http://www.cobatrice.org, 2012. [Accessed June].

23. Lonbay, J. Reflections on education and culture in European community law. In: Craufurd-Smith R, ed. Culture and European Union Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

24. The CoBaTrICE Collaboration. The views of patients and relatives of what makes a good intensivist: A European survey. Intensive Care Med. 2007; 33:1913–1920.

25. Buckley, JD, Addrizzo-Harris, DJ, Clay, AS, et al. Multisociety task force recommendations of competencies in pulmonary and critical care medicine. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009; 180(4):290–295.

26. Gregory, P, Marelich, GP, Murin, S, et al. Protocol weaning of mechanical ventilation in medical and surgical patients by respiratory care practitioners and nurses: Effect on weaning time and incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest. 2000; 118:459–467.

27. Gomez, MA, Anderson, JL, Karagounis, LA, et al. An emergency department-based protocol for rapidly ruling out myocardial ischemia reduces hospital time and expense: Results of a randomized study (ROMIO). J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996; 28:25–33.

28. Ross, F, Southgate, L. Learning together in medical and nursing training: Aspirations and activity. Med Educ. 2000; 34:739–743.

29. Harden, RM, Crosby, JR, Davis, MH. AMEE Guide 14: Outcome based education: Part 1—An introduction to outcome-based education. Med Teacher. 1999; 21:7–14.

30. Leung, W. Competency based medical training: Review. BMJ. 2002; 325:693–695.

31. Gonczi, A. Review of international trends and developments in competency based education and training. In: Argulles A, Gonczi A, eds. Competency Based Education and Training: A World Perspective. Balderas, Mexico: Noriega Editores, 2000.

32. Kleinpell, R, Ely, EW, Williams, G, et al. Web-based resources for critical care education (review). Crit Care Med. 2011; 39(3):541–553.

33. Almoosa, KF, Goldenhar, LM, Puchalski, J, et al. Critical care education during internal medicine residency: A national survey. J Grad Med Educ. 2010; 2(4):555–561.

34. Peck, C, McCall, M, McLaren, B, et al. Continuing medical education and continuing professional development: International comparisons. BMJ. 2000; 320:432–435.

35. American Board of Medical Specialties Maintenance of Certification. http://www.abms.org/maintenance_of_certification/abms_moc.aspx [Accessed April 2013].

36. General Medical Council (UK). Revalidation. http://www.gmc-uk.org/doctors/revalidation.asp. [Accessed April 2013].

37. Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine. Guidance on CPD and Revalidation. Available at http://www.ficm.ac.uk/cpd-and-revalidation.

38. Modernising Medical Careers, DOPS (Direct Observation of Procedural Skills). Available at http://www.mmc.nhs.uk/pages/assessment/dops, 2007. [Accessed July].

39. Healthcare Assessment and Training, DOPS. Available at http://www.hcat.nhs.uk/assessment/DOPS.htm, 2007. [Accessed July].

40. Modernising Medical Careers, Mini-CEX (Clinical Evaluation Exercise). Available at http://www.mmc.nhs.uk/pages/assessment/minicex, 2007. [Accessed July].

41. Norcini, JJ, Blank, LL, Duffy, FD, et al. The miniCEX: A method for assessing clinical skills. Ann Intern Med. 2003; 138:476–481.

42. TAB. Available at http://www.mmc.nhs.uk/pages/assessment/msf, 2007. [Accessed July].

43. Mini-PAT. Available at http://www.hcat.nhs.uk/assessments/min-epat, 2007. [Accessed July].

44. Ramsey, PG, Wenrich, MD, Carline, JD, et al. Use of peer ratings to evaluate physician performance. JAMA. 1993; 269:1655–1660.

45. Modernising Medical Careers, CbD (Case-based Discussion). Available at http://www.mmc.nhs.uk/pages/assessment/cbd, 2007. [Accessed July].

46. Healthcare Assessment and Training, CbD. Available at http://www.hcat.nhs.uk/assessments/cbd, 2007. [Accessed July].

47. Miller, GE. The assessment of clinical skills and competence/performance. Acad Med. 1990; 65(9 Suppl):S63–S67.

48. Norcini, JJ. Current perspectives in assessment: The assessment of performance at work. Med Educ. 2005; 39:880–889.

49. Evans, R, Elwyn, G, Edwards, A. Review of instruments for peer assessment of physicians. BMJ. 2004; 328:1240.

50. Wilkie, P. Working Group. Multi-Source Feedback, Patient Surveys and Revalidation. Report and Recommendations. London: Academy of Medical Royal Colleges; 2009.

51. Carroll, K, Iedema, R, Kerridge, R. Reshaping ICU ward round practices using video-reflexive ethnography. Qual Health Res. 2008; 18:380.

52. Society of Critical Care Medicine, Fundamentals of Critical Care Support. http://www.sccm.org/Fundamentals/FCCS/Pages/default.aspx.

53. European Society of Intensive Care Medicine Patient Centered Acute Care Training (PACT). http://pact.esicm.org/index.php?ipTested=1