Chapter 51 Congenital disorders of the pancreas

Surgical considerations

Embryologic Development of the Pancreas

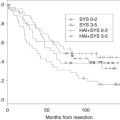

The basis for the understanding of congenital abnormalities of the pancreas is the embryologic development of the organ (see Chapter 1A). The pancreas develops from two buds originating from the endodermal lining of the duodenum. The dorsal bud forms posteriorly within the mesentery, whereas the ventral bud is associated with the hepaticopancreatic duct (Fig. 51.1). During the second month of development, the stomach rotates and the duodenum becomes C-shaped. As part of this process, the ventral pancreatic bud migrates dorsally, coming to lie posteroinferiorly to the dorsal bud, forming what will become the inferior head/uncinate process of the pancreas. In the majority of individuals, the main pancreatic duct (of Wirsung) is formed by the entire ventral duct, and the distal dorsal duct and enters the duodenum at the major papilla. The persistence of the proximal part of the dorsal duct occurs in approximately 25% and results in an accessory duct (of Santorini), which enters the duodenum by the minor papilla (see Fig. 51.1) (Rösch et al, 1976). There is no known pathologic consequence of this normal variation. A failure of fusion of the ductal system occurs in roughly 10% of the normal population (Dawson & Langman, 1961; Millbourn, 1959), resulting in the entire dorsal pancreas—superior head, body, and tail—draining through the minor papilla and ventral pancreas, the inferior head and uncinate process, and finally through the major papilla (Fig. 51.2). This abnormality is termed pancreas divisum and is described in more detail below.

FIGURE 51.1 Embryologic development of the pancreas.

(Netter illustration from http://www.netterimages.com. Copyright Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved.)

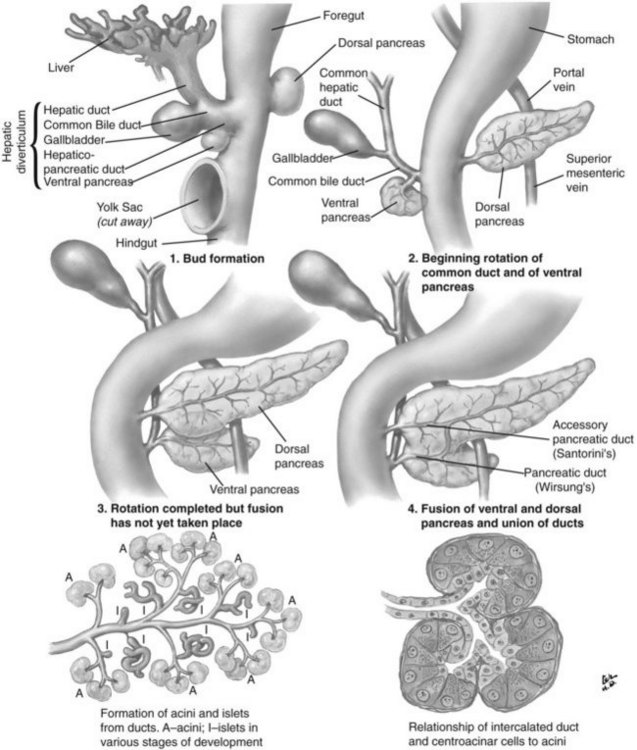

FIGURE 51.2 Pancreas divisum describes the incomplete fusion of the dorsal and ventral pancreatic ducts.

A number of studies published recently have identified mechanisms by which the pancreas is specified from the early endoderm (Kumar & Melton, 2003). Retinoic acid and bone morphogenic peptide both appear to have important roles in defining early endodermal compartments in the embryo (Stafford & Prince, 2002; Tiso et al, 2002). The origins of the signaling mechanisms involved in the specification of the dorsal and ventral pancreas are different. In the dorsal pancreas, signals arising from the notochord (Kim et al, 1997) and dorsal aorta (Lammert et al, 2001) are required; in the ventral pancreas, the lateral plate mesoderm is important (Kumar et al, 2003). The specific identity of these signals has not yet been established, although the Hedgehog family of signaling molecules appears to be significant (Kim & MacDonald, 2002).

Pancreas Divisum

Pancreas divisum (PD) results from incomplete fusion of the dorsal and ventral pancreatic ducts toward the end of the second month of embryogenesis. The distal dorsal pancreatic duct typically fuses with the ventral pancreatic duct to drain the entire pancreas into the duodenum via the major papilla (see Chapter 1B). The proximal dorsal duct can persist as an accessory pancreatic duct and may drain via the minor papilla. Complete PD exists when there is no communication between the dorsal and ventral systems and the majority of the pancreas drains via the dorsal duct through the minor papilla (see Fig. 51.2). Variations exist where a small branch may connect the two ducts, termed incomplete pancreas divisum.

Recent investigations have suggested that PD may be explained by distinct patterns of incomplete fusion of branches of the dorsal and ventral pancreatic ducts (Kamisawa et al, 2007a), confirming theories first proposed in early anatomic studies (Dawson & Langman, 1961). The first description of PD is from 1865, attributed to Josef Hyrtl (1810-1894), professor of anatomy at the Universities of Prague and Vienna. However, as discussed by Stern (1986), a number of anatomists were aware of it much earlier than this, including Regnier de Graaf, who described the finding in 1664.

In postmortem studies performed throughout the twentieth century, the prevalence of PD is reported to be approximately 8% (range, 4% to 14.5%) (Baldwin, 1911; Berman et al, 1960; Birnstingl, 1959; Cameron, 1924; Charpy, 1898; Dawson & Langman, 1961; Fogel et al, 2007; Clairmont & Hadjipetros, 1920; Hand, 1963; Helly, 1898; Hjorth, 1947; Keyl, 1925: Kleitsch, 1955; Mehnen, 1938; Millbourn, 1959; Naatanen, 1941; Opie, 1903; Rienhoff, 1945; Schirmer, 1893; Schmieden & Sebening, 1927; Schwarz, 1926; Sigfusson et al, 1983; Smanio, 1969; Stimec et al, 1996). With the development of endoscopic retrograde pancreatography (ERCP) in the late 1960s, however, the considerable congenital variation in the ductal system of the pancreas became more widely appreciated (Cotton, 1972; McCune et al, 1968). The prevalence of PD is lower in published ERCP series than in anatomic series for reasons that are not clear, although it may be due to referral bias, difficulty in the interpretation of pancreatograms, or inability to cannulate the minor papilla. The reported prevalence is particularly low in Japanese series (0.3% to 0.6%) compared with Western populations (approximately 5%; Cotton, 1980).

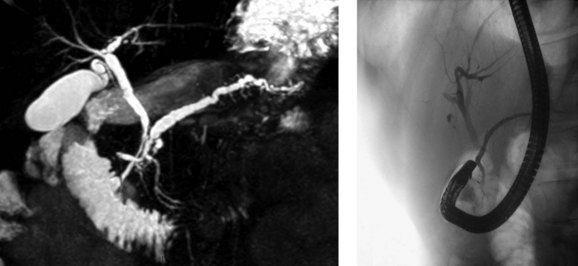

PD is clinically relevant from three main points of view (Fogel et al, 2007). First, the small ventral duct seen in PD must be differentiated from a similar appearance seen in some cases of pancreatic cancer. Second, on cannulating the major papilla at ERCP, only the ventral portion of the pancreas may be visualized in PD, which risks missing important pathology if a pancreatogram is not performed via the minor papilla (see Chapter 18). Third, PD may be associated with disease, such as pancreatitis (see Chapter 53). With regard to the first point, it is important for those performing ERCP to be aware of the anomaly to become proficient in interpreting pancreatograms (Fig. 51.3). Other forms of imaging, such as computed tomography (CT), must be used if there is uncertainty whether a mass lesion is present and causing a ductal abnormality. In relation to the second point, it is important to become proficient at cannulation of the minor papilla, which is considerably more challenging than cannulating the major papilla (see Chapter 18). It commonly sits in a superior, more ventral position. Cannulation may be facilitated by having the duodenoscope in the “long position” and by administration of intravenous secretin (O’Connor & Lehman, 1985). The third point is discussed in detail below.

Possible Association Between Pancreas Divisum and Pancreatitis

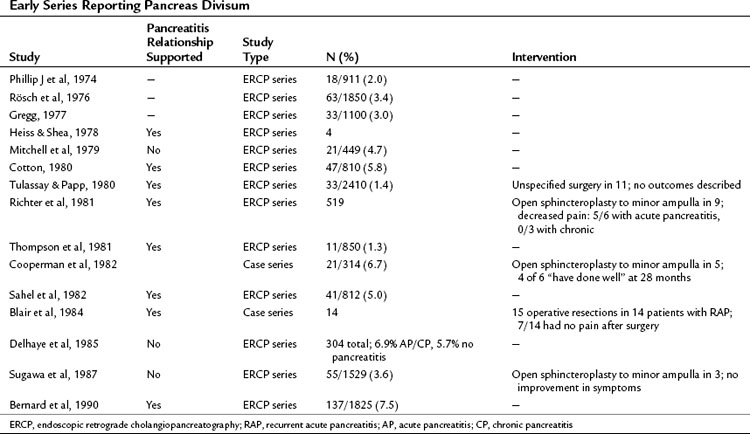

The question of whether PD causes recurrent acute pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis, or pancreas-related pain has been debated for many years (Table 51.1). Those proposing the theory suggest that obstruction occurs at the level of the minor papilla, the caliber of which is too narrow to drain the majority of the pancreas. This is supported by an early study reporting an elevated pressure in the dorsal duct (23.7 ± 1.3 mm Hg) compared with the ventral duct (10.8 ± 1.9 mm Hg) in six patients with PD, whereas pressures were similar when two ducts existed in patients without PD (Staritz & Meyer zum Buschenfelde, 1988). This was contradicted in a subsequent study in which no difference in duct pressures was observed between the major and minor papillae in four patients with recurrent acute pancreatitis and PD (Satterfield et al, 1988). Another early report demonstrated chronic pancreatitis confined to the dorsal pancreas in two pancreatoduodenectomy specimens from patients with PD who had resections for symptom control (Blair et al, 1984).

