Conjunctiva

Normal Anatomy

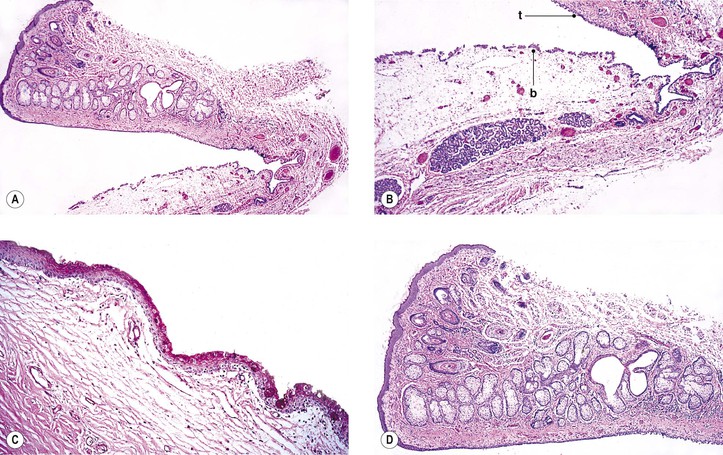

I. The conjunctiva (Fig. 7.1) is a mucous membrane, similar to mucous membranes elsewhere in the body, whose surface is composed of nonkeratinizing squamous epithelium, intermixed with goblet (mucus) cells, Langerhans’ cells (dendritic-appearing cells expressing class II antigen), and occasional dendritic melanocytes.

A. Idiopathic stem cell deficiency is rare, most commonly found in women, and may be familial in some cases. Patients exhibit severe photophobia and, on clinical examination, have corneal vascularization accompanied by loss of the limbal palisades of Vogt, hazy peripheral corneal epithelium, and the presence of conjunctival goblet cells by impression cytology.

A conjunctivalized pannus may develop on the cornea of those with total limbal stem cell deficiency. Characterization of this tissue demonstrates that it is not corneal, as evidenced by failure to stain for cornea-specific K12 mRNA and protein, but rather, it is conjunctival, as evidenced by the presence of goblet cells, the weak expression of K3, and the strong expression of K19.

B. The homeostasis of the conjunctiva is dependent, in part, on the maintenance of a normal tear film, which is composed of lipid, aqueous, and mucoid layers (the mucoid layer is most closely apposed to the corneal epithelium and the lipid layer is at the tear film : air interface). Multiple disorders are associated with abnormal tear composition, quantity and/or quality, and secondary ocular surface changes.

4. Inflammation plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of dry eye.

II. The conjunctival epithelium rests on a connective tissue, the substantia propria.

III. The conjunctiva is divided into three zones: tarsal, fornical–orbital, and bulbar.

Congenital Anomalies

Cryptophthalmos (Ablepharon)

See Chapter 6.

Epitarsus

Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (Rendu–Osler–Weber Disease)

Ataxia–Telangiectasia (Louis–Bar Syndrome)

See Chapter 2.

Congenital Conjunctival Lymphedema (Milroy’s Disease, Nonne–Milroy–Meige Disease)

Dermoids, Epidermoids, and Dermolipomas

See later in this chapter and Chapter 14.

Laryngo-Onycho-Cutaneous (LOC or Shabbir) Syndrome

Vascular Disorders

Sickle-Cell Anemia

See Chapter 11.

Conjunctival Hemorrhage (Subconjunctival Hemorrhage)

I. Intraconjunctival hemorrhage (see Fig. 5.30) into the substantia propria, or hemorrhage between conjunctiva and episclera, most often occurs as an isolated finding without any obvious cause.

III. Histologically, blood is seen in the substantia propria of the conjunctiva.

Lymphangiectasia Hemorrhagica Conjunctivae

Ataxia–Telangiectasia

See Chapter 2.

Diabetes Mellitus

See section Conjunctiva and Cornea in Chapter 15.

Hemangioma and Lymphangioma

See also Chapter 14.

