Chapter 64 Chronic hepatitis

Epidemiology, clinical features, and management

Chronic Hepatitis

Chronic Hepatitis C

Epidemiology

Hepatitis C is an RNA virus and a member of the family Flaviviridae and affects approximately 1.6% of the American population, with estimates at 3 to 4 million infected (Armstrong, 2006). Most commonly, the disease is transmitted by blood-to-blood to contact. Before the availability of the hepatitis C antibody test in the early 1990s, posttransfusion hepatitis C was a common means of contraction. However, the availability of reliable assays has led to a marked decrease in the incidence of posttransfusion hepatitis C (Alter, 1997). Currently, the risk of posttransfusion hepatitis C is approximately 1 in 2 million transfusions. The much more common means of contracting hepatitis C is by intravenous drug use. Other needle-stick exposures, such as with tattoos and occupational exposure, account for a much lower percentage of cases. Sexual transmission is likewise a low risk, particularly among monogamous partners. However, the prevalence of hepatitis C is much higher at sexually transmitted disease clinics, affecting nearly 10% of nonintravenous drug–using patients (Thomas et al, 1994), presumably related to sexual promiscuity and/or traumatic sex, with increased risk of blood to blood exposure. Inhalation of cocaine has been raised as a potential risk factor, based on the transmission via blood on straws used to snort the inhaled agent (Hepburn & Lawitz, 2004). This risk factor has been questioned, with the issue that inhaled cocaine may be associated with other high-risk behaviors that are, in fact, the modes of transmission.

Presentation

Patients with chronic hepatitis C are frequently asymptomatic, although many have nonspecific symptoms, usually related to fatigue, myalgias, arthralgias, and/or right upper quadrant discomfort. Most patients are only diagnosed when they seek medical care for other reasons or with the above symptoms and are found to have mild elevations of the transaminases. However, up to 30% of patients will have normal transaminases at any one time because transaminase levels may wax and wane over time (Piton et al, 1998). Thus a history of any of the risk factors outlined above should lead to serologic testing to rule out hepatitis C.

Diagnosis

The standard screening study for hepatitis C is an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for antibody to hepatitis C. This is the standard test used by blood banks around the country; it has a sensitivity and specificity in high-risk populations ranging from 98% to 100% (Vrielink et al, 1995). If a patient has a known risk factor and elevated transaminase levels, a positive hepatitis C antibody study by ELISA is consistent with the diagnosis of hepatitis C. The presence of hepatitis viremia is checked with a reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Unfortunately, the PCR may take days to a week to get results, depending on the frequency of testing at the local lab. Patients can have a positive antibody study without viremia if the acute infection spontaneously resolved, an event that occurs 15% to 40% of the time (Herrine, 2002). Antibody positivity frequently persists indefinitely, but it does not imply infection if viremia is absent, based on an undetectable viral load by PCR. Patients will have one of six genotypes, variants in the hepatitis C genome that mainly reflect responsiveness to antiviral therapy (McHutchison et al, 1998). If screening for hepatitis C, and background on a patient being considered for surgery is all that is needed, a genotype need not be checked. However, if antiviral therapy is being considered, a genotype will provide important information regarding the chance of a virologic response and the length of therapy. Genotype 1 is the most common genotype in the United States, accounting for 70% of cases. Genotype 2 accounts for 15% of cases, and genotype 3 accounts for another 10% (McHutchison et al, 1998). Genotype 4 is occasionally seen in the United States, although it is more commonly seen in the Middle East and northern and central Africa. Genotypes 5 and 6 are seen in the United States, although rarely; prevalence of each is higher in South Africa and Southeast Asia, respectively.

