Chapter 1 Clinical overview and phenomenology of movement disorders

Fundamentals

The quotation from William Osler is an apt introduction to this chapter, which offers a description of the various phenomenologies of movement disorders. Movement disorders can be defined as neurologic syndromes in which there is either an excess of movement or a paucity of voluntary and automatic movements, unrelated to weakness or spasticity (Table 1.1). The former are commonly referred to as hyperkinesias (excessive movements), dyskinesias (unnatural movements), and abnormal involuntary movements. In this text, the term dyskinesias is used most often, but all are interchangeable. The five major categories of dyskinesias in alphabetical order are chorea, dystonia, myoclonus, tics, and tremor. Table 1.1 presents the complete list.

| Hypokinesias |

Distinguishing between organic and psychogenic causation requires expertise in recognizing the various phenomenologies. Psychogenic movement disorders are covered in Chapter 25.

Those who are interested in keeping up-to-date in the field of movement disorders should refer to the journal Movement Disorders, published 12 times per year by The Movement Disorder Society, Inc. (www.movementdisorders.org). The journal, which is accompanied by two DVDs per year, comes with Movement Disorder Society membership, which is open to all interested medical professionals.

Categories of movements

It is important to note that not all of the hyperkinesias in Table 1.1 are technically classified as abnormal involuntary movements, commonly called AIMS. Movements can be categorized into one of four classes: automatic, voluntary, semivoluntary (also called unvoluntary) (Lang, 1991; Tourette Syndrome Classification Study Group, 1993; Fahn, 2005), and involuntary (Jankovic, 1992). Automatic movements are learned motor behaviors that are performed without conscious effort, e.g., walking an accustomed route, and tapping of the fingers when thinking about something else. Voluntary movements are intentional (planned or self-initiated) or externally triggered (in response to some external stimulus; e.g., turning the head toward a loud noise or withdrawing a hand from a hot plate). Intentional voluntary movements are preceded by the Bereitschaftspotential (or readiness potential), a slow negative potential recorded over the supplementary motor area and contralateral premotor and motor cortex appearing 1–1.5 seconds prior to the movement. The Bereitschaftspotential does not appear with other movements, including the externally triggered voluntary movements (Papa et al., 1991). In some cases, learned voluntary motor skills are incorporated within the repertoire of the movement disorder, such as camouflaging choreic movements or tics by immediately following them with voluntarily executed movements, so-called parakinesias. Semivoluntary (or unvoluntary) movements are induced by an inner sensory stimulus (e.g., need to “stretch” a body part or need to scratch an itch) or by an unwanted feeling or compulsion (e.g., compulsive touching or smelling). Many of the movements occurring as tics or as a response to various sensations (e.g., akathisia and the restless legs syndrome) can be considered unvoluntary because the movements are usually the result of an action to nullify an unwanted, unpleasant sensation. Unvoluntary movements usually are suppressible. Involuntary movements are often non-suppressible (e.g., most tremors and myoclonus), but some can be partially suppressible (e.g., some tremors, chorea, dystonia, stereotypies and some tics) (Koller and Biary, 1989).

The origins of abnormal movements

Many movement disorders are associated with pathologic alterations in the basal ganglia or their connections. The basal ganglia are that group of gray matter nuclei lying deep within the cerebral hemispheres (caudate, putamen, and pallidum), the diencephalon (subthalamic nucleus), the mesencephalon (substantia nigra), and the mesencephalic-pontine junction (pedunculopontine nucleus) (see Chapter 3). There are some exceptions to this general rule. Pathology of the cerebellum or its pathways typically results in impairment of coordination (asynergy, ataxia), misjudgment of distance (dysmetria), and intention tremor. Myoclonus and many forms of tremors do not appear to be related primarily to basal ganglia pathology, and often arise elsewhere in the central nervous system, including cerebral cortex (cortical reflex myoclonus), brainstem (cerebellar outflow tremor, reticular reflex myoclonus, hyperekplexia, and rhythmical brainstem myoclonus such as palatal myoclonus and ocular myoclonus), and spinal cord (rhythmical segmental myoclonus and non-rhythmic propriospinal myoclonus). Moreover, many myoclonic disorders are associated with diseases in which the cerebellum is involved, such as those causing the Ramsay Hunt syndrome of progressive myoclonic ataxia (see Chapter 20). The peripheral nervous system can give rise to abnormal movements also, such as the painful legs–moving toes syndrome (Marsden, 1994). It is not known for certain which part of the brain is associated with tics, although the basal ganglia and the limbic structures have been implicated. Certain localizations within the basal ganglia are classically associated with specific movement disorders: substantia nigra with bradykinesia and rest tremor; subthalamic nucleus with ballism; caudate nucleus with chorea; and putamen with dystonia.

Historical perspective

The neurologic literature contains a number of seminal papers, reviews and books that emphasized and established movement disorders as associated with the basal ganglia pathology (Alzheimer, 1911; Fischer, 1911; Wilson, 1912; Hunt, 1917; Vogt and Vogt, 1920; Jakob, 1923; Putnam et al., 1940; Denny-Brown, 1962; Martin, 1967).

An historical perspective of movement disorders can be gained by listing the dates when the various clinical entities were first introduced (Table 1.2).

Table 1.2 Some notable historical descriptions of movement disorders

| Year | Source | Entity |

|---|---|---|

| Bible | Reference to tremor in the aged | |

| Trembling associated with fear and strong emotion | ||

| 1567 | Paracelsus | Mercury-induced tremor |

| 1652 | Tulpius | Spasmodic torticollis |

| 1685 | Willis | Restless legs syndrome |

| 1686 | Sydenham | Sydenham chorea |

| 1817 | Parkinson | Parkinson disease |

| 1825 | Itard | Tourette syndrome |

| 1830 | Bell | Writer’s cramp |

| 1837 | Couper | Manganese-induced parkinsonism |

| 1848 | Grisolle | Primary writing tremor |

| 1871 | Hammond | Athetosis |

| 1871 | Traube | Spastic dysphonia |

| 1871 | Steinthal | Apraxia |

| 1872 | Huntington | Huntington disease |

| 1872 | Mitchell | Jumpy stumps |

| 1874 | Kahlbaum | Catatonia |

| 1878 | Beard | Jumpers |

| 1881 | Friedreich | Myoclonus |

| 1885 | Gilles de la Tourette | Tourette syndrome |

| 1885 | Gowers | Paroxysmal kinesigenic choreoathetosis |

| 1886 | Spencer | Palatal myoclonus |

| 1887 | Dana | Hereditary tremor |

| 1887 | Wood | Cranial dystonia |

| 1889 | Benedikt | Benedikt syndrome |

| 1891 | Unverricht | Progressive myoclonus epilepsy (Unverricht–Lundborg disease) |

| 1895 | Schultze | Myokymia |

| 1900 | Dejerine/Thomas | Olivopontocerebellar atrophy |

| 1900 | Liepmann | Apraxia |

| 1901 | Haskovec | Akathisia |

| 1903 | Batten | Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis |

| 1904 | Holmes | Midbrain (“rubral”) tremor |

| 1908 | Schwalbe | Familial dystonia |

| 1910 | Meige | Oromandibular dystonia |

| 1911 | Oppenheim | Dystonia musculorum deformans |

| 1911 | Lafora | Lafora disease |

| 1912 | Wilson | Wilson disease |

| 1914 | Lewy | Lewy bodies in Parkinson disease |

| 1916 | Henneberg | Cataplexy |

| 1917 | Hunt | Progressive pallidal atrophy |

| 1920 | Creutzfeldt | Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease |

| 1921 | Jakob | Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease |

| 1921 | Hunt | Dyssynergia cerebellaris myoclonica (Ramsay Hunt syndrome) |

| 1922 | Hallervorden/Spatz | Pantothenate kinase deficiency (neurodegenerative disorder with brain iron deposition-1) |

| 1923 | Sicard | Akathisia |

| 1924 | Fleischhacker | Striatonigral degeneration |

| 1926 | Davidenkow | Myoclonic dystonia |

| 1927 | Goldsmith | Hereditary chin quivering |

| 1927 | Orzechowski | Opsoclonus |

| 1931 | Herz | Myorhythmia |

| 1931 | Guillain/Mollaret | Palato-pharyngo-laryngo-oculo-diaphragmatic myoclonus |

| 1932 | De Lisi | Hypnic jerks |

| 1933 | Spiller | Fear of falling |

| 1933 | Scherer | Striatonigral degeneration |

| 1940 | Mount/Reback | Paroxysmal nonkinesigenic dyskinesia (paroxysmal dystonic choreoathetosis) |

