Chapter 94 Delivery Room Emergencies

Most infants complete the transition to extrauterine life without difficulty; however, a small percentage requires resuscitation after birth. The most common delivery room emergency for neonates is secondary to failure to initiate and maintain effective respirations. Less frequent, but of major importance, are shock (Chapter 92), severe anemia (Chapter 97.1), plethora (Chapter 97.3), convulsions (Chapter 586.7), and management of life-threatening congenital malformations (Chapter 92). Improved perinatal care and prenatal diagnosis of fetal anomalies allow for appropriate maternal transports for high-risk deliveries.

Respiratory Distress and Failure

Disorders of respiration in newborn infants can be categorized as either central nervous system (CNS) failure, representing depression or failure of the respiratory center, or peripheral respiratory difficulty, indicating interference with the alveolar exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide. Cyanosis occurs in both groups (see Table 92-1). Respiratory problems encountered in the delivery room are most frequently those of airway obstruction and depression of the CNS (maternal medications, asphyxia) with an absence of adequate respiratory effort. Respiratory distress in the presence of good respiratory effort should lead to an immediate consideration of the underlying cause and is an indication for radiographic examination of the chest.

If respiratory movements are made with the mouth closed but the infant fails to move air in and out of the lungs, bilateral choanal atresia (Chapter 368) or other obstruction of the upper respiratory tract should be suspected. The mouth should be opened, and the mouth and posterior of the pharynx cleared of secretions with gentle suction. An oropharyngeal airway should be inserted, and the source of the obstruction sought immediately. If effective respiratory flow is not produced by opening the infant’s mouth and clearing the airway, laryngoscopy is indicated. With obstructive malformations of the mandible, epiglottis, larynx, or trachea, an endotracheal tube should be inserted; prolonged endotracheal intubation or tracheostomy may be required. Respiratory failure caused by CNS depression or injury may require continuous mechanical ventilation.

Hypoplasia of the mandible (Pierre Robin, DiGeorge, and other syndromes; Chapters 300 and 303) with posterior displacement of the tongue may result in symptoms similar to those of choanal atresia and may be temporarily relieved by pulling the tongue or mandible forward or placing the infant in the prone position. A scaphoid abdomen suggests a diaphragmatic hernia or eventration, as does asymmetry in contour or movement of the chest or a shift of the apical impulse of the heart; these latter manifestations are also compatible with tension pneumothorax. A pneumothorax can be the presenting symptom in infants with pulmonary hypoplasia, renal malformations, or both.

Pulmonary causes of respiratory difficulty are discussed in Chapter 95.

Neonatal Resuscitation

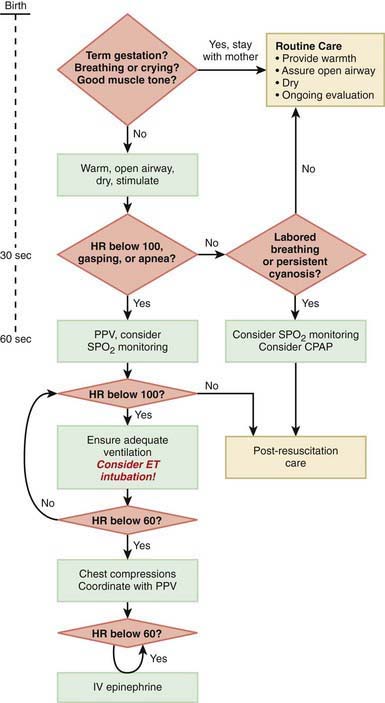

Immediately after birth, an infant in need of resuscitation should be placed under a radiant heater and dried (to avoid hypothermia), positioned with the head down and slightly extended; the airway should be cleared by suctioning, and gentle tactile stimulation provided (slapping the foot, rubbing the back). Simultaneously, the infant’s color, heart rate, and respiratory effort should be assessed (Fig. 94-1).