Natural History

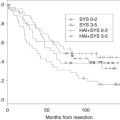

The course of hepatitis C is quite variable and can be influenced by a number of factors. Progression of the disease is routinely measured over decades. One commonly quoted figure is that 20% of those with the disease for at least 20 years will have cirrhosis. It is important to keep in mind that this implies that 80% of those with the disease for 20 years do not have cirrhosis. Another important consideration in determining the extent of the disease at the time of surgical evaluation is knowledge of when the disease was contracted. For example, if the patient knows he or she received a blood transfusion at the time of a motor vehicle accident 35 years ago, the patient has probably had the disease for 35 years. Likewise, a patient with an extensive history of intravenous drug use as a young adult has likely had the disease for several decades by the sixth or seventh decade of life. The disease takes an accelerated course in patients who ingest excessive amounts of alcohol (Wiley et al, 1998), contract the disease at a later age, and are coinfected with HIV or hepatitis B (Ragni & Belle, 2001; Tsai et al, 1996).

Treatment

Hepatitis C treatment is centered around the use of pegylated interferon and ribavirin. Routinely, the patient with chronic hepatitis C is started on therapy for one of several reasons; without question, the presence of hepatitis C viremia is the primary consideration for therapy, but careful consideration is also given to genotype, histologic changes, and potential relative and absolute contraindications. For example, patients with genotype 1 have a 45% to 50% chance of achieving a sustained virologic response, or “cure,” if they can complete a course of therapy. However, the profound fatigue and flulike symptoms commonly associated with antiviral therapy often lead to a decision to delay therapy if histologic changes are mild. For example, if a patient has genotype 1 with a high viral load, the most common demographic in American patients, a liver biopsy showing low-grade inflammation and fibrosis often leads to a period of observation that often lasts for years, or until therapeutic breakthroughs occur. If additional comorbidities associated with a poor response are added to this scenario, such as obesity (Charlton et al, 2006) and/or insulin resistance (D’Souza et al, 2005), and the patient is African American (Jeffers et al, 2004), the potential for successful treatment can drop to 20% to 25%, usually leading clinicians to delay therapy until factors that can be modified are changed. In the face of a disease that potentially may not lead to cirrhosis for 20 to 30 years, if ever, the wisdom of such an approach becomes obvious. Genotype 2 and 3 patients, however, respond in the range of 70% to 80% of the time, routinely requiring only 24 weeks of therapy versus the 48 recommended for genotype 1 patients. This higher response rate can be affected by the same cofactors outlined above.

Other potential contraindications to antiviral therapy include uncontrolled psychiatric illness, renal insufficiency, severe cardiopulmonary disease, and alcohol or substance abuse. Pegylated interferon and ribavirin can induce and exacerbate depression (Renault et al, 1987); thus recent suicidal ideation is an absolute contraindication to therapy. Well-controlled psychiatric disease can be successfully treated with careful follow-up. Renal insufficiency is a relative contraindication because of renal excretion of both interferon and ribavirin (Bino et al, 1982; Glue, 1999). The ribavirin dose must be decreased to avoid severe hemolytic anemia. Unfortunately, strict guidelines are not available, so dosing is often started at a low level, then increased based on patient tolerance. The anemia induced by ribavirin can exacerbate cardiac and pulmonary disease; these patients must therefore be carefully assessed before starting therapy. For example, a patient with congestive heart failure and a left ventricular ejection fraction of 40% may decompensate in the face of a drop in hemoglobin from 14 to 7 g/dL. Finally, patients with a history of alcohol or substance abuse are usually not treated until a period of abstinence can be maintained. Studies have shown a decreased response rate in patients with ongoing alcohol abuse (Pessione et al, 1998). Whether alcohol has a direct effect on drug pharmacokinetics and/or efficacy is unclear; however, the potential effect on compliance is obvious.

On treatment, laboratory work is followed at least monthly and more often if needed. Thyroid function is assessed quarterly because of the potential for development of hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism (Marcellin et al, 1992). The addition of growth factors for cytopenias is often clinician dependent. Most clinicians start supplemental erythropoietin with a hemoglobin level less than 10 g/dL, although many clinicians start erythropoietin if a patient has severe fatigue in the face of a drop in hemoglobin of 25% to 40% (e.g., from 18 to 11 g/dL). Absolute neutrophil counts less than 500 mm3 usually lead to supplemental filgrastim, although many clinicians start filgrastim in response to an absolute neutrophil count of less than 1000 mm3. Drops in hemoglobin, absolute neutrophil counts, and platelet counts may lead to dose reduction of pegylated interferon and/or ribavirin, although the current standard of care is to attempt to maintain patients on standard doses unless all other measures fail.

