CHAPTER 180 Craniopagus Twins

Historical Perspective

The first documented illustration of craniopagus twins dates from the 15th century, describing a set born in Bavaria, Germany, in 1491 as a “warning from God” (Fig. 180-1). A famous case of craniopagus parasiticus was reported by Sir Everard Home1 (1756-1832) in his collected works as the “Boys of Bengal,” a set of twins born in India in the 1770s (Fig. 180-2). In the early 19th century it became quite popular to exhibit conjoined twins in traveling road shows and circuses as “freaks” of nature and even to distribute postcards and autographed pictures of them (Fig. 180-3).

Classification and Demographics

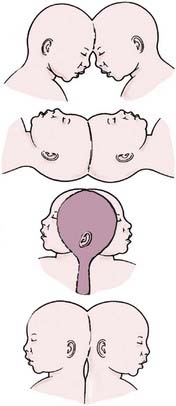

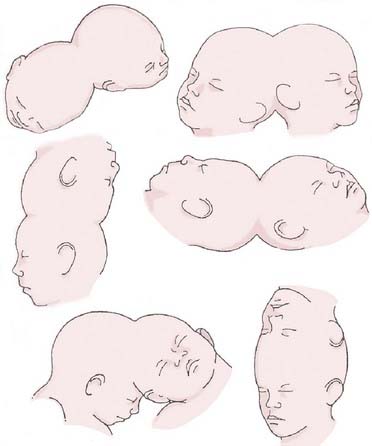

In his fundamental work on teratology, Forster2 introduced the term craniopagus to describe twins joined at the head. Craniopagus twins are defined by a union of the calvaria only; unions involving the foramen magnum, skull base, vertebrae, or face are classified separately (e.g., cephalopagus, parapagus, rachipagus, diprosopus) (Fig. 180-4).3 In craniopagus twinning, the union is rarely symmetrical and may involve any portion of the head. An infinite number of configurations can occur, based on the attachment location and the degree of individual rotation of one head on the other. Variations in the degree of conjoining or sharing of underlying structures such as the meninges, venous sinuses, and cortex add to the individual nature of each case.

FIGURE 180-4 Variations of the union in craniopagus twins.

(Redrawn from Spencer R. Conjoined Twins: Developmental Malformations and Clinical Implications. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2003).

Several authors, beginning with O’Connell,4 have attempted to classify the numerous phenotypic variations seen in craniopagus twins. According to O’Connell’s classification schema, partial craniopagus twins have limited surface area affected, with intact crania or minimal cranial defects. Total craniopagus twins share an extensive surface area with widely connected cranial cavities. O’Connell4 subclassified “vertical” craniopagus twins—”parietal craniopagus,” according to the classification of Bucholz and associates5 (Fig. 180-5)—into types I through III, based on the degree of rotation of one on the other. Stone and Goodrich,6 in an effort to evaluate outcomes among different types of twins, used the partial and total divisions described by O’Connell and also defined two main subtypes: angular and vertical. Angular craniopagus twins have an intertwin longitudinal angle less than 140 degrees, regardless of axial rotation. Vertical craniopagus twins display a continuous longitudinal cranium and are further subdivided based on the degree of intertwin axial facial rotation: type I, rotation less than 40 degrees (formerly O’Connell type I); type II, rotation between 140 and 180 degrees (O’Connell type II); and type III (“intermediate”), rotation between 40 and less than 140 degrees (O’Connell type III).6

Craniopagus twins are extremely uncommon, occurring once in every 0.6 to 2.5 million live births (Table 180-1).6,7 The cause of the conjoining of twins is unclear; both “incomplete fission” and “fusion” hypotheses have been proposed by embryologists.3,8 There are no known environmental or genetic factors. Interestingly, the female-to-male ratio is nearly 4 : 1, although this has not been correlated with any cause of the condition.

