Delirium in the postanesthesia care unit

Predisposing and perioperative risk factors

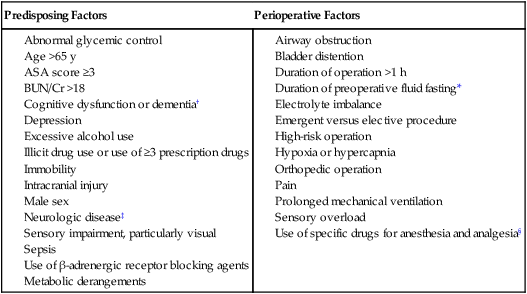

Risk factors for postoperative delirium are summarized in Box 114-1. Patients with no risk factors have a 9% chance of developing postoperative delirium. For those with one or two risk factors, the chance increases to 23%, and for those with three or four risk factors, it’s up to 83%. Multiple hypotheses have been proposed as to why certain individuals are at risk for developing delirium. In elderly patients, contributing factors include smaller brain mass (atrophy) and a decreased number of neurons, as well as decreased neurotransmitter (acetylcholine, serotonin, and dopamine) production and receptor density. Accordingly, the elderly appear to have limited “cognitive reserve.” Therefore, even minor disturbances can lead to postoperative delirium. Specifically, severe illness, cognitive impairment with and without dementia, dehydration, and substance abuse have been shown to be predisposing risk factors. Preexisting diminished executive function and depression are independent predictors of postoperative delirium.

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; BUN/Cr, blood urea nitrogen/creatinine ratio.

†Particularly impairment in executive function.

‡Alzheimer disease and Parkinson disease.

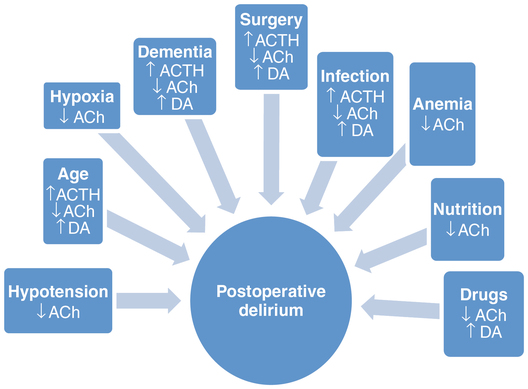

Acetylcholine is important for maintenance of arousal, attention, and memory, whereas dopamine has an opposing effect. Thus, perioperatively administered medications that decrease levels of acetylcholine or increase levels of dopamine can lead to delirium (Figure 114-1). Central anticholinergic syndrome, caused by blockade of muscarinic cholinergic receptors in the central nervous system, manifests as decreased heart rate and contractility, bronchial constriction, decreased salivary secretions, intestinal and bladder contraction, relaxation of sphincters, and delirium. Sedatives, such as benzodiazepines, as well as opioids (especially meperidine because it is structurally similar to the anticholinergic, atropine) are prime contenders. Corticosteroids, H2-receptor antagonists, and anticonvulsants have also been implicated. Renal and hepatic dysfunction compromise clearance of these medications, resulting in further exacerbation of delirium.

Diagnosis

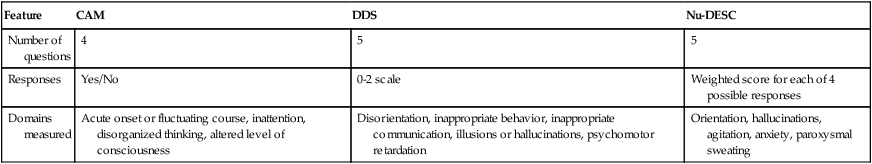

Screening tools have been developed and adapted for use in the PACU to assess patients for the presence of delirium (Table 114-1). The Nursing Delirium Screening Scale appears to be the most sensitive in detecting postoperative delirium, which is largely a diagnosis of exclusion. Common metabolic derangements that are associated with delirium include hyponatremia, hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia, hypokalemia or hyperkalemia, hypercalcemia, hypermagnesemia, lactic acidemia, hypothermia, hypothyroidism, and adrenal insufficiency. Arterial hypoxemia and alveolar hypoventilation are potential respiratory-associated causes of delirium. Postoperative nausea and vomiting and infection (e.g., urinary tract infection, pneumonia, or septicemia) should also be considered in patients who exhibit signs of postoperative delirium.

Table 114-1

Tools Used to Score Delirium in Postanesthesia Care Unit

| Feature | CAM | DDS | Nu-DESC |

| Number of questions | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| Responses | Yes/No | 0-2 scale | Weighted score for each of 4 possible responses |

| Domains measured | Acute onset or fluctuating course, inattention, disorganized thinking, altered level of consciousness | Disorientation, inappropriate behavior, inappropriate communication, illusions or hallucinations, psychomotor retardation | Orientation, hallucinations, agitation, anxiety, paroxysmal sweating |

Prevention

Because the treatment of postoperative delirium is symptomatic, the best approach is prevention. A Cochrane Database review evaluated six randomized clinical trials regarding interventions to prevent delirium and concluded that evidence to support pharmacologic prevention is inadequate. However, identifying high-risk patients by means of a thorough preoperative assessment, including administration of tests that measure depression and cognitive flexibility or executive function, may be helpful in planning the anesthetic and analgesic management. The preoperative assessment should also seek to discern and address potentially modifiable risk factors (see Box 114-1).