Combined spinal-epidural blockade

Applied anatomy

The essence of a CSE block is single-shot administration of intrathecal anesthetic or analgesic agents along with placement of a catheter into the epidural space. The applied anatomy of a CSE block is the same as that for subarachnoid and epidural blockade (see Chapter 123, Epidural Anesthesia, Figure 123-1).

Contraindications

Contraindications for CSE block are the same as those for all neuraxial blocks (Table 124-1).

Table 124-1

Absolute and Relative Contraindications to Neuraxial Anesthesia/Analgesia

| Absolute | Relative |

| Patient refusal Bacteremia/sepsis Increased intracranial pressure Infection at needle insertion site Shock or severe hypovolemia Coagulopathy or therapeutic anticoagulation* |

Preexisting neurologic disease Severe psychiatric disease or dementia Aortic stenosis Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction Various congenital heart conditions (absolute contraindication if severe) Deformities or previous surgery of the spinal column |

Advantages

The onset of anesthesia or analgesia is faster.

The onset of anesthesia or analgesia is faster.

The total dose of local anesthetic agent required to achieve analgesia/anesthesia is smaller than the dose necessary with an epidural-only technique, thus reducing the risk of local anesthetic toxicity. This may ultimately result in lower systemic and fetal (if used for labor and delivery) concentrations of local anesthetic agents.

The total dose of local anesthetic agent required to achieve analgesia/anesthesia is smaller than the dose necessary with an epidural-only technique, thus reducing the risk of local anesthetic toxicity. This may ultimately result in lower systemic and fetal (if used for labor and delivery) concentrations of local anesthetic agents.

For obstetric cases, intrathecal opioids can be administered as the sole agent, without the addition of local anesthetic drugs, providing analgesia for the first stage of labor with no motor block.

For obstetric cases, intrathecal opioids can be administered as the sole agent, without the addition of local anesthetic drugs, providing analgesia for the first stage of labor with no motor block.

Epidural catheters placed during a CSE technique are less likely to fail than are epidural catheters placed during an epidural-only technique. This is likely because the epidural space is verified by the return of cerebrospinal fluid through the spinal needle.

Epidural catheters placed during a CSE technique are less likely to fail than are epidural catheters placed during an epidural-only technique. This is likely because the epidural space is verified by the return of cerebrospinal fluid through the spinal needle.

Subsequent epidural dosing may provide greater sacral nerve root coverage when a prior dural hole has been made during a CSE technique. This likely occurs from translocation of epidural drugs into the intrathecal space. In obstetric anesthesia, this may decrease the incidence of sacral sparing during the second stage of labor even if the dose of the intrathecally administered local anesthetic agent has worn off before the onset of the second stage of labor.

Subsequent epidural dosing may provide greater sacral nerve root coverage when a prior dural hole has been made during a CSE technique. This likely occurs from translocation of epidural drugs into the intrathecal space. In obstetric anesthesia, this may decrease the incidence of sacral sparing during the second stage of labor even if the dose of the intrathecally administered local anesthetic agent has worn off before the onset of the second stage of labor.

During labor, more rapid cervical dilation may be associated with the use of a CSE block.

During labor, more rapid cervical dilation may be associated with the use of a CSE block.

In anesthesia for cesarean delivery, a CSE (with a full surgical intrathecal dose) results in less intraoperative discomfort, better muscle relaxation, less shivering, and less vomiting than with an epidural-only technique and, if the epidural catheter is left in place, an option for providing continued postoperative analgesia.

In anesthesia for cesarean delivery, a CSE (with a full surgical intrathecal dose) results in less intraoperative discomfort, better muscle relaxation, less shivering, and less vomiting than with an epidural-only technique and, if the epidural catheter is left in place, an option for providing continued postoperative analgesia.

Disadvantages

Determining the adequacy of the epidural catheter for surgical anesthesia may be delayed.

Determining the adequacy of the epidural catheter for surgical anesthesia may be delayed.

Intrathecally administered opioids can cause pruritus.

Intrathecally administered opioids can cause pruritus.

Theoretically, the risk of infection may be increased because the subarachnoid space is accessed.

Theoretically, the risk of infection may be increased because the subarachnoid space is accessed.

When used for labor analgesia, intrathecally administered opioid medications may increase the incidence of post analgesia fetal heart rate decelerations; however, this disadvantage is controversial, and the complex discussion is beyond the scope of this chapter.

When used for labor analgesia, intrathecally administered opioid medications may increase the incidence of post analgesia fetal heart rate decelerations; however, this disadvantage is controversial, and the complex discussion is beyond the scope of this chapter.

Equipment and technique

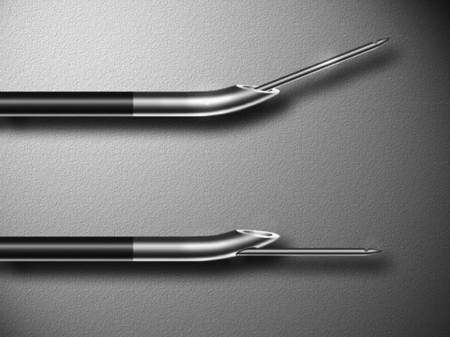

CSE blockades are typically performed via a needle-through-needle technique with traditional epidural and spinal needles (Figure 124-1). When the needle-through-needle technique is performed, a sterile field is created at the procedure site, the skin and subcutaneous tissue are infiltrated with a local anesthetic agent, and an epidural needle is inserted into the ligamentum flavum. Loss of resistance with air or saline is used to identify the epidural space. A spinal needle is then advanced through the epidural needle into the subarachnoid space. The spinal needle must be longer than the epidural needle to allow dural puncture, projecting 13 to 17 mm beyond the tip of the epidural needle. Following the appearance of cerebrospinal fluid, the intrathecal anesthetic or analgesic agent is injected, and the spinal needle is removed. Finally, a catheter is advanced through the epidural needle into the epidural space, and the epidural needle is removed.

Other CSE techniques include the use of specially designed CSE epidural needles that include a guide for the spinal needle alongside the outer wall of the epidural needle or a guide incorporated into the epidural needle wall (Figure 124-1). These guided needles make it possible to place an epidural catheter before intrathecally administering drugs. However, many anesthesiologists believe that these specially designed needles offer little advantage.