Congenital Anomalies

Phakomatoses (Disseminated Hereditary Hamartomas)

General Information

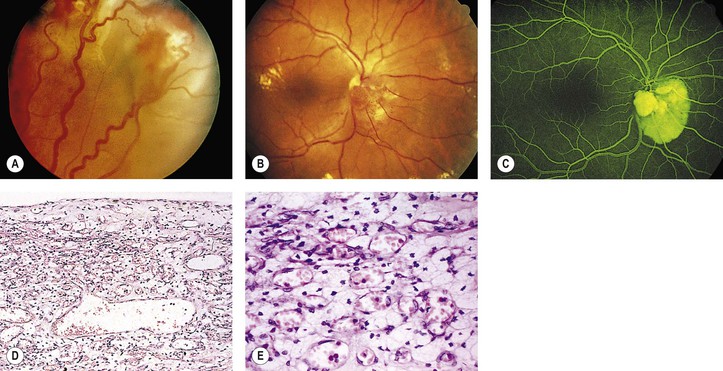

Angiomatosis Retinae [von Hippel’s Disease (VHL)]

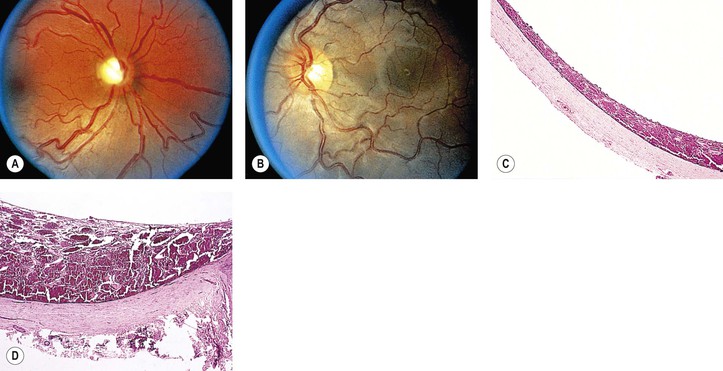

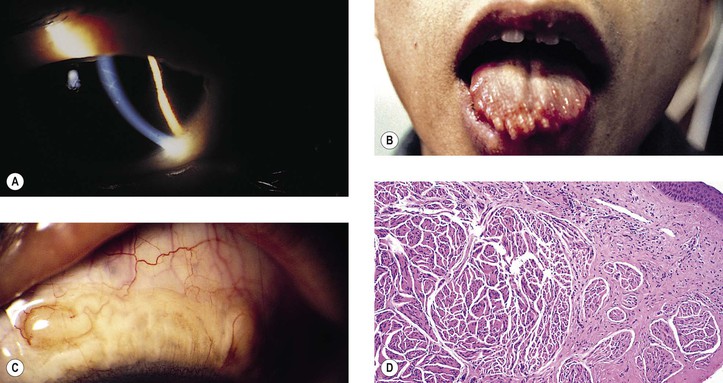

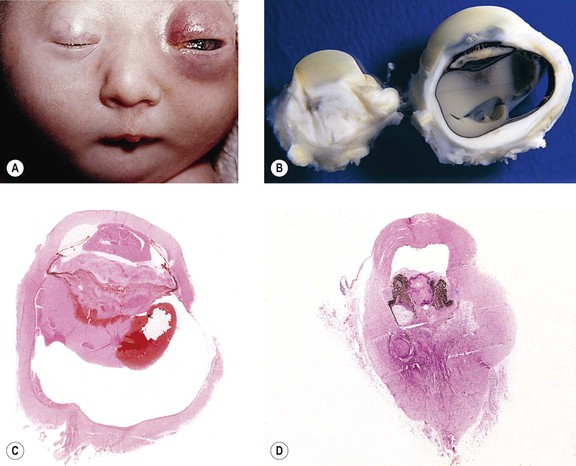

A. The onset of ocular symptoms is usually in young adulthood. Retinal capillary hemangiomas (hemangioblastomas) occur in more than 50% of patients (Fig. 2.1), and central nervous system lesions occur in 72% of patients.

II. Ocular findings

A. A retinal capillary hemangioma (see Chapter 14), usually supplied by large feeder vessels, may occur in the optic nerve or in any part of the retina. Retinal exudates, often in the macula even when the tumor is peripheral, result when serum leaks from the abnormal tumor blood vessels.

III. Systemic findings

A. Retinal capillary hemangioma may occur in the cerebellum, brainstem, and spinal cord.

B. Cysts of pancreas and kidney are common.

C. Hypernephroma and pheochromocytoma (usually bilateral) occur infrequently.

IV. Histology

A. The basic lesion is a capillary hemangioma (hemangioblastoma) (see Chapter 14) composed of endothelial cells and pericytes. Between the capillaries are foamy stromal cells that appear to be of glial origin.