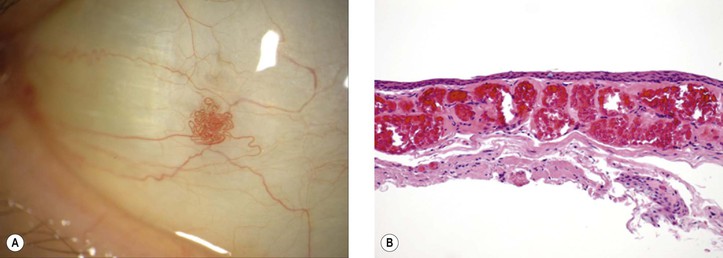

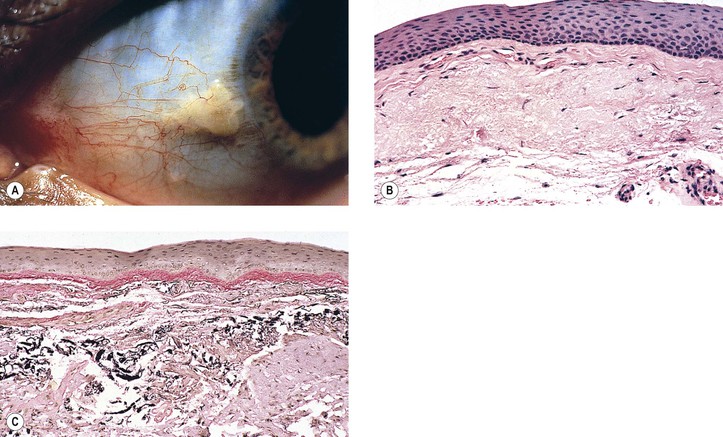

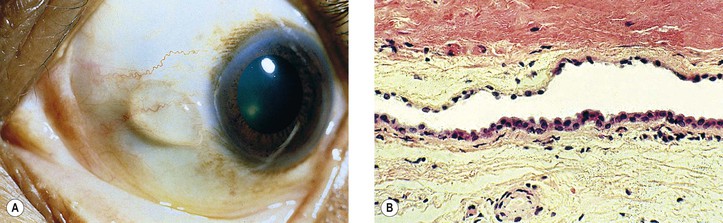

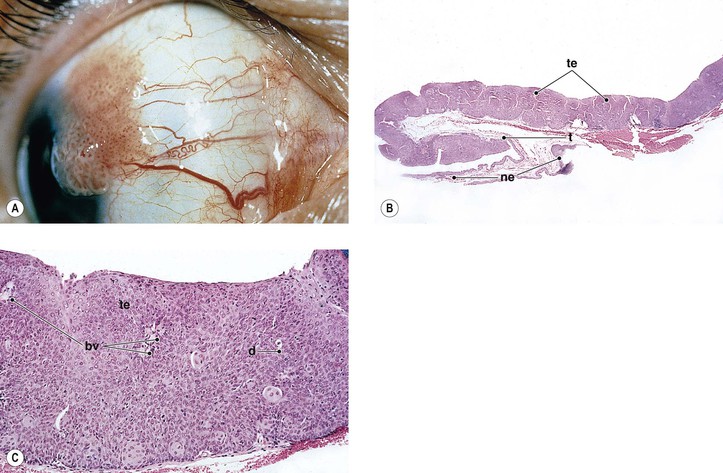

I. Acquired sessile hemangioma of the conjunctiva (Fig. 7.2)

A. Mean age at diagnosis is 58 years (range, 31–83 years); usually a coincidental finding.

B. Flat collection of intertwining, mildly dilated blood vessels usually on the bulbar conjunctiva.

D. Lesion is nonprogressive without systemic disease associations.

Inflammation

Basic Histologic Changes

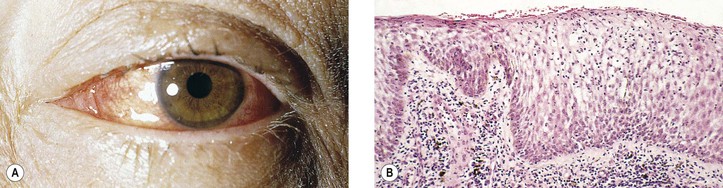

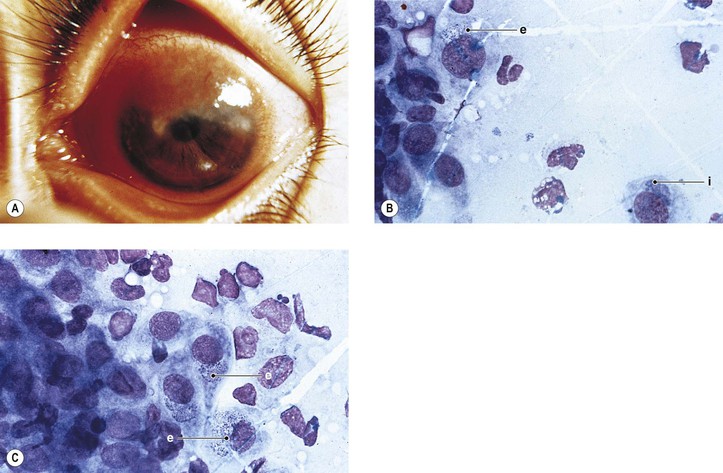

I. Acute conjunctivitis (Fig. 7.3)

A. Edema (chemosis), hyperemia, and cellular exudates are characteristic of acute conjunctivitis.

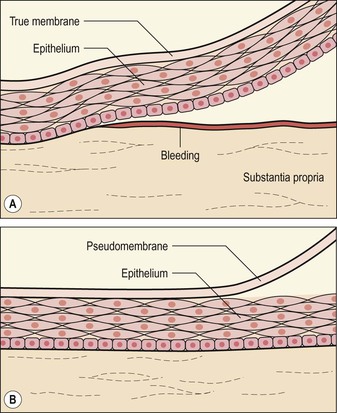

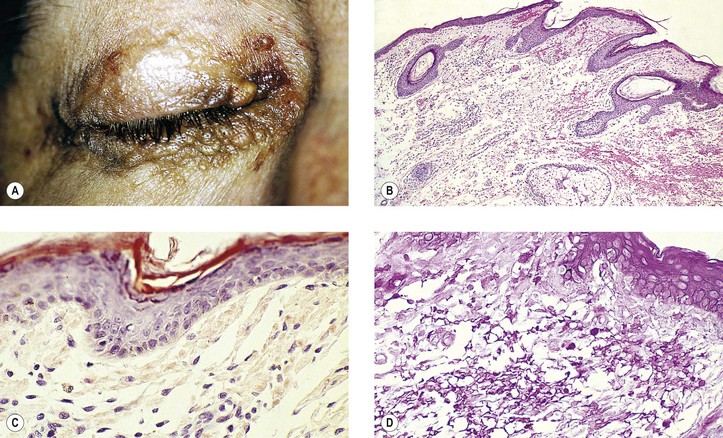

B. Inflammatory membranes (Fig. 7.4)

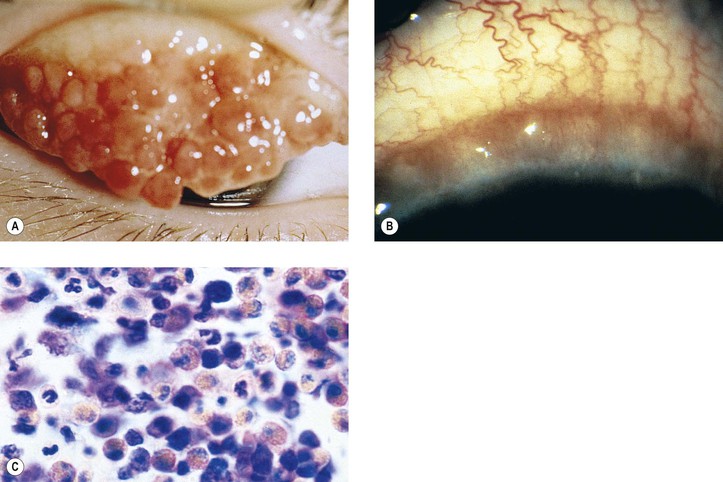

3. Ligneous conjunctivitis (Fig. 7.5) is an unusual bilateral, chronic, recurrent, membranous or pseudomembranous conjunctivitis of childhood, most commonly in girls, of unknown cause. The condition persists for months to years and may become massive.

c. Severe type I plasminogen deficiency has been linked to ligneous conjunctivitis.

II. Chronic conjunctivitis (Fig. 7.6)

A. The epithelium and its goblet cells increase in number (i.e., become hyperplastic).

B. The conjunctiva may undergo papillary hypertrophy (Fig. 7.7), which is caused by the conjunctiva being thrown into folds. Papillary hypertrophy is primarily a vascular response.

2. The lymphocyte (even lymphoid follicles) and plasma cell infiltrations are secondary.

C. The conjunctiva may undergo follicle formation. Follicular hypertrophy (Fig. 7.8) consists of lymphoid hyperplasia and secondary visualization.

