Chapter 4 Drug Interactions

Mechanisms of Drug Interactions

Pharmacokinetic Interactions

Absorption

A given drug may directly reduce the absorption of another drug through the following:

Chelation

Chelation

A chelator is an organic chemical that bonds with and removes free metal ions from solutions. Typically, the molecule being chelated will be a divalent cation (e.g., Ca+2, Mg+2, Fe+2).

A chelator is an organic chemical that bonds with and removes free metal ions from solutions. Typically, the molecule being chelated will be a divalent cation (e.g., Ca+2, Mg+2, Fe+2). There are a few examples of agents that chelate drugs, reducing the absorption of both. The classic example would be tetracycline, which is chelated by calcium. This can inhibit absorption of tetracycline, reducing its antibacterial activity, but perhaps more important, tetracycline can reduce the availability of calcium, which can have dramatic effects on the developing fetus.

There are a few examples of agents that chelate drugs, reducing the absorption of both. The classic example would be tetracycline, which is chelated by calcium. This can inhibit absorption of tetracycline, reducing its antibacterial activity, but perhaps more important, tetracycline can reduce the availability of calcium, which can have dramatic effects on the developing fetus. Binding

Binding

Drugs may also bind other drugs, although this is a relatively rare interaction. The classic example would be cholestyramine, a positively charged drug used to lower cholesterol. It lowers cholesterol by binding to negatively charged bile acids in the gut. Consequently, cholestyramine is also capable of binding other negatively charged drugs in the gut.

Drugs may also bind other drugs, although this is a relatively rare interaction. The classic example would be cholestyramine, a positively charged drug used to lower cholesterol. It lowers cholesterol by binding to negatively charged bile acids in the gut. Consequently, cholestyramine is also capable of binding other negatively charged drugs in the gut.A given drug may also indirectly reduce absorption of another drug, by altering the following:

GI motility

GI motility

The small intestine, with its large surface area, is a key area for drug absorption. Drugs such as anticholinergics, which reduce GI motility, may reduce the rate of absorption by delaying gastric emptying. Slowing the rate of absorption may have an impact on drugs that we want to work quickly, such as analgesics.

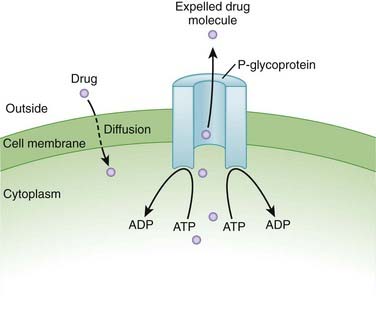

The small intestine, with its large surface area, is a key area for drug absorption. Drugs such as anticholinergics, which reduce GI motility, may reduce the rate of absorption by delaying gastric emptying. Slowing the rate of absorption may have an impact on drugs that we want to work quickly, such as analgesics. Transport proteins, such as P-glycoprotein (Pgp) (Figure 4-1)

Transport proteins, such as P-glycoprotein (Pgp) (Figure 4-1)

Metabolism

Phase I Reactions

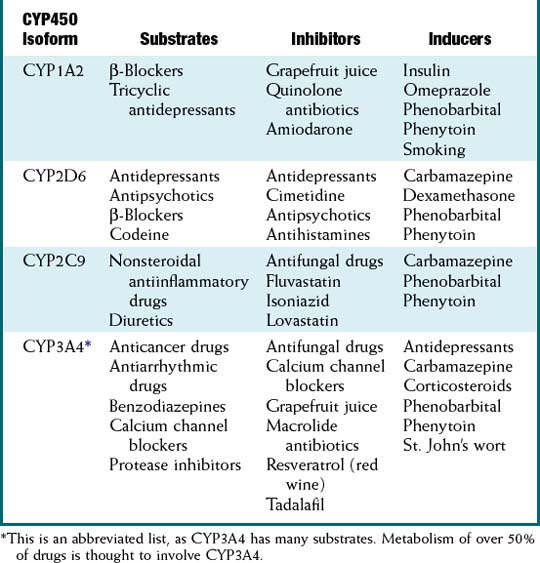

Cytochrome P-450 Enzymes

Clinically significant drug interactions arise from either induction or inhibition of these enzymes.

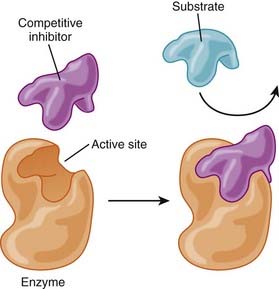

Enzyme Inhibition

Competitive inhibition (Figure 4-2)

Competitive inhibition (Figure 4-2)

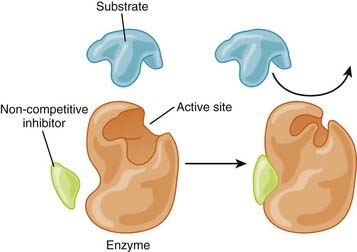

Enzyme Induction

If the drug is inactivated by that enzyme for the purpose of excretion, an inducer will result in reduced circulating levels of active drug. All things being equal, this will likely result in reduced biologic activity of the drug, perhaps leading to therapeutic failure.