| 1941 | Louis-Bar | Ataxia-telangiectasia |

| 1943 | Kanner | Autism |

| 1944 | Asperger | Autism |

| 1946 | Titeca/van Bogaert | Dentatorubral-pallidoluysian degeneration |

| 1949 | Alexander | Alexander disease |

| 1953 | Adams/Foley | Asterixis |

| 1953 | Symonds | Nocturnal myoclonus (periodic movements in sleep) |

| 1954 | Davison | Pallido-pyramidal syndrome (PARK15) |

| 1956 | Moersch/Woltman | Stiff-person syndrome |

| 1957 | Schonecker | Tardive dyskinesia |

| 1958 | Kirstein/Silfverskiold | Startle disease (hyperekplexia) |

| 1958 | Smith et al. | Dentatorubral-pallidoluysian degeneration |

| 1958 | Monrad-Krohn/Refsum | Myorhythmia |

| 1959 | Paulson | Acute dystonic reaction |

| 1960 | Ekbom | Restless legs |

| 1960 | Shy/Drager | Dysautonomia with parkinsonism (multiple system atrophy) |

| 1961 | Hirano et al. | Parkinsonism-dementia complex of Guam |

| 1961 | Andermann et al. | Facial myokymia |

| 1961 | Isaacs | Neuromyotonia, Isaacs syndrome |

| 1962 | Kinsbourne | Opsoclonus-myoclonus |

| 1963 | Lance/Adams | Posthypoxic action myoclonus |

| 1964 | Adams et al. | Striatonigral degeneration |

| 1964 | Steele et al. | Progressive supranuclear palsy |

| 1964 | Levine | Neuroacanthocytosis |

| 1964 | Kinsbourne | Sandifer syndrome |

| 1964 | Lesch/Nyhan | Lesch–Nyhan syndrome |

| 1965 | Hakim/Adams | Normal pressure hydrocephalus |

| 1965 | Goldstein/Cogan | Apraxia of lid opening |

| 1966 | Suhren et al. | Hyperekplexia |

| 1966 | Rett | Rett syndrome |

| 1967 | Haerer et al. | Hereditary nonprogressive chorea |

| 1968 | Rebeiz et al. | Cortical-basal ganglionic degeneration |

| 1968 | Delay/Denniker | Neuroleptic malignant syndrome |

| 1969 | Horner/Jackson | Hypnogenic paroxysmal dyskinesias |

| 1969 | Graham/Oppenheimer | Multiple system atrophy |

| 1970 | Spiro | Minipolymyoclonus |

| 1970 | Ritchie | Jumpy stumps |

| 1971 | Spillane et al. | Painful legs and moving toes |

| 1975 | Perry et al. | Familial parkinsonism with hypoventilation and mental depression |

| 1976 | Segawa et al. | Dopa-responsive dystonia |

| 1976 | Allen/Knopp | Dopa-responsive dystonia |

| 1977 | Hallett et al. | Reticular myoclonus |

| 1978 | Satoyoshi | Satoyoshi syndrome |

| 1978 | Fahn | Tardive akathisia |

| 1979 | Hallett et al. | Cortical myoclonus |

| 1979 | Rothwell et al. | Primary writing tremor |

| 1980 | Fukuhara et al. | Myoclonus epilepsy associated with ragged red fibers (MERFF) |

| 1980 | Coleman et al. | Periodic movements in sleep |

| 1981 | Fahn/Singh | Oscillatory myoclonus |

| 1981 | Lugaresi/Cirignotta | Hypnogenic paroxysmal dystonia |

| 1982 | Burke et al. | Tardive dystonia |

| 1983 | Langston et al. | MPTP-induced parkinsonism |

| 1984 | Heilman | Orthostatic tremor |

| 1985 | Aronson | Breathy dysphonia |

| 1986 | Bressman et al. | Biotin-responsive myoclonus |

| 1986 | Schenck et al. | REM sleep behavior disorder |

| 1986 | Schwartz et al. | Oculomasticatory myorhythmia |

| 1987 | Tominaga et al. | Tardive myoclonus |

| 1987 | Little/Jankovic | Tardive myoclonus |

| 1990 | Iliceto et al. | Abdominal dyskinesias |

| 1990 | Ikeda et al. | Cortical tremor/myoclonus |

| 1991c | Brown et al. | Propriospinal myoclonus |

| 1991 | Hymas et al. | Obsessional slowness |

| 1991 | De Vivo et al. | GLUT1 deficiency syndrome |

| 1992 | Stacy/Jankovic | Tardive tremor |

| 1993 | Bhatia et al. | Causalgia-dystonia |

| 1993 | Atchison et al. | Primary freezing gait |

| 1993 | Achiron et al. | Primary freezing gait |

| 2002 | Namekawa et al. | Adult-onset Alexander disease |

| 2002 | Okamoto et al. | Adult-onset Alexander disease |

Other important dates in the history of movement disorders are 1912, the coining of the term “extrapyramidal” by Wilson; 1985, the founding of the Movement Disorder Society, and 1986, the publication of the first issue of the journal, Movement Disorders.

Epidemiology

Movement disorders are common neurologic problems, and epidemiological studies are available for some of them (Table 1.3). There have been several studies for Parkinson disease (PD), and these have been carried out in several countries (Tanner, 1994; de Lau and Breteler, 2006). Table 1.3 lists the prevalence rates of some movement disorders based on studies in the United States. The frequency of different types of movement disorders seen in the two specialty clinics at Columbia University and Baylor College of Medicine are presented in Table 1.4. More detailed information is provided in the relevant chapters for specific diseases.

| Disorder | Rate per 100 000 | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Restless legs | 9800* | Rothdach et al. (2000) |

| Essential tremor | 415 | Haerer et al. (1982) |

| Parkinson disease | 187† | Kurland (1958) |

| Tourette syndrome | 29–1052 | Caine et al. (1988), Comings et al. (1990) |

| 2990 | Mason et al. (1998) | |

| Primary torsion dystonia | 33 | Nutt et al. (1988) |

| Hemifacial spasm | 7.4–14.5 | Auger and Whisnant (1990) |

| Blepharospasm | 13.3 | Defazio et al. (2001) |

| Hereditary ataxia | 6 | Schoenberg (1978) |

| Huntington disease | 2–12 | Harper (1992), Kokmen et al. (1994) |

| Wilson disease | 3 | Reilly et al. (1993) |

| Progressive supranuclear palsy | 2 | Golbe (1994) |

| 2.4 | Nath et al. (2001) | |

| 6.4 | Schrag et al. (1999) | |

| Multiple system atrophy | 4.4 | Schrag et al. (1999) |

Rates are given per 100 000 population. *For restless legs, the rate cited is in a population 65–83 years of age. †For Parkinson disease, the rate is 347 per 100 000 for ages over 39 years (Schoenberg et al., 1985).

Table 1.4 The prevalence of movement disorders encountered in two large movement disorder clinics

| Movement disorder | Number of patients | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Parkinsonism | 15 107 | 35.3 |

| Parkinson disease | 10 182 | |

| Progressive supranuclear palsy | 750 | |

| Multiple system atrophy | 841 | |

| Cortical-basal ganglionic degeneration | 297 | |

| Vascular | 867 | |

| Drug-induced | 327 | |

| Hemiparkinsonism–hemiatrophy | 116 | |

| Gait disorder | 329 | |

| Other | 1 308 | |

| Dystonia | 10 394 | 24.3 |

| Primary dystonia | 7 784 | |

| Focal | (59%) | |

| Segmental | (29%) | |

| Generalized | (12%) | |

| Secondary dystonia | 6 610 | |

| Hemidystonia | 279 | |

| Tardive | 595 | |

| Other | 1 737 | |

| Tremor | 6 754 | 15.8 |

| Essential tremor | 2 818 | |

| Cerebellar | 205 | |

| Midbrain (“rubral”) | 88 | |

| Primary writing | 114 | |

| Orthostatic | 82 | |

| Other | 1 035 | |

| Tics (Tourette syndrome) | 2 753 | 6.4 |

| Chorea | 1 225 | 2.9 |

| Huntington disease | 690 | |

| Hemiballism | 123 | |

| Other | 412 | |

| Tardive syndromes | 1 253 | 2.9 |

| Myoclonus | 1 020 | 2.4 |

| Hemifacial spasm | 693 | 1.6 |

| Ataxia | 764 | 1.9 |

| Paroxysmal dyskinesias | 474 | 1.1 |

| Stereotypies (other than TD) | 246 | 0.6 |

| Restless legs syndrome | 807 | 1.9 |

| Stiff-person syndrome | 70 | 0.2 |

| Psychogenic movement disorder | 1 268 | 3.0 |

| Grand total | 42 826 | 100 |

The above data were obtained from the combined databases of the Movement Disorder Clinics at Columbia University Medical Center (New York City) and Baylor College of Medicine (Houston) for patients encountered through April 2009. Because some patients might have more than one type of movement disorder (such as a combination of essential tremor and Parkinson disease), they would be listed more than once. Therefore, the figures in the table represent the types of movement disorder phenomenology encountered in two large clinics, rather than the exact number of patients.