TABLE 180-1 Demographic and Embryologic Characteristics of Craniopagus Twins

| INCIDENCE |

An extensive review of the literature from 1919 through 2006 notes 64 well-documented cases of craniopagus with 41 separation attempts—29 performed as single-stage separations and 12 as multistaged separations.9

Surgical Separation

Risk Stratification

The decision to separate craniopagus twins is obviously fraught with serious considerations. Stone and Goodrich6 proposed their classification system in part to better understand the outcomes after surgical separation. It is now recognized that shared dural venous sinuses present significant difficulties when proceeding with separation, but numerous other risk factors must be assessed when evaluating craniopagus twins for separation. Critical to the surgical decision-making process is an understanding of the degree of shared scalp, calvaria, and dura (independent dural envelopes or incomplete dural separation); the amount of separation, interdigitation, or fusion of cortex or deeper structures; the extent of shared arterial connections and cross-flow; the extent of shared or common venous sinuses and drainage; the presence of paired or separate venous outflow; the presence or absence of independent deep venous drainage; and the presence of common or separate ventricular systems and hydrocephalus.10 Because each of these factors has serious implications for the surgical strategy, we proposed a scheme by which individual cases can be evaluated to determine the surgical risk (Table 180-2).10 Although each case involves many unique considerations, this scheme, which assigns point values based on the aforementioned criteria, can be used to gain a preliminary understanding of the degree of risk associated with a separation attempt; a higher score is indicative of a more difficult separation.

| CHARACTERISTIC | SCORE* |

|---|---|

| Scalp | |

| Minor surface area shared (<10 cm2) | 1 |

| Major surface area shared (>10 cm2) | 2 |

| Calvaria | |

| Minor surface area shared (<10 cm2) | 1 |

| Major surface area shared (>10 cm2) | 2 |

| Dura Mater | |

| Independent dural envelope surrounds cortex | 1 |

| Dura shared along one or more planes | 2 |

| Neural Tissue | |

| Completely separate | 1 |

| Interdigitated but not fused | 2 |

| Minor areas of fusion (<5 cm2 total surface area) | 3 |

| Major areas of fusion or involvement of eloquent cortex (>5 cm2 total surface area) | 4 |

| Arterial Connections | |

| None | 1 |

| Minor feeding branches (M4, A4, P4) | 2 |

| Distal branches (M3, A3, P3) | 3 |

| Proximal branches (M2, A2, P2) | 4 |

| Major vascular trunks (M1, A1, P1, ICA) | 5 |

| Venous Connections | |

| None | 1 |

| Separation of major sinuses with minor shared draining veins | 2 |

Shared along anterior  of superior sagittal sinus and/or shared distal (transverse/sigmoid) of superior sagittal sinus and/or shared distal (transverse/sigmoid) |

3 |

Shared along posterior  of superior sagittal sinus without involvement of the torcula of superior sagittal sinus without involvement of the torcula |

4 |

Shared along posterior  of superior sagittal sinus with involvement of the torcula of superior sagittal sinus with involvement of the torcula |

5 |

| Deep Venous Drainage | |

| Present | 1 |

| Absent | 2 |

| Cerebrospinal Fluid (Ventricular Anatomy) | |

| Separate ventricular systems | 1 |

| Shared ventricular system | 2 |

| Venous Outflow | |

| Ipsilateral | 1 |

| Contralateral (crossed) | 2 |

| Arterial Flow | |

| Ipsilateral | 1 |

| Contralateral (crossed) | 2 |

A, anterior cerebral arteryica; ICA, internal cerebral artery; M, middle cerebral artery; P, posterior cerebral artery.

* Higher score equates with more difficult separation. Minimum score = 10; maximum score = 28.

From Browd SR, Goodrich JT, Walker ML. Craniopagus twins. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008;1:1-20.

Preoperative Assessment

New techniques for image reconstruction and flow modeling have provided surgeons with valuable tools to examine critical neural and vascular structures in patients and develop detailed preoperative plans.11–15 Because of the unique anatomy with regard to the sharing of critical and noncritical structures, the goal of imaging is to define the patients’ anatomy—especially the vascular anatomy, with particular attention paid to the venous sinuses. Early computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data allow a preliminary understanding of the extent of fusion and the complexity of the shared arterial and venous architecture, whereas later imaging can provide more extensive modeling of the critical structures for surgical planning.