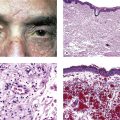

Meningocutaneous Angiomatosis [Encephalotrigeminal Angiomatosis; Sturge–Weber Syndrome (SWS)]

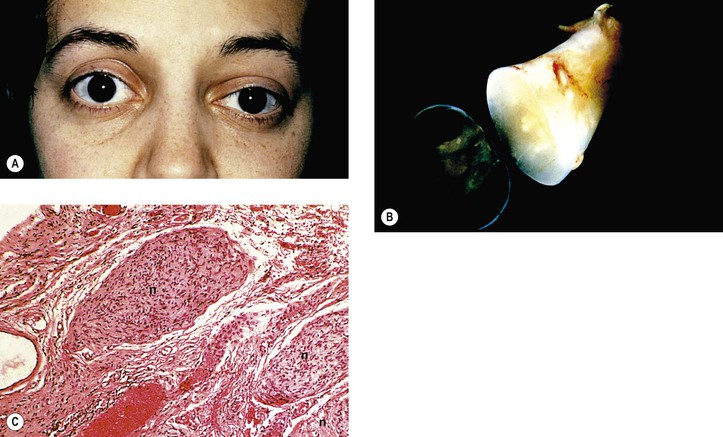

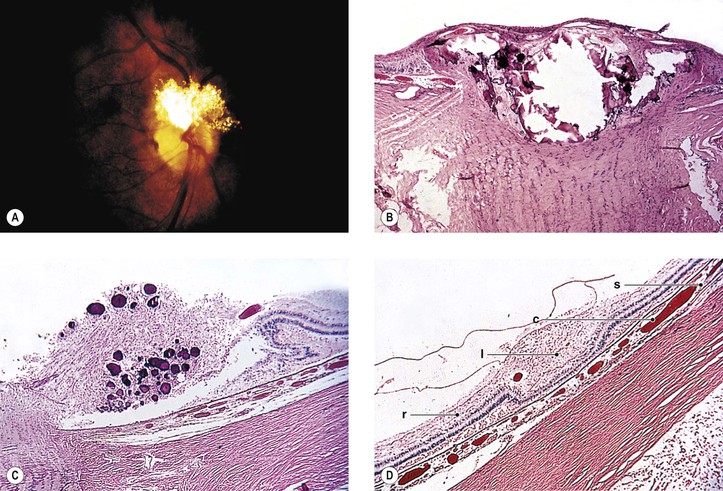

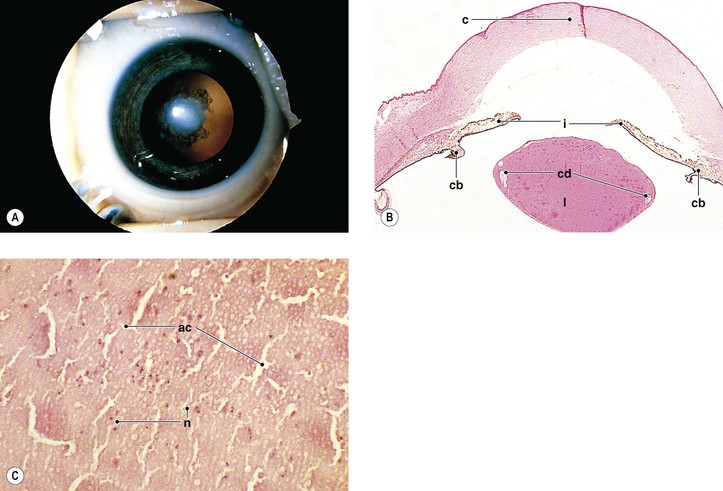

A. SWS (Fig. 2.2) usually consists of unilateral (rarely bilateral) meningeal calcification, facial nevus flammeus (port wine stain and phakomatosis pigmentovascularis), frequently along the distribution of the trigeminal nerve, and congenital glaucoma.

B. The condition is congenital (heredity does not seem to be an important factor).

II. Ocular findings

A. The most common intraocular finding is a cavernous hemangioma (see Chapter 14) of the choroid on the side of the facial nevus flammeus.

B. A cavernous hemangioma or telangiectasis (see Chapter 14) of the lids on the side of the facial nevus flammeus is common.

1. The lids, especially the upper, are usually involved.

III. Systemic findings

C. Seizures and mental retardation are common.

IV. Histology

A. The basic lesion in the skin of the face (including lids), the meninges, and the choroid is a cavernous hemangioma (see Chapter 14). In addition, telangiectasis (see Chapter 14) of the skin of the face may occur.