E. Chronic inflammation during healing may cause an overexuberant amount of granulation tissue to be formed (i.e., granuloma pyogenicum; see Fig. 6.11).

F. The conjunctiva may be the site of granulomatous inflammation (e.g., sarcoid; see Chapter 4).

III. Ligneous conjunctivitis (see earlier, this chapter).

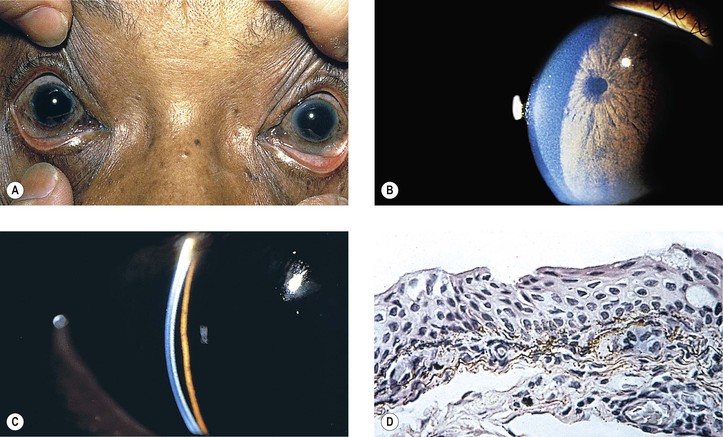

A. Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid (benign mucous membrane pemphigoid, pemphigus conjunctivae, chronic cicatrizing conjunctivitis, essential shrinkage of conjunctiva)

4. Histology

a. Subepithelial conjunctival bullae rupture and are replaced by fibrovascular tissue containing lymphocytes (especially T cells), dendritic (Langerhans’) cells, and plasma cells.

1) The epithelium has an immunoreactive deposition (immunoglobulin or complement) along its basement membrane zone. The presence of circulating antibodies to the epithelial basement membrane zone can also be helpful in making the diagnosis. Such immunohistochemical confirmation is important because the clinical characteristics of ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid and pseudopemphigoid are similar, which may lead to a clinical misdiagnosis.

Increased expression of connective tissue growth factor has been demonstrated in the conjunctiva of patients with ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, and it is probably one of the factors involved in the pathogenesis of the typical conjunctival fibrosis in the disorder. Macrophage colony-stimulating factor has increased expression in conjunctiva in ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, and there is a positive correlation between its expression and the accumulation of macrophages in conjunctival biopsies in patients with pemphigoid.