Difficulty exists in demonstrating an epidemiologic relationship between PD and pancreatitis because early anatomic studies were small and confounded by different definitions, and ERCP series are skewed by selection bias (Blair et al, 1984). In the largest early series of 1850 successful major ampulla cannulations, Rösch and colleagues (1976) identified PD in 63 cases (3.4%). The indications for pancreatography were not given, but pathologic findings were seen in 13 of 63 patients with PD; changes were consistent with pancreatitis in 12 and tumor in one. In the next large series by Gregg (1977), 33 patients with PD were identified among 1100 patients referred primarily for investigation of pancreatic-type pain or pancreatitis. Documented pancreatitis was present in 15 patients, and another 11 had recurrent episodes of pain typical of pancreatitis.

These and similar studies have been used as evidence of a link between PD and pancreatitis, but the absence of a suitable control group makes the assertion weak. Mitchell and colleagues (1979) identified this problem and performed a retrospective analysis of patients who had undergone ERCP and observed that 21 (4.7%) of 449 patients had PD, whereas 4 (3.3%) of 120 patients with pancreatitis defined by clinical and/or ERCP criteria had PD. Thus in this series the prevalence of PD in patients with pancreatitis was the same as the prevalence of PD in the series as a whole. This has been supported by the largest published ERCP series of 304 patients, in which the dorsal duct was visualized in 97 patients (Delhaye et al, 1985). The frequency of PD was similar in patients with acute or chronic pancreatitis (6.9%) as in all patients in the series undergoing ERCP (5.7%).

Contrary to these findings, Cotton reported that in patients with primary biliary disease who had an incidental pancreatogram at the time of endoscopic cholangiogram, the prevalence of PD was 3.6% (Cotton, 1980). This was compared with a prevalence of 16.4% in those with chronic or recurrent acute pancreatitis. In 83 patients with idiopathic pancreatitis, recurrent pancreatitis with no clear etiology such as gallstones, alcohol, or trauma—the prevalence of PD was 25.6%.

Imaging in Pancreas Divisum

One of the difficulties in relating PD to pancreatitis is the inconsistency in making the diagnosis. ERCP studies of patients without pancreatitis consistently report a lower prevalence of PD when compared with MRCP or postmortem studies (Table 51.2). The use of secretin during MRCP (S-MRCP) improves the detection rate of PD (Manfredi et al, 2000), yet it is still reported to be missed on S-MRCP, possibly because of suboptimal magnetic resonance techniques or inexperience in those reporting the MRCP (see Chapter 17; Carnes et al, 2008). Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) as an alternative imaging modality has gained in popularity and is reported to be useful in the investigation of patients with acute recurrent pancreatitis of unknown etiology (see Chapter 14; Petrone et al, 2008). A recent study reported the use of portal venous phase 64 multirow detector CT. Five of 93 patients had PD diagnosed on MRCP or ERCP. Of these, one observer detected three cases and a second observer found four cases by reviewing the MDCT images (Anderson & Soto, 2009). ERCP features of the minor papilla that suggest the presence of PD include an enlarged papilla or open orifice and are believed to moderately predict the presence of PD; however, a significant number of patients with PD do not have these features (Alazmi et al, 2007; Lawrence et al, 2009).

Table 51.2 Prevalence of PD in Patients Without Pancreatitis by Method of Investigation or Imaging Modality

| Investigation Type | N | % Prevalence of PD (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Postmortem | 2895 | 7.8 (6.8-8.8) |

| MRCP | 505 | 9.3 (6.8-11.8) |

| S-MRCP | 156 | 17.9 (11.9-24.0) |

| ERCP | 16,078 | 4.1 (3.8-4.4) |

PD, Pancreatis divisum; MRCP, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; S-MRCP, secretin-enhanced MRCP; ERCP, Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; CI, confidence interval

From Fogel EL, et al, 2007: Does endoscopic therapy favorably affect the outcome of patients who have recurrent acute pancreatitis and pancreas divisum? Pancreas 34:21-45.

Therapy to the Minor Papilla in Those with Pancreas Divisum and Pancreatitis

If PD is associated with obstruction at the minor papilla, which in turn contributes to the occurrence of pancreatitis and pancreatic pain, then it follows that surgical intervention to relieve this obstruction would be beneficial. As has been discussed, significant controversy exists as to whether this assumption is correct or not. A number of studies have been performed examining whether therapy to the minor papilla is beneficial in patients with acute recurrent pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis, or pancreas-related pain; however, little in the way of randomized controlled data has been generated (Table 51.3; see Chapter 53, Chapter 55A, Chapter 55B ). Interventions examined include endoscopic dilation, papillotomy, and sphincterotomy of the minor papilla, with or without stent placement, and surgical sphincteroplasty.

The first minor papilla endoscopic sphincterotomy was described by Cotton in 1978, and the majority of publications since have been small case series with short follow-up times. Lehman and colleagues (1993) described the effects of minor papilla sphincterotomy in 52 PD patients with chronic pancreatic pain (n = 24), recurrent acute pancreatitis (n = 17), or chronic pancreatitis (n = 11) with longstanding symptoms refractory to conservative management. Minor papilla sphincterotomy was performed with a needle knife over a previously placed dorsal pancreatic duct stent, with a mean follow-up of 1.7 years. When compared with the chronic pain and chronic pancreatitis groups, patients with recurrent acute pancreatitis had a significant reduction in mean symptom score (recurrent acute pancreatitis, 76.5%; chronic pancreatitis, 27.3%; chronic pain, 26.1%) and inpatient hospital stay. This reflects other published results that consistently show less benefit after minor papilla therapy in those with chronic pancreatitis or chronic pain compared with those with recurrent acute pancreatitis. Complications were seen in 15%, and one patient died of a pancreatic abscess after a failed cannulation. Of concern, 50% of patients evaluated at the time of stent removal had stent-induced dorsal duct changes.

In a prospective, randomized, controlled trial published by Lans and colleagues (1992), 19 patients with PD and recurrent acute pancreatitis—two or more episodes of abdominal pain associated with a rise in amylase greater than twice the upper limit of normal—and no other identified etiology were recruited. Ten patients were randomized to stent placement, and nine were randomized to no treatment, with follow-up for 1 year. In the stent group, no patients subsequently came to the hospital with pain, but five patients in the control group were admitted, and two more came in with pain. Furthermore, nine patients in the stent group rated their pain improved by 50% or more, but only one patient in the control group reported a similar improvement.

It has been pointed out that a significant period of time can exist between attacks of pancreatitis in this patient group, and this study has since been criticized on the basis of the short duration of follow-up. Sherman and colleagues (1994) have also published randomized data in abstract form in which patients with chronic abdominal pain thought to be pancreatic in origin and PD were randomized to minor papilla sphincterotomy (n = 16) or no intervention (n = 17). Mean follow-up time in the treated and untreated groups was 2.1 and 1.2 years, respectively. Although an improvement in pain was seen in 43.8% of treated patients compared with 23.5% in the control group, this trend did not reach statistical significance.

Borak and colleagues (2009) published the long-term outcomes after endoscopic minor papilla therapy in 145 patients with PD over a 6-year period. Follow-up data were available for 113 patients (78%), and the median follow-up time was 43 months. The majority of patients had a needle-knife sphincterotomy (82%) and temporary stent placement (90%). Primary success, defined as the patient being better or cured after a single ERCP session, was seen in 53.2% of patients with recurrent acute pancreatitis, 18.2% of those with chronic pancreatitis, and 41.4% of those with chronic/recurrent epigastric pain. Two or more ERCP sessions were required in 41.6%, with success in 71% of patients with recurrent acute pancreatitis, 46% of those with chronic pancreatitis, and 55% of those with chronic, recurrent epigastric pain. In a multivariate analysis that corrected for age, sex, symptom frequency/duration, and length of follow-up, chronic pancreatitis and younger age both independently predicted failure of improvement after treatment. Complications occurred in 13% after ERCP, including mild and moderate pancreatitis, mild bleeding, and anesthetic complications.