B. Congenital glaucoma may be present.

C. Secondary complications, such as microcystoid degeneration of the overlying retina (see Chapter 11) and leakage of serous fluid (see Chapter 11), are common.

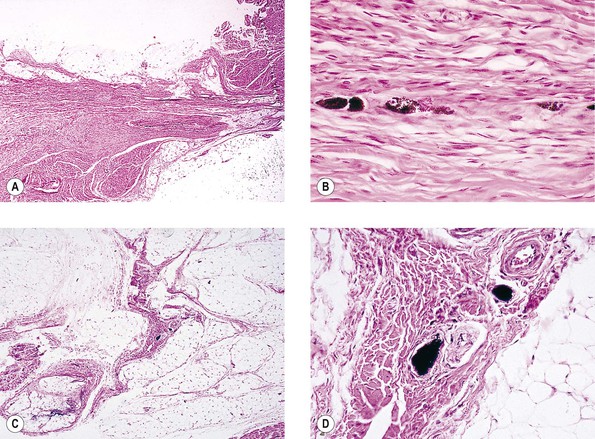

Neurofibromatosis (Figs. 2.3–2.5)

I. Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1: von Recklinghausen’s disease or peripheral neurofibromatosis)

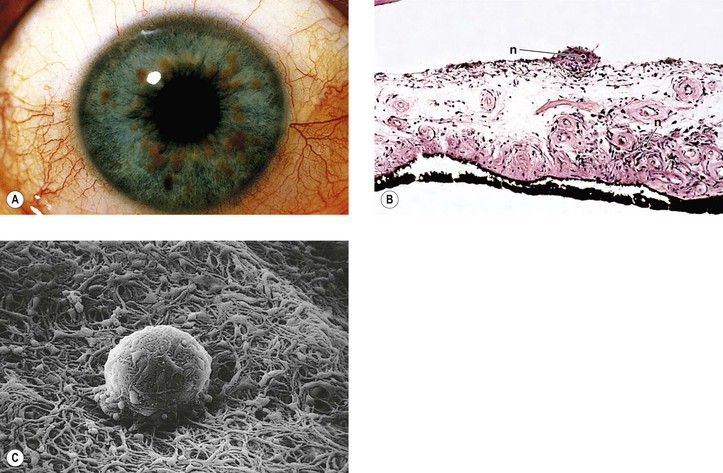

3. Thickening of corneal and conjunctival nerves and congenital glaucoma

C. Histology

1. In the skin and orbit, a diffuse, irregular proliferation of peripheral nerve elements (predominantly Schwann cells) results in an unencapsulated neurofibroma, composed of numerous cells that contain elongated, basophilic nuclei and faintly granular cytoplasm associated with fine, wavy, “maiden-hair,” immature collagen fibers.

a. Special stains often show nerve fibers in the tumor.

b. Vascularity is quite variable from tumor to tumor and in the same tumor.

2. In the eye, the lesion may be a melanocytic nevus (see Chapter 17), slight or massive involvement of the uvea (usually choroid) by a mixture of hamartomatous neural and nevus elements, or a glial hamartoma.

II. Neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF-2; central neurofibromatosis, bilateral acoustic neurofibromatosis)

1. Diagnosis of NF-2 is made if a person has either bilateral eighth-nerve tumors or a first-degree relative who has NF-2; and either a unilateral eighth-nerve tumor or two or more of the following: neurofibroma, meningioma (especially primary nerve sheath meningioma), glioma, schwannoma, ependymoma, or juvenile posterior subcapsular lenticular opacity.

a. NF-2 is transmitted as an irregular autosomal-dominant (prevalence about 1 in 40,000).

b. The responsible gene is located on chromosome 22 (band 22q12).

2. Combined pigment epithelial and retinal hamartomas may occur.

III. Because of the neuromas, café-au-lait spots, and prominent corneal nerves that may be found, the condition of multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) type IIB must be differentiated from neurofibromatosis.