5) The histopathologic alterations in the ocular surface from abnormal tear film vary considerably depending on the nature of the precipitating ocular condition.

Specific Inflammations

Infectious

I. Virus—see subsection Chronic Nongranulomatous Inflammation in Chapter 1.

II. Bacteria—see sections Phases of Inflammation in Chapter 1 and Suppurative Endophthalmitis and Panophthalmitis in Chapter 3. Also see Chlamydiae below.

III. Chlamydiae cause trachoma, lymphogranuloma venereum, and ornithosis (psittacosis).

A. They are gram-negative, basophilic, coccoid, or spheroid bacteria.

3. Histology of MacCallan’s four stages:

a. Stage I: Early formation of conjunctival follicles, subepithelial conjunctival infiltrates, diffuse punctate keratitis, and early pannus

b. Stage II: Florid inflammation, mainly of the upper tarsal conjunctiva with the early formation of follicles appearing like sago grains, and then like papillae. The follicles cannot be differentiated histologically from lymphoid follicles secondary to other causes (e.g., allergic).

d. Stage IV: Arrest of the disease

D. Inclusion conjunctivitis (inclusion blennorrhea)

1. Inclusion conjunctivitis is caused by the bacterial agent C. trachomatis (oculogenitale).

E. Lymphogranuloma venereum (inguinale)

IV. Fungal—see the subsection Fungal, section Nontraumatic Infections in Chapter 4.

V. Parasitic—see the subsection Parasitic, section Nontraumatic Infections in Chapter 4 and see Chapter 8.

Noninfectious

I. Physical—see subsections Burns and Radiation Injuries (Electromagnetic) in Chapter 5.

II. Chemical—see subsection Chemical Injuries in Chapter 5.

III. Allergic

A. Allergic conjunctivitis is usually associated with a type 1 hypersensitivity reaction and can be subdivided into acute disorders (seasonal allergic conjunctivitis and perennial allergic conjunctivitis) and chronic diseases (vernal conjunctivitis, atopic keratoconjunctivitis, and giant papillary conjunctivitis).

Mast cells play a central role in the pathogenesis of ocular allergy. Their numbers are increased in all forms of allergic conjunctivitis, and they may participate in the process through their activation, resulting in the release of preformed and newly formed mediators. Chronic conjunctivitis may be accompanied by remodeling of the ocular surface tissues.

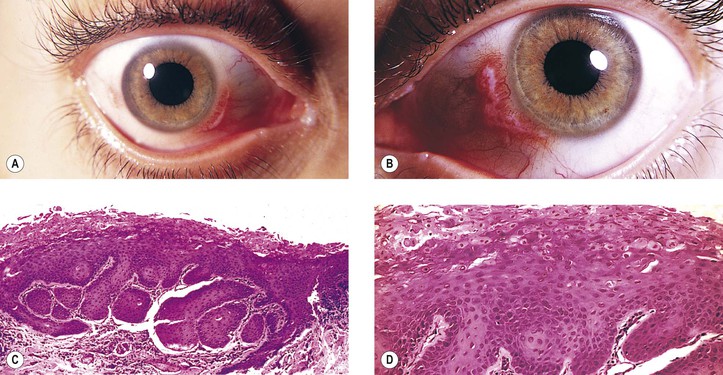

B. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis (vernal catarrh, spring catarrh; Fig. 7.10)

1. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis is a bilateral, recurrent, self-limited conjunctival disease occurring mainly in warm weather and affecting young people (mainly boys).

4. Histology

C. Inflammatory cells (eosinophils and neutrophils) in brush cytology specimens from the tarsus correlate with corneal damage in atopic keratoconjunctivitis. In atopic blepharoconjunctivitis, the tear content of group IIA phospholipase A2 is decreased without any dependence on the quantity of different conjunctival cells.

E. Contact blepharoconjunctivitis

F. Phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis

IV. Immunologic

A. Graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) conjunctivitis

2. It presents with pseudomembrane formation secondary to loss of the conjunctival epithelium.

3. In approximately 20% of these cases, the corneal epithelium also sloughs.

V. Neoplastic processes (e.g., sebaceous gland carcinoma) can cause a chronic nongranulomatous blepharoconjunctivitis with cancerous invasion of the epithelium and subepithelial tissues.

Injuries

See Chapter 5.

Conjunctival Manifestations of Systemic Disease

Deposition of Metabolic Products

I. Cystinosis (Lignac’s disease)—see Fig. 8.50.

II. Ochronosis—see Chapter 8.

III. Hypercalcemia—see Chapter 8.

IV. Addison’s disease: Melanin is deposited in the basal layer of the epithelium.

V. Mucopolysaccharidoses—see Chapter 8.

VI. Lipidosis—see Chapter 11.

VII. Dysproteinemias

VIII. Porphyria

IX. Jaundice

B. Rarely, the icterus can extend into the cornea.

X. Malignant atrophic papulosis (Degos’ syndrome)—see Chapter 6.

Deposition of Drug Derivatives

Vitamin A Deficiency: Bitot’s Spot

See Chapter 8.