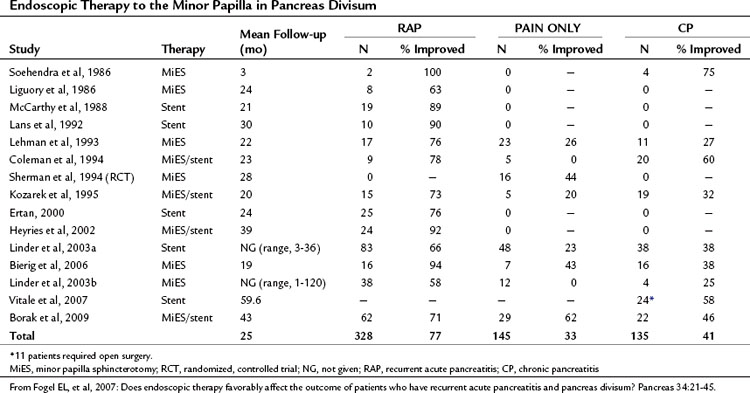

Surgical sphincteroplasty to the minor papilla, usually combined with cholecystectomy and major papilla sphincteroplasty, has been used in the treatment of recurrent acute pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis, and chronic pancreatic-type pain associated with PD (Table 51.4). In the largest published series by Warshaw and colleagues (1990), 88 patients with recurrent acute pancreatitis (49%) or “pancreatic pain” (51%) had minor papilla sphincteroplasty with a mean follow-up of 53 months; 70% of patients were reported to show improvement, 85% if the minor papilla was stenotic at surgery, compared with 27% if it was not (P < .01). Of those with recurrent acute pancreatitis, 82% were reported to have improved compared with 56% in the chronic pain group (P < .01). Preoperative ultrasonography (US) with secretin stimulation was compared with examination of the minor papilla and had a sensitivity of 78% and a specificity of 97%. Thus preoperative US with secretin stimulation was judged to be a good predictor of surgical success (92% success if positive, 40% success if negative). Seven patients were documented to have developed a restenosis at the minor papilla, six of whom had further surgery. The study concluded that a demonstrable stenosis at the minor papilla was a necessary cofactor in the development of recurrent acute pancreatitis or pancreatic pain in patients with PD.

Surgical sphincteroplasty is not without risk, however. In a recent large series of 446 patients, complications were reported in 34.8% of patients; pancreatitis (8.8%), asymptomatic hyperamylasemia (6.0%), and wound/abdominal infection (7.1%) were the most common morbidities. One death occurred after a duodenal leak (Madura et al, 2005).

The Case Against an Association Between Pancreas Divisum and Pancreatitis

An argument is also made against the theory of minor papilla obstruction. It is argued that patients with pancreatitis secondary to PD should have a dilated ductal system, but this has not been shown to be the case in the majority of studies that have assessed for it (Fogel et al, 2007). Similarly, if pancreatitis were associated with PD, only the dorsal pancreas should be affected, yet ventral duct pancreatitis is present in up to 11.8% of patients with PD and is the only duct involved in 4.2% of patients.

Cystic Fibrosis and Recurrent Pancreatitis

Cohn and colleagues (1998) and Sharer and colleagues (1998) first described the link between cystic fibrosis gene mutations and idiopathic pancreatitis. More recently, Choudari and colleagues (2004) demonstrated that mutations of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene were present in 8 (22%) of 37 patients with PD and pancreatitis compared with 0 of 20 patients with PD and no history of pancreatitis (odds ratio [OR], 11.8; confidence interval [CI], 8.9 to 14.7; P = .02). The authors concluded that in patients with PD, CFTR mutations increased the risk for pancreatitis. Furthermore, Gelrud and colleagues directly measured CFTR gene function in nasal epithelium in response to isoproterenol and demonstrated that those with PD and recurrent acute pancreatitis had results somewhere between those observed for healthy controls and those for classic cystic fibrosis patients. Thus CFTR dysfunction may explain why some PD patients have recurrent acute pancreatitis but others with PD do not. Moreover, of 12 patients with PD and recurrent acute pancreatitis, 10 had undergone therapy to the minor papilla, and only 2 had resolution of their symptoms.

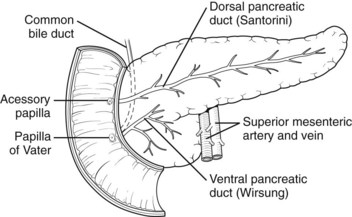

Annular Pancreas

Annular pancreas is a rare congenital abnormality in which the head of the pancreas completely encircles the second part of the duodenum (Fig. 51.4). It was first described in 1862 by Ecker, who reported a “ring derived from the head of the pancreas which surrounded the descending portion of the duodenum and was formed by uninterrupted glandular tissue” (Ravitch & Woods, 1950). The prevalence in autopsy studies is approximately 3 in 20,000 (Ravitch & Woods, 1950) but is higher in patients undergoing ERCP, at approximately 3 in 1000 (Fogel et al, 2006). Given the difficulty in making the diagnosis during autopsy and the highly selected patient population undergoing ERCP, the true prevalence likely lies somewhere in between.

FIGURE 51.4 Development of annular pancreas.

(Modified from Zyromski, et al, 2008: Annular pancreas: dramatic differences between children and adults. J Am Coll Surg 206:1019-1025.)

Pathogenesis

In early development, the ventral pancreas is formed by two buds (see Chapter 1A). In mammals, the left ventral pancreatic bud is thought to regress (Lammert et al, 2001; Odgers, 1930), and the larger right ventral pancreatic bud migrates to take up the position seen in the adult. A number of hypotheses have been proposed to explain the occurrence of annular pancreas. The most persistent is that of Lecco (1910), who suggested that adherence of the right ventral pancreatic bud to the duodenum before gut rotation resulted in a partial or complete ring of pancreatic tissue around the duodenum. A competing hypothesis offered by Baldwin (1910) postulates that the left ventral bud persists to form the annulus. Although in most annular pancreas specimens, only one ventral lobe is apparent, reports of a bilobar ventral pancreas have surfaced that support Baldwin’s theory (Nobukawa et al, 2000). Neither of these theories explains the variation in the position of the annular duct seen in various specimens, and Kamisawa and colleagues (2001) proposed a new theory that the tip of the left ventral bud adheres to the duodenum and stretches to form a ring. The exact location of this attachment in relation to the bile duct determines the final arrangement of the annular duct.

Reports of familial annular pancreas support a genetic basis for the disease. Annular pancreas has been described in siblings (Claviez et al, 1995; Lainakis et al, 2005; Montgomery et al, 1971), a mother and three of her children (Jackson & Apostolides, 1978), a mother and son (MacFadyen & Young, 1987), a mother and daughter (Hendricks & Sybert, 1991; Rogers et al, 1993), and a father and son (Mitchell et al, 1993), and a recent report describes the anomaly in monozygotic twins (Hulvat et al, 2006).

Clues as to the genetic basis of the disease are beginning to emerge. Only recently has it been shown that the cells that form the annulus are derived entirely from the ventral pancreas (Jarikji et al, 2009). In the same report, it was demonstrated that in Xenopus embryos, inactivation of transmembrane 4 superfamily member 3 (TM4SF3), a member of the tetraspanin family, inhibited fusion of the dorsal and ventral pancreatic buds. Overexpression of the same gene promoted development of annular pancreas. This would suggest that the product of this gene directly regulates the migration of ventral pancreatic bud cells, although whether it plays a role in the formation of annular pancreas in humans remains to be seen.

Another recent study has demonstrated a link between the Hedgehog signaling pathway and the development of annular pancreas. Members of the Hedgehog family of genes promote growth and differentiation of organs, and defects are associated with congenital malformations of the foregut (Litingtung et al, 1998). In 42% of mice embryos with a targeted inactivation of the Indian Hedgehog (IHH) gene, a member of the mammalian Hedgehog family, changes in the morphology of the ventral pancreatic bud similar to annular pancreas were seen (Hebrok et al, 2000). In most, the annulus was complete, although pancreas cells were not seen within the muscularis of the duodenum, as has been described in humans. Annular pancreas is also frequently seen after inactivation of Sonic Hedgehog (SHH), although the incidence of the anomaly is closely related to the background strain of the transgenic mouse, suggesting interaction with other genetic modifiers (Ramalho-Santos et al, 2000). SHH is not expressed in pancreatic tissue; therefore it has been suggested that a defect in duodenal Hedgehog signaling may lead to the anomaly because both SHH and IHH are expressed in the developing gut (Bitgood & McMahon, 1995; Hebrok et al, 2000). SHH knockout mice embryos also demonstrate a number of other abnormalities, including gut malrotation (100%), intestinal transformation of the stomach (100%), duodenal stenosis (67%), and imperforate anus (100%), strikingly similar to congenital malformations seen in humans with annular pancreas (see below).

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis in Adults

An estimated one half to two thirds of cases of annular pancreas in adults remain asymptomatic (Sandrasegaran et al, 2009). Annular pancreas presents with equal frequency in adults and children; in a recent series of 103 patients with annular pancreas, 55 (53.4%) were seen as adults (median age, 47 years), and 48 (46.6%) were seen as children (median age, 1 day) (Zyromski et al, 2008). Of those seen as adults, 41 (75%) were seen with pain, and 12 (22%) were diagnosed with pancreatitis; only 13 (24%) had gastrointestinal symptoms that included vomiting, and 6 (11%) had obstructive jaundice and/or abnormal liver function test results. In addition, 16 patients (29%) were also found to have PD, a higher prevalence than is seen in the general population (see previous section), which may suggest that similar genetic abnormalities link the two conditions. The diagnosis of annular pancreas was made by ERCP in 26 patients (47%), by abdominal CT in 10 patients (18%), by MRCP in 9 patients (16%), and at operation in 7 patients (13%; Fig. 51.5) (Zyromski et al, 2008).