Genetics

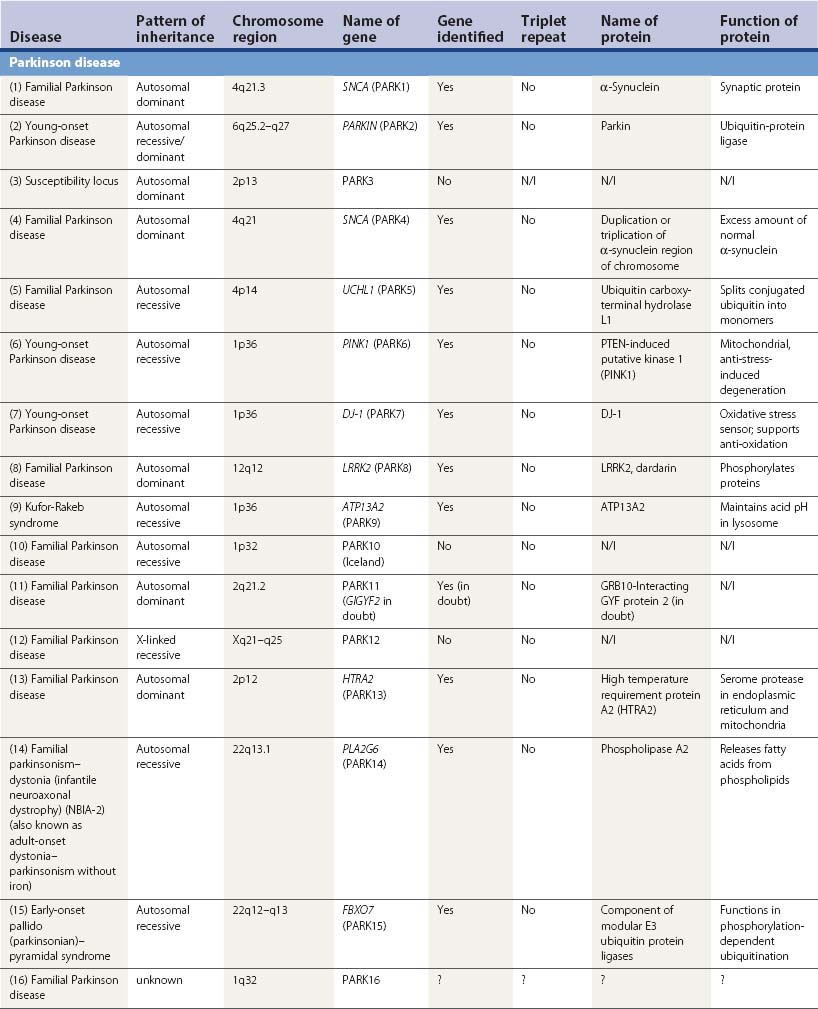

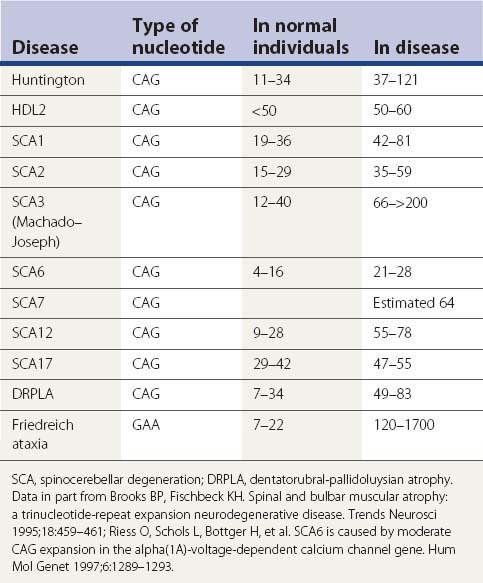

A large number of movement disorders are genetic in etiology, and many of the diseases have now been mapped to specific regions of the genome, and some have even been localized to a specific gene (Table 1.5). For example, ten genetic loci have so far been identified with Parkinson disease (PD) or variants of classic PD (PARK4 is a triplication of the normal α-synuclein gene, for which mutations are listed as PARK1). Several genetic loci of movement disorders have been identified with a specific gene and protein. A comprehensive list of movement disorders whose genes have been mapped or identified are listed in Table 1.5. A detailed chapter (Harris and Fahn, 2003) and an entire book (Pulst, 2003) have been published specifically related to movement disorder genetics. Several inherited movement disorders are due to expanded repeats of the trinucleotide cytosine-adenosine-guanosine (CAG), and Friedreich ataxia is due to the expanded trinucleotide repeat of guanosine-adenosine-adenosine (GAA). Normal individuals contain an acceptable number of these trinucleotide repeats in their genes, but these triplicate repeats are unstable, and when expanded, lead to disease (Table 1.6). Neurogenetics is one of the fastest moving research areas in neurology, so the list in Table 1.5 keeps expanding rapidly.

Quantitative assessments

The assessment of severity of disease is a process that is carried out by all clinicians when evaluating a patient. Quantifying the severity provides the means of determining the progression of the disorder and the effect of intervention by pharmacologic or surgical approaches. Many mechanical and electronic devices, including accelerometers, can quantitate specific signs, such as tremor, rigidity, and bradykinesia. These have been developed by physicians and engineers over at least 80 years (Lewy, 1923; Carmichael and Green, 1928), and newer computerized devices continue to be conceived and developed (Larsen et al., 1983; Tryon, 1984; Potvin and Tourtelotte, 1985; Cohen et al., 2003). The advantages of mechanical and electronic measurements are objectivity, consistency, uniformity among different investigators, and rapidity of database storage and analysis. However, these measurements might not be as sensitive as more subjective clinical measurements. In one study comparing objective measurements of reaction and movement times with clinical evaluations, Ward and his colleagues (1983) found the latter to be more sensitive.

The mechanical and electronic methods of measurement have other disadvantages. Instrumentation can usually measure only a single sign, at a single point in time, and in a single part of the body. Disorders such as parkinsonism encompass a wide range of motor abnormalities, as well as behavioral features. Clinical measurements can cover a wider range of the parkinsonian spectrum of impairments, and have the advantage of being carried out at the bedside or in the office or clinic at the time the patient is being examined by the physician. Equally important, clinical assessment can evaluate disability in terms of activities of daily living (ADL), and the one developed by England and Schwab (1956) and modified slightly (Fahn and Elton, 1987) has proven highly useful.

A number of clinical rating scales have been proposed (e.g., see Marsden and Schachter, 1981). Several that are now considered standards and are in wide use can be recommended: the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) (Fahn and Elton, 1987) is the standard scale for rating severity of signs and symptoms; a videotaped demonstration of the assigned ratings has been published (Goetz et al., 1995). A modification of the UPDRS by the Movement Disorder Society is underway (Goetz et al., 2007) and will be known as the MDS-UPDRS. Other standard scales for PD and its complications are the Schwab and England Activities of Daily Living scale for parkinsonism (Schwab and England, 1969) as modified (Fahn and Elton, 1987); the Hoehn and Yahr Parkinson Disease Staging Scale (Hoehn and Yahr, 1967) as modified (Fahn and Elton, 1987); the Goetz dopa dyskinesia severity scale (Goetz et al., 1994); the Lang–Fahn dopa dyskinesia ADL scale (Parkinson Study Group, 2001); the Parkinson psychosis scale (Friedberg et al., 1998); the daily diary to record fluctuations and dyskinesias (Hauser et al., 2004); the core assessment program for intracerebral transplantation (Langston et al., 1992); the PSP Rating Scale (Golbe and Ohman-Strickland, 2007); the Fahn–Marsden Dystonia Rating Scale (Burke et al., 1985); the Unified Dystonia Rating Scale (Comella et al., 2003); the Fahn–Tolosa clinical rating scale for tremor (Fahn et al., 1993); the Bain tremor scale (Bain et al., 1993); and the Unified Huntington’s Disease Rating Scale, which also has a published videotaped demonstration of assigned ratings (Huntington Study Group, 1996).

Differential diagnosis of hypokinesias

For a list of hypokinesias, refer to Table 1.1.

Akinesia/Bradykinesia

Akinesia, bradykinesia, and hypokinesia literally mean “absence,” “slowness,” and “decreased amplitude” of movement, respectively. The three terms are commonly grouped together for convenience and usually referred to under the term of bradykinesia. These phenomena are a prominent and most important feature of parkinsonism, and are often considered a sine qua non for parkinsonism. Although akinesia means “lack of movement,” the label is often used to indicate a very severe form of bradykinesia (Video 1.1). Bradykinesia is mild in early PD, and becomes more severe as the disease worsens; similarly in other forms of parkinsonism. A discussion of the phenomenology of akinesia/bradykinesia requires a brief description of the clinical features of parkinsonism. A fuller discussion is presented in Chapter 4. ![]()

Parkinsonism is a neurologic syndrome manifested by any combination of six independent, non-overlapping cardinal motor features: tremor-at-rest, bradykinesia, rigidity, flexed posture, freezing, and loss of postural reflexes (Table 1.7). At least two of these six cardinal features should be present before the diagnosis of parkinsonism is made, one of them being tremor-at-rest or bradykinesia. There are many causes of parkinsonism; they can be divided into four major categories: primary, secondary, parkinsonism-plus syndromes, and heredodegenerative disorders (Table 1.8). Primary parkinsonism (Parkinson disease) is a progressive disorder of unknown etiology or of a known gene defect, and the diagnosis is usually made by excluding other known causes of parkinsonism (Fahn, 1992). The complete classification of parkinsonian disorders is presented in Chapter 4. The specific diagnosis of the type of parkinsonism depends on details of the clinical history, the neurologic examination, and laboratory tests.

Table 1.8 Four categories of parkinsonism

The primary parkinsonism disorder known as Parkinson disease (PD), also referred to as idiopathic parkinsonism, is the most common type of parkinsonism encountered by the neurologist. But drug-induced parkinsonism is probably the most common form of parkinsonism since neuroleptic drugs (dopamine receptor blocking agents), which cause drug-induced parkinsonism, are widely prescribed for treating psychosis (see Chapter 19). Here, some of the motor phenomenology of parkinsonism is discussed as part of the overview of the differential diagnosis of movement disorders based on phenomenology.