A. MEN, a familial disorder, is classified into three groups.

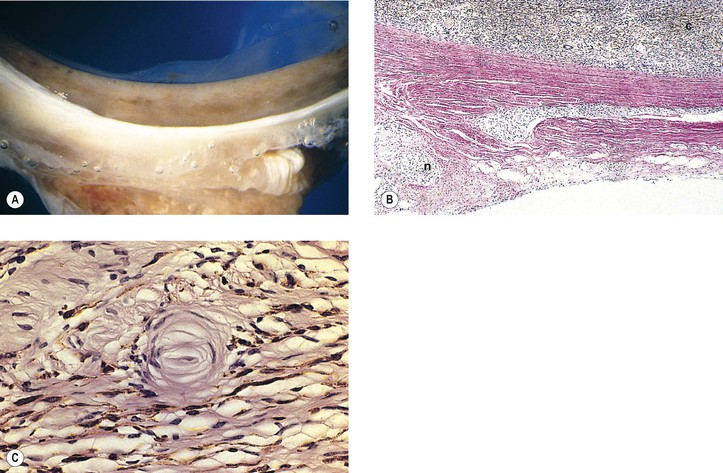

3. Type IIB (Fig. 2.6; 50% autosomal-dominant and 50% sporadic inheritance; also called type III) consists of medullary thyroid carcinoma and, less often, pheochromocytoma.

1. In MEN I, the predisposing genetic linkage is assigned to chromosome region 11q13.

2. In MEN IIA and IIB, the predisposing genetic linkage is assigned to chromosome region 10q11.2.

Tuberous1 Sclerosis (Bourneville’s Disease; Pringle’s Disease)

B. The prognosis is poor (death occurs in 75% of patients by 20 years of age).

II. Ocular findings (Fig. 2.7)

A. Adenoma sebaceum (angiofibroma) of lids

III. Systemic findings

B. Adenoma sebaceum of the skin of the face occurs in 83% of patients.

IV. Histology

A. Giant drusen of the optic disc occur anterior to the lamina cribrosa and are glial hamartomas (see Chapter 13).

B. Adenoma sebaceum are not tumors of the sebaceous gland apparatus but are angiofibromas (see Chapter 6).

C. Glial hamartomas in the cerebrum (usually in the walls of the lateral ventricles over the basal ganglia) and neural retina are composed of large, fusiform astrocytes separated by a coarse and nonfibrillated, or finer and fibrillated, matrix formed from the astrocytic cell processes.

2. Calcospherites may be prominent, especially in older lesions.

Other Phakomatoses

Numerous other phakomatoses occur. Ataxia–telangiectasia (Louis–Bar syndrome), an immunodeficient disorder, consists of an autosomal-recessive inheritance pattern (gene localized to chromosome 11q22), progressive cerebellar ataxia, oculocutaneous telangiectasia, and frequent pulmonary infections; arteriovenous communication of retina and brain (Wyburn–Mason syndrome) consists of a familial pattern, mental changes, and arteriovenous communication of the midbrain and retina (see Chapter 14) associated with facial nevi. Most other phakomatoses are extremely rare or do not have salient ocular findings.

Chromosomal Aberrations

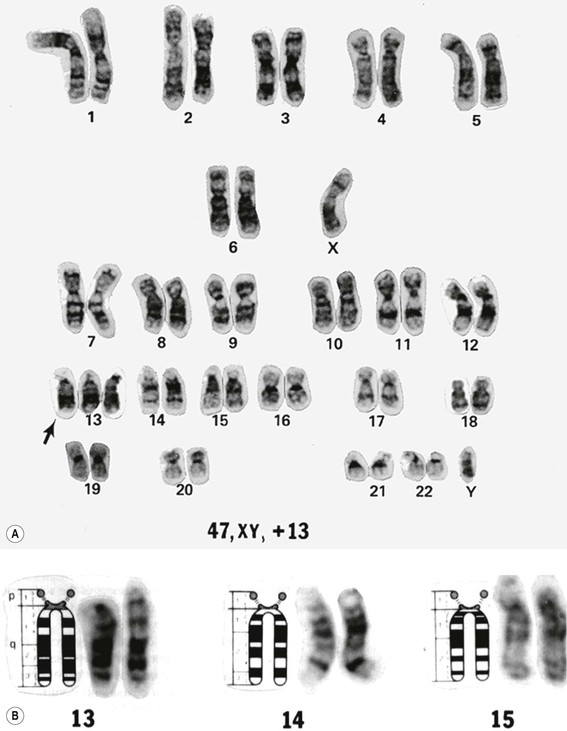

I. The normal human cell is diploid and contains 46 chromosomes: 44 autosomal chromosomes and 2 sex chromosomes (XX in a female and XY in a male).

A. Individual chromosomes may be arranged in an array according to morphologic characteristics. The resultant array of chromosomes is called a karyotype.

1. A karyotype is made by photographing a cell in metaphase and then cutting out the individual chromosomes and arranging them in pairs in chart form according to predetermined morphologic criteria (i.e., karyotype; Fig. 2.8). The paired chromosomes are designated by numbers.

B. To differentiate the chromosomes, special techniques are used, such as autoradiography or chromosomal band patterns, as shown with fluorescent quinacrine (see Fig. 2.8).