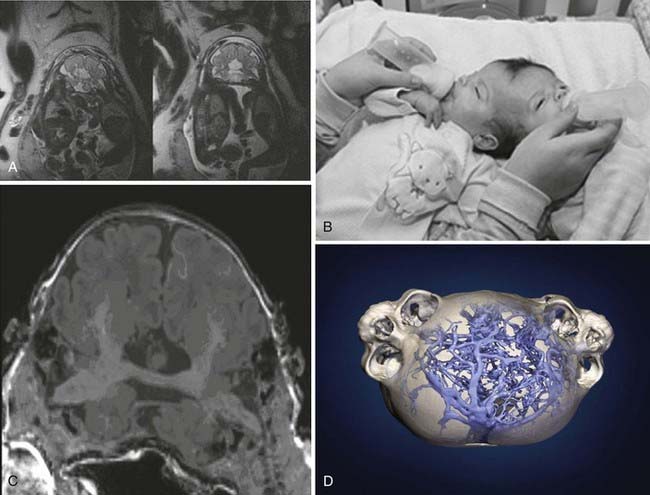

Recent cases have benefited from the ability to create detailed acrylic three-dimensional models based on imaging studies (Fig. 180-6). High-resolution digital reconstructions of CT images of the head can be used to develop three-dimensional models to assess the degree of bony fusion. Information from the bony architecture is used to develop the surgical corridor, site of separation, and plan for postseparation reconstruction of the cranial vault. Newer helical CT scanners can also provide high-resolution angiography that complements traditional digital subtraction angiography.

Single-Stage Separation

There has been limited success with single-stage separation as reported by other groups.16 Generally, the surgery is undertaken as a surgical tour de force in which the length of cases often surpasses 20 to 30 hours. Single-stage separation attempts are predicated on the twins’ ability to handle independent venous drainage immediately at the time of separation. Cases in which reconstruction of the sagittal sinus was attempted have been described,9 but these efforts are rarely successful because of the complexity of this procedure and the instant change in hemodynamic forces and stresses that occur when trying to bypass the entire cerebral venous outflow. Given the complexity of these cases and the difficulty of predicting the suitability of individual venous outflow, which must function immediately on separation, we favor a staged surgical approach.

Theory of Staged Separation

Shared venous anatomy is the cause of the majority of surgical morbidity encountered in modern separation attempts.4 Until recently, death or insurmountable neurological deficits were expected in one twin because of the devastating bleeding that can occur during separation of the shared dural venous sinuses. In these cases, the surviving twin was the one who received the entire superior sagittal sinus during separation, because there was no way during single-stage surgery to prepare the other twin for the loss of this drainage.

Because of the slow process of collateralization, a staged separation generally takes many months from the initial procedure to final separation. Each case is unique, so the exact timing and length of the process vary. Six to eight procedures involving circumferential craniotomies and arterial-venous ligations are generally undertaken, with 1 to 2 months between surgeries, before the final separation surgery.17

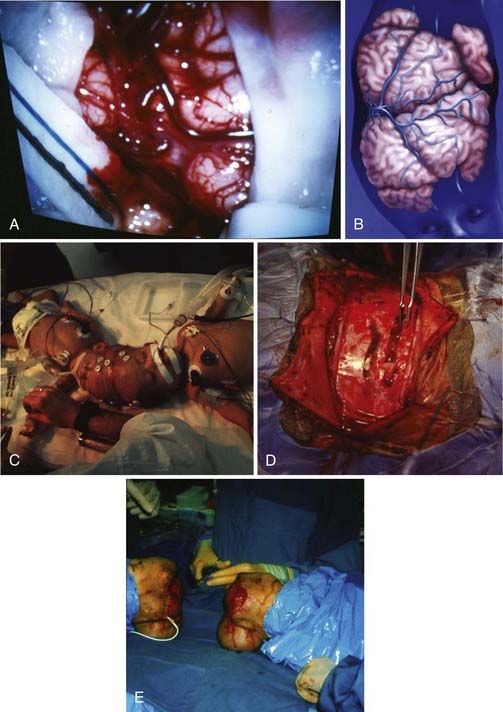

Surgical Techniques

During the preliminary surgeries, several bridging veins are selected for pruning in the donor twin (Fig. 180-7). Initially, temporary clips are placed across a bridging vein, and the venous drainage field is monitored for evidence of hypertension. Alternative bridging veins are selected for pruning, or the procedure is aborted, if brain edema occurs or marked cortical erythema develops. Only a couple of bridging veins are ligated at each surgery to allow the development of alternative deep venous collaterals. After each of the surgeries, repeat imaging is performed to look for evidence of alterations in the venous structures as the donor twin is disconnected from the shared sinus. These pruning surgeries are continued until the donor twin is completely disconnected from the shared sinus and the final separation surgery can be undertaken.