Akinesia/bradykinesia/hypokinesia is manifested cranially by masked facies (hypomimia), decreased frequency of blinking, impaired upgaze, impaired ocular convergence, soft speech (hypophonia), loss of inflection (aprosody), and drooling of saliva due to decreased spontaneous swallowing (Video 1.5). When examining cranial structures, one should look for other signs of PD or parkinsonism-plus syndromes. Repetitive tapping of the glabella often reveals non-suppression of blinking (Myerson sign) in patients with PD (Brodsky et al., 2004) (Video 1.6), whereas blinking is normally suppressed after two or three blinks (Brodsky et al., 2004). Eyelid opening after the eyelids were forcefully closed is usually normal in PD, but may be markedly impaired in progressive supranuclear palsy; this has been called “apraxia of eyelid opening” (Video 1.7) even though apraxia is a misnomer. The eyes looking straight ahead are typically quiet in PD, but in some parkinsonism-plus syndromes, square wave jerks may be seen, especially in progressive supranuclear palsy (Video 1.8). Ocular movements are usually normal in PD, except for impaired upgaze and convergence. When saccadic eye movements are impaired, and especially when downgaze is impaired, a parkinsonism-plus syndrome such as progressive supranuclear palsy or cortical-basal ganglionic degeneration is usually indicated (Video 1.9). ![]()

Bradykinesia encompasses a loss of automatic movements as well as slowness in initiating movement on command and reduction in amplitude of the voluntary movement. An early feature of reduction of amplitude is the decrementing of the amplitude with repetitive finger tapping or foot tapping (Video 1.10), which is also manifested by impaired rhythm of the tapping. Decreased rapid successive movements both in amplitude and speed are characteristic of bradykinesia regardless of the etiology of parkinsonism (Video 1.11). Carrying out two activities simultaneously is impaired (Schwab et al., 1954), and this difficulty may be a manifestation of bradykinesia (Fahn, 1990). With the stimulation of a sufficient sensory input, bradykinesia, hypokinesia, and akinesia can be temporarily overcome (kinesia paradoxica) (Video 1.12). ![]()

As the disease advances, the patient begins to assume a flexed posture, particularly of the neck, thorax, elbows, hips, and knees. The patient begins to walk with the arms flexed at the elbows and the forearms placed in front of the body, and with decreased armswing. With the knees slightly flexed, the patient tends to shuffle the feet, which stay close to the ground and are not lifted up as high as they would be in normal motion; with time there is loss of heel strike, which would normally occur when the foot moving forward is placed onto the ground. Eventually the flexion can become extreme (Video 1.14), leading to camptocormia (Azher and Jankovic, 2005) or pronounced kyphoscoliosis with truncal tilting. ![]()

Loss of postural reflexes occurs later in the disease. The patient has difficulty righting himself or herself after being pulled off balance. A simple test (the “pull test”) for the righting reflex is for the examiner to stand behind the patient and give a firm tug on the patient’s shoulders towards the examiner, explaining the procedure in advance and directing that the patient should try to maintain his balance by taking a step backwards (Munhoz et al., 2004; Hunt and Sethi, 2006). Typically, after a practice pull, a normal person can recover within two steps (Video 1.15). A mild loss of postural reflexes can be detected if the patient requires several steps to recover balance. A moderate loss is manifested by a greater degree of retropulsion. With a more severe loss the patient would fall if not caught by the examiner (Video 1.16), who must always be prepared for such a possibility. With a marked loss of postural reflexes a patient cannot withstand a gentle tug on the shoulders or cannot stand unassisted without falling. To avoid having the patient fall to the ground, it is wise to have a wall behind the examiner, particularly if the patient is a large or bulky individual. ![]()

In addition to these motor signs, most patients with PD have behavioral signs. Bradyphrenia is mental slowness, analogous to the motor slowness of bradykinesia. Bradyphrenia is manifested by slowness in thinking or in responding to questions. It occurs even at a young age in PD and is more common than dementia. The “tip-of-the-tongue” phenomenon (Matison et al., 1982), in which a patient cannot immediately come up with the correct answer but knows what it is, may be a feature of bradyphrenia. With time the parkinsonian patient gradually becomes more passive, indecisive, dependent, and fearful. The spouse gradually makes more of the decisions and becomes the dominant voice. Eventually, the patient would sit much of the day unless encouraged to do activities. Passivity and lack of motivation also express themselves by the patient’s not desiring to attend social events. The term abulia is used to describe such apathy, loss of mental and motor drive, and blunting of emotional, social, and motor expression. Abulia encompasses loss of spontaneous and responsive motor activity and loss of spontaneous affective expression, thought, and initiative.

Depression is a frequent feature in patients with PD, being obvious in around 30% of cases. The prevalence of dementia in PD is about 40%, but the proportion increases with age. Below the age of 60 years, the proportion with dementia is about 8%; older than 80 years, it is 69% (Mayeux et al., 1992). Following PD patients over time, about 80% develop dementia (Aarsland et al., 2003; Buter et al., 2008). The risk of death is markedly increased when a PD patient becomes demented (Marder et al., 1991).

The age at onset of PD is usually above the age of 40, but younger patients can be affected. Onset between ages 20 and 40 is called young-onset Parkinson disease; onset before age 20 is called juvenile parkinsonism. Juvenile parkinsonism does not preclude a diagnosis of Parkinson disease, but it raises questions of other etiologies, such as Wilson disease (Video 1.5) and the Westphal variant of Huntington disease (Video 1.11). Also familial and sporadic primary juvenile parkinsonism might not show the typical pathologic hallmark of Lewy bodies (Dwork et al., 1993). One needs to be aware when reading the literature that in Japan, onset before age 40 is called juvenile parkinsonism and that some research studies have called onset by age 50 young-onset.

PD is more common in men, with a male:female ratio of 3 : 2. The incidence in the United States is 20 new cases per 100,000 population per year (Schoenberg, 1987), with a prevalence of 187 cases per 100 000 population (Kurland, 1958). For the population over 40 years of age, the prevalence rate is 347 per 100 000 (Schoenberg et al., 1985). With the introduction of levodopa the mortality rate dropped from 3-fold to 1.5-fold above normal. But after the first wave of impaired patients becoming improved with this new and effective treatment, the mortality rate for PD gradually climbed back to the pre-levodopa rate (Clarke, 1995).

Apraxia

Apraxia is a cerebral cortex, not a basal ganglia, dysfunction. Apraxia is traditionally defined as a disorder of voluntary movement that cannot be explained by weakness, spasticity, rigidity, akinesia, sensory loss, or cognitive impairment. It can exist and be tested for in the presence of a movement disorder provided that akinesia, rigidity, or dystonia is not so severe that voluntary movement cannot be executed. The classic work of Liepmann (1920) defined three categories of apraxia.

The concepts of apraxia are being refined into more discrete identifiable syndromes as knowledge of the functions of the cortical systems controlling voluntary movement advances (for reviews, see Pramstaller and Marsden, 1996; Zadikoff and Lang, 2005). A quick, convenient method for testing for apraxia at the bedside is to ask the patients to copy a series of hand postures shown to them by the examiner.

Ideomotor and limb-kinetic apraxias are found in a number of movement disorders – for example, cortical-basal ganglionic degeneration (CBGD) (Video 1.19) and progressive supranuclear palsy (see Chapter 9). A number of other phenomena reflecting cerebral cortex dysfunction may be seen in such patients. Patients with CBGD frequently have signs of cortical myoclonus (Video 1.20) or cortical sensory deficit. The alien limb phenomenon, also seen in CBGD, consists of involuntary, spontaneous movements of an arm or leg (Video 1.21), which curiously and spontaneously moves to adopt odd postures quite beyond the control or understanding of the patient. Intermanual conflict is another such phenomenon; one hand irresistibly and uncontrollably begins to interfere with voluntary action of the other. The abnormally behaving limb may also show forced grasping of objects, such as blankets or clothing. Such patients often exhibit other frontal lobe signs, such as a grasp reflex or utilization behavior, in which they compulsively pick up objects presented to them and begin to use them. For example, if a pen is presented with no instructions, they pick it up and write. If a pair of glasses is proffered, they place the glasses on the nose; if further pairs of glasses are then shown, the patient may end up with three or more spectacles on the nose! ![]()

Cataplexy and drop attacks

Drop attacks can be defined as sudden falls with or without loss of consciousness, due either to collapse of postural muscle tone or to abnormal muscle contractions in the legs. About two-thirds of cases are of unknown etiology (Meissner et al., 1986). Symptomatic drop attacks have many neurologic and non-neurologic causes. Neurologic disorders include leg weakness, sudden falls in parkinsonian syndromes including those due to freezing, transient ischemic attacks, epilepsy, myoclonus, startle reactions (hyperekplexia), paroxysmal dyskinesias, structural central nervous system lesions, and hydrocephalus. In some of these, there is loss of muscle tone in the legs, in others there is excessive muscle stiffness with immobility, such as in hyperekplexia. Syncope and cardiovascular disease account for non-neurologic causes. Idiopathic drop attacks usually appear between the ages of 40 and 59 years, the prevalence increasing with advancing age (Stevens and Matthews, 1973), and are a common cause of falls and fractures in elderly people (Sheldon, 1960; Nickens, 1985). A review of drop attacks has been provided by Lee and Marsden (1995).

Cataplexy is another cause of symptomatic drop attacks that does not fit the categories listed previously. Patients with cataplexy fall suddenly without loss of consciousness but with inability to speak during an attack. There is a precipitating trigger, usually laughter or a sudden emotional stimulus. The patient’s muscle tone is flaccid and remains this way for many seconds. Cataplexy is usually just one feature of the narcolepsy syndrome; other features include sleep paralysis and hypnagogic hallucinations, in addition to the characteristic feature of sudden, uncontrollable falling asleep. A review of cataplexy has been provided by Guilleminault and Gelb (1995).

