Chapter 311 Congenital Anomalies

311.1 Esophageal Atresia and Tracheoesophageal Fistula

Seema Khan and Susan R. Orenstein

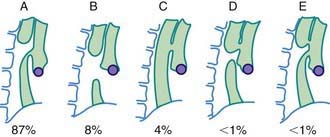

Esophageal atresia (EA) is the most common congenital anomaly of the esophagus, affecting ∼1/4,000 neonates. Of these, >90% have an associated tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF). In the most common form of EA, the upper esophagus ends in a blind pouch and the TEF is connected to the distal esophagus. The types of EA and TEF and their relative frequencies are shown in Figure 311-1. The exact cause is still unknown; associated features include advanced maternal age, European ethnicity, obesity, low socioeconomic status, and tobacco smoking. This defect has survival rates of >90%, owing largely to improved neonatal intensive care, earlier recognition, and appropriate intervention. Infants weighing <1,500 g at birth have the highest risk for mortality. Fifty percent of infants are nonsyndromic without other anomalies, and the rest have associated anomalies, most often associated with the VATER or VACTERL (vertebral, anorectal, [cardiac], tracheal, esophageal, renal, radial, [limb]) syndrome. These syndromes generally are associated with normal intelligence. Despite low concordance among twins and the low incidence of familial cases, genetic factors have a role in the pathogenesis of TEF in some patients as suggested by discrete mutations in syndromic cases: Feingold syndrome (N-MYC), CHARGE syndrome (coloboma of the eye, central nervous system anomalies; heart defects; atresia of the choanae; retardation of growth and/or development; genital and/or urinary defects [hypogonadism]; ear anomalies and/or deafness) (CHD7), and anophthalmia-esophageal-genital syndrome (SOX2).

Diagnosis

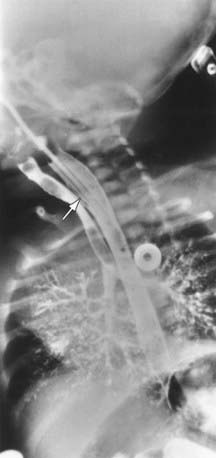

In the setting of early-onset respiratory distress, the inability to pass a nasogastric or orogastric tube in the newborn suggests esophageal atresia. Maternal polyhydramnios might alert the physician to EA. Plain radiography in the evaluation of respiratory distress might reveal a coiled feeding tube in the esophageal pouch and/or an air-distended stomach, indicating the presence of a coexisting TEF (Fig. 311-2). Conversely, pure EA can manifest as an airless scaphoid abdomen. In isolated TEF (H type), an esophagogram with contrast medium injected under pressure can demonstrate the defect (Fig. 311-3). Alternatively, the orifice may be detected at bronchoscopy or when methylene blue dye injected into the endotracheal tube during endoscopy is observed in the esophagus during forced inspiration.

Achildi O, Grewal H. Congenital anomalies of the esophagus. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2007;40:219-244.

Castilloux J, Noble AJ, Faure C. Risk factors for short- and long-term morbidity in children with esophageal atresia. J Pediatr. 2010;156:755-760.

Keckler SJ, St Peter SD, Valusek PA, et al. VACTERL anomalies in patients with esophageal atresia: an updated delineation of the spectrum and review of the literature. Pediatr Surg Int. 2007;23:309-313.

Shaw-Smith C. Oesophageal atresia, tracheo-oesophageal fistula and the VACTERL association: review of genetics and epidemiology. J Med Genet. 2006;43:545-554.

Spitz L. Esophageal atresia. Lessons I have learned in a 40-year experience. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:1635-1640.