Risks and Complications

Another issue associated with staged procedures is the need for the surgeon to know at all times the overall anatomic location of the circumferential sinus and to have a conception of where the final ligation will occur.17 Placing Silastic sheets between adjacent cortical areas can help preserve natural tissue planes and provide a means for reorientation at the time of repeated procedures.18

Large defects created by the separation often need to be surgically repaired for a good functional and cosmetic outcome. Reconstruction involves multiple anatomic structures, including the dura, calvaria, and scalp. Dura is reconstructed with a variety of allograft products, including onlay allograft dural substitutes. Large calvarial defects may be left open after the initial or subsequent separation surgeries; however, the use of split-thickness autograft or the later fabrication of custom methyl methacrylate cranioplasties can lead to good cosmetic reconstructions of the cranial vault. The use of tissue expanders during multiple surgical procedures allows the growth of additional scalp and reduces the need to incorporate rotational or transpositional flaps.18 Although some have reported the long-term (3- to 6-month) use of tissue expanders before a single separation procedure,19 we advise delaying the placement of tissue expanders during staged separations until the penultimate procedure to avoid the common complication of infection.

Despite the absence of major portions of the dura mater, falx, and superior sinuses, craniopagus twins do not present with hydrocephalus, indicating that cerebrospinal fluid is adequately reabsorbed.20 As surgical separation progresses, however, the absorptive capacity may be altered in one or both twins, requiring cerebrospinal fluid diversion. Routine postoperative scanning with CT and MRI can provide evidence of hydrocephalus, and shunt placement can be performed as the need arises.

Nonoperable Craniopagus

Illustrative Case

Craniopagus Twins with Conjoined Brain Bridge

In this case, a set of angular craniopagus twins joined side to side, with conjoined parietal-occipital regions, was diagnosed by prenatal ultrasonography. Extensive vascular and neurological imaging studies revealed that their brains were conjoined by a central diencephalic bridge (Fig. 180-8). Because of the severity of the conjoining at the diencephalon, the morbidity and mortality risks were considered unacceptably high, and separation was not performed.

Illustrative Case

Effect of Cultural Views on Craniopagus Management

This case illustrates the complex social and regional philosophical views that can complicate craniopagus management. These nonoperable craniopagus twins had a partial angular frontal configuration (Fig. 180-9). They were diagnosed prenatally by ultrasonography and delivered via elective cesarean section. The children were conjoined at the forehead with a shared anterior fontanelle, and both were neurologically intact. Because of financial limitations and cultural prejudice against conjoined twins in the family’s community, imaging studies were not done until the 24th day of life. CT ultimately showed that the cerebrum and cerebellum of twin B were better developed than those of twin A and that the frontal lobes were fused. By day 25, twin B developed respiratory distress, which led to cardiac arrest. The premature death of twin B necessitated an emergency separation attempt, which was unsuccessful. Although it is unlikely that the outcome would have been different, the complex cultural and social issues that complicated the neurosurgical management of this set of craniopagus twins cannot be overstated.

Acknowledgment

This chapter is based on articles by Walker and Browd18 and Browd and colleagues.10 Readers are referred to these sources for further information on the history and management of craniopagus twins.

Bancovsky I, Bianco E, Moreira FA. Computed tomography in craniopagus occipitalis twins. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1979;3:836-837.

Browd SR, Goodrich JT, Walker ML. Craniopagus twins. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008;1:1-20.

Bucholz RD, Yoon KW, Shively RE. Temporoparietal craniopagus. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1987;66:72-79.

Forster A. Die Missbildungen des Menschen Systematisch Dargestellt. Nebst einem Atlas vban 26 Tafeln mit Erlautenungen. Zweite vollstandige Ausgabe. Jena: Friedrich Manke; 1865.

Home E. Lectures on Comparative Anatomy; in which are explained the preparations in the Hunterian Collection. London, UK: G. & W. Nichol; 1814-1828.

Jansen O, Mehrabi VA, Sartor K. Neuroradiological findings in adult cranially conjoined twins. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1998;89:635-639.

Kaufman MH. The embryology of conjoined twins. Childs Nerv Syst. 2004;20:508-525.

Khan ZH, Hamidi S, Miri SM. Craniopagus, Laleh and Ladan twins, sagittal sinus. Turk Neurosurg. 2007;17:27-32.

Kingston CA, McHugh K, Kumaradevan J, et al. Imaging in the preoperative assessment of conjoined twins. Radiographics. 2001;21:1187-1208.

Marcinski A, Lopatec HU, Wermenski K, et al. Angiographic evaluation of conjoined twins. Pediatr Radiol. 1978;6:230-232.

O’Connell JE. Craniopagus twins: surgical anatomy and embryology and their implications. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1976;39:1-22.