Catatonia, psychomotor depression, and obsessional slowness

In 1874, Karl Ludwig Kahlbaum wrote the following description: “the patient remains entirely motionless, without speaking, and with a rigid, mask like facies, the eyes focused at a distance; he seems devoid of any will to move or react to any stimuli; there may be fully developed ‘waxen’ flexibility, as in cataleptic states, or only indications, distinct, nevertheless, of this striking phenomenon. The general impression conveyed by such patients is one of profound mental anguish” (Bush et al., 1996).

Gelenberg (1976) defined catatonia as a syndrome characterized by catalepsy (abnormal maintenance of posture or physical attitudes), waxy flexibility (retention of the limbs for an indefinite period of time in the positions in which they are placed), negativism, mutism, and bizarre mannerisms. Patients with catatonia can remain in one position for hours and move exceedingly slowly to commands, usually requiring the examiner to push them along (Video 1.23). But, when moving spontaneously, they move quickly, such as when scratching themselves. In contrast to patients with parkinsonism, there is no concomitant cogwheel rigidity, freezing, or loss of postural reflexes. Classically, catatonia is a feature of schizophrenia, but it can also occur with severe depression. Gelenberg also stated that catatonia can appear with conversion hysteria, dissociative states, and organic brain disease. However, we believe that his organic syndromes of akinetic mutism, abulia, encephalitis, and so forth should be distinguished from catatonia, and catatonia should preferably be considered a psychiatric disorder. ![]()

Some patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) may present with extreme slowness of movement, so-called obsessional slowness. Hymas and colleagues (1991) evaluated 17 such patients out of 59 admitted to hospital with OCD. These patients had difficulty initiating goal-directed action and had many suppressive interruptions and perseverative behaviors. Besides slowness, some patients had cogwheel rigidity, decreased armswing when walking, decreased spontaneous movement, hypomimia, and flexed posture. However, there was no decrementing of either amplitude or speed with repetitive movements, no tremor, and no micrographia. Also there was no freezing or loss of postural reflexes. Like other cases of OCD, this is a chronic illness. Fluorodopa positron emission tomography scans revealed no abnormality of dopa uptake, thereby clearly distinguishing this disorder from PD (Sawle et al., 1991). However, there is hypermetabolism in orbital, frontal, premotor, and midfrontal cortex, suggesting excessive neural activity in these regions.

Freezing

Freezing refers to transient periods, usually lasting several seconds, in which the motor act is halted, being stuck in place. It commonly develops in parkinsonism (see Chapter 4), both primary and atypical parkinsonism (Giladi et al., 1997), and it is one of its six cardinal signs. The freezing phenomenon has also been called motor blocks (Giladi et al., 1992). The terms pure akinesia (Narabayashi et al., 1976, 1986; Imai et al., 1986), and gait ignition failure (Atchison et al., 1993; Nutt et al., 1993) refer to syndromes in which freezing is the predominant clinical feature with only a few other features of parkinsonism.

In freezing there can be several different phenomena. One is no apparent attempt to move. Another is that the voluntary motor activity being attempted is halted because agonist and antagonist muscles are simultaneously and isometrically contracting (Andrews, 1973), preventing normal execution of voluntary movement. The motor blockage in this circumstance, therefore, is not one of lack of muscle activity, but rather is analogous to being glued to a position so that the patient exerts increased effort to overcome being “stuck.” The stuck body part attempts to move to overcome the block, and muscle force (isometric) is being exerted. So, with freezing of gait, by far the most common form of the freezing phenomenon, as the patient attempts to move the feet, short, incomplete steps are attempted, but the feet tend to remain in the same place (“glued to the ground”). After a few seconds, the freezing clears spontaneously, and the patient is able to move at his or her normal pace again until the next freezing episode develops. Often, the patient has learned some trick maneuver to terminate the freezing episode sooner (Videos 1.25 and 1.26). Stepping over an inverted cane when the legs begin to freeze is one method by which patients can manage to ambulate (Video 1.27). ![]()

Although freezing most often affects walking, it can manifest in other ways (Table 1.9). Speech can be arrested with the patient repeating a sound until it finally becomes unstuck, and speech then continues (Video 1.28). This can be considered a severe form of parkinsonian palilalia, which usually refers to a repetition of the first syllable of the word the patient is trying to verbally express. Parkinsonian palilalia differs from the palilalia seen in patients with Gilles de la Tourette syndrome, in which there is repetition of entire words or a string of words (see Video 1.22). ![]()

Freezing of the arms, such as during handwriting or teeth-brushing, has also been reported (Narabayashi et al., 1976). Difficulty opening the eyes can be another example of freezing (see Video 1.7). This eyelid freezing was originally called apraxia of eyelid opening, which is a misnomer because the problem is not an apraxia. Eyelid freezing has also been called “levator palpebrae inhibition” (Lepore and Duvoisin, 1985) and even a form of dystonia. Although previously unrecognized as a freezing phenomenon and usually considered a form of body bradykinesia, difficulty in rising from a chair may be due to freezing in some patients (see Video 1.25). Patients use many tricks to overcome freezing, but these might not always be successful. A discourse on the freezing phenomenon is provided in a review by Fahn (1995). ![]()

As was discussed previously, the freezing phenomenon occurs in parkinsonism, whether it be primary (PD) (Giladi et al., 1992), secondary (such as vascular parkinsonism), or parkinsonism-plus syndromes, such as progressive supranuclear palsy and multiple system atrophy. It can also appear as an idiopathic freezing gait without other features of parkinsonism, except for loss of postural reflexes and mild bradykinesia (Achiron et al., 1993; Atchison et al., 1993) (Video 1.29). In some patients, it may be an early sign of impending progressive supranuclear palsy (Riley et al., 1994) or due to nigropallidal degeneration (Katayama et al., 1998). ![]()

Hesitant gaits

Hesitant gaits or uncertain gaits are seen in a number of syndromes (see Chapter 10). The cautious gait that is seen in some elderly people is slow on a wide base with short steps and superficially may resemble that of parkinsonism except that there are no other parkinsonian features. Fear of falling, because of either perceived instability or realistic loss of postural righting reflexes, produces an inability to walk independently without holding onto people or objects. Because this abnormal gait disappears when the person walks holding onto someone, it is often considered to be a psychiatric disorder, a phobia of open spaces (i.e., agoraphobia). But because previous falls usually play a role in patients developing this disorder, it appears to be a true fear of falling that is distinguishable from agoraphobia, which is a separate syndrome. Fear of falling (a psychiatric gait disorder) should be differentiated from psychogenic gait disorders (see Chapter 25). A cautious gait, such as in fear of falling, may be superimposed on any other gait disorder.

The senile gait disorder (or gait disorder of the elderly) is a poorly understood condition that comprises a number of different syndromes (Nutt et al., 1993). In gait ignition failure (Atchison et al., 1993), also called primary freezing gait (Achiron et al., 1993), the problem is one of getting started. Once underway, such patients walk fairly briskly (see Video 1.29), and equilibrium is preserved. In frontal gait disorders, there is also start-hesitation, and walking is with slow, small, shuffling steps, similar to that in PD. However, there are few other signs of parkinsonism, and equilibrium is preserved. Such a gait can occur with frontal lobe tumors, cerebrovascular disease, and hydrocephalus, all causing frontal lobe damage. This pattern has been incorrectly called frontal ataxia or gait apraxia in the older literature. ![]()

Other hesitant gaits are those due to severe disequilibrium. These types of gait have been associated with frontal cortex and deep white matter lesions (frontal disequilibrium) or thalamic and midbrain lesions (subcortical disequilibrium) (Nutt et al., 1993). Hesitant gait syndromes are covered in more depth in Chapter 10.

Rigidity

Rigidity is characterized as increased muscle tone to passive motion. It is distinguished from spasticity in that it is present equally in all directions of the passive movement, equally in flexors and extensors, and throughout the range of motion, and it does not exhibit the clasp-knife phenomenon, nor increased tendon reflexes. Rigidity can be smooth (lead-pipe) or jerky (cogwheel). Cogwheeling occurs in the same range of frequencies as action and resting tremor (Lance et al., 1963) and appears to be due to superimposition of a tremor rhythm (Denny-Brown, 1962). Cogwheel rigidity is more common than the lead-pipe variety in parkinsonism (nigral lesion), and lead-pipe rigidity can be caused by a number of other central nervous system lesions (Fahn, 1987), including those involving the corpus striatum (hypoxia, vascular, neuroleptic malignant syndrome), cortical-basal (ganglionic degeneration) (Video 1.30), midbrain (decorticate rigidity), medulla (decerebrate rigidity), and spinal cord (tetanus). When a patient does not thoroughly relax to allow passive manipulation of his/her joints, but tends to actively resist, the result is increased muscle tone, so-called Gegenhalten. Gegenhalten is commonly seen in patients with impaired cognition. Often, with Gegenhalten, more force applied by the examiner is met with more resistance by the patient. ![]()

Rigidity is one part of the neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) (see Chapter 19), which is an idiosyncratic adverse effect of dopamine receptor blocking agents, usually antipsychotic drugs (Smego and Durack, 1982; Kurlan et al., 1984), but it has also been reported to occur on sudden discontinuation of levodopa therapy (Friedman et al., 1985; Keyser and Rodnitzky, 1991). The clinical features of the syndrome are the abrupt onset of a combination of rigidity/dystonia, fever with other autonomic dysfunctions such as diaphoresis and dyspnea, and an altered mental state including confusion, stupor, or coma. The level of serum creatine kinase activity is usually elevated. The dopamine receptor blocking agents may have been administered at therapeutic, not toxic, dosages. There does not seem to be any relationship with the duration of therapy. It can develop soon after the first dose or anytime after prolonged treatment. This is a potentially lethal disorder unless treated; up to 25% of patients die (Henderson and Wooten, 1981). NMS is sometimes called malignant catatonia (Boeve et al., 1994), and needs to be distinguished from malignant hyperthermia.