II. Chromosomes may be normal in total number (i.e., 46), but individual chromosomes may have structural alterations.

III. Chromosomes may also be abnormal in total number, either with too many or with too few.

Trisomy 8

See later, under Mosaicism.

Trisomy 13 (47,13+; Patau’s Syndrome)

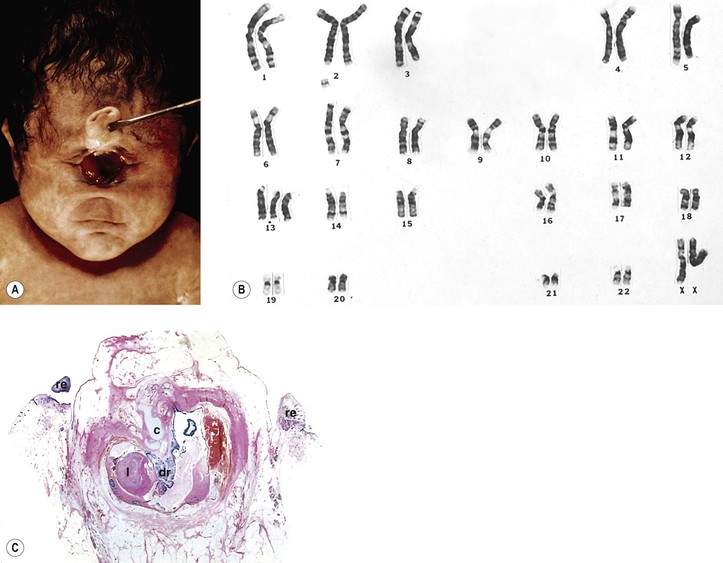

A. Trisomy 13 results from an extra chromosome in the 13 pair of autosomal chromosomes (i.e., one set of chromosomes exists in triplicate rather than as a pair; see Fig. 2.8). It is caused by an accidental failure of disjunction of one pair of chromosomes during meiosis (meiotic nondisjunction) and has no sex predilection.

B. The condition, present in one in 14,000 live births, is usually lethal by age six months.

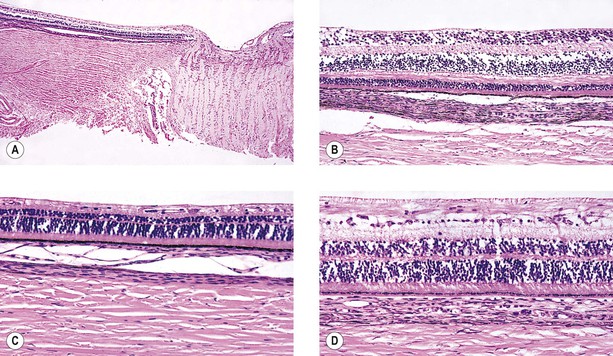

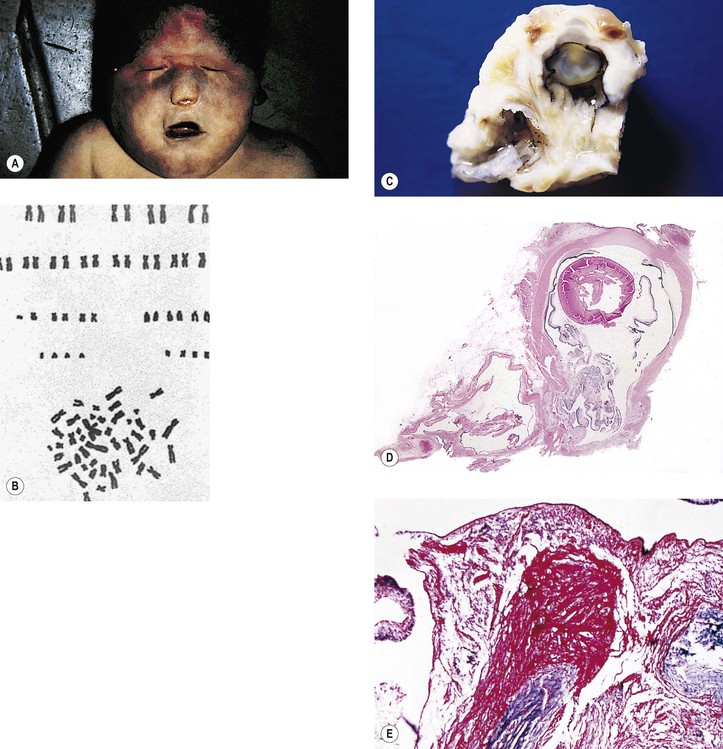

D. Ocular anomalies, usually severe, occur in all cases (Fig. 2.9; see Fig. 2.15).

III. Ocular findings, usually severe, occur in all cases (see Figs. 2.9 and 2.15).

D. Central and peripheral dysgenesis of the cornea and iris (see Chapter 8) is present in at least 60% of eyes.

IV. Histology

Trisomy 18 (47,18+; Edwards’ Syndrome)