The steps in neonatal resuscitation follow the ABCs: A, anticipate and establish a patent airway by suctioning and, if necessary, performing endotracheal intubation; B, initiate breathing by using tactile stimulation or positive-pressure ventilation with a bag and mask or through an endotracheal tube; C, maintain the circulation with chest compression and medications, if needed. Steps to follow for immediate neonatal evaluation and resuscitation are outlined in Figure 94-1 (Chapter 62).

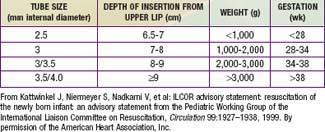

If no respirations are noted or if the heart rate is <100 beats/min, positive pressure ventilation is given through a tightly fitted face bag and mask for 15-30 sec. In infants with severe respiratory depression that does not respond to positive-pressure ventilation via bag and mask, endotracheal intubation should be performed. Many authorities recommend early intubation for extremely low birthweight (ELBW) preterm infants. Guidelines for endotracheal tube size and depth of insertion in infants with different birthweights are shown in Table 94-1. If the heart rate does not improve after 30 sec with bag and mask (or endotracheal) ventilation and remains below 100 beats/min, ventilation is continued and chest compression should be initiated over the lower third of the sternum at a rate of 120 beats/min. The ratio of compressions to ventilation is 3:1. If the heart rate remains <60 beats/min despite effective compressions and ventilation, administration of epinephrine should be considered. Persistent bradycardia in neonates is usually due to hypoxia resulting from respiratory arrest and often responds rapidly to effective ventilation alone. Persistent bradycardia despite what appears to be adequate resuscitation suggests more severe cardiac compromise or inadequate ventilation technique. Poor response to ventilation may be due to a loosely fitted mask, poor positioning of the endotracheal tube, intraesophageal intubation, airway obstruction, insufficient pressure, pleural effusions, pneumothorax, excessive air in the stomach, asystole, hypovolemia, diaphragmatic hernia, or prolonged intrauterine asphyxia.

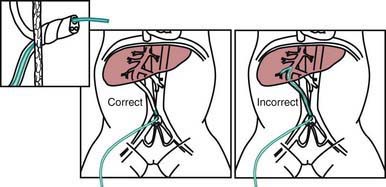

Medications are rarely required but should be administered when the heart rate is <60 beats/min after 30 sec of combined ventilation and chest compressions or during asystole. The umbilical vein can generally be readily cannulated and used for immediate administration of medications during neonatal resuscitation (Fig. 94-2). The endotracheal tube may be used for the administration of epinephrine if intravenous access is not available and/or for naloxone. Epinephrine (0.1-0.3 mL/kg of a 1:10,000 solution, given intravenously or intratracheally) is given for asystole or for failure to respond to 30 sec of combined resuscitation. The dose may be repeated every 3-5 min. Data in neonates are insufficient to recommend higher doses in infants who are unresponsive to the standard dose. Emergency volume expansion is accomplished with 10-20 mL/kg of an isotonic crystalloid solution or type O Rh-negative red blood cells (in acute hemorrhage). Volume infusions should be used cautiously during the resuscitation of a VLBW infant. Sodium bicarbonate (2 mEq/kg, 0.5 mEq/mL of a 4.2% solution) is often given and should be administered slowly (1 mEq/kg/min) if metabolic acidosis has been documented and the resuscitation is prolonged. Sodium bicarbonate should be given only after effective ventilation has been established, because such therapy may increase the blood CO2 concentration and produce respiratory acidosis, complicating an existing metabolic acidosis. Restoration of oxygenation and tissue perfusion is the main treatment of metabolic acidosis associated with asphyxia.

Figure 94-2 Use of the umbilical vein for administration of medications during neonatal resuscitation.

(From Kattwinkel J, Bloom RS, editors: Neonatal resuscitation textbook, ed 5, Elk Grove, IL, 2006, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Heart Association.)