Stiff muscles

Stiff muscles are defined as being due to continuous muscle firing without muscle disease, and not to rigidity or spasticity. Stiffness syndromes are reviewed in detail in Chapter 11. Briefly, there are four major clinical categories of stiff-muscle syndromes: continuous muscle fiber activity or neuromyotonia, encephalomyelitis with rigidity, the stiff-limb syndrome, and the stiff-person syndrome (Thompson, 1994), with the last three being variations of the same disorder. Neuromyotonia is a syndrome of myotonic failure of muscle relaxation plus myokymia and fasciculations. Clinically it manifests as continuous muscle activity causing stiffness and cramps. The best-known neuromyotonic disorder is Isaacs syndrome (Isaacs, 1961).

Encephalomyelitis with rigidity (Whiteley et al., 1976), initially called spinal interneuronitis, manifests with marked rigidity and muscle irritability, with increased response to tapping the muscles, along with myoclonus (Video 1.31). It is now recognized as a severe manifestation of stiff-person syndrome and may respond to steroid therapy. ![]()

Stiff-person syndrome refers to a rare disorder (Spehlmann and Norcross, 1979) in which many somatic muscles are continuously contracting isometrically, resembling “chronic tetanus,” in contrast to dystonic movements which produce abnormal twisting and patterned movements and postures. The contractions of stiff-person syndrome are usually forceful and painful and most frequently involve the trunk and neck musculature (Video 1.32). The proximal limb muscles can also be involved, but rarely does the disorder first affect the distal limbs. Benzodiazepines and valproate are usually somewhat effective. Withdrawal of these agents results in an increase of painful spasms. This disorder has now been recognized to be an autoimmune disease, with circulating antibodies against the GABA-synthesizing enzyme, glutamic acid decarboxylase, and also other type of antibodies, including antibodies against insulin (Solimena et al., 1988, 1990; Blum and Jankovic, 1991). Diabetes is a common accompanying disorder. The diagnosis can now be aided by laboratory testing for these antibodies. The syndrome of interstitial neuronitis, also called encephalomyelitis with rigidity and myoclonus, is a more acute variant of the stiff-person syndrome. The so-called stiff-baby syndrome (Video 1.33) is actually due to infantile hyperekplexia, in which the muscles continue to fire repeatedly and so frequently that the muscles appear to contract continuously. ![]()

Differential diagnosis of dyskinesias

A list of abnormal involuntary movements is presented alphabetically in Table 1.1 under “Hyperkinesias.” A brief description of each of these is now presented along with its major recognizable and differentiating features. Tables 1.10–1.18 list the ordinary process of distinguishing one type of dyskinesia from another by the major stepwise deciphering based on a practical approach.

Abdominal dyskinesias

Abdominal dyskinesias are continuous movements of the abdominal wall or sometimes the diaphragm. The movements persist, and their sinuous, rhythmic nature has led to their being called belly dancer’s dyskinesia (Iliceto et al., 1990). They may be associated with abdominal trauma in some cases, and a common result is segmental abdominal myoclonus (Kono et al., 1994) (Video 1.34). Another common cause is tardive dyskinesia. Hiccups, which are regularly recurring diaphragmatic myoclonus, do not move the abdomen and umbilicus in a sinewy fashion but with sharp jerks and typically with noises as air is expelled by the contractions, so they should not present a diagnostic problem. Abdominal dyskinesias are discussed in Chapter 23. ![]()

Akathitic movements

Akathisia does not necessarily affect the whole body; an isolated body part can be affected. Focal akathisia often produces a sensation of burning or pain, again relieved by moving that body part. Common sites for focal akathisia/pain are the mouth and vagina (Ford et al., 1994).

Akathisia may be expressed by vocalizations, such as continual moaning, groaning, or humming. Other movement disorders associated with moaning sounds or humming are tics, oromandibular dystonia, Huntington disease, parkinsonian disorders (Micheli et al., 1991; Friedman, 1993), and those induced by levodopa (Fahn et al., 1996).

The most common cause of akathisia is iatrogenic. It is a frequent complication of antidopaminergic drugs, including those that block dopamine receptors (such as antipsychotic drugs and certain antiemetics) and those that deplete dopamine (such as reserpine and tetrabenazine). Akathisia can occur when drug therapy is initiated (acute akathisia), subsequently with the emergence of drug-induced parkinsonism, or after chronic treatment (tardive akathisia). Acute akathisia is eliminated on withdrawal of the medication. Tardive akathisia usually is associated with the syndrome of tardive dyskinesia (see Chapter 19). Like tardive dyskinesia, tardive akathisia is aggravated by discontinuing the neuroleptic, and it is usually relieved by increasing the dose of the offending drug which masks the movement disorder. When associated with tardive dyskinesia, the akathitic movements can be rhythmic, such as body rocking or marching in place. In this situation, it is difficult to be certain whether such rhythmic movements are due to akathisia or to tardive dyskinesia.

Athetosis

Athetosis has been used in two senses: to describe a class of slow, writhing, continuous, involuntary movements, and to describe the syndrome of athetoid cerebral palsy. The latter commonly occurs as a result of injury to the basal ganglia in the prenatal or perinatal period or during infancy. Athetotic movements affect the limbs, especially distally, but can also involve axial musculature, including neck, face, and tongue. When not present in certain body parts at rest, it can often be brought out by having the patient carry out voluntary motor activity elsewhere in the body; this phenomenon is known as overflow. For example, speaking can induce increased athetosis in the limbs, neck, trunk, face, and tongue (Video 1.38). Athetosis often is associated with sustained contractions producing abnormal posturing. In this regard, athetosis blends with dystonia. However, the speed of these involuntary movements can sometimes be faster and blend with those of chorea, and the term choreoathetosis is used. Athetosis resembles “slow” chorea in that the direction of movement changes randomly and in a flowing pattern (see Chapter 15). ![]()

Pseudoathetosis refers to distal athetoid movements of the fingers and toes due to loss of proprioception, which can be due to sensory deafferentation (sensory athetosis) or to central loss of proprioception (Sharp et al., 1994).

Ballism

Ballism refers to very large-amplitude choreic movements of the proximal parts of the limbs, causing flinging and flailing limb movements (see Chapter 15). Ballism is most frequently unilateral, in which case it is referred to as hemiballism (Video 1.39). This is often the result of a lesion in the contralateral subthalamic nucleus or its connections or of multiple small infarcts (lacunes) in the contralateral striatum. In rare instances, ballism occurs bilaterally (biballism) and is due to bilateral lacunes in the basal ganglia (Sethi et al., 1987). Like chorea, ballism can sometimes occur as a result of overdosage of levodopa. ![]()

Chorea

Chorea refers to involuntary, irregular, purposeless, nonrhythmic, abrupt, rapid, unsustained movements that seem to flow from one body part to another. A characteristic feature of chorea is that the movements are unpredictable in timing, direction, and distribution (i.e., random). Although some neurologists erroneously label almost all nonrhythmic, rapid involuntary movements as choreic, many in fact are not. Nonchoreic rapid movements can be tics, myoclonus, and dystonia (see the chapters for each of these disorders); in these conditions, the movements repeat themselves in a set distribution of the body (i.e., are patterned) and do not have the changing, flowing nature of choreic movements, which travel around the body. In rapid dystonic movements, there is a recognizable repetitive recurrence to the movements in the affected body parts, unlike the random nature of chorea. The prototypical choreic movements are those seen in Huntington disease (Video 1.40), in which the brief and rapid movements are irregular and occur randomly as a function of time. In Sydenham chorea and in the withdrawal emergent syndrome (see Chapter 19), the flowing choreic movements have a restless appearance (Video 1.41). ![]()

Choreic movements can be partially suppressed, and the patient can often camouflage some of the movements by incorporating them into semipurposeful movements, known as parakinesia. Chorea is usually accompanied by motor impersistence (“negative chorea”), the inability to maintain a sustained contraction. A common symptom of motor impersistence is the dropping of objects. Motor impersistence is detected by examining for the inability to keep the tongue protruded and by the presence of the “milk-maid” grip due to the inability to keep the fist in a sustained tight grip. For details on choreic disorders, see Chapters 14 and Chapter 15.

Dystonia

Dystonia refers to movements that tend to be sustained at the peak of the movement, are usually twisting and frequently repetitive, and often progress to prolonged abnormal postures (see Chapter 12). In contrast to chorea, dystonic movements repeatedly involve the same group of muscles – that is, they are patterned. Agonist and antagonist muscles contract simultaneously (cocontraction) to produce the sustained quality of dystonic movements. The speed of the movement varies widely from slow (athetotic dystonia) to shocklike (myoclonic dystonia). When the contractions are very brief (e.g., less than a second), they are referred to as dystonic spasms. When they are sustained for several seconds, they are called dystonic movements. When they last minutes to hours, they are known as dystonic postures. When present for weeks or longer, the postures can lead to permanent fixed contractures.