In a recent ERCP series, 26 (93%) of 28 patients with annular pancreas without previous bypass were noted to have duodenal narrowing but no retained gastric contents (Fogel et al, 2006). Pancreatography was attempted in 32 patients and was successful in 30 (94%). Improvements in imaging have led to the identification of incomplete annular pancreas, in which the annulus does not fully encircle the duodenum (Sandrasegaran et al, 2009). The presence of pancreatic tissue on cross-sectional imaging posterolateral to the second part of the duodenum has a high sensitivity (92%) and specificity (100%) for this. Three (33%) of nine patients found to have incomplete annular pancreas on imaging had gastric outlet obstruction (Sandrasegaran et al, 2009).

A number of case reports describe annular pancreatitis in association with neoplasm, most commonly periampullary or pancreatic malignancy, raising the question as to whether annular pancreas predisposes to neoplasia (Ben-David et al, 2004; Benger & Thompson, 1997; Foo et al, 2007; Kamisawa et al, 1995; Shan et al, 2002; Yasui et al, 1995). The adult population in whom annular pancreas is diagnosed is a highly select group with a variety of symptoms. The incidence of annular pancreas is too small to be certain, but it is likely that the association is a result of bias rather than pathogenesis. What should be remembered is that the symptoms of a patient diagnosed with annular pancreas are not necessarily secondary to the annular pancreas; a second condition may be present. For instance, annular pancreas rarely presents with obstructive jaundice; therefore, when a patient with obstructive jaundice is found to have annular pancreas, a high index of suspicion for an underlying malignancy must be maintained.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis in Children

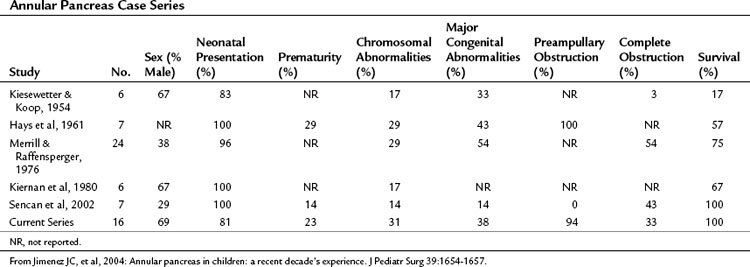

A significant difference between the adult and pediatric populations with annular pancreas is the prevalence of associated congenital abnormalities in children. The majority of children with annular pancreas show evidence of the condition in the first days after birth: in a recent series of 16 patients, 12 (75%) came to medical attention during the first week of life, one during the first month, and the remainder within the first year (Table 51.5) (Jimenez et al, 2004). If complete duodenal obstruction is present, polyhydramnios will usually be a feature; primary biliary obstruction and jaundice are not typical (Merrill & Raffensperger, 1976).

Preampullary obstruction resulting in nonbilious vomiting has been reported to be more common in annular pancreas than in other causes of duodenal obstruction (94% vs. 10%; Hays et al, 1961; Jimenez et al, 2004). In the series by Zyromski and colleagues (2008), 27 (56%) of 48 children with annular pancreas were suspected to have the condition based on prenatal US, and the remainder were seen with gastrointestinal obstruction, 37 (77%) of whom were diagnosed within the first 2 days of life; 34 (71%) of children with annular pancreas were reported to have at least one other congenital abnormality, the most common being trisomy 21 (Down syndrome), seen in 10 (21%). Gastrointestinal abnormalities included intestinal malrotation in 10 of the 48 children (21%), tracheoesophageal fistula in 4 (8.3%), and 1 each of mobile right colon, omphalocele, nonrotation, duodenal atresia, and situs inversus. In addition, 10 children (21%) had significant cardiac anomalies, and genitourinary abnormalities were seen in 5 children (10%).

Therapy for Annular Pancreas

A review of the existing literature published in 1980 concluded that “while there is no single operative procedure of choice, experience militates against any direct attack on the offending annulus” (Kiernan et al, 1980). This conclusion stands, and any attempt to divide the annulus itself risks the formation of a pancreatic fistula. Early pediatric series established duodenal bypass as the treatment of choice, although mortality rates remained high, likely related to the presence of other congenital malformations and the lack of supportive care (Hays et al, 1961; Kiesewetter & Koop, 1954; Merrill & Raffensperger, 1976). Duodenoduodenostomy has replaced duodenojejunostomy as the treatment of choice because it has a lower incidence of postoperative complications, particularly obstruction and blind-loop syndromes (Jimenez et al, 2004). Before the procedure, care should be given to ensure adequate fluid replacement and correction of electrolyte abnormalities. A right upper quadrant incision gives excellent access, and a full examination should be performed to exclude other congenital abnormalities. An end-to-end or side-to-side duodenoduodenostomy should be performed, ensuring adequate mobilization of proximal and distal ends. Where the first part of the duodenum is distended, a tapering duodenoplasty or plication can be performed, although this may not always be required. Consideration should be given to the placement of a gastrostomy tube; however, this should be reserved for those patients who are likely to have long-term problems, such as those with complex gastrointestinal malformations or chromosomal abnormalities. An enteral feeding tube is often useful and allows early feeding to be commenced.

Outcome after surgery has improved markedly, with early mortality rates decreasing from 83% in the 1950s (Kiesewetter & Koop, 1954) to less than 10% in most recent series (Jimenez et al, 2004; Zyromski et al, 2008), largely as a result of improvements in surgical decision making and technique and advances in neonatal intensive care and anesthesia. Deaths in contemporary series are usually attributed to severe associated congenital anomalies.

Pancreatobiliary Maljunction

Pancreatobiliary maljunction was first described by Babbitt in 1969, and it has since been defined as “a congenital anomaly in which a junction of the pancreatic duct and biliary ducts is detected radiologically and/or anatomically outside the duodenal wall” (see Chapter 1B; Todani et al, 1994). It is often associated with congenital bile duct dilation (choledochal cyst; see Chapter 46), which is significant because it results in regurgitation of pancreatic juice into the biliary tree (pancreatobiliary reflux) and of bile into the pancreatic duct (biliopancreatic reflux). It has been associated with a number of pathologic conditions, most notably carcinoma of the biliary tree (see Chapter 50A, Chapter 50B, Chapter 50C, Chapter 50D ).

Pathogenesis

The anatomic relationship between the junction of the duodenum and the pancreatobiliary ducts is subject to significant variation (Suda et al, 1980, 1983). The pancreatic and bile duct may open into the duodenum in one of three configurations: 1) separately, 2) through a single opening with no common channel, or 3) through a single opening with a common channel (Fig. 51.6). Within the wall of the duodenum, the pancreatic and bile ducts are under the control of the sphincter of Oddi; proximal to this extend the sphincter choledochus (of Boyden) and the sphincter pancreaticus. A single opening with a short common channel is usual, but when the common channel extends beyond the duodenal wall, the pancreatobiliary ductal junction is not controlled by these sphincter mechanisms, allowing regurgitation to occur between the two ducts. This is termed pancreatobiliary maljunction, which was reported to have a prevalence of 3.1% in a recent ERCP series (Kamisawa et al, 2007b). A further 3.7% of patients were shown to have a high confluence of the pancreatobiliary ducts, and although sphincter function existed at the junction, the group was still susceptible to the same pathologic consequences as those with maljunction. The incidence of maljunction is higher in Asian compared with Western populations, although the reasons for this remain unclear.

FIGURE 51.6 Normal variations in the configuration of the pancreatic and bile ducts.

(Adapted from Rizzo RJ, Szucs RA, Turner MA, 1995: Congenital abnormalities of the pancreas and biliary tree in adults. Radiographics 15:49.)

The embryologic origins of pancreatobiliary maljunction have not been fully elucidated. Small pancreatic radicals arising from the long common channel have led to the suggestion that it originates from the ventral pancreatic duct (Matsumoto et al, 2001; Suda et al, 1991a, 1991b). In one such hypothesis, it is suggested that the persistence of the left ventral duct, usually seen to regress in normal development, associated with regression of the distal bile duct results in a long common channel (Oi, 1996). An alternative hypothesis suggests that maljunction results from a disturbance in embryologic connections of the terminal bile duct and the ductal system of the ventral pancreas (Matsumoto et al, 2001). A case report of pancreatobiliary maljunction in monozygotic twins provides strong support for a genetic basis for the disease (Yamao et al, 2004).