Viral loads are monitored at 4, 12, and 24 weeks of therapy (Ghany et al, 2009). An undetectable viral load after 4 weeks of therapy is associated with an 85% to 90% response rate, if the patient can complete the course of therapy, regardless of genotype (Ferenci et al, 2005). Thus a response at 4 weeks should lead to maximal efforts to maintain a patient at standard doses and a full course of therapy. An undetectable viral load observed at 12 weeks drops the rate of a sustained virologic response to 67% to 80% (Davis et al, 2003), whereas patients with a “late” response at week 24 only respond approximately 18% to 30% of the time (Berg et al, 2006; Pearlman et al, 2007). In patients with the first undetectable viral load at 24 weeks, recent studies suggest that extending therapy for an additional 24 weeks may improve the rate of response by 20%, although patient tolerance for this extended therapy is poor (Berg et al, 2006; Pearlman et al, 2007).

If undetectable viremia is achieved during therapy, viral load is routinely checked 3 to 6 months following the end of therapy. An undetectable viral load at that point is consistent with a sustained virologic response. Long-term studies have shown this response is durable, with undetectable viral loads persisting indefinitely (Desmond et al, 2006), unless the patient is reinfected. Patients who do not respond to antiviral therapy do not benefit from another treatment trial unless specific circumstances resulted in underdosing. New classes of medicines are under study, and when used in combination with pegylated interferon and ribavirin, protease inhibitors appear to increase response rates.

Hepatitis B

Epidemiology

Hepatitis B is a DNA virus that represents the number one cause of chronic viral hepatitis worldwide, with more than 2 billion people infected at some point and more than 350 million infected chronically (World Health Organization, 2008). More than 45% of the world’s population lives in endemic areas, particularly in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa (Mahoney, 1999). More than 8% of the population in these areas is positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). The prevalence is much lower in North America, affecting less than 2% of the population overall. In the United States, approximately 73,000 new cases occur each year, with approximately 1.25 million patients infected chronically (McQuillan et al, 1999). However, because of the mobility of the world’s population, the possibility of acute or chronic hepatitis B must be considered in patients who have come to the United States. These changes in patterns of immigration will likely increase the prevalence of the disease by as much as a factor of two.

Transmission

In the United States, the most common means of transmission is via percutaneous or permucosal exposure to blood or body fluids (Gust, 1996); thus sexual transmission and parenteral exposure via needle sticks account for the majority of cases. Vertical transmission is relatively rare in this country because of the identification of HBsAg-positive mothers and the administration of hepatitis B immune globulin and the hepatitis B vaccine at the time of birth. Failure to administer these agents frequently leads to chronic infection in the neonate because of the inability of an immature immune system to eradicate hepatitis B virus (Lok, 2002).

Natural History

Acute hepatitis B resolves spontaneously in 90% of patients. The other 10% with persistent HBsAg require careful assessment and follow-up. Within the past decade, the natural history of chronic hepatitis B has been rewritten. Previously, patients either were “chronic carriers” or had “chronic hepatitis B,” which is now defined more as a spectrum of disease that slowly evolves from one phase to another. Patients who contract hepatitis B in the perinatal period frequently maintain high levels of hepatitis B viremia with normal transaminases (Lok & Lai, 1988), which may persist for decades. This “immune tolerant” phase is characterized by the absence of liver injury, or at most only minimal injury.

Current guidelines recommend observation with regular follow-up of liver biochemistry panels, hepatitis B serology, and viral load. Spontaneous HBeAg to HBeAb seroconversion occurs at a rate of 8% to 12% of patients per year (Hoofnagle et al, 1981). An exacerbation of hepatitis B may accompany seroconversion, with marked elevations of the transaminases. Many of these patients (67% to 80%) enter the inactive carrier state, with absent or low-level viral replication, normal transaminases, and minimal histologic damage (Hoofnagle et al, 1981). However, 10% to 30% of HBeAb-positive patients continue to have elevated transaminases, viral replication, and histologic damage (Davis et al, 1984). Up to 20% of HBeAb-positive patients may revert back to an HBeAg-positive phase, with elevated viral loads and transaminases (Davis et al, 1984).