Sjögren’s Syndrome

See Chapters 8 and 14.

Skin Diseases

Degenerations

Xerosis

I. Xerosis (dry eyes; Fig. 7.12) owing to conjunctival disease may result from keratoconjunctivitis sicca (Sjögren’s syndrome), ocular pemphigoid, trachoma, measles, vitamin A deficiency, proptosis with exposure, familial dysautonomia, chemical burns, and erythema multiforme (Stevens–Johnson syndrome).

Pterygium

See Chapter 8.

Pinguecula

I. Pinguecula (Fig. 7.13) is a localized, elevated, yellowish-white area near the limbus, usually found nasally and bilaterally, and seen predominantly in middle and late life.

II. Histologically, it appears identical to a pterygium except for lack of vascularization and corneal involvement.

Amyloidosis

I. Primary

Primary conjunctival amyloidosis should be considered in any patient with recurrent hyposphagma (conjunctival hemorrhage) of unknown cause.

A. Systemic (primary familial amyloidosis; see Fig. 12.10 and also Chapters 8 and 12)

1. Primary amyloidosis, now designated AL amyloidosis (AL amyloid is the same type of amyloid found in myeloma-associated amyloid), is regarded as part of the spectrum of plasma cell dyscrasias with an associated derangement in the synthesis of immunoglobulin.

2. Vitreous opacities are the most important ocular finding, but ecchymosis of lids, proptosis, ocular palsies, internal ophthalmoplegia, neuroparalytic keratitis, and glaucoma may result from amyloid deposition in tissues (see Chapter 12).

B. Familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy (see Chapter 12)

C. Localized (localized nodular amyloidosis; see also Chapter 8)

1. Small and large, brownish-red nodules may be found in the conjunctiva and lids.

2. The intraocular structures are not involved.

II. Secondary

A. Systemic (secondary amyloidosis)—the condition is not as common as primary local amyloidosis.

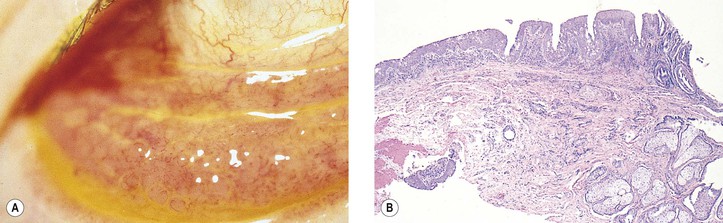

3. Secondary localized amyloidosis (Fig. 7.15) may result from such chronic local inflammations of the conjunctiva and lids as trachoma and chronic nongranulomatous, idiopathic conjunctivitis, and blepharitis.

III. Histology

1. Amyloid fibril proteins derived from immunoglobulin light chains are designated AL (see Chapter 12) and are found in primary familial amyloidosis and secondary amyloidosis associated with multiple myeloma and Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia (monoclonal gammopathies).

3. Another protein, protein AP, is found in all of the amyloidoses and may be bound to amyloid fibrils.

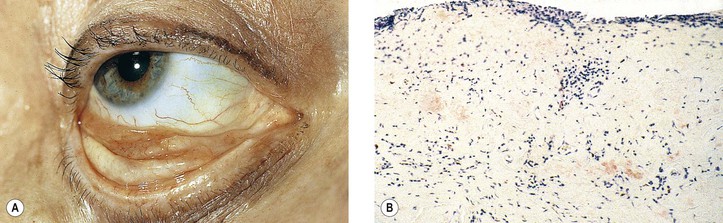

Conjunctivochalasis

I. Conjunctivochalasis is usually found in older individuals and consists of an elevation of the bulbar conjunctiva along the lateral or central lower-lid margin. It may also involve the upper bulbar conjunctiva.

A. It is a cause for tearing, and it may worsen dry-eye symptoms.

C. Inflammation plays an important role in severe conjunctivochalasis.

Cysts, Pseudoneoplasms, and Neoplasms

Choristomas

I. Epidermoid cyst—see Chapter 14.

II. Dermoid cyst—see Chapter 14.

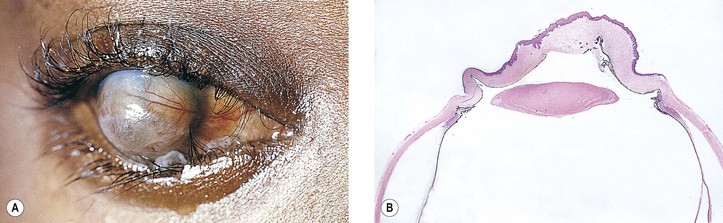

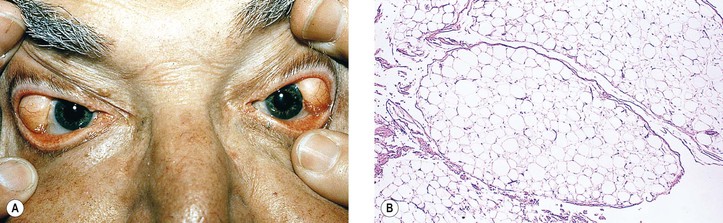

III. Dermolipoma (Fig. 7.16)

VI. Epibulbar (episcleral) osseous choristoma (bone-containing choristoma of the conjunctiva) is usually located in the supratemporal quadrant (see Fig. 8.65) and may contain other choristomatous tissue as frequently as 10% of the time. The lesion may be attached to the underlying muscle or sclera.