If the drug is inactivated by that enzyme for the purpose of excretion, an inducer will result in reduced circulating levels of active drug. All things being equal, this will likely result in reduced biologic activity of the drug, perhaps leading to therapeutic failure. Most cases of induction are allosteric, although rarely a drug may also induce the enzyme system by which it is metabolized.

Most cases of induction are allosteric, although rarely a drug may also induce the enzyme system by which it is metabolized. What would happen if the patient discontinued drug B?

What would happen if the patient discontinued drug B?

Note the effect that enzyme induction will have on a prodrug. If its metabolism is accelerated, more prodrug will be activated, leading to an exaggerated effect, or the exact opposite of what would be seen with drugs that are not prodrugs. See Table 4-1 for a list of common substrates, inhibitors, and inducers of CYP450 enzymes.

Other Metabolic Interactions

Enterohepatic recirculation involves the recycling of drug between the liver and gut.

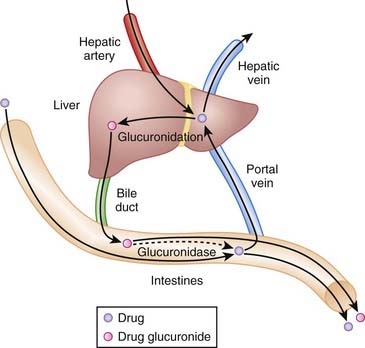

Drugs are inactivated by glucuronidation in the liver. These glucuronides are delivered from the liver via the bile into the intestine, where they are hydrolyzed, releasing the active drug. Active drug can then be reabsorbed in a process known as enterohepatic recirculation. This recirculation prolongs the residence of active drug in the body. Drugs that interfere with enterohepatic recirculation will potentially reduce the activity of any drug that undergoes this process (Figure 4-4).

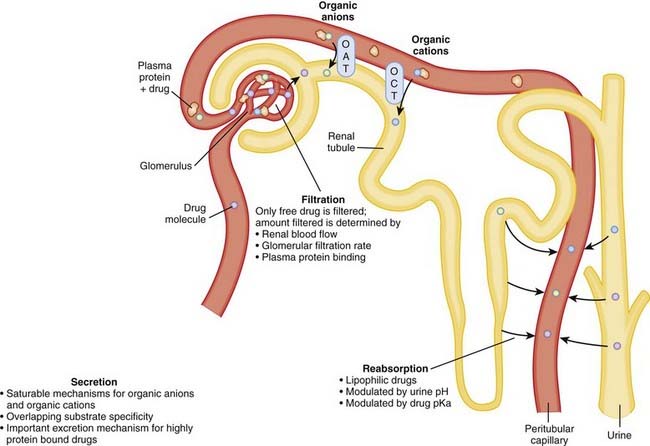

Excretion

In terms of excretion, we are most concerned with drugs that rely on the kidney for their elimination. As these drugs are not inactivated by the liver, inhibiting their excretion will prolong the residence of active drug in the body, potentially leading to an exaggerated (or prolonged) pharmacologic effect (Figure 4-5).

A drug can affect excretion of another drug in various ways:

Pharmacodynamic Interactions

Additive or Synergistic Effects

For example, Ginkgo biloba is an herbal product commonly used as a “memory enhancer,” and as such it is often taken by elderly patients. Among its many effects, Ginkgo inhibits platelet aggregation. Warfarin is an anticoagulant that is very commonly prescribed in the elderly, and combining the two agents can lead to increased bleeding.

For example, Ginkgo biloba is an herbal product commonly used as a “memory enhancer,” and as such it is often taken by elderly patients. Among its many effects, Ginkgo inhibits platelet aggregation. Warfarin is an anticoagulant that is very commonly prescribed in the elderly, and combining the two agents can lead to increased bleeding.Antagonistic Effects

A classic example of two drugs antagonizing the effects of each other is seen when an asthmatic is prescribed salbutamol, a β2 agonist, along with nonselective β-blockers. Propranolol is a β-blocker (see Chapter 11) prescribed for many indications. It works as an antagonist at both β1 and β2 receptors.

A classic example of two drugs antagonizing the effects of each other is seen when an asthmatic is prescribed salbutamol, a β2 agonist, along with nonselective β-blockers. Propranolol is a β-blocker (see Chapter 11) prescribed for many indications. It works as an antagonist at both β1 and β2 receptors.Characteristics of Drug Interactions

Drugs

Nonprescription (Over-the-Counter) Drugs

A common and potentially dangerous assumption is that over-the-counter medications are safer than prescription drugs. Although safety is a consideration when regulatory agencies decide which drugs to approve for over-the-counter sale, there are numerous examples of over-the-counter agents that have the potential to cause harm. In many cases, these harmful effects are caused by drug interactions. Some examples of the more common interacting agents are listed in Table 4-2.