Severe asphyxia may also depress myocardial function and cause cardiogenic shock despite the recovery of heart and respiratory rates. Dopamine or dobutamine administered as a continuous infusion (5-20 µg/kg/min) and fluids should be started after the initial resuscitation effort, to improve cardiac output in an infant with poor peripheral perfusion, weak pulses, hypotension, tachycardia, and poor urine output. Epinephrine (0.1-1.0 µg/kg/min) may be indicated for infants in severe shock that does not respond to dopamine or dobutamine (Chapter 62).

Less severe degrees of poor cardiopulmonary transition in the delivery room can usually be managed by brief periods of bag and mask ventilation. Chest compression and medications are not needed for most neonates who have mild to moderate birth depression. Regardless of the severity of asphyxia or the response to resuscitation, asphyxiated infants should be monitored closely for signs of multiorgan hypoxic-ischemic tissue injury (see Table 93-1).

Shock

Supportive treatment with type O Rh-negative blood or normal saline is indicated for hemorrhage or hypovolemia, respectively. Oxygen should be administered and the metabolic acidosis corrected with sodium bicarbonate. A sympathomimetic agent such as dopamine or dobutamine may be needed to support cardiac output and blood pressure. The diagnosis and treatment of erythroblastosis fetalis are discussed in Chapter 97.2. If infection is present, appropriate antibiotics must be started as soon as possible.

Pneumothorax

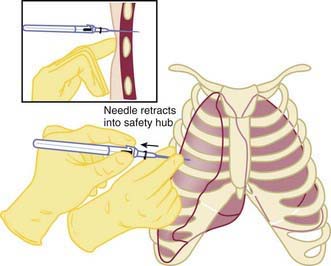

Infants may experience pneumothorax in the delivery room, resulting in respiratory distress and hypoxia. Approximately 1-2% of infants have pneumothorax after birth; only 0.05-0.07% have symptoms (Chapter 95.12). The risk is higher in infants requiring positive pressure ventilation or those with meconium-stained amniotic fluid. Rarely, an infant has a congenital malformation that results in lung hypoplasia, such as congenital diaphragmatic hernia or renal agenesis. Clinically, the infant demonstrates respiratory distress and has diminished breath sounds on the affected side. Transillumination may be helpful to confirm the diagnosis, particularly in the LBW infant. Emergency evacuation of a pneumothorax without radiographic confirmation is indicated in an infant who is unresponsive to resuscitation efforts, and has asymmetric breath sounds, bradycardia, and cyanosis. A 23-gauge butterfly needle or angiocatheter attached to a stopcock and syringe should be inserted perpendicular to the chest wall above the rib in the 4th intercostal space at the level of the nipple (Fig. 94-3). The air is evacuated. The catheter is then inserted with constant negative pressure, and the air evacuated.

Airway Obstruction

Critical fetal and then neonatal airway obstruction represents an emergency in the delivery room. The ex utero intrapartum treatment procedure (EXIT procedure) allows time to secure the airway in an infant known to have airway obstruction for a variety of causes, including laryngeal atresia or stenosis, teratomas, hydromas, and oral tumors, before the infant is separated from the placenta. Uteroplacental gas exchange is maintained throughout the procedure. High-risk perinatal care has led to more frequent prenatal diagnosis of many disorders known to cause the critical high airway obstruction syndrome (CHAOS) (Fig. 94-4).

Abdominal Wall Defects

Appropriate management of patients with abdominal wall defects (omphalocele, gastroschisis) in the delivery room prevents excessive fluid loss and minimizes the risk for injury to the exposed viscera. Gastroschisis is the more common defect and typically the intestines are not covered by a membrane. The exposed intestines should be gently placed in a sterile clear plastic bag after delivery. A membrane often covers an omphalocele, and care should be taken to prevent its rupture. The infant should be transferred to a tertiary referral center for surgical consultation and evaluation for other associated anomalies (Chapter 99).