Treatment

Patients with acute hepatitis B are treated supportively. Because 90% of cases resolve spontaneously, antiviral therapy is not indicated, and two studies have shown no benefit to the use of lamivudine (Kumar et al, 2007; Tassopoulus et al, 1997). Cases of chronic hepatitis B must be carefully assessed to determine the appropriate treatment for the patient, and guidelines have been published by several professional societies. The key themes throughout all of the published guidelines include certain principles: 1) if transaminase levels are normal, observe, even if there is a detectable viral load; 2) consider treatment if transaminase levels are elevated or if significant histologic damage is evident; and 3) consider treatment in all patients with cirrhosis who have chronic hepatitis B.

Medical management is centered around the use of nucleoside/nucleotide analogues or pegylated interferon. The nucleoside/nucleotide analogues are relatively nontoxic and easy to take, although years of treatment may be necessary before seroconversion occurs. Entecavir, tenofovir, and telbivudine are potent suppressants of hepatitis B viral replication, although telbivudine is associated with a high rate of hepatitis B viral resistance (Lok & McMahon, 2009). Lamivudine, the mainstay of therapy for over a decade, is not considered first-line therapy because of high levels of drug resistance. Pegylated interferon offers a defined treatment length of 48 weeks; however, weekly subcutaneous injections and significant side effects make it less attractive to many. The nucleoside/nucleotide analogues lead to eradication of viral replication in approximately 80% of patients, with HBeAg seroconversion in up to 22%; pegylated interferon leads to HBeAg seroconversion in up to 34% (Lok & McMahon, 2009).

Surgery in the Patient with Chronic Hepatitis B

No special precautions are necessary in patients with chronic hepatitis B unless a patient has cirrhosis. Otherwise, surgery can proceed as scheduled. If the patient is undergoing antiviral therapy, discontinuation of the antiviral agent can lead to replicative rebound, resulting in acute hepatitis and potential liver failure. Thus antiviral agents should not be suddenly stopped until the situation can be discussed with a hepatologist. Any HBsAg-positive patient not taking an antiviral agent should be considered for prophylactic antiviral therapy if immunosuppressive therapy or chemotherapy is started (Lok & McMahon, 2009). Flares of hepatitis, even to the point of hepatic decompensation and death, have been reported in patients without evidence of viral replication (Yeo & Johnson, 2006).

Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis

Epidemiology

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is slowly becoming the most common liver disease worldwide. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has a prevalence of 3% to 23% of the North American population (Clark et al, 2002; McCullough, 2005). The prevalence of fatty liver disease has paralleled the increase in body weight seen globally. Nearly 75% of those with obesity or type 2 diabetes mellitus have NAFLD (McCullough, 2005), and approximately 20% of obese subjects have NASH (Wanless & Lentz, 1990). The increase in body mass seen in the United States over the last 25 years suggests the prevalence will rise before it falls.

Presentation

Patients are usually without symptoms. During routine physical examinations and health screenings, abnormal transaminase levels are a frequent problem. Right upper abdominal quadrant fullness or pain is a common symptom, and patients routinely have multiple features of metabolic syndrome, including hyperlipidemia, hyperglycemia/diabetes mellitus, and hypertension. All these issues appear to be related to the development of insulin resistance (Grundy et al, 2004).

Diagnosis

Fatty infiltration of the liver is only detected if more than 30% of the parenchyma is infiltrated with fat (Saadeh et al, 2002). If fat is detected, a liver biopsy is not absolutely required. Many hepatologists proceed with biopsy if there is any suspicion of another liver disease, such as borderline autoimmune serologies or mildly elevated iron studies, or if there is some question as to the presence of moderate to severe fibrosis. The biopsy can be used to rule out other liver diseases and as a means of staging the amount of fibrotic tissue. The latter is seen as an incentive to patients to begin a dedicated weight loss program. Biopsies from patients with NASH show fat and inflammation, although distinguishing the findings from alcoholic steatohepatitis may be difficult.