TABLE 4-2 Common Nonprescription Drugs That Are Involved in Drug Interactions

| Drug | Common uses | Mechanism of Interaction |

|---|---|---|

| Cimetidine | Antacid | CYP3A4 inhibitor |

| Omeprazole | Antacid | CYP2C19 inhibitor |

| St. John’s wort | Antidepressant |

Assessing the Clinical Impact of Drug Interactions

Dose

Dose

Frequency

Frequency

As noted earlier, the frequency with which a drug is administered will affect whether an interaction is manageable or not. This is particularly the case with interactions that are acute in nature, such as when two drugs interfere with each other’s absorption. Simply separating the doses of these two drugs so that they do not interact with each other in the stomach can completely negate any interaction.

As noted earlier, the frequency with which a drug is administered will affect whether an interaction is manageable or not. This is particularly the case with interactions that are acute in nature, such as when two drugs interfere with each other’s absorption. Simply separating the doses of these two drugs so that they do not interact with each other in the stomach can completely negate any interaction. Duration

Duration

Not all drugs are taken chronically. A drug interaction between a chronically administered agent and an acutely administered agent can have some distinct issues compared with interactions between two chronically administered agents.

Not all drugs are taken chronically. A drug interaction between a chronically administered agent and an acutely administered agent can have some distinct issues compared with interactions between two chronically administered agents. The advantage of a chronic-acute interaction is that the interaction is short-lived. The classic example is an interaction between a chronic agent and an antibiotic such as erythromycin. Depending on its margin of safety, a temporary interaction such as this might not last long enough to cause enough accumulation to push plasma levels into the toxic range.

The advantage of a chronic-acute interaction is that the interaction is short-lived. The classic example is an interaction between a chronic agent and an antibiotic such as erythromycin. Depending on its margin of safety, a temporary interaction such as this might not last long enough to cause enough accumulation to push plasma levels into the toxic range. A range of inhibition can occur. There are potent enzyme inhibitors and inducers, and relatively weak ones.

A range of inhibition can occur. There are potent enzyme inhibitors and inducers, and relatively weak ones. Drugs may be metabolized by more than one enzyme. The effects of inhibiting one metabolic pathway may be mitigated somewhat by the use of a secondary pathway.

Drugs may be metabolized by more than one enzyme. The effects of inhibiting one metabolic pathway may be mitigated somewhat by the use of a secondary pathway. Genetics likely play an important role. We are just beginning to understand how important a role, but we do know that the severity of the same drug interaction can vary widely among individuals. This is one of the reasons why severe drug interactions are sometimes not detected until a drug has been approved by regulatory agencies for widespread use.

Genetics likely play an important role. We are just beginning to understand how important a role, but we do know that the severity of the same drug interaction can vary widely among individuals. This is one of the reasons why severe drug interactions are sometimes not detected until a drug has been approved by regulatory agencies for widespread use.Strategies for Mitigating Harm from Drug Interactions

The majority of harm that can occur from drug interactions is preventable; the key is knowledge.

Patients are often prescribed drugs that they do not actually need. Prescribers should always set a therapeutic goal first before prescribing a medication, and consider nonpharmacologic options. For example, when a patient has been diagnosed with hypertension, consider lifestyle options first (diet, exercise) before moving to pharmacologic interventions.

Patients are often prescribed drugs that they do not actually need. Prescribers should always set a therapeutic goal first before prescribing a medication, and consider nonpharmacologic options. For example, when a patient has been diagnosed with hypertension, consider lifestyle options first (diet, exercise) before moving to pharmacologic interventions. Numerous over-the-counter medications, including herbal products, interact with prescription drugs. Many jurisdictions do not officially record these agents in a patient’s medication profile; thus unless the patient is interviewed about the nonprescription medications he or she is taking, these drugs will not be taken into account when drug interactions are assessed.

Numerous over-the-counter medications, including herbal products, interact with prescription drugs. Many jurisdictions do not officially record these agents in a patient’s medication profile; thus unless the patient is interviewed about the nonprescription medications he or she is taking, these drugs will not be taken into account when drug interactions are assessed. The adage “start low and go slow” is based on the very simple principle that the lower the plasma levels of a given drug, the less likely problems are to arise from drug interactions that would increase the levels of that drug. A conservative approach such as this also allows the prescriber to assess whether an interaction is occurring and whether changes need to be made. Initiating therapy with a high dose reduces the margin of safety for that drug.

The adage “start low and go slow” is based on the very simple principle that the lower the plasma levels of a given drug, the less likely problems are to arise from drug interactions that would increase the levels of that drug. A conservative approach such as this also allows the prescriber to assess whether an interaction is occurring and whether changes need to be made. Initiating therapy with a high dose reduces the margin of safety for that drug. A list of some common resources is provided in the next section. A key point to remember is that given the large and ever-increasing number of drugs that interact with one another, it is impossible to memorize all of these interactions. Clinicians use resources, typically information technology, to identify interactions and in some cases to provide context around the clinical significance of the interaction.

A list of some common resources is provided in the next section. A key point to remember is that given the large and ever-increasing number of drugs that interact with one another, it is impossible to memorize all of these interactions. Clinicians use resources, typically information technology, to identify interactions and in some cases to provide context around the clinical significance of the interaction.