A. Trisomy 18 has an extra chromosome in the 18 pair of autosomal chromosomes.

C. Ocular malformations, usually minor, occur in approximately 50% of patients.

IV. Histology—especially related to hyperplasia, hypertrophy, and cellular abnormalities

B. Posterior subcapsular cataracts, minor neural retinal changes (gliosis and hemorrhage), and optic atrophy may be seen.

1. The retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) may show hypopigmented or hyperpigmented areas.

Trisomy 21 (47,21+; Down’s Syndrome; Mongolism)

A. Trisomy 21 results from an extra chromosome in the 21 pair of autosomal chromosomes.

III. Ocular findings include hypertelorism; oblique or arched palpebral fissures; epicanthus; ectropion; upper-eyelid eversion; speckled iris (Brushfield spots); esotropia, high myopia; rosy optic disc with excessive retinal vessels crossing its margin; generalized attenuation of fundus pigmentation regardless of iris coloration; peripapillary and patchy peripheral areas of pigment epithelial atrophy; choroidal vascular “sclerosis”; chronic blepharoconjunctivitis; keratoconus (sometimes acute hydrops; see Fig. 8.54); and lens opacities.

IV. Histology

Triploidy

Chromosome 4 Deletion Defect

The chromosome 4 deletion defect (4p–) results from a partial deletion of the short arm of chromosome 14 (46,4p–). Also known as the Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome (or Wolf’s syndrome), it consists of profound mental retardation, antimongoloid slant, epicanthal folds, hypertelorism, ptosis, strabismus, nystagmus, cataract, and iris colobomas.

Chromosome 5 Deletion Defect (46,5p–; Cri du Chat Syndrome)

Chromosome 11 Deletion Defect

Deletion of chromosome 11p (aniridia–genitourinary–mental retardation syndrome—AGR triad) shows aniridia as its main ocular finding.

Chromosome 13 Deletion Defect

See Chapter 18.

Chromosome 17 Deletion (17p11.2; Smith–Magenis Syndrome)

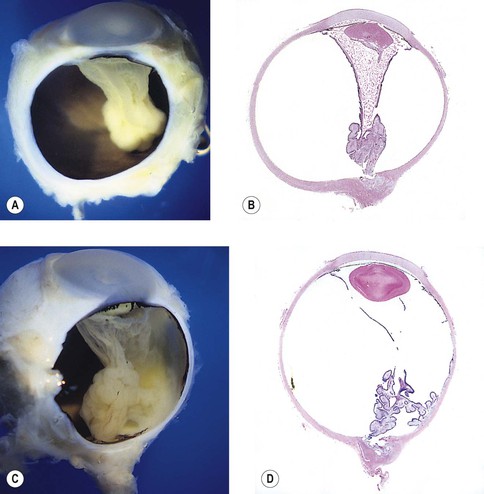

Chromosome 18 Deletion Defect (46,18p–; 46,18q–; or 46,18r; Partial 18 Monosomy (Fig. 2.10)

B. Affected patients usually live a normal life span.

IV. Histology

A. Microphthalmos with cyst (see Chapter 14) and uveal colobomas are discussed elsewhere (see Chapter 9).

Infectious Embryopathy

Congenital Rubella Syndrome (Gregg’s Syndrome)

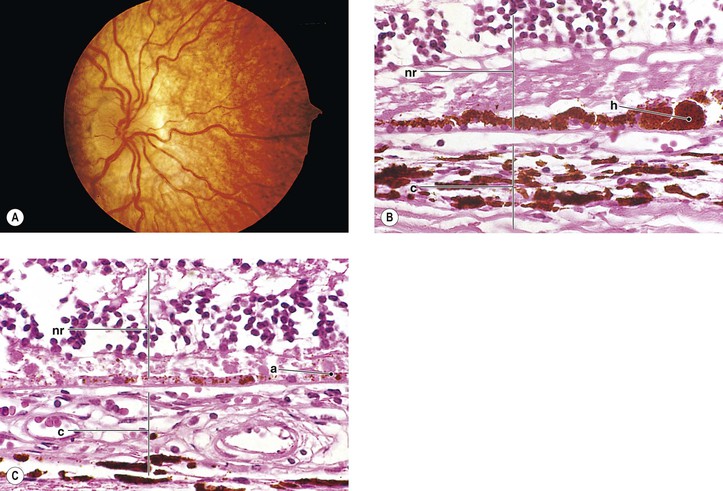

III. Ocular findings include cataract, congenital glaucoma, iris abnormalities, and a secondary pigmentary retinopathy (Figs 2.12 and 2.13).