Natural History

Hepatic steatosis occurs with minimal or no inflammatory changes histologically, but NASH is associated with necroinflammatory changes; both may progress to fibrosis and cirrhosis. Natural history studies are relatively few in number, because of small patient numbers and limited long-term follow-up. However, NASH progresses to cirrhosis in 15% to 20% of patients (Edmison & McCullough, 2007). Progression is obviously shorter in patients presenting with advanced fibrosis, although 30% of patients will have progression of fibrosis over 5 years (Fassio et al, 2004).

Treatment

In spite of multiple trials of medical treatments, the mainstay of therapy for NASH remains weight loss (Hickman et al, 2004). Decreased dietary intake, ideally complemented by an exercise program, will lead to weight loss, a decrease in hepatic fat, and lower transaminase levels. Weight loss in the amount of 10% to 15% of the current body weight over the course of a year is a reasonable and attainable goal for most patients. However, bariatric surgery and its frequent accelerated weight loss is not harmful and has been associated with histologic improvement (Kral et al, 2004).

Medical therapy for NASH has been the subject of multiple drug trials. Thiazolidinediones have been associated with improvement of transaminase levels and a decrease in histologic fat (Aithal et al, 2008). However, weight gain is a potential side effect; thus use of this class of medications solely to improve NASH is not standard practice. If a patient is diabetic and has NASH, pioglitazone or rosiglitazone may be considered. Agents such as vitamin E, betaine, metformin, and pentoxifylline have also been used in small trials without remarkable improvement. Thus weight loss remains the foundation of NASH treatment.

Surgery in the Patient with Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis

Routinely, no special precautions need be taken for the operative candidate with NASH in the absence of cirrhosis. However, large hepatic resections in patients with fatty livers have been associated with decompensated liver disease postoperatively (Kooby et al, 2003; Parikh et al, 2003). Thus careful assessment of the patient being considered for hepatic resection must take all of these factors into account. A liver biopsy may provide the necessary information regarding baseline hepatic histology, the extent of fatty infiltration and fibrosis, and the presence of other lesions that may lead to postoperative decompensation.

Autoimmune Hepatitis

Epidemiology

Autoimmune hepatitis is a chronic, usually progressive liver disease with an incidence among Northern Europeans of 1.9 per 100,000 population (Boberg et al, 1998) and 1 per 200,000 in the United States (Manns et al). Although often characterized as a disease of middle-aged women, all ages can be affected, including the very young and the elderly, but women are affected more often than men. Patients frequently have a coexistent autoimmune disease; a history of thyroid disease, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, or other autoimmune disease should raise the possibility of the diagnosis in a patient who presents with elevated liver biochemistry results (Abdo et al, 2004).

Natural History

Autoimmune hepatitis is often a progressive disease, with death occurring in 40% of untreated patients. In those surviving the initial illness, another 40% progress to cirrhosis with the potential manifestations of end-stage liver disease, including ascites, portal hypertension, and hepatic encephalopathy. Not unexpectedly, severe histologic damage on the initial liver biopsy is a poor prognostic factor. Although transaminase elevations do not always correlate with the degree of liver damage or prognosis in other liver diseases, persistent transaminase elevations greater than 10 times the upper limit of normal are associated with higher early mortality rates. Patients with milder laboratory and histologic findings have a less severe course; however, cirrhosis still develops in 49% of patients over a period of 15 years (Czaja & Freese, 2002). Thus early diagnosis and treatment are key to prolonging long-term survival.