Potter EL. Pathology of the Fetus and Infant, ed 2. Chicago: Year Book Medical; 1961.

Roberts T. Cephalopagus twins. Hoffman, Epstein . Disorders of the Developing Nervous System: Diagnosis and Rreatment. Boston: Blackwell Scientific. 1986; pp. 255-266.

Rutka JT, Souweidane M, ter Brugge K, et al. Separation of craniopagus twins in the era of modern neuroimaging, interventional neuroradiology, and frameless stereotaxy. Childs Nerv Syst. 2004;20:587-592.

Shively RE, Bermant MA, Bucholz RD. Separation of craniopagus twins utilizing tissue expanders. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;76:765-773.

Spencer R. Conjoined Twins: Developmental Malformations and Clinical Implications. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2003.

Stone JL, Goodrich JT. The craniopagus malformation: classification and implications for surgical separation. Brain. 2006;129:1084-1095.

Swift DM, Weprin B, Sklar F, et al. Total vertex craniopagus with crossed venous drainage: case report of successful surgical separation. Childs Nerv Syst. 2004;20:607-617.

Walker M, Browd SR. Craniopagus twins: embryology, classification, surgical anatomy, and separation. Childs Nerv Syst. 2004;20:554-566.

Winston KR. Craniopagi: anatomical characteristics and classification. Neurosurgery. 1987;21:769-781.

1 Home E. Lectures on Comparative Anatomy; in which are explained the preparations in the Hunterian Collection. London, UK: G. & W. Nichol; 1814-1828.

2 Forster A. Die Missbildungen des Menschen Systematisch Dargestellt. Nebst einem Atlas vban 26 Tafeln mit Erlautenungen. Zweite vollstandige Ausgabe. Jena: Friedrich Manke; 1865.

3 Spencer R. Conjoined Twins: Developmental Malformations and Clinical Implications. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2003.

4 O’Connell JE. Craniopagus twins: surgical anatomy and embryology and their implications. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1976;39:1-22.

5 Bucholz RD, Yoon KW, Shively RE. Temporoparietal craniopagus. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1987;66:72-79.

6 Stone JL, Goodrich JT. The craniopagus malformation: classification and implications for surgical separation. Brain. 2006;129:1084-1095.

7 Potter EL. Pathology of the Fetus and Infant, ed 2. Chicago: Year Book Medical; 1961.

8 Kaufman MH. The embryology of conjoined twins. Childs Nerv Syst. 2004;20:508-525.

9 Khan ZH, Hamidi S, Miri SM. Craniopagus, Laleh and Ladan twins, sagittal sinus. Turk Neurosurg. 2007;17:27-32.

10 Browd SR, Goodrich JT, Walker ML. Craniopagus twins. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008;1:1-20.

11 Bancovsky I, Bianco E, Moreira FA. Computed tomography in craniopagus occipitalis twins. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1979;3:836-837.

12 Jansen O, Mehrabi VA, Sartor K. Neuroradiological findings in adult cranially conjoined twins. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1998;89:635-639.

13 Kingston CA, McHugh K, Kumaradevan J, et al. Imaging in the preoperative assessment of conjoined twins. Radiographics. 2001;21:1187-1208.

14 Marcinski A, Lopatec HU, Wermenski K, et al. Angiographic evaluation of conjoined twins. Pediatr Radiol. 1978;6:230-232.

15 Rutka JT, Souweidane M, ter Brugge K, et al. Separation of craniopagus twins in the era of modern neuroimaging, interventional neuroradiology, and frameless stereotaxy. Childs Nerv Syst. 2004;20:587-592.

16 Swift DM, Weprin B, Sklar F, et al. Total vertex craniopagus with crossed venous drainage: case report of successful surgical separation. Childs Nerv Syst. 2004;20:607-617.

17 Roberts T. Cephalopagus twins. Hoffman, Epstein . Disorders of the Developing Nervous System: Diagnosis and Treatment. Boston: Blackwell Scientific. 1986. pp. 255-266

18 Walker M, Browd SR. Craniopagus twins: embryology, classification, surgical anatomy, and separation. Childs Nerv Syst. 2004;20:554-566.

19 Shively RE, Bermant MA, Bucholz RD. Separation of craniopagus twins utilizing tissue expanders. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;76:765-773.

20 Winston KR. Craniopagi: anatomical characteristics and classification. Neurosurgery. 1987;21:769-781.