IV. The rubella virus can pass through the placenta, infect the fetus, and cause abnormal embryogenesis.

V. Histology

E. Other findings, such as Peters’ anomaly and Axenfeld’s anomaly, may occasionally be seen.

Cytomegalic Inclusion Disease

See Chapter 4.

Congenital Syphilis

See Chapters 4 and 8.

Toxoplasmosis

See Chapter 4.

Drug Embryopathy

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) (Fig. 2.14)

III. Ocular findings include narrow palpebral fissures, epicanthal folds, ptosis; blepharophimosis; strabismus; severe myopia; microcornea; Peters’ anomaly (see Fig. 2.14); iris dysplasia; glaucoma; hypoplasia of the optic nerve head; and microphthalmia.

Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD) (Fig. 2.15)

Other Congenital Anomalies

Cyclopia and Synophthalmos

I. Cyclopia and synophthalmos (Fig. 2.16) are conditions in which anterior brain and midline mesodermal structures develop anomalously (holoprosencephaly—also called arhinencephaly and holotelencephaly).

A. The conditions are incompatible with life.

B. The prevalence is approximately one in 13,000 to 20,000 live births.

V. Histology

Microphthalmos

I. Microphthalmos (see Figs. 2.9–2.11) is a congenital condition in which the affected eye is smaller than normal at birth (<15 mm in greatest diameter; normal eye at birth varies between 16 and 19 mm).

II. Three types of microphthalmos are recognized:

A. Pure microphthalmos alone (nanophthalmos or simple microphthalmos), wherein the eye is smaller than normal in size but has no other gross abnormalities except for a high lens/eye volume.

1. Such eyes are usually hypermetropic and may have macular hypoplasia.

B. Microphthalmos with cyst (see Fig. 2.10 and Chapter 9 and 14).

Walker–Warburg Syndrome

I. Walker–Warburg syndrome (Fig. 2.18) is a lethal, autosomal-recessive, oculocerebral disorder. The diagnosis is based on at least four abnormalities: type II lissencephaly, cerebellar malformation, retinal malformation, and congenital muscular dystrophy.

Oculocerebrorenal Syndrome of Miller

Subacute Necrotizing Encephalomyelopathy (Leigh’s Disease)

I. Leigh’s disease is a mitochondrial enzymatic deficiency (point mutation at position 8993 in the adenosine triphosphatase subunit gene of mtDNA) that shares similar ocular findings to those seen in Kearns–Sayre syndrome, another mitochondrial disorder (see Chapter 14).

B. The disease has an autosomal-recessive inheritance pattern.

C. The symptoms are nonspecific, and a familial history helps make the diagnosis.

Meckel’s Syndrome (Dysencephalia Splanchnocystica; Gruber’s Syndrome)

II. Ocular findings include cryptophthalmos, dysplasia of the palpebral fissure, hypertelorism or hypotelorism, clinical anophthalmos, microphthalmos (Fig. 2.20), Peters’ anomaly, aniridia, retinal dysplasia, and cataract.

Potter’s Syndrome

Menkes’ Kinky-Hair Disease

I. Menkes’ kinky-hair disease is characterized by early, progressive psychomotor deterioration; seizures; spasticity; hypothermia; pili torti; bone changes resembling those of scurvy; tortuosity of cerebral arteries from fragmentation of the internal elastic lamina; and characteristic facies.

B. Incidence is 1 in 100,000 to 250,000 live births.

II. The disease is caused by a generalized copper deficiency in the body.

A. Levels of serum copper, copper oxidase, and ceruloplasmin are abnormally low.

IV. Histologically, the main findings consist of diminished neural retinal ganglion cells and a thinned nerve fiber layer, decrease in and demyelination of optic nerve axons, loss of pigment from retinal and iris pigment epithelial cells, and microcysts of iris pigment epithelial cells (Fig. 2.21).