Diagnosis and Investigation

Maljunction is closely associated with choledochal cyst and in one series was described in all patients with type I choledochal cysts (see Chapter 46; Miyano et al, 1997). Clinical presentation in this context can be at any age and may feature a right upper quadrant mass, hepatomegaly, jaundice, abdominal pain, cholangitis, or pancreatitis. In maljunction without bile duct dilatation, patients may be asymptomatic (30%), or they may be seen with abdominal pain (24%), recurrent acute pancreatitis (18%), obstructive jaundice (18%), or acute cholangitis 9% (Matsumoto et al, 2002). When pancreatic maljunction is suspected, the lack of effect of the sphincter muscle on the pancreatobiliary ductal junction can be confirmed radiologically, and regurgitation can be demonstrated by MRCP, ERCP, operative cholangiography, or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography. Biliary amylase levels have also been shown to be high in this group (Ohta et al, 1990). On hepatobiliary scintigraphy, the passage time from the bile duct to the second part of the duodenum was significantly longer in maljunction patients than in controls (49 ± 13 vs. 3 ± 14 minutes) (Fujii et al, 1991).

Carcinogenesis in Pancreatobiliary Maljunction

The association of bile duct cancer and choledochal cyst is well established (Irwin & Morrison, 1944), and resection of the extrahepatic bile duct and gallbladder with biliary reconstruction is now standard treatment (Edil et al, 2009). A number of published series have described a high incidence of gallbladder cancer in patients with pancreatobiliary maljunction in the absence of a dilated bile duct (see Chapter 49; Chao et al, 1995; Chijiiwa et al, 1995; Elnemr et al, 2001; Kamisawa et al, 2006, 2007b; Kimura et al, 1985; Kinoshita et al, 1984; Mori et al, 1993; Sandoh et al, 1997; Yamauchi et al, 1987). The hydrostatic pressure in the pancreatic duct is greater than that of the bile duct (Carr-Locke & Gregg, 1981; Csendes et al, 1979), so it follows that when free communication exists between the two ducts, pancreatic juice flows from the pancreatic to the bile duct. The pathogenesis of malignant change is not fully characterized but is likely due to the effect of activated pancreatic enzymes on the biliary epithelium, together with biliary stasis. KRAS and P53 mutations have been reported in noncancerous biliary epithelium of patients with maljunction, which may be important given the apparent higher incidence of carcinoma in this group (Hanada et al, 1996, 1999; Kasuya et al, 2009; Matsubara et al, 1996, 2002).

Therapy for Pancreatobiliary Maljunction Without Bile Duct Dilatation

Given the risk of malignant transformation in patients with pancreatobiliary maljunction without biliary dilation, resectional surgery is generally advocated. However, significant controversy exists as to whether a complete excision of the extrahepatic biliary tree is required or just a simple cholecystectomy. Those arguing the former cite case reports of choledochal cyst patients developing cancer in the hepatic duct above the reconstruction after bile duct resection (Thistlethwaite & Horwitz, 1967; Yamamoto et al, 1996). This, together with the P53/KRAS mutation, suggests the biliary epithelium is in a “premalignant state” (Funabiki et al, 1997; Hara et al, 2001; Ng & Lui, 1999; Toufeeq Khan & Manas, 1999; Tuech et al, 2000). Other investigators argue that cholecystectomy alone is sufficient and base this on reasonable follow-up data, albeit in small cohorts, showing no patients developed bile duct malignancy in this group (Aoki et al, 2001; Kusano et al, 2005; Ohuchida et al, 2006; Sugiyama & Atomi, 1998). It is currently impossible to confirm which strategy is correct, and any decision must be made on an individual basis.

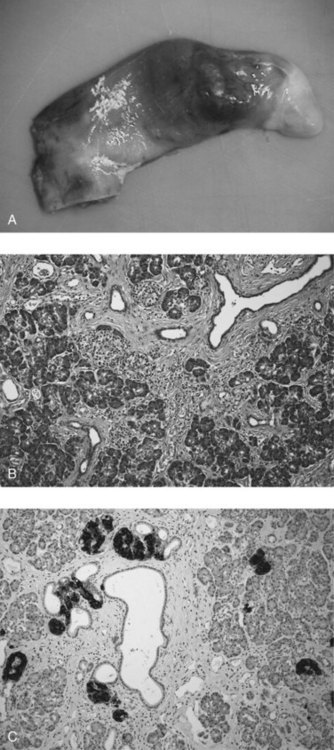

Congenital Cysts of the Pancreas

Of the cystic diseases of the pancreas (see Chapter 57), true congenital cysts are uncommon and comprise less than 1% of the total (Howard, 1989). Cysts may be solitary, but this is rare—fewer than 30 have been described in the world literature. They are usually multiple, and some are associated with a systemic disorder, such as von Hippel–Lindau syndrome or polycystic kidney disease (Boulanger et al, 2003). Enteric duplication cysts of the gastrointestinal tract are also rare (2 in 9000 fetal/neonatal autopsies) (Potter, 1962) and can lie in the pancreatic head in isolation or in communication with the pancreatic duct (Black et al, 1986). They are lined with gastrointestinal mucosa and take a layer of smooth muscle from their associated viscus. Several hypotheses on their embryologic origins exist, but no consensus has been reached (Bentley & Smith, 1960; Bishop & Koop, 1964; Bremer, 1944; Lewis & Thyng, 1908).

Congenital pancreatic cysts are most commonly seen in neonates or infants as an asymptomatic epigastric mass. It is very rare for them to present in adulthood, although case reports do exist (Casadei et al, 1996). In the case of duplication cysts, presentation with acute pancreatitis is not uncommon. This is likely to be due to the secretions of the gastrointestinal mucosa within the cyst activating pancreatic enzymes. Other modes of presentation relate to compression of other structures by the cyst and include abdominal pain, obstructive jaundice, and splenic vein thrombosis (Boulanger et al, 2003).

Diagnosis can be difficult, and most of the published cases describe extensive investigation of patients with recurrent abdominal pain or pancreatitis before the diagnosis being made. In patients with solitary congenital pancreatic cysts, US, CT, and ERCP have all been used in making the diagnosis (Casadei et al, 1996). Enteric duplication cysts involving the head of the pancreas can be differentiated from pseudocysts on US by the identification of hyperechoic muscoa and hypoechoic smooth muscle (Barr et al, 1990). Peristalsis has also been seen in these lesions (Spottswood, 1994). CT helps further characterize the lesion, and MRCP and ERCP can determine ductal relationships (Siddiqui et al, 1998).

Complete resection of solitary pancreatic cysts has been advocated, given that cystic neoplasms represent a possible differential diagnosis (Boulanger et al, 2003). Drainage procedures have been performed successfully, but multiple biopsies of the cyst wall should be taken to exclude malignancy. Drainage procedures have been performed for enteric duplication cysts but are not usually definitive because patients often return with further pain or pancreatitis. When possible, local or mucosal resection is preferable to major resection, such as pancreatoduodenectomy, which should be reserved for when malignancy cannot be excluded. The spleen should be preserved whenever possible, particularly in the pediatric population.

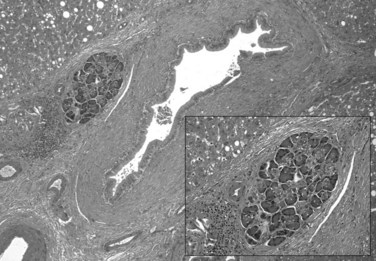

Heterotopic Pancreas

Heterotopic pancreas is defined as pancreatic tissue outside the boundaries of the pancreas that lacks anatomic or vascular continuity with the organ (Fig. 51.7). The first description is credited to Jean Schultz in 1729, and sporadic cases have been described since (Barbosa et al, 1946). Heterotopic pancreas is a congenital anomaly that is usually asymptomatic but can become clinically apparent when the inflamed or enlarged pancreas compresses adjacent viscera. The prevalence in the general population is difficult to determine; estimates range from 0.6% to 13.7% (Barbosa et al, 1946; Feldman & Weinberg, 1952).

The pathogenesis of heterotopic pancreas is unclear. It has been hypothesised that during embryologic development, pancreatic tissue may become attached to the duodenum and be carried proximally or distally as the bowel elongates (Horgan, 1921). This, however, does not explain the rare instances of heterotopic pancreas at sites distant from the gastrointestinal tract, for instance, in the uterine tube (Mason & Quagliarello, 1976). As has been described, the pancreas is endodermal in origin, and contemporary studies are beginning to uncover the mechanisms by which cells destined to become pancreas are specified from surrounding tissues (Kumar & Melton, 2003). The observation that heterotopic pancreas tissue usually drains into the gastrointestinal tract via a primitive duct (Pang, 1988) suggests in situ differentiation rather than migration from elsewhere (Slack, 1995). Thus it is possible that heterotopic pancreas is the result of a process in which cells destined for other endodermal structures are anomalously diverted to a pancreatic fate.

Clinical presentation depends entirely on anatomic site. An early series of 34 patients by Armstrong and colleagues is representative: heterotopic tissue was found in stomach (24%), duodenum (32%), jejunum (29%), Meckel diverticulum (15%; Fig. 51.8), and gallbladder (3%). Occurrences have also been documented in the esophagus, bile duct, spleen, mesentery, and fallopian tubes. In the same series, heterotopic pancreas was thought to be clinically significant in 13 patients (38%) and possibly significant in four patients (12%). All gastric lesions, and four of 11 duodenal lesions, presented with epigastric pain. Two of the duodenal lesions presented with ulcer bleeding and one with chronic anemia.