Injury During Delivery

Viscera

Although adrenal hemorrhage occurs with some frequency, especially after breech delivery, in infants who are large for gestational age or have diabetic mothers, its cause is often undetermined; it may be due to trauma, anoxia, or severe stress, as in overwhelming infection. Ninety percent of adrenal hemorrhages are unilateral; 75% are right-sided. Calcified central hematomas of the adrenal, identified on radiographs or at autopsy in older infants and children, suggest that not all adrenal hemorrhages are immediately fatal. In severe cases, the diagnosis is usually made at postmortem examination. The symptoms are profound shock and cyanosis. A mass may be present in the flank along with overlying skin discoloration; jaundice may also develop. If adrenal hemorrhage is suspected, abdominal ultrasonography may be helpful, and treatment of acute adrenal failure may be indicated (Chapter 569).

Fractures

Extremities

In fractures of the long bones, spontaneous movement of the extremity is usually absent (pseudoparalysis). The Moro reflex is often absent from the involved extremity. Associated nerve involvement may occur. Satisfactory results of treatment of a fractured humerus are obtained with 2-4 wk of immobilization, during which the arm is strapped to the chest, a triangular splint and a Velpeau bandage are applied, or a cast is applied. For fracture of the femur, good results are achieved with traction-suspension of both lower extremities, even if the fracture is unilateral; the legs are immobilized in a spica cast. Splints are effective for treatment of fractures of the forearm or leg. Healing is usually accompanied by excess callus formation. The prognosis is excellent for fractures of the extremities. Fractures in VLBW infants may be related to osteopenia (Chapter 100).

American Heart Association, American Academy of Pediatrics. 2005 American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and emergency cardiovascular care (ECC) of pediatric and neonatal patients: neonatal resuscitation guidelines. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e1029-e1038.

Aschner JL, Poland RL. Sodium bicarbonate: basically useless therapy. Pediatrics. 2008;122:831-835.

Davis PG, Tan A, O’Donnell CPF, Schulze A. Resuscitation of newborn infants with 100% oxygen or air: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2004;364:1329-1333.

DeBacker A, Madern GC, Van de Ven CP, et al. Strategy for management of newborns with cervical teratoma. J Perinat Med. 2004;32:500-508.

Gunn AJ, Bennet L. Is temperature important in delivery room resuscitation? Semin Neonatol. 2001;6:241-249.

Hirose S, Farmer DL, Lee H, et al. The ex utero intrapartum treatment procedure: looking back at the EXIT. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:375-380.

Kattwinkel K, Perlman JM, Aziz K, et al. Neonatal resuscitation: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e1400-e1413.

Lindner W, Vofsbeck S, Hummler H, et al. Delivery room management of extremely low birth weight infants: spontaneous breathing or intubation? Pediatrics. 1999;103:961-967.

Morris LM, Lim FY, Crombleholme TM. Ex utero intrapartum treatment procedure: a peripartum management strategy in particularly challenging cases. J Pediatr. 2009;154:126-131.

Odd DE, Lewis G, Whitelaw A, Gunnell D. Resuscitation at birth and cognition at 8 years of age: a cohort study. Lancet. 2009;373:1615-1622.

Paneth N. The evidence mounts against use of pure oxygen in newborn resuscitation. J Pediatr. 2005;147:4-6.

Perlman JM, Wyllie J, Kattwinkel J, et al. Neonatal resuscitation: 2010 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment Recommendations. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e1319-e1344.

Saugstad OD. Resuscitation of newborn infants: from oxygen to room air. Lancet. 2010;376:1970-1971.

Shih JC, Hsu WC, Chou HC, et al. Prenatal three-dimensional ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of a fetal oral tumor in preparation for the ex-utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) procedure. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;25:76-79.

Vento M, Moro M, Escrig R, et al. Preterm resuscitation with low oxygen causes less oxidative stress, inflammation, and chronic lung disease. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e439-e448.

Wang CL, Anderson C, Leone TA, et al. Resuscitation of preterm neonates by using room air or 100% oxygen. Pediatrics. 2008;121:1083-1089.

Wolkoff LI, Davis JM. Delivery room resuscitation of the newborn. Clin Perinatol. 1999;26:641-658.