Ectrodactyly–Ectodermal Dysplasia (EEC)

Trichothiodystrophy (TD)

Dwarfism

I. Ocular anomalies occur frequently in many different types of dwarfism.

A. Dwarfism secondary to mucopolysaccharidoses (see Chapter 8)

B. Dwarfism secondary to osteogenesis imperfecta (see Chapter 8)

C. Dwarfism secondary to stippled epiphyses (Conradi’s syndrome) with cataracts

D. Dwarfism secondary to Cockayne’s syndrome with retinal degeneration and optic atrophy (see Chapter 11)

E. Dwarfism secondary to Lowe’s syndrome (see Chapter 10)

F. The syndrome of dwarfism, myotonia, diffuse bone disease, myopia, and blepharophimosis

I. Achondroplastic dwarfism with mesodermal dysgenesis of cornea and iris

J. Ateleiotic dwarfism with soft, wrinkled skin of lids

M. Cartilage-hair hypoplastic dwarfism with fine, sparse hair of eyebrows and cilia and trichiasis

II. The histologic features are described in the appropriate sections under the individual tissues.

Other Syndromes

Access the complete reference list online at ![]()

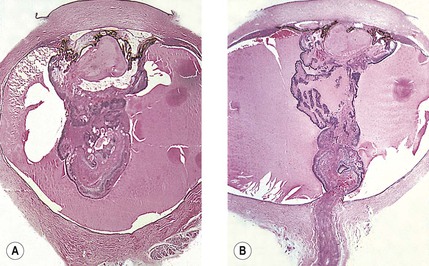

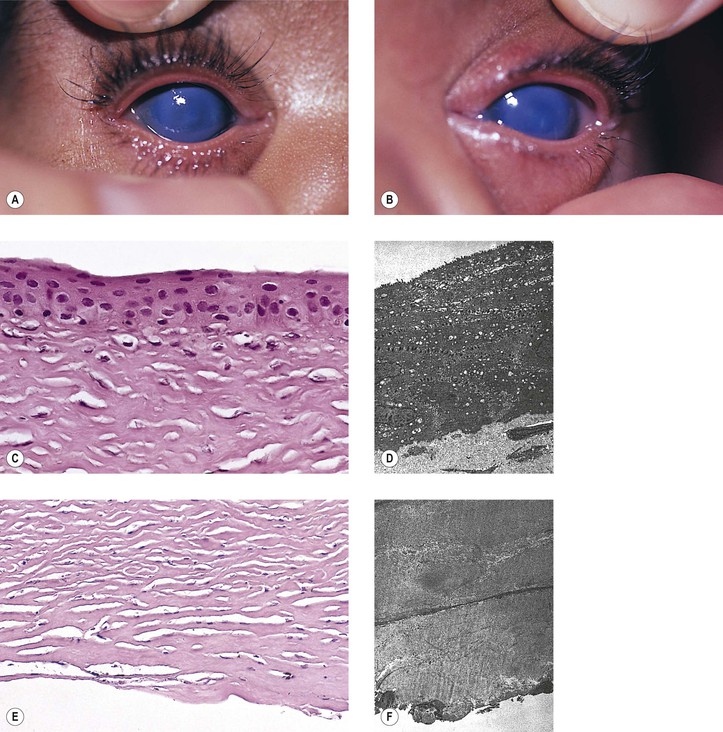

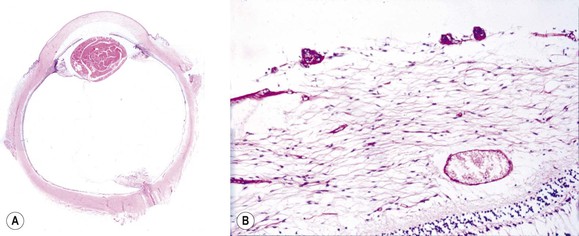

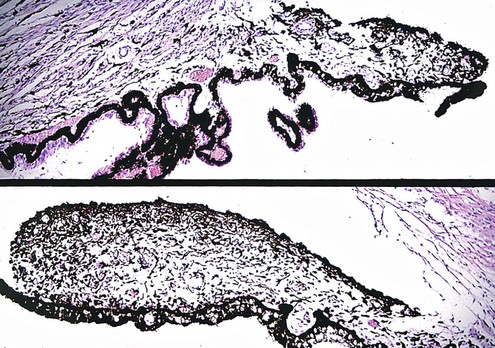

-month-old, mentally retarded, microcephalic child had clinical “aniridia” and congenital cortical and nuclear cataract in addition to bilateral Wilms’ tumor. Top and bottom show different planes of section to demonstrate rudimentary iris having both uveal and neuroepithelial layers but lacking sphincter and dilator muscles. Almost all cases of clinical aniridia turn out to be iris hypoplasia.

-month-old, mentally retarded, microcephalic child had clinical “aniridia” and congenital cortical and nuclear cataract in addition to bilateral Wilms’ tumor. Top and bottom show different planes of section to demonstrate rudimentary iris having both uveal and neuroepithelial layers but lacking sphincter and dilator muscles. Almost all cases of clinical aniridia turn out to be iris hypoplasia.