Investigation and diagnosis again depend on the mode of presentation. In a contemporary series, diagnosis was made at gastroduodenoscopy in 36% and at surgery in 64% (Eisenberger et al, 2004). It was noted that definitive diagnosis was only obtained with histologic assessment. Heterotopic pancreas was the indication for surgery in 36% of cases, and in 45%, it was diagnosed incidentally during surgery. In 18% it was diagnosed on gastroduodenoscopy, and definitive surgical management was not required.

Alazmi WM, et al. Predicting pancreas divisum by inspection of the minor papilla: a prospective study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:422-426.

Anderson SW, Soto JA. Pancreatic duct evaluation: accuracy of portal venous phase 64 MDCT. Abdom Imaging. 2009;34:55-63.

Aoki T, et al. Is preventive resection of the extrahepatic bile duct necessary in cases of pancreaticobiliary maljunction without dilatation of the bile duct? Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2001;31:107-111.

Armstrong CP, et al. The clinical significance of heterotopic pancreas in the gastrointestinal tract. Br J Surg. 1981;68:384-387.

Babbitt DP. [Congenital choledochal cysts: new etiological concept based on anomalous relationships of the common bile duct and pancreatic bulb]. Ann Radiol (Paris). 1969;12:231-240.

Baldwin W. The pancreatic ducts in man together with a study of the microscopic structure of the minor duodenal papilla. Anat Rec. 1911;5:197-228.

Baldwin WM. A specimen of annular pancreas. Anat Rec. 1910;4:299-304.

Barbosa JJ, Dockerty MB, Waugh JM. Pancreatic heterotopia: review of the literature and report of 41 authenticated surgical cases of which 25 were clinically significant. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1946;82:527-542.

Barr LL, et al. Enteric duplication cysts in children: are their ultrasonographic wall characteristics diagnostic? Pediatr Radiol. 1990;20:326-328.

Ben-David K, Falcone RAJr, Matthews JB. Diffuse pancreatic adenocarcinoma identified in an adult with annular pancreas. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:565-568.

Benger JR, Thompson MH. Annular pancreas and obstructive jaundice. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:713-714.

Bentley JFR, Smith JR. Developmental posterior enteric remnants and spinal malformations: the split notochord syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1960;35:76.

Berman LG, et al. A study of the pancreatic duct system in man by the use of vinyl acetate casts of postmortem preparations. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1960;110:391-403.

Bernard JP, et al. Pancreas divisum is a probable cause of acute pancreatitis: a report of 137 cases. Pancreas. 1990;5:248-254.

Bierig L, Chen YK, Shah RJ. Patient outcomes following minor papilla endotherapy (MPE) for pancreas divisum (PD). Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:313A.

Birnstingl M. A study of pancreatography. Br J Surg. 1959;47:128-139.

Bishop HC, Koop CE. Surgical management of duplications of the alimentary tract. Am J Surg. 1964;107:434.

Bitgood MJ, McMahon AP. Hedgehog and Bmp genes are coexpressed at many diverse sites of cell–cell interaction in the mouse embryo. Dev Biol. 1995;172:126-138.

Black PR, Welch KJ, Eraklis AJ. Juxtapancreatic intestinal duplications with pancreatic ductal communication: a cause of pancreatitis and recurrent abdominal pain in childhood. J Pediatr Surg. 1986;21:257-261.

Blair AJIII, Russell CG, Cotton PB. Resection for pancreatitis in patients with pancreas divisum. Ann Surg. 1984;200:590-594.

Borak GD, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes after endoscopic minor papilla therapy in symptomatic patients with pancreas divisum. Pancreas. 2009;38:903-906.

Boulanger SC, et al. Congenital pancreatic cysts in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:1080-1082.

Bragg LE, Thompson JS, Burnett DA. Surgical treatment of pancreatitis associated with pancreas divisum. Nebr Med J. 1988;73:169-173.

Bremer JL. Diverticula and duplications of the intestinal tract. Arch Pathol. 1944;38:132-140.

Brenner P, Duncombe V, Ham JM. Pancreatitis and pancreas divisum: aetiological and surgical considerations. Aust N Z J Surg. 1990;60:899-903.

Britt LG, Samuels AD, Johnson JWJr. Pancreas divisum: is it a surgical disease? Ann Surg. 1983;197:654-662.

Cameron G. Pancreatic anomalies: their morphology, pathology and clinical history. Trans Coll Phys. 1924;46:781.

Carnes ML, Romagnuolo J, Cotton PB. Miss rate of pancreas divisum by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in clinical practice. Pancreas. 2008;37:151-153.

Carr-Locke DL, Gregg JA. Endoscopic manometry of pancreatic and biliary sphincter zones in man. Dig Dis Sci. 1981;26:7-15.

Casadei R, et al. Congenital true pancreatic cysts in young adults: case report and literature review. Pancreas. 1996;12:419-421.

Chao TC, Jan YY, Chen MF. Primary carcinoma of the gallbladder associated with anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal junction. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;21:306-308.

Charpy A. Variéteés et anomalies des canaux pancréatiques. J Anat Physiol. 1898;34:720-734.

Chijiiwa K, Kimura H, Tanaka M. Malignant potential of the gallbladder in patients with anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal junction: the difference in risk between patients with and without choledochal cyst. Int Surg. 1995;80:61-64.

Choudari CP, et al. Risk of pancreatitis with mutation of the cystic fibrosis gene. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1358-1363.

Clairmont P, Hadjipetros P. Zur Anatomie des Ductus Wirsungianus und Ductus Santorini: Ihre Bedeutung für die Duodenal-resektion wegen. Ulcus. 1920;159:251-283.

Claviez A, Heger S, Bohring A. Annular pancreas in two sisters. Am J Med Genet. 1995;58:384.

Cohn JA, et al. Relation between mutations of the cystic fibrosis gene and idiopathic pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:653-658.

Coleman SD, et al. Endoscopic treatment in pancreas divisum. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:1152-1155.

Cooperman M, et al. Surgical management of pancreas divisum. Am J Surg. 1982;143:107-112.

Cotton PB. Cannulation of the papilla of Vater by endoscopy and retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Gut. 1972;13:1014-1025.

Cotton PB. Duodenoscopic papillotomy at the minor papilla of Vater for recurrent dorsal pancreatitis. Endosc Dig. 1978;3:27-28.

Cotton PB. Congenital anomaly of pancreas divisum as cause of obstructive pain and pancreatitis. Gut. 1980;21:105-114.

Csendes A, et al. Pressure measurements in the biliary and pancreatic duct systems in controls and in patients with gallstones, previous cholecystectomy, or common bile duct stones. Gastroenterology. 1979;77:1203-1210.

Dawson W, Langman J. An anatomical-radiological study on the pancreatic duct pattern in man. Anat Rec. 1961;139:59-68.

Delhaye M, Engelholm L, Cremer M. Pancreas divisum: congenital anatomic variant or anomaly? Contribution of endoscopic retrograde dorsal pancreatography. Gastroenterology. 1985;89:951-958.

Ecker A. Malformation of pancreas and heart. Ztschr F Rat Med. 1862;14:254.

Edil BH, Olino K, Cameron JL. The current management of choledochal cysts. Adv Surg. 2009;43:221-232.

Eisenberger CF, et al. Heterotopic pancreas: clinical presentation and pathology with review of the literature. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:854-858.

Elnemr A, et al. Anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal junction without bile duct dilatation in gallbladder cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:382.

Ertan A. Long-term results after endoscopic pancreatic stent placement without pancreatic papillotomy in acute recurrent pancreatitis due to pancreas divisum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:9-14.

Feldman M, Weinberg T. Aberrant pancreas: a cause of duodenal syndrome. JAMA. 1952;148:893.

Fogel EL, et al. Annular pancreas (AP) in the adult: experience at a large pancreatobiliary endoscopy center. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:308A.

Fogel EL, et al. Does endoscopic therapy favorably affect the outcome of patients who have recurrent acute pancreatitis and pancreas divisum? Pancreas. 2007;34:21-45.

Foo FJ, et al. Ampullary carcinoma associated with an annular pancreas. JOP. 2007;8:50-54.

Fujii H, et al. Bile flow analysis by hepatobiliary scintigraphy in the terminal bile duct in patients with congenital malformations of the pancreatico-biliary ductal system. J Gastroenterol. 1991;26:201-208.

Funabiki T, et al. Surgical strategy for patients with pancreaticobiliary maljunction without choledocal dilatation. Keio J Med. 1997;46:169-172.

Gelrud A, et al. Analysis of cystic fibrosis gene product (CFTR) function in patients with pancreas divisum and recurrent acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1557-1562.

Gregg JA. Pancreas divisum: its association with pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1977;134:539-543.

Gregg JA, Monaco AP, McDermott WV. Pancreas divisum: results of surgical intervention. Am J Surg. 1983;145:488-492.

Hanada K, et al. K-ras and p53 mutations in stage I gallbladder carcinoma with an anomalous junction of the pancreaticobiliary duct. Cancer. 1996;77:452-458.