One of the characteristic and almost unique features of dystonic movements is that they can often be diminished by tactile or proprioceptive “sensory tricks” (geste antagoniste). Thus, touching the involved body part or an adjacent body part can often reduce the muscle contractions. Inexperienced clinicians might assume that this sign indicates that the abnormal movements are psychogenic, but the opposite conclusion should be reached, namely that the presence of sensory tricks strongly suggests an organic etiology (Fahn and Williams, 1988). If the dystonia becomes more severe, sensory tricks providing relief tend to diminish.

One type of focal dystonia requires special mention, namely sustained contractions of ocular muscles, resulting in tonic ocular deviation, usually upward gaze (Video 1.50). This is referred to as oculogyric crisis. This sustained ocular deviation was encountered in victims of encephalitis lethargica and later in those survivors who developed postencephalitic parkinsonism. Primary torsion dystonia does not involve the ocular muscles, hence oculogyria is not truly a feature of dystonia syndromes. Oculogyria is more common today as a complication of dopamine receptor blocking agents (Paulson, 1960) as in drug-induced parkinsonism or other parkinsonian syndromes such as juvenile parkinsonism and the parkinsonism associated with the degenerative disease known as neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease (Kilroy et al., 1972; Funata et al., 1990), and with the biochemical deficiency of the monoamines in the metabolic disorders of aromatic amino acid decarboxylase deficiency (Hyland et al., 1992; Chang et al., 2004) and pterin deficiencies (Hyland et al., 1998). There has been a case report of oculogyric crises in a patient with dopa-responsive dystonia (Lamberti et al., 1993) and its phenocopy, tyrosine hydroxylase deficiency. Paroxysmal tonic upgaze has also been seen in infants and children and often eventually subsides (Ouvrier and Billson, 1988), but it may be a forerunner of developmental delay, intellectual disability, or language delay, indicating impaired corticomesencephalic control of vertical eye movements (Hayman et al., 1998). ![]()

Although classic torsion dystonia may appear initially only as an action dystonia, it usually progresses to manifest as continual contractions. A rarer presentation is when primary dystonia appears initially at rest, and then clears when the affected body part or some other part of the body is voluntarily active; this type has been called paradoxical dystonia (Fahn, 1989) (Video 1.52). In contrast to this continual type of classic torsion dystonia, a variant of dystonia also exists in which the movements occur in attacks, with a sudden onset and limited duration – known as paroxysmal dyskinesias (see later in this chapter and also Chapter 22). These are categorized among the paroxysmal disorders. Among the other disorders to be differentiated from dystonia are conditions appearing as sustained contractions; these are tonic tics (also called dystonic tics) (see Chapter 16) and conditions referred to as pseudodystonias (see Chapter 12). ![]()

Hemifacial spasm

Hemifacial spasm, as the name indicates, refers to unilateral facial muscle contractions. Generally these are continual rapid, brief, repetitive spasms (clonic form of hemifacial spasm), but they can also be more prolonged sustained tonic spasms (tonic form), mixed with periods of quiescence (Video 1.53). Often the movements can be brought out when the patient voluntarily and forcefully contracts the facial muscles; when the patient then relaxes the face, the involuntary movements appear. Hemifacial spasm usually affects both upper and lower parts of the face, but patients are commonly more concerned about closure of the eyelid than about the contractions of the cheek or at the corner of the mouth. The eyebrow tends to elevate with the facial contractions owing to being pulled upwards by the forehead muscles. The disorder involves the facial nerve, and often it is due to compression of the nerve by an aberrant blood vessel (Jannetta, 1982). Hemifacial spasm is an example of a peripherally induced movement disorder (see Chapter 23). ![]()

Hyperekplexia and jumping disorders

Hyperekplexia (“startle disease”) is an excessive startle reaction to a sudden, unexpected stimulus (Andermann and Andermann, 1986; Brown et al., 1991b; Matsumoto and Hallett, 1994). The startle response can be either a short “jump” or a more prolonged tonic spasm causing falls (Video 1.54). This condition can be familial or sporadic. If patients have a delayed reaction to sudden noise or threat, a psychogenic problem should be considered (Thompson et al., 1992). ![]()

Startle syndromes may encompass jumping disorders and other similar conditions, with names like Jumping Frenchmen of Maine, latah, myriachit, and Ragin’ Cajun, but all of these appear to be influenced by social and group behavior. The names were coined for the ethnic groups in different parts of the world, although their clinical features are similar. In jumping disorders, after the initial jump to the unexpected stimulus, there is automatic speech or behavior, such as striking out. In some of these, there is automatic obedience to words such as “jump” or “throw” (Matsumoto and Hallett, 1994). Such automatic behaviors are not seen in hyperekplexia. The startle disorders are discussed in more detail in Chapter 20.

Hypnogenic dyskinesias: periodic movements in sleep and REM sleep behavior disorder

Most dyskinesias disappear during deep sleep, although they may emerge during light sleep. The major exception is symptomatic rhythmical oculopalatal myoclonus, which persists during sleep, in addition to being present while the patient is awake (Deuschl et al., 1990). There are, however, a few movement disorders that are present only when the patient is asleep. The most common hypnogenic dyskinesia is the condition known as periodic movements in sleep (Coleman et al., 1980; Lugaresi et al., 1983, 1986; Hening et al., 1986), formerly referred to as nocturnal myoclonus (Symonds, 1953). The latter term is unacceptable because the movements are not shocklike, but, in fact, are rather slow. They appear as flexor contractions of one or both legs, with dorsiflexion of the big toe and the foot, and flexion of the knee and hip (Video 1.55). They occur in intervals, approximately every 20 seconds, and hence have been given its new, more acceptable name (Coleman et al., 1980). Periodic movements in sleep are a frequent component of the restless legs syndrome (see Chapter 23). In addition to periodic movements in sleep, this syndrome also is associated with myoclonic-like and dystonic-like movements during sleep and while the patient is drowsy (Hening et al., 1986). ![]()

Sleep with rapid eye movements (REM sleep) is the stage of sleep in which dreaming occurs. Along with the ocular movements, there is atonia of the other somatic muscles in the body; this permits people to remain free of body movements when they dream. REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD), described by Schenck and colleagues (1986), is a condition in which there is lack of somatic muscle atonia, thus enabling such individuals to move while they dream (acting out their dreams). The affected individual is unaware of these movements unless awakened by falling out of bed or by the bed partner who might have been struck or kicked by the abnormal movements and then awakens the person to stop the movements. RBD may precede by several years the development of a subsequent synucleinopathy (Parkinson disease or multiple system atrophy) (Tan et al., 1996; Postuma et al., 2006; Claassen et al., 2010). RBD may instead develop after the onset of the synucleinopathy, and not all individuals with RBD will develop a synucleinopathy (Postuma et al., 2009).

Another rare nocturnal dyskinesia is hypnogenic paroxysmal dystonia or other dyskinesias that occur only during sleep (Video 1.56) (see Chapter 22). Hypnogenic dystonia can be complex and with sustained contractions, similar to those occurring in torsion dystonia. As its name suggests, such movements occur as a paroxysm during sleep and last only a few minutes. They might or might not awaken the patient. Some may be frontal lobe seizures (Fish and Marsden, 1994). ![]()

Jumpy stumps

Jumpy stumps are uncontrollable and sometimes exhausting chaotic movements of the stump remaining from an amputated limb (Video 1.57). When they occur, it is after a delayed period of time following the amputation (Marion et al., 1989). ![]()

Moving toes and fingers

The painful legs, moving toes syndrome (see Chapter 23) refers to a disorder in which the toes of one foot or both feet are in continual flexion–extension with some lateral motion, associated with a deep pain in the ipsilateral leg (Spillane et al., 1971). The constant movement has a sinusoidal quality (Video 1.58). The movements and pain are continuous, and both occur even during sleep, though they may be reduced and the normal sleep pattern may be altered (Montagna et al., 1983). The leg pain is much more troublesome to the patient than are the constant movements. In most patients with this disorder, there is evidence for a lesion in the lumbar roots or in the peripheral nerves (Nathan, 1978; Montagna et al., 1983; Dressler et al., 1994). An analogous disorder, “painful arm, moving fingers,” has also been described (Verhagen et al., 1985) (Video 1.59). ![]()

Myoclonus

Myoclonic jerks are sudden, brief, shocklike involuntary movements caused by muscular contractions (positive myoclonus) or inhibitions (negative myoclonus) (see Chapter 20). The most common form of negative myoclonus is asterixis, which frequently accompanies various metabolic encephalopathies. In asterixis, the brief flapping of the outstretched limbs is due to transient inhibition of the muscles that maintain posture of those extremities (Video 1.60). Unilateral asterixis has been described with focal brain lesions of the contralateral medial frontal cortex, parietal cortex, internal capsule, and ventrolateral thalamus (Obeso et al., 1995). ![]()