Hamartomas

Cysts

I. Cysts of the conjunctiva (Fig. 7.17) may be congenital or acquired, with the latter predominating.

III. Histologically, the structure depends on the type of cyst.

A. Epidermoid and dermoid cyst—see Chapter 14.

B. Epithelial inclusion cysts, lined by conjunctival epithelium, contain a clear fluid.

D. Inflammatory cysts contain polymorphonuclear leukocytes and cellular debris.

Pseudocancerous Lesions

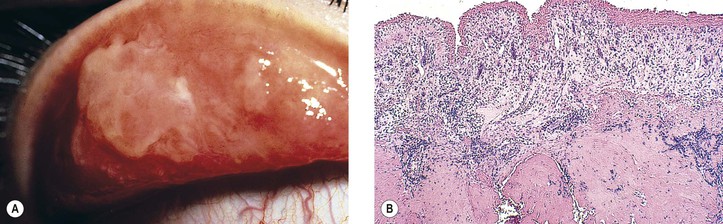

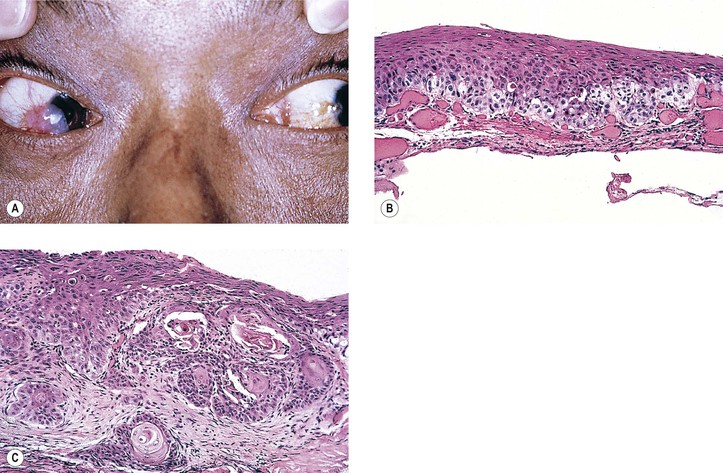

I. Hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis (HBID; Fig. 7.18; see Fig. 6.4A)

C. There is duplication in chromosome 4 (4q35).

D. Histologically, considerable acanthosis of the epithelium is present along with a chronic nongranulomatous inflammatory reaction and increased vascularization of the subepithelial tissue. A characteristic dyskeratosis, especially prominent in the superficial layers, is seen.

II. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (PEH; see Chapter 6)

A. PEH may mimic a neoplasm clinically and microscopically.

C. Keratoacanthoma (see Chapter 6) may be a specific variant of PEH, perhaps caused by a virus, or more likely a low-grade type of squamous cell carcinoma.

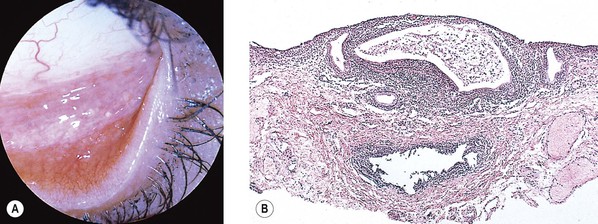

III. Papilloma (squamous papilloma; Fig. 7.19)

A. Conjunctival papillomas tend to be pedunculated when they arise at the lid margin or caruncle, but sessile with a broad base at the limbus.

1. Papillomas are rare in locations other than the lid margin, interpalpebral conjunctiva, or caruncle.

2. Approximately one-fourth of all the lesions of the caruncle are papillomas.

IV. Oncocytoma (eosinophilic cystadenoma, oxyphilic cell adenoma, apocrine cystadenoma; Fig. 7.20)

A. Oncocytoma is a rare tumor of the caruncle.

3. Rarely, the tumor may undergo carcinomatous transformation.

V. Myxoma

A. Myxomas are rare benign tumors that resemble primitive mesenchyme and are often mistaken for cysts.

1. They have a smooth, fleshy, gelatinous appearance and are slow-growing.

2. Myxomas may be found in Carney’s syndrome, an autosomal-dominantly inherited syndrome consisting of myxomas (especially cardiac but also eyelid), spotty mucocutaneous (including conjunctiva) pigmentation (see Chapter 17), and endocrine overactivity (especially Cushing’s syndrome).

B. Histologically, the tumor is hypocellular and composed of stellate and spindle-shaped cells, some of which have small intracytoplasmic and intranuclear vacuoles.

The stroma contains abundant mucoid material, sparse reticulin, and delicate collagen fibers.

VI. Dacryoadenoma

A. Dacryoadenoma is a rare benign conjunctival tumor arising from metaplasia of the surface epithelium.

VII. Rarely, inverted follicular keratosis may arise in the conjunctiva.

Potentially Precancerous Epithelial Lesions

Cancerous Epithelial Lesions

All such tumors may appear clinically as leukoplakia.1 Reported cases of neoplasms involving orbits containing ocular prostheses highlight the importance of a periodic thorough examination of such sockets.