Hanada K, et al. Gene mutations of K-ras in gallbladder mucosae and gallbladder carcinoma with an anomalous junction of the pancreaticobiliary duct. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1638-1642.

Hand BH. An anatomical study of the choledochoduodenal area. Br J Surg. 1963;50:486-494.

Hara H, et al. Surgical treatment for non-dilated biliary tract with pancreaticobiliary maljunction should include excision of the extrahepatic bile duct. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:984-987.

Hays DM, Greaney EMJr, Hill JT. Annular pancreas as a cause of acute neonatal duodenal obstruction. Ann Surg. 1961;153:103-112.

Hebrok M, et al. Regulation of pancreas development by hedgehog signaling. Development. 2000;127:4905-4913.

Heiss FW, Shea JA. Association of pancreatitis and variant ductal anatomy: dominant drainage of the duct of Santorini. Am J Gastroenterol. 1978;70:158-162.

Helly KK. Beitrage zur Anatomie des Pancreas und seiner Ausfuhrungsgange. Arch F Mikr Anat. 1898;52:773.

Hendricks SK, Sybert VP. Association of annular pancreas and duodenal obstruction: evidence for Mendelian inheritance? Clin Genet. 1991;39:383-385.

Heyries L, et al. Long-term results of endoscopic management of pancreas divisum with recurrent acute pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:376-381.

Hjorth E. Contributions to the knowledge of pancreatic reflux as an etiologic factor in chronic affections of the gallbladder: an experimental study. Acta Chir Scand. 1947;96:1-76.

Horgan EJ. Accessory pancreatic tissue: report of two cases. Arch Surg. 1921;2:521.

Howard JM. Cystic neoplasms and true cysts of the pancreas. Surg Clin North Am. 1989;69:651-665.

Hulvat MC, et al. Annular pancreas in identical twin newborns. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:e19-e21.

Hyrtl J. [Pancreas accessorium and pancreas divisum.]. Sitz Mathematisch-Naturwiss Classe d K Akad Wissenschaften (Wien). 1865;52:275.

Irwin ST, Morrison JE. Congenital cyst of the central bile duct containing stones and undergoing cancerous change. Br J Surg. 1944;32:319-321.

Jackson LG, Apostolides P. Autosomal dominant inheritance of annular pancreas. Am J Med Genet. 1978;1:319-321.

Jarikji Z, et al. The tetraspanin Tm4sf3 is localized to the ventral pancreas and regulates fusion of the dorsal and ventral pancreatic buds. Development. 2009;136:1791-1800.

Jimenez JC, et al. Annular pancreas in children: a recent decade’s experience. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:1654-1657.

Kamisawa T, et al. Annular pancreas associated with carcinoma in the dorsal part of pancreas divisum. Int J Pancreatol. 1995;17:207-211.

Kamisawa T, et al. A new embryologic hypothesis of annular pancreas. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:277-278.

Kamisawa T, et al. Biliary carcinoma risk in patients with pancreaticobiliary maljunction and the degree of extrahepatic bile duct dilatation. Hepatogastroenterology. 2006;53:816-818.

Kamisawa T, et al. Pancreatographic investigation of embryology of complete and incomplete pancreas divisum. Pancreas. 2007;34:96-102.

Kamisawa T, et al. The presence of a common channel and associated pancreaticobiliary diseases: a prospective ERCP study. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:173-179.

Kasuya K, et al. p53 gene mutation and p53 protein overexpression in a patient with simultaneous double cancer of the gallbladder and bile duct associated with pancreaticobiliary maljunction. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:376-381.

Keith RG, et al. Dorsal duct sphincterotomy is effective long-term treatment of acute pancreatitis associated with pancreas divisum. Surgery. 1989;106:660-666.

Keyl R. Über die Beziehungen des Santorinischen Ganges zum Zwölffingerdarm und zum Wirsungschen. Gang Morp Jb. 1925;55:345.

Kiernan PD, et al. Annular pancreas: Mayo clinic experience from 1957 to 1976 with review of the literature. Arch Surg. 1980;115:46-50.

Kiesewetter WB, Koop CE. Annular pancreas in infancy. Surgery. 1954;36:146-159.

Kim SK, Hebrok M, Melton DA. Notochord to endoderm signaling is required for pancreas development. Development. 1997;124:4243-4252.

Kim SK, MacDonald RJ. Signaling and transcriptional control of pancreatic organogenesis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:540-547.

Kimura K, et al. Association of gallbladder carcinoma and anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal union. Gastroenterology. 1985;89:1258-1265.

Kinoshita H, et al. Carcinoma of the gallbladder with an anomalous connection between the choledochus and the pancreatic duct: report of 10 cases and review of the literature in Japan. Cancer. 1984;54:762-769.

Kleitsch WP. Anatomy of the pancreas: a study with special reference to the duct system. AMA Arch Surg. 1955;71:795-802.

Kozarek RA, et al. Endoscopic approach to pancreas divisum. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:1974-1981.

Kumar M, Melton D. Pancreas specification: a budding question. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2003;13:401-407.

Kumar M, et al. Signals from lateral plate mesoderm instruct endoderm toward a pancreatic fate. Dev Biol. 2003;259:109-122.

Kusano T, et al. Whether or not prophylactic excision of the extrahepatic bile duct is appropriate for patients with pancreaticobiliary maljunction without bile duct dilatation. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52:1649-1653.

Lainakis N, et al. Annular pancreas in two consecutive siblings: an extremely rare case. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2005;15:364-368.

Lammert E, Cleaver O, Melton D. Induction of pancreatic differentiation by signals from blood vessels. Science. 2001;294:564-567.

Lans JI, et al. Endoscopic therapy in patients with pancreas divisum and acute pancreatitis: a prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:430-434.

Lawrence C, Stefan AM, Howell DA. Endoscopic appearance of the minor papilla predicts findings at pancreatography. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;55:2412-2416.

Lecco TM. Zur morphologie des pancreas annulare. Sitzungsber Wien Akad Wiss Math-Nat KI. 1910;119:391-406.

Lehman GA, et al. Pancreas divisum: results of minor papilla sphincterotomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:1-8.

Lewis FT, Thyng FW. The regular occurrence of intestinal diverticula in embryos of the pig, rabbit, and man. Am J Anat. 1908;7:505-519.

Liguory C, et al. [Pancreas divisum: clinical and therapeutic study in man: apropos of 87 cases]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1986;10:820-825.

Linder JD, et al. Long-term response to pancreatic duct stent placement in symptomatic patients with pancreas divisum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:208A.

Linder JD, et al. Minor papilla sphincterotomy in patients with symptomatic pancreas divisum: long-term efficacy and complications. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:208A.

Litingtung Y, et al. Sonic hedgehog is essential to foregut development. Nat Genet. 1998;20:58-61.

MacFadyen UM, Young ID. Annular pancreas in mother and son. Am J Med Genet. 1987;27:987-989.

Madura JA. Pancreas divisum: stenosis of the dorsally dominant pancreatic duct—a surgically correctable lesion. Am J Surg. 1986;151:742-745.

Madura JA, et al. Surgical sphincteroplasty in 446 patients. Arch Surg. 2005;140:504-511.

Manfredi R, et al. Pancreas divisum and “santorinicele”: diagnosis with dynamic MR cholangiopancreatography with secretin stimulation. Radiology. 2000;217:403-408.

Mason TE, Quagliarello JR. Ectopic pancreas in the fallopian tube. Report of a first case. Obstet Gynecol. 1976;48:755.

Matsubara T, et al. K-ras point mutations in cancerous and noncancerous biliary epithelium in patients with pancreaticobiliary maljunction. Cancer. 1996;77:1752-1757.

Matsubara T, et al. K-ras and p53 gene mutations in noncancerous biliary lesions of patients with pancreaticobiliary maljunction. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2002;9:312-321.

Matsumoto Y, et al. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction: etiologic concepts based on radiologic aspects. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:614.

Matsumoto Y, et al. Recent advances in pancreaticobiliary maljunction. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2002;9:45-54.

McCarthy J, Geenen JE, Hogan WJ. Preliminary experience with endoscopic stent placement in benign pancreatic diseases. Gastrointest Endosc. 1988;34:16-18.

McCune WS, Shorb PE, Moscovitz H. Endoscopic cannulation of the ampulla of Vater: a preliminary report. Ann Surg. 1968;167:752-756.

Mehnen H. Die Bedeutung der Mundungsverhaltnisse von Gallen und Pankreasgang für die Entstehung der Gallensteine. Arch Klin Chir. 1938;1938:559.

Merrill JR, Raffensperger JG. Pediatric annular pancreas: twenty years’ experience. J Pediatr Surg. 1976;11:921-925.

Millbourn E. Calibre and appearance of the pancreatic ducts and relevant clinical problems. Acta Chir Scand. 1959;118:286-303.

Mitchell CE, Marshall DG, Reid WD. Preampullary congenital duodenal obstruction in a father and son. J Pediatr Surg. 1993;28:1582-1583.

Mitchell CJ, et al. Clinical relevance of an unfused pancreatic duct system. Gut. 1979;20:1066-1071.

Miyano T, Urao M, Yamataka A. Choledochal cyst. Curr Opin Pediatr. 1997;9:283-288.