Myoclonus can appear when the affected body part is at rest or when it is performing a voluntary motor act, so-called action myoclonus (Video 1.61). Myoclonic jerks are usually irregular (arrhythmic) but can be rhythmical, such as in palatal myoclonus (Video 1.62 and 1.63) or ocular myoclonus (Video 1.64), with a rate of approximately 2 Hz. Rhythmic ocular myoclonus due to a lesion in the dentato-olivary pathway needs to be distinguished from arrhythmic and chaotic opsoclonus or dancing eyes (Video 1.65). Rhythmic myoclonus is typically due to a structural lesion of the brainstem or spinal cord (therefore also called segmental myoclonus), but not all cases of segmental myoclonus are rhythmic, and some types of cortical epilepsia partialis continua can be rhythmic. Oscillatory myoclonus is depicted as rhythmic jerks that occur in a burst and then fade (Fahn and Singh, 1981). Spinal myoclonus (Video 1.66), in addition to presenting as segmental and rhythmical, can also present as flexion axial jerks triggered by a distant stimulus that travels via a slow-conducting spinal pathway, a type that is called propriospinal myoclonus (Brown et al., 1991c). Respiratory myoclonus can be variable and has been called diaphragmatic flutter and diaphragmatic tremor (Espay et al., 2007). ![]()

Cortical reflex myoclonus usually presents as a focal myoclonus and is triggered by active or passive muscle movements of the affected body part (see Video 1.20). It is associated with high-amplitude (“giant”) somatosensory evoked potentials and with cortical spikes that are observed by computerized back averaging, time-locked to the stimulus (Obeso et al., 1985). Spread of cortical activity within the hemisphere and via the corpus callosum can produce generalized cortical myoclonus or multifocal cortical myoclonus (Brown et al., 1991a). Reticular reflex myoclonus (Hallett et al., 1977) is more often generalized or spreads along the body away from the source in the brainstem in a timed-related sequential fashion. ![]()

Action or intention myoclonus is often encountered after cerebral hypoxia–ischemia (Lance–Adams syndrome) and with certain degenerative disorders such as progressive myoclonus epilepsy (Unverricht–Lundborg disease) and progressive myoclonic ataxia (Ramsay Hunt syndrome). Usually action myoclonus is more disabling than rest myoclonus. Negative myoclonus also occurs in the Lance–Adams syndrome, and when it occurs in the thigh muscles when the patient is standing, it manifests as bouncy legs (Video 1.67). In the opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome, originally described by Kinsbourne (1962) and subsequently called both ‘dancing eyes, dancing feet’ and ‘polymyoclonia’ by Dyken and Kolar (1968), the amplitude of the myoclonus is usually very tiny, resembling irregular tremors. Because of the small amplitudes of the continuous, generalized myoclonus, it is preferable to use the term minipolymyoclonus (Video 1.65), a term that was first used by Spiro (1970) to describe small-amplitude movements in childhood spinal muscular atrophy and subsequently used by Wilkins and colleagues (1985) for the type of myoclonus that is seen in primary generalized epileptic myoclonus. ![]()

Myokymia and synkinesis

Myokymia is a fine persistent quivering or rippling of muscles (sometimes called live flesh by patients). The term has evolved since first used (Schultze, 1895), when it described benign fasciculations. Although some may still refer to the benign fasciculations that frequently occur in orbicularis oculi as myokymia, Denny-Brown and Foley (1948) distinguished between myokymia and benign fasciculations on the basis of electromyography (EMG). In myokymia, the EMG reveals regular groups of motor unit discharges, especially doublets and triplets, occurring with a regular rhythmic discharge. Myokymia occurs most commonly in facial muscles. Most facial myokymias are due to pontine lesions, particularly multiple sclerosis (Andermann et al., 1961; Matthews, 1966), and less often due to pontine glioma. When due to multiple sclerosis, facial myokymia tends to abate after weeks or months. When due to a pontine glioma, facial myokymia may persist indefinitely and can be associated with facial contracture (Video 1.68). Myokymia is also a feature of neuromyotonia (see under “Stiff muscles,” earlier in this chapter). Myokymia can persist during sleep. Continuous facial myokymia in multiple sclerosis has been found by magnetic resonance imaging to be caused by a pontine tegmental lesion involving the postnuclear, postgenu portion of the facial nerve (Jacobs et al., 1994). ![]()

Myorhythmia

The term myorhythmia has been used in different ways over time. Herz (1931, 1944) used it to refer to the somewhat rhythmic movements that are sometimes seen in patients with torsion dystonia. Today, these are simply called dystonic movements and are not distinguished between the movements that are repetitive and those that are not. Dystonic myorhythmia should not be confused with dystonic tremor, which strongly resembles other tremors but is due to dystonia. Monrad-Krohn and Refsum (1958) used the term myorhythmia to label what is today called palatal myoclonus or other rhythmic myoclonias. This meaning of the term myorhythmia has also been adopted by Masucci and colleagues (1984). The term could be used to represent a somewhat slow frequency (<3 Hz) and a prolonged, rhythmic or repetitive movement, in which the movement does not have the sharp square wave appearance of a myoclonic jerk. Therefore, it would not be applied to palatal myoclonus. Myorhythmia would also not apply to the sinusoidal cycles of most tremors (parkinsonian, essential, cerebellar) because the frequency of these tremors is faster than that defined for myorhythmia.

The most typical disorder in which the term myorhythmia is applied is in Whipple disease, in which there are slow-moving, repetitive, synchronous, rhythmic contractions in ocular, facial, masticatory, and other muscles, so-called oculofaciomasticatory myorhythmia (Schwartz et al., 1986; Hausser-Hauw et al., 1988; Tison et al., 1992). There is often also vertical supranuclear ophthalmoplegia. Ocular myorhythmia is manifested as continuous, horizontal, pendular, vergence oscillations of the eyes, usually of small amplitude, occurring about every second (Video 1.69). They may be asymmetric and may continue in sleep. They never diverge beyond the primary position. Divergence and convergence are at the same speed. They are not accompanied by pupillary miosis. The movements in the face, jaw, and skeletal muscles are about at the same frequency but may be somewhat quicker and may be more like rhythmic myoclonus (Video 1.70). The abnormal movements of facial and masticatory muscles can also persist in sleep, as is seen also with palatal myoclonus. ![]()

Sometimes the term myorhythmia may be applied to slow, undulating, rhythmic movements of muscles, unrelated to Whipple disease. Perhaps some of these types of movements are part of the spectrum of complex tics, while in others, they may represent psychogenic movements. Myorhythmias are discussed in Chapter 18.

Paroxysmal dyskinesias

The paroxysmal dyskinesias represent various types of dyskinetic movements, particularly choreoathetosis and dystonia, that occur out of the blue and then disappear after being present for seconds, minutes, or hours (see Chapter 22). The patient can remain unaffected for months between attacks, or there can be many attacks per day.

Paroxysmal nonkinesigenic dyskinesia can be hereditary or symptomatic, is triggered by stress, fatigue, caffeine or alcohol, and can last minutes to hours (Video 1.72). It is more difficult to treat than the kinesigenic variety, but it sometimes responds to clonazepam or other benzodiazepines and sometimes to acetazolamide. Paroxysmal nonkinesigenic dyskinesia can be familial or sporadic. Sporadic paroxysmal nonkinesigenic dyskinesia in our experience is more often a psychogenic movement disorder (see Chapter 25), particularly if it is a combination of both paroxysmal and continual dystonias. ![]()

Restless legs

The term restless legs syndrome refers to more than just the phenomenon of restless legs, in which the patient has unpleasant crawling sensations in the legs, particularly when sitting and relaxing in the evening, which then disappear on walking (Ekbom, 1945, 1960). The complete syndrome consists of several parts, in which one or more may be present in any individual. While the unpleasant dysesthesias in the legs are the most common symptom, as was mentioned previously in the discussion on nocturnal dyskinesias, the clinical spectrum may also include periodic movements in sleep (Video 1.55), myoclonic jerks, more sustained dystonic movements, or stereotypic movements that occur while the patient is awake, particularly in the late evening (Walters et al., 1991). Other movement disorders associated with a sensory phenomenon are akathisia (feeling of inner restlessness) and tics (feeling of relief of tension or sensory urges upon producing a tic). The restless legs syndrome is covered in Chapter 23. ![]()

Stereotypy

Stereotypy refers to coordinated movements that repeat continually and identically. However, there may be long periods of minutes between movements, or the movements may be very frequent. When they occur at irregular intervals, stereotypies may not always be easily distinguished from motor tics, compulsions, gestures, and mannerisms. They can also appear as paroxysmal movements when a child is excited (Tan et al., 1997). In their classic monograph on tics, Meige and Feindel (1907) distinguished between stereotypies and motor tics by describing the latter as acts that are impelling but not impossible to resist, whereas the former, while illogical, are without an irresistible urge. Tics almost always occur intermittently and not continuously – that is, they occur paroxysmally out of a background of normal motor behavior. Although stereotypies can also be bursts of repetitive movements emerging out of a background of normal motor activity, they often repeat themselves in a uniform repetitive fashion for long periods of time (Lees, 1985). Stereotypies typically occur in patients with tardive dyskinesia (Video 1.73) and with schizophrenia, intellectual disability (especially Rett syndrome) (Video 1.74), and autism (Video 1.75), characteristics that assist in separating these from motor tics (Shapiro et al., 1988). Stereotypies apparently occur in Asperger syndrome, a form of mild autism. They have been seen in patients with the Kluver–Bucy syndrome (Video 1.76). Commonly, they are seen in normal children left alone and when not in contact with other people (Video 1.77). ![]()