Treatment

Immunosuppressive therapy is the key to controlling this progressive disease. Although treatment protocols vary by center and clinician, corticosteroid-based treatment is most common. A 30- to 60-mg daily dose of oral prednisone is usually started in most cases, even in patients with coexistent diseases that potentially could be affected, such as diabetes mellitus. Because of the adverse effects associated with long-term high-dose corticosteroid therapy, the dose is tapered over varying amounts of time, ranging from weeks to months. Because of the potential for disease flares as the corticosteroid dose is tapered, most patients start azathioprine at a dose of 50 mg daily along with corticosteroids, or azathioprine is started within 2 to 3 months of the initiation of treatment (Czaja & Freese, 2002). Azathioprine is usually not effective for 4 to 8 weeks after initiation; thus many clinicians start it with prednisone rather than delaying. Although 90% of adults show marked improvement in laboratory studies and symptoms within 2 weeks of starting therapy, disease remission is uncommon in less than 12 months. Thus azathioprine is continued after prednisone is tapered off. As the prednisone is tapered, elevations in transaminases can be addressed with an increase in dose; however, the long-term side effects associated with corticosteroids make this a less than ideal choice. Thus doses of azathioprine incrementally increased to a maximum dose of 2 mg/kg/day are routinely used, if the disease flares during the steroid taper.

Depending on the severity of the histologic damage seen initially, most clinicians continue the azathioprine for at least 1 to 2 years. Even with normal transaminase levels, a significant number of patients have ongoing interface hepatitis on immunosuppressive therapy. Thus any attempt to stop immunosuppressive therapy should be preceded by a liver biopsy to assess the histologic response to therapy. As a rule, more severe initial changes will take longer to correct and will lag behind biochemical improvement. Many clinicians see autoimmune hepatitis as a chronic disease that inevitably flares off therapy, although some patients go into remission and can remain off therapy without histologic progression. Patients tapered off therapy should be followed up with liver biochemistry measurements at least twice a year because relapses may occur without symptoms. Reinstitution of immunosuppressive therapy leads to improvement in most patients within 2 years and should lead to indefinite immunosuppressive therapy with azathioprine, and in some cases prednisone, based on liver biochemistries (Czaja & Freese, 2002).

The complications of long-term corticosteroid therapy are well known and need not be outlined. However, the short- and long-term consequences associated with azathioprine are less well known and worth listing. Bone marrow suppression—with anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia—is the most common laboratory abnormality. Symptomatically, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain may lead to cessation of therapy as a result of intolerance. Acute pancreatitis is rare, as is hepatoxicity, typically marked by sinusoidal obstructive syndrome or cholestasis, both of which usually respond to drug cessation. Long-term treatment can result in malignancy, usually a lymphoma or leukemia (Kandiel et al, 2005). However, one series of patients with autoimmune hepatitis followed for more than 20 years showed no incidence of malignancy (Johnson et al, 1995).

Approach to Surgery in Patients with Liver Disease

Partly because of the epidemic of obesity and NAFLD, increasing numbers of patients with chronic liver disease are undergoing nonhepatic and nontransplant operations. Liver disease, especially significant fibrosis or cirrhosis, represents a significant risk factor for perioperative morbidity and mortality. Any clinically evident signs of liver dysfunction should raise concern, particularly for intraabdominal operations. Although no absolute consensus on risk quantification has been reached, the perioperative risk in patients with liver disease clearly increases with the severity of liver dysfunction (Teh et al, 2007). Perioperative risk in these patients can be quantified using the Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) score and/or the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score (Teh et al, 2007; Muilenburg et al, 2009; del Olmo et al, 2003), which can discriminate risks to a finer degree than the CTP score and has evolved as the best predictor of 30- and 90-day operative mortality rate (Teh et al, 2007). Furthermore, perioperative mortality risk greatly increases in patients with MELD scores higher than 10 to 15 (Costa et al, 2009; Morisaki et al, 2010; Northup et al, 2005; Telem et al, 2010; Teh et al, 2007), and there also is utility in MELD-based variants in making more refined predictions regarding surgical risk (Costa et al, 2009; Telem et al, 2010).

Abdo A, Meddings J, Swain M. Liver abnormalities in celiac disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:107-112.

Aithal GP, et al. Randomized, placebo controlled trial of pioglitazone in non-diabetic subjects with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1176-1184.