Montgomery RC, et al. Report of a case of annular pancreas of the newborn in two consecutive siblings. Pediatrics. 1971;48:148-150.

Mori K, et al. Association between gallbladder cancer and anomalous union of the pancreaticobiliary ductal system. Hepatogastroenterology. 1993;40:56.

Näätänen E. Über die Pankreasgange mit besonderer Berucksichtigung des Vorkommens eines Ductus Santorini. Z Anat Entwicklungsgesch. 1941;111:355.

Ng WT, Lui KW. Anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction without choledochal cyst. Br J Surg. 1999;86:1476-1477.

Nobukawa B, et al. An annular pancreas derived from paired ventral pancreata, supporting Baldwin’s hypothesis. Pancreas. 2000;20:408-410.

O’Connor KW, Lehman GA. An improved technique for accessory papilla cannulation in pancreas divisum. Gastrointest Endosc. 1985;31:13-17.

Odgers PNB. Some observations on the development of the ventral pancreas in man. J Anat. 1930;65:1-7.

Ohta T, et al. Clinical experience of biliary tract carcinoma associated with anomalous union of the pancreaticobiliary ductal system. Jpn J Surg. 1990;20:36-43.

Ohuchida J, et al. Long-term results of treatment for pancreaticobiliary maljunction without bile duct dilatation. Arch Surg. 2006;141:1066-1070.

Oi I. The development of the ventral pancreas and anomalous bilio-pancreatic junction. J Biliary Tract Pancreas. 1996;17:723-729.

Opie E, 1903: The Anatomy of the Pancreas. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins Hospital Bulletin. pp. 229–232

Pang LC. Pancreatic heterotopia: a reappraisal and clinicopathologic analysis of 32 cases. South Med J. 1988;81(10):1264-1275.

Petrone MC, Arcidiacono PG, Testoni PA. Endoscopic ultrasonography for evaluating patients with recurrent pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1016-1022.

Phillip J, Koch H, Classen M. Variations and anomalies of the papilla of Vater, the pancreas and the biliary system. Endoscopy. 1974;6:70-77.

Potter EL. Pathology of the fetus and infant. Acad Med. 1962;37:160.

Ramalho-Santos M, Melton DA, McMahon AP. Hedgehog signals regulate multiple aspects of gastrointestinal development. Development. 2000;127:2763-2772.

Ravitch MM, Woods ACJ. Annular pancreas. Ann Surg. 1950;132:1116-1127.

Richter JM, et al. Association of pancreas divisum and pancreatitis, and its treatment by sphincteroplasty of the accessory ampulla. Gastroenterology. 1981;81:1104-1110.

Rienhoff WF. Pancreatitis: an anatomic study of the pancreatic and extra-hepatic biliary systems. Arch Surg. 1945;51:205-219.

Rogers JC, Harris DJ, Holder T. Annular pancreas in a mother and daughter. Am J Med Genet. 1993;45:116.

Rösch W, et al. The clinical significance of the pancreas divisum. Gastrointest Endosc. 1976;22(4):206-207.

Rusnak CH, et al. Pancreatitis associated with pancreas divisum: results of surgical intervention. Am J Surg. 1988;155:641-643.

Russell RC, Wong NW, Cotton PB. Accessory sphincterotomy (endoscopic and surgical) in patients with pancreas divisum. Br J Surg. 1984;71:954-957.

Sahel J, et al. Clinico-pathological conditions associated with pancreas divisum. Digestion. 1982;23:1-8.

Sandoh N, Shirai Y, Hatakeyama K. Incidence of anomalous union of the pancreaticobiliary ductal system in biliary cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 1997;44:1580-1583.

Sandrasegaran K, et al. Annular pancreas in adults. Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:455-460.

Satterfield ST, et al. Clinical experience in 82 patients with pancreas divisum: preliminary results of manometry and endoscopic therapy. Pancreas. 1988;3:248-253.

Schirmer AM. Beitrag zur Geschichte und Anatomie des Pankreas. Dissertation: University of Basel; 1893.

Schmieden V, Sebening W. Chirurgie des Pankreas. Arch Klin Chir. 1927;148:319.

Schwarz M. Das Gangsystem der Bauchspeicheldruse und seine Bedeutung für die Duodenal-resektion. Dtsch Z Chir. 1926;198:358.

Sencan A, et al. Symptomatic annular pancreas in newborns. Med Sci Monit. 2002;8:434-437.

Shan YS, Sy ED, Lin PW. Annular pancreas with obstructive jaundice: beware of underlying neoplasm. Pancreas. 2002;25:314-316.

Sharer N, et al. Mutations of the cystic fibrosis gene in patients with chronic pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:645-652.

Sherman S, et al. Randomized controlled trial of minor papilla sphincterotomy (MiES) in pancreas divisum (Pdiv) patients with pain only. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:125A.

Siddiqui AM, et al. Enteric duplications of the pancreatic head: definitive management by local resection. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:1117-1120.

Sigfusson BF, Wehlin L, Lindstrom CG. Variants of pancreatic duct system of importance in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. observations on autopsy specimens. 1983;24:113-128.

Slack JM. Developmental biology of the pancreas. Development. 1995;121:1569-1580.

Smanio T. Proposed nomenclature and classification of the human pancreatic ducts and duodenal papillae: study based on 200 post mortems. Int Surg. 1969;52:125-134.

Soehendra N, et al. Endoscopic dilatation and papillotomy of the accessory papilla and internal drainage in pancreas divisum. Endoscopy. 1986;18:129-132.

Spottswood SE. Peristalsis in duplication cyst: a new diagnostic sonographic finding. Pediatr Radiol. 1994;24:344-345.

Stafford D, Prince VE. Retinoic acid signaling is required for a critical early step in zebrafish pancreatic development. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1215-1220.

Staritz M, Meyer zum Buschenfelde KH. Elevated pressure in the dorsal part of pancreas divisum: the cause of chronic pancreatitis? Pancreas. 1988;3:108-110.

Stern CD. A historical perspective on the discovery of the accessory duct of the pancreas, the ampulla ‘of Vater’ and pancreas divisum. Gut. 1986;27:203-212.

Stimec B, et al. Ductal morphometry of ventral pancreas in pancreas divisum: comparison between clinical and anatomical results. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1996;28:76-80.

Suda K, Matsumoto Y, Miyano T. Narrow duct segment distal to choledochal cyst. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:1259-1263.

Suda K, Miyano T, Hashimoto K. The choledocho-pancreatico-ductal junction in infantile obstructive jaundice diseases. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1980;30(2):187-194.

Suda K, Mogaki M, Matsumoto Y. Gross dissection and immunohistochemical studies on branch fusion type of ventral and dorsal pancreatic ducts: a case report. Surg Radiol Anat. 1991;13:333-337.

Suda K, et al. An abnormal pancreatico-choledocho-ductal junction in cases of biliary tract carcinoma. Cancer. 1983;52(11):2086-2088.

Sugawa C, et al. Pancreas divisum: is it a normal anatomic variant? Am J Surg. 1987;153:62-67.

Sugiyama M, Atomi Y. Anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction without congenital choledochal cyst. Br J Surg. 1998;85:911-916.

Thistlethwaite JR, Horwitz A. Choledochal cyst followed by carcinoma of the hepatic duct. South Med J. 1967;60:872-874.

Thompson MH, Williamson RC, Salmon PR. The clinical relevance of isolated ventral pancreas. Br J Surg. 1981;68:101-104.

Tiso N, et al. BMP signalling regulates anteroposterior endoderm patterning in zebrafish. Mech Dev. 2002;118:29-37.

Todani T, Akita E, Eto T. The Japanese Study Group on Pancreaticobiliary Maljunction: diagnostic criteria of pancreaticobiliary maljunction. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1994;1:219-221.

Toufeeq Khan TF, Manas DM. Anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction without congenital choledochal cyst. Br J Surg. 1999;86:843-844.

Tuech JJ, et al. Cancer of the gallbladder associated with pancreaticobiliary maljunction without bile duct dilatation in a european patient. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2000;7:336-338.

Tulassay Z, Papp J. New clinical aspects of pancreas divisum. Gastrointest Endosc. 1980;26:143-146.

Vitale GC, et al. Long-term follow-up of endoscopic stenting in patients with chronic pancreatitis secondary to pancreas divisum. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:2199-2202.

Warshaw AL, et al. Evaluation and treatment of the dominant dorsal duct syndrome (pancreas divisum redefined). Am J Surg. 1990;159:59-64.

Yamamoto J, et al. Bile duct carcinoma arising from the anastomotic site of hepaticojejunostomy after the excision of congenital biliary dilatation: a case report. Surgery. 1996;119:476-479.

Yamao K, et al. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction in monozygotic twins: a case report. Hepato-gastroenterology. 2004;51:675-678.

Yamauchi S, et al. Anomalous junction of pancreaticobiliary duct without congenital choledochal cyst: a possible risk factor for gallbladder cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:20-24.

Yasui A, et al. Duodenal obstruction due to annular pancreas associated with pancreatic head carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 1995;42:1017-1022.

Zyromski NJ, et al. Annular pancreas: dramatic differences between children and adults. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:1019-1025.