Chapter 295 Cysticercosis

Etiology

Humans can be the definitive host (parasite sexual reproduction) as well as the intermediate host (parasite asexual reproduction) of Taenia solium, the pork tapeworm. Infection with the invasive intermediate stage (cysticercus) is called cysticercosis. Unlike Taenia saginata, the intermediate stage of T. solium is invasive with a tropism for the central nervous system (CNS) in humans, causing neurocysticercosis. The risk of cysticercosis may be the same for individuals who eat or do not eat pork, since humans acquire the intermediate form by ingestion of food or water contaminated with the eggs of T. solium. By contrast, consumption of infected undercooked pork produces intestinal infection with the adult worm (Chapter 294). Individuals harboring an adult worm may infect themselves with the eggs by the fecal-oral route. Reverse peristalsis in the small intestine has also been implicated as a means of autoinfection. In the small intestine, the egg releases an oncosphere that crosses the gut wall and spreads hematogenously to many tissues, primarily brain and muscle. Wherever the eggs lodge, they produce small (0.2-0.5 cm) fluid-filled bladders containing a single protoscolex, the juvenile-stage parasite.

Diagnosis

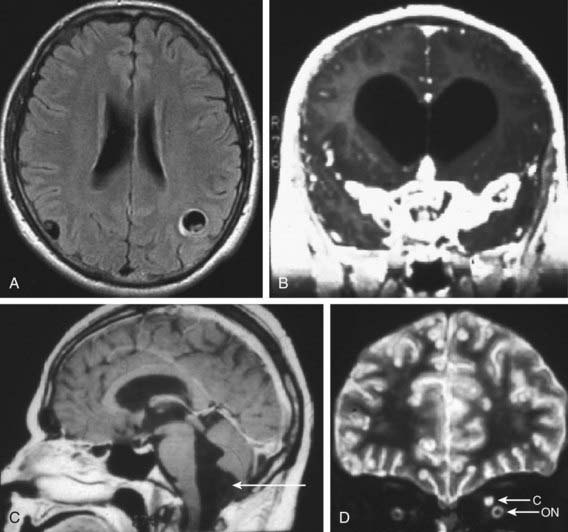

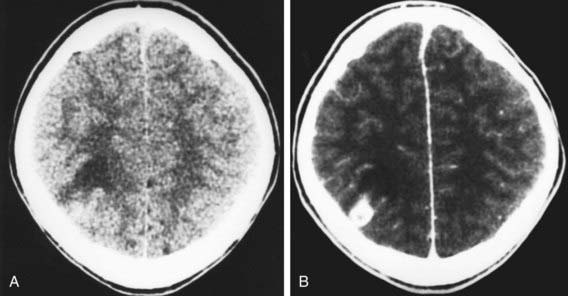

The most useful diagnostic study for parenchymal disease is MRI of the head. MRI provides the most information about cyst viability and associated inflammation. The protoscolex is sometimes visible within the cyst, which provides a pathognomonic sign for cysticercosis (Fig. 295-1A). The MRI also better detects basilar arachnoiditis (Fig. 295-1B), intraventricular cysts (Fig 295-1C), as well as those in the spinal cord. CT is best for identifying calcifications. A solitary parenchymal cyst, with or without contrast enhancement, and numerous calcifications are the most common findings in children (Fig. 295-2). Plain films may reveal calcifications in muscle or brain consistent with cysticercosis, but these are often nondiagnostic in children and may also be found in congenital toxoplasmosis.

Differential Diagnosis

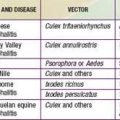

Neurocysticercosis can be confused clinically with encephalitis, stroke, meningitis, and many other conditions (Table 295-1). Clinical suspicion is based on travel history or a history of contact with an individual who might carry an adult tapeworm. On imaging studies, cysticerci can be difficult to distinguish from tuberculomas, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, toxoplasmosis, sarcoidosis, vasculitis, and tumor.

Table 295-1 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF NEUROCYSTICERCOSIS ON NEUROIMAGING

SINGLE NON-ENHANCING CYSTIC LESION

Hydatid disease

Arachnoid cysts

Porencephaly

Cystic astrocytoma

Colloid cyst (third ventricle)

SEVERAL NON-ENHANCING CYSTIC LESIONS

Multiple metastases

Hydatid disease (rare)

ENHANCING LESIONS

Tuberculosis

Mycosis

Toxoplasmosis

Abscess

Early glioma

Metastasis

Arteriovenous malformation

CALCIFICATIONS

Tuberous sclerosis

Tuberculosis

Cytomegalovirus infection

Toxoplasmosis

From Garcia HH, Gonzalez AE, Evans CAW, et al: Taenia solium cysticercosis, Lancet 361:547–556, 2003.

Treatment

The initial objectives of the management of cysticerosis are to diagnosis and manage hydrocephalus due to ventricular obstruction. The next is to control seizure activity. Most associated seizures can be readily controlled using standard anticonvulsant regimens. If seizures are recurrent or associated with calcified lesions, treatment should be continued for 2-3 yr before attempting weaning from anticonvulsants. The inclusion of antiparasitic drugs is controversial, but evidence appears to increasingly point to benefit in certain cases. Causes other than cysticercosis, especially tuberculoma, must be excluded (see Table 295-1).

Abba K, Ramaratnam S, Ranganathan IN: Anthelmintics for people with neurocysticercosis (review), Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3:CD000215, 2010.

Del Brutto OH, Roos KL, Coffey CS, et al. Meta-analysis: cysticidal drugs for neurocysticercosis: albendazole and praziquantel. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:43-51.

Mazumdar M, Pandharipande P, Poduri A. Does albendazole affect seizure remission and computed tomography response in children with neurocysticercosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Child Neurol. 2007;22:135-142.

Nash TE, Singh G, White AC, et al. Treatment of neurocysticercosis: current status and future research needs. Neurology. 2006;67:1120-1127.

Serpa JA, Graviss EA, Kass JS, et al. Neurocysticercosis in Houston, Texas. Medicine. 2011;90(1):81-86.

Serpa JA, Yancey LS, White ACJr. Review. Advances in the diagnosis and management of neurocysticercosis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2006;4:1051-1061.