Alter MJ. Epidemiology of hepatitis C. Hepatology. 1997;26(3 Suppl 1):62S-65S.

Armstrong GL, et al. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1999 through 2002. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:705-714.

Berg T, et al. Extended treatment duration for chronic hepatitis C virus type 1: comparison of 48 versus 72 weeks of peginterferon-alfa-2a plus ribavirin. Gastroenterology. 2006;13:1086-1097.

Bino T, et al. The kidney is the main site of interferon degradation. J Interferon Res. 1982;2:301-308.

Boberg KM, et al. Incidence and prevalence of primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, and autoimmune hepatitis in a Norwegian population. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:99-103.

Charlton MR, Pockros PJ, Harrison SA. Impact of obesity on treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2006;43:1177-1186.

Clark JM, Brancati FL, Diehl AM. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1649-1657.

Costa BP, et al. Value of MELD and MELD-based indices in surgical risk evaluation of cirrhotic patients: retrospective analysis of 190 cases. World J Surg. 2009;33:1711-1719.

Czaja AJ, Freese DK. Diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2002;36:479-497.

Davis GL, Hoofnagle JH, Waggoner JG. Spontaneous reactivation of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Gastroenterology. 1984;86:230-235.

Davis GL, et al. Early virologic response to treatment with peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:645-652.

del Olmo JA, et al. Risk factors for nonhepatic surgery in patients with cirrhosis. World J Surg. 2003;27:647-652.

Desmond CP, et al. Sustained virological response rates and durability of the response to interferon-based treatment in hepatitis C patients treated in the clinical setting. J Viral Hepat. 2006;13:311-315.

D’Souza R, Sabin CA, Foster GR. Insulin resistance plays a significant role in liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C and in the response to antiviral therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1509-1515.

Edmison J, McCullough AJ. Pathogenesis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: human data. Clin Liver Dis. 2007;11:75-104.

Fassio E, et al. Natural history of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: a longitudinal study of repeat liver biopsies. Hepatology. 2004;40:820-826.

Ferenci P, et al. Predicting sustained virological responses in chronic hepatitis C patients treated with peginterferon (40 kd)/ribavirin. J Hepatol. 2005;43:425-433.

Ghany MG, et al. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: an update. Hepatology. 2009;49:1335-1374.

Glue P. The clinical pharmacology of ribavirin. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19(Suppl 1):17-24.

Grundy SM, et al. Definition of metabolic syndrome: report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association Conference on Scientific Issues Related to Definition. Circulation. 2004;109:433-438.

Gust ID. Epidemiology of hepatitis B infection in the Western Pacific and South East Asia. Gut. 1996;38(Suppl 2):S18-S23.

Hepburn MJ, Lawitz EJ. Seroprevalence of hepatitis C and associated risk factors among an urban population in Haiti. BMC Gastroenterology. 2004;4:31.

Herrine SK. Approach to the patient with chronic hepatitis C infection. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:747-757.

Hickman IJ, et al. Modest weight loss and physical activity in overweight patients with chronic liver disease results in sustained improvements in alanine aminotransferase, fasting insulin, and quality of life. Gut. 2004;53:413-419.

Hoofnagle JH, et al. Seroconversion from hepatitis B e antigen to antibody in chronic type B hepatitis. Ann Intern Med. 1981;94:744-748.

Jeffers LJ, et al. Peg-interferon alfa-2a (40 kd) and ribavirin for black American patients with chronic HCV genotype 1. Hepatology. 2004;39:1702-1708.

Johnson PJ, McFarlane IG, Williams R. Azathioprine for long-term maintenance of remission for autoimmune hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:958-963.

Kandiel A, et al. Increased risk of lymphoma among inflammatory bowel disease patients treated with azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine. Gut. 2005;54:1121-1125.

Kooby DA, et al. Impact of steatosis on perioperative outcome following hepatic resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:1034-1044.

Kral JG, et al. Effects of surgical treatment of the metabolic syndrome on liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. Surgery. 2004;135:48-58.