I. In a review of 12,102 consecutive cases accessioned at an ocular pathology laboratory from 1993 to 2009, there were 273 (2.25%) conjunctival lesions, of which there were 86 (0.71%) epithelial tumors; 15 (17.4%) of the epithelial tumors were squamous cell papillomas. Among the ocular squamous neoplasia cases, 11.6% were actinic keratosis, 31.3% were conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia with variable degrees of atypia, 17.4% represented carcinoma in situ, and 19.7% were squamous cell carcinomas. Only one case of each basal cell carcinoma and mucoepidermoid carcinoma was found.

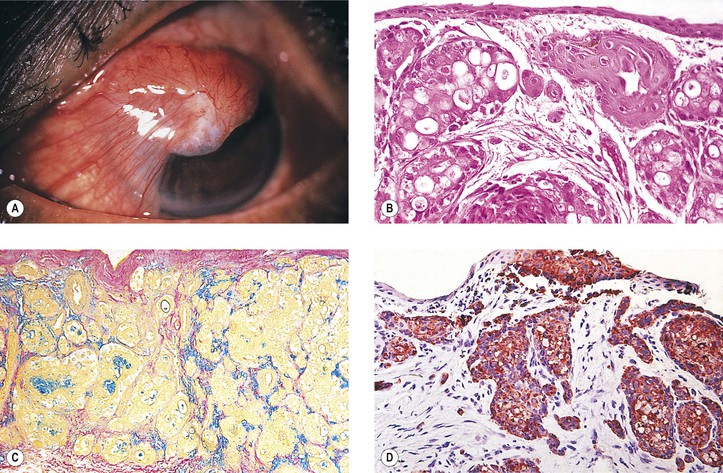

II. Carcinoma derived from the squamous cells of conjunctival epithelium

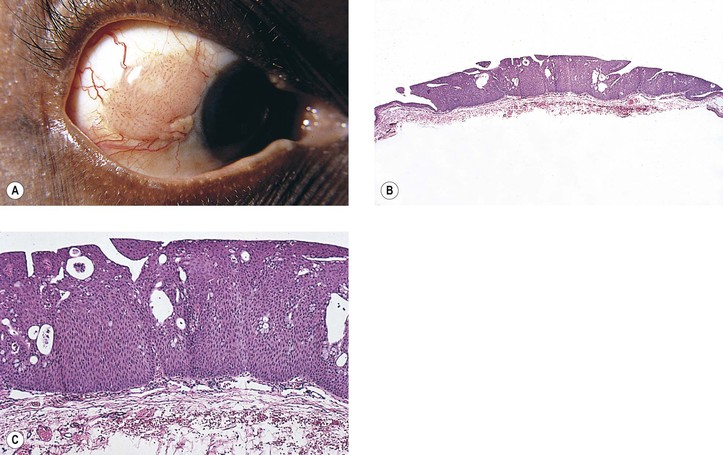

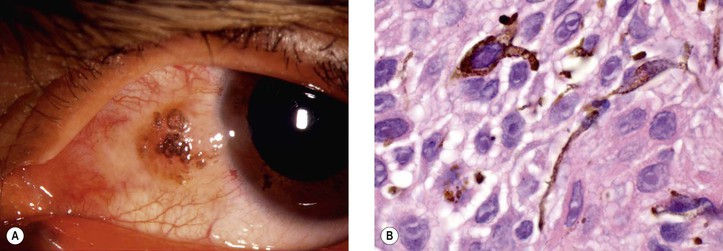

A. Conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasm (CIN; dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, intraepithelial carcinoma, intraepithelial epithelioma, Bowen’s disease, intraepithelioma; Figs. 7.21 and 7.22)

5. Histology

d. Polarity of the epithelium is lost, and mitotic figures commonly are found.

h. Regardless of patient race, pigmentation of conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma may occur (Fig. 7.23). Such pigmented lesions are uncommon, comprising 1.6% of lesions. Pigmented dendritic melanocytes are the source of the pigment, which may be “donated” to squamous cells, resulting in their having intracellular melanin in some cases.

B. Squamous cell carcinoma with superficial invasion (see Fig. 7.22B)

In addition to the epithelial changes of CIN, invasion by the malignant, pleomorphic, atypical squamous epithelial cells occurs through the epithelial basement membrane into the superficial subepithelial tissue.

C. Squamous cell carcinoma with deep invasion (see Fig. 7.22C)

In addition to the epithelial changes of CIN, there is invasion by the malignant squamous epithelial cells through the epithelial basement membrane deep into the subepithelial tissue or even into adjacent structures.

D. Squamous cell carcinoma with metastasis

All the features of squamous cell carcinoma with deep invasion are involved, plus evidence of metastasis. Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma may be an atypical presentation of HIV infection.

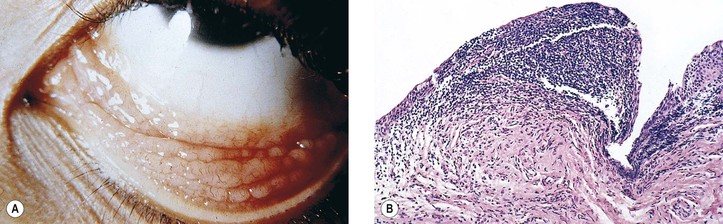

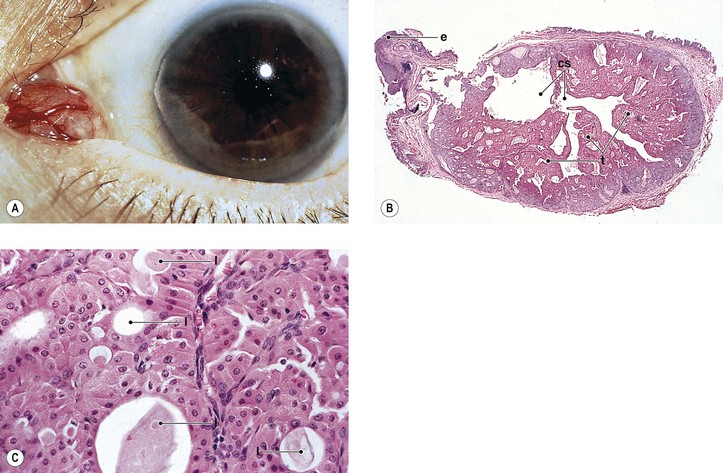

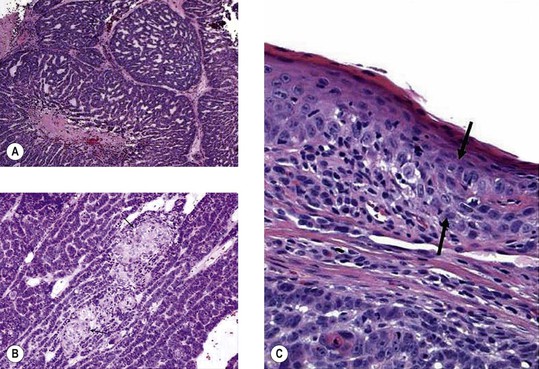

E. Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma (Fig. 7.24)

2. It is composed of small crowded cells with scant cytoplasm and hyperchromatic.

4. Cells have a nesting, lobular, and trabecular arrangement.

III. Carcinoma derived from the basal cells of conjunctival epithelium

Basal cell carcinoma rarely arises from the conjunctiva or caruncle.

IV. Carcinoma derived from the mucus-secreting cells and squamous cells of conjunctival epithelium

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma (Fig. 7.25) is a rare conjunctival tumor characteristically composed of mucus-secreting cells intermixed with epidermoid (squamous) cells.

C. Histologically, lobules of tumor cells show a variable admixture of epidermoid and mucus-secreting cells.

Histochemical stains for mucin are most helpful in confirming the diagnosis.

Pigmented Lesions of the Conjunctiva

See section Melanotic Tumors of Conjunctiva in Chapter 17.

Laugier–Hunziker syndrome is a rare acquired hyperpigmentation of the oral mucosa and lips, which is often associated with longitudinal melanonychia (black pigmentation of the nails). It may also be associated with conjunctival and penile pigmentation. Histopathologic examination demonstrates basal epithelial melanosis, moderate acanthosis, and superficial pigmentary incontinence. Electron microscopic examination reveals increased number of normal-appearing melanosomes inside basal keratinocytes and dermal melanophages.

Stromal Neoplasms

I. Angiomatous—see discussions of hamartomas and vascular mesenchymal tumors in Chapter 14.

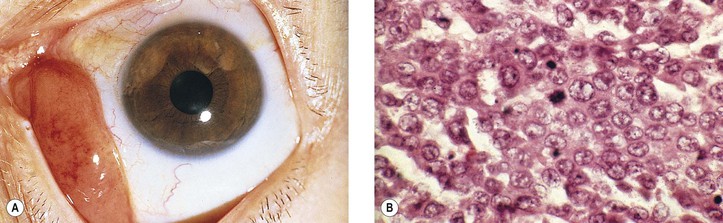

II. Pseudotumors, lymphoid hyperplasia, lymphomas, and leukemias (Fig. 7.26)—see discussions of tumors of the reticuloendothelial system, lymphatic system, and myeloid system in Chapter 14.

B. Extranodal marginal-zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) constitutes approximately 88% of all lymphomas involving the ocular adnexa and tends to appear in patients with a history of autoimmune disease or chronic inflammatory disorders (it has been reported in a child).

6. Uncommonly, conjunctival B-cell lymphoma may present as an ulcerating tarsal conjunctival mass.

III. Juvenile xanthogranulomas—see Chapter 9.

IV. Neural tumors—see discussion of neural mesenchymal tumors in Chapter 14.

V. Fibrous tumors—see discussion of fibrous–histiocytic mesenchymal tumors in Chapter 14.

VI. Leiomyosarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma—see discussion of muscle mesenchymal tumors in Chapter 14.

A. Rarely, rhabdomyosarcoma may present as a conjunctival lesion without orbital extension.

VII. Metastatic

Access the complete reference list online at ![]()