Kumar M, Satapathy S, Monga R. A randomized controlled trial of lamivudine to treat acute hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2007;45:97-101.

Lok AS. Chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1682-1683.

Lok AS, Lai CL. A longitudinal follow-up of asymptomatic hepatitis B surface antigen-positive Chinese children. Hepatology. 1988;8:1130-1133.

Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:1-36.

Mahoney FJ. Update on diagnosis, management, and prevention of hepatitis B virus infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:351-366.

Manns MP, Luttig B, Obermayer-Straub P: The autoimmune diseases. In Rose NR, MacKay IR (eds): Autoimmune Hepatitis, 3rd ed. New York, Academic Press, pp 511–525.

Marcellin P, et al. Sustained hypothyroidism induced by recombinant alpha interferon in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gut. 1992;33:855-856.

McCullough AJ. The epidemiology and risk factors of NASH. In: Farrell, GC, et al. Fatty Liver Disease: NASH and Related Disorders. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Publishing; 2005:23-37.

McHutchison JG, et al. Interferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1485-1492.

McQuillan GM, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B infection in the United States: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 1976 through 1994. Am J Pub Health. 1999;89:14-18.

Morisaki A, et al. Risk factor analysis in patients with liver cirrhosis undergoing cardiovascular operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:811-817.

Muilenburg DJ, et al. Surgery in the patient with liver disease. Med ClinNorth Am. 2009;93:1065-1081.

Northup PG, et al. Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) predicts nontransplant surgical mortality in patients with cirrhosis. Ann Surg. 2005;242:244-251.

Parikh AA, et al. Perioperative complications in patients undergoing major liver resection with or without neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:1082-1088.

Pearlman B, Ehleban C, Saifee S. Treatment extension to 72 weeks of peginterferon alfa-2b and ribavirin in hepatitis C genotype 1–infected slow responders. Hepatology. 2007;46:1688-1694.

Pessione F, et al. Effect of alcohol consumption on serum hepatitis C virus RNA and histologic lesions in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 1998;27:1717-1722.

Piton A, et al. Factors associated with serum alanine transaminase activity in healthy subjects: consequences for the definition of normal values, for selection of blood donors and for patients with chronic hepatitis C. MULTIVIRC Group. Hepatology. 1998;27:1213-1219.

Ragni MV, Belle SH. Impact of human immunodeficiency virus on progression to end-stage liver disease in individuals with hemophilia and hepatitis C virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:1112-1115.

Renault PF, et al. Psychiatric complications of long-term interferon-alfa therapy. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:1577-1580.

Saadeh S, et al. The utility of radiologic imaging in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:745-750.

Tassopoulus MC, et al. Recombinant interferon-alfa therapy for acute hepatitis B: a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Viral Hepat. 1997;4:387-394.

Telem DA, et al. Factors that predict outcome of abdominal operations in patients with advanced cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(5):451-457.

Teh SH, et al. Risk factors for mortality after surgery in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1261-1269.

Thomas DL, et al. Hepatitis C, hepatitis B, and human immunodeficiency virus infections among non-intravenous drug-using patients attending clinics for sexually transmitted diseases. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:990-995.

Tsai JF, et al. Independent and additive effect modification of hepatitis B and C virus infection on the development of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1996;24:271-276.

Vrielink H, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of three third-generation anti-hepatitis C virus ELISAs. Vox Sang. 1995;69:14-17.

Wanless IR, Lentz JS. Fatty liver hepatitis (steatohepatitis) and obesity: an autopsy study with analysis of risk factors. Hepatology. 1990;12:1106-1110.

Wiley TE, et al. Impact of alcohol on the histological and clinical progression of hepatitis C infection. Hepatology. 1998;28:805-809.

World Health Organization. Hepatitis B. World Health Organization Fact Sheet 204 (Revised August 2008). Available at http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en/index.html, 2008.

Yeo W, Johnson PJ. Diagnosis, prevention and management of hepatitis B virus reactivation during anticancer therapy. Hepatology. 2